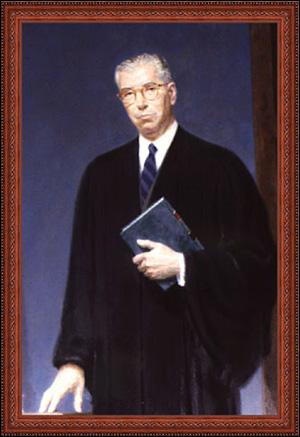

During his unsurpassed twenty-seven years and eight months as a member of the Court of Appeals-seven years of that as Chief Judge-Stanley Fuld exhibited a determined yet humble dedication to pursuing justice, preserving common law traditions and serving the people of New York State. A prolific jurisprudential craftsman, Fuld painstakingly produced classically reasoned opinions that cautiously advanced the common law to accommodate modern sensibilities; he labored exhaustively to minimize the logical gap between precedent and novel applications of the law. In recognition of Fuld’s common law artistry, he is-and even was throughout his career-regularly compared to Benjamin Cardozo, the early twentieth century common law luminary whose former chambers he occupied in New York City and in Albany.

Justice and Reform

Judge Fuld’s career reflected a focused commitment to justice and an unyielding reverence for the law. Stanley Howells Fuld was born in New York City on August 23, 1903. His father was a linotyper and later a proofreader for The New York Times; his mother died of pneumonia when he was twelve. After being educated in New York City public schools, Fuld attended the City College of New York, from which he was graduated cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa. He studied law at Columbia Law School, where he served as an editor of the Columbia Law Review and was elected to the Order of the Coif. Following his admission to the New York Bar, Fuld entered private practice. He initially worked at Gilman & Unger, a New York City firm with three partners and two associates, and later moved to another small firm, Aranow & Berlack, where he was invited to partnership.

In 1935, with the encouragement of his friend and law school classmate Professor Milton Handler, Fuld transitioned into public service, accepting a position with the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which was designed to be a cornerstone of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. Some three months after Fuld joined the NRA, its existence was called into doubt by Schecter Poultry Corp. v. United States (295 US 495 [1935]), a decision in which the Supreme Court invalidated the compulsory code system that the NRA administered. Realizing that his future did not lie with the NRA, Fuld wrote to Thomas E. Dewey, a law school contemporary whom Governor Herbert H. Lehman had recently named as Special Prosecutor to investigate organized crime in New York County. Dewey was authorized to enlist a staff of twenty, and he made Fuld one of his first appointments in the Office of the Special Prosecutor. Fuld quickly became Dewey’s “law man,” handling and arguing scores of appeals and participating in the preparation of innumerable motions and briefs. Fuld undertook the herculean project of streamlining the research operation of the office, conceiving of and implementing an exhaustive in-house treatise that catalogued and cross-referenced every criminal law decision of the New York Court of Appeals from 1847 to date. He also wrote or oversaw the creation of over 500 legal memoranda that he comprehensively indexed in order to help the office avoid duplicative research.

Fuld assisted in the drafting of legislation that allowed for multicount indictments. Traditionally, each indictment could only charge one offense. However, the Special Prosecutor sought the power to bring multicount indictments in order to try racketeers together with the henchmen who carried out the racketeers’ orders. Common trials for organized crime commanders and soldiers would enable juries to understand how the racketeers managed criminal enterprises from behind the scenes. The legislation that Fuld helped draft became law in 1936, and it facilitated the prosecution of high-ranking organized crime figures.

In 1937, Dewey was elected District Attorney of New York County, and he named Fuld as his Chief of the Indictment Bureau. In that capacity, Fuld reformed indictments by writing them in simple, straightforward language, instead of the archaic, convoluted terms that had been the accepted norm. The Harvard Law Review hailed Fuld’s reform as “a significant step towards a more rational criminal procedure.”1 In 1939, Fuld became the Chief of the Appeals Bureau, a position that afforded him the opportunity to argue hundreds of appeals in the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals.

At the District Attorney’s Office, Fuld persisted in his dedication to legal reform. He fashioned the concept of “continuing larceny,” a doctrine that enabled a series of closely connected petit thefts to be aggregated for prosecution as grand larceny. The Court of Appeals upheld the application of the continuing larceny doctrine in People v. Cox (286 N.Y. 137 [1941]). In 1942, Fuld continued his efforts to modernize the law of larceny in New York by drafting a statute that abolished the antiquated distinctions between variations of larceny-such as larceny by trick, false pretenses, and ordinary larceny. Following the enactment of Fuld’s statute, guilty thieves no longer were set free merely because prosecutors had unwittingly charged them pursuant to technically inapposite forms of larceny.

Although Fuld was a zealous advocate for the State in his capacity as an Assistant District Attorney, he perennially exhibited a paramount commitment to fairness and justice. As the Chief of the Appeals Bureau, he would urge reversal of a conviction when he felt that error had tainted it. He also championed the revival of the writ of error coram nobis, a previously mothballed mechanism for correcting injustice by allowing a court to reconsider a conviction in light of facts that had subsequently emerged. As Fuld explained in a heralded New York Law Journal essay, the writ provided an “emergency measure enabling a defendant to avoid the effects of a conviction procured by fraud or in violation of his constitutional rights when all other avenues of judicial relief are closed to him.”2

A Judicial Legend

In 1944, Fuld left the District Attorney’s Office to return to private practice as a partner in what became known as Hartman, Craven & Fuld. The other principles of the firm, Sigfried Hartman-Fuld’s cousin-and Alex Craven-Fuld’s longtime friend-had extensive experience as trial attorneys and advisors to corporate clients. Fuld simultaneously practiced at the firm and served as a Special Assistant Attorney General. These pursuits ended when Dewey, who had been elected governor in 1941, named Fuld to the Court of Appeals on April 25, 1946. Fuld was selected to fill the remainder of the term of Judge George Z. Medalie, who had died. At 42, Fuld was at that time the youngest person ever appointed or elected to the Court of Appeals. He was elected to a full term later in 1946 and then again in 1960. In 1966, he was elected Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals and Chief Judge of the State of New York, positions he held until his retirement at the end of 1973.

During Fuld’s lengthy tenure on the Court, he had a breathtaking impact on the development of the law. Some 15,000 cases were decided, and Fuld wrote more than 1,300 opinions. Although it is impossible to set forth a comprehensive catalog of those opinions, a handful of illustrative examples that follows provides a flavor-although hardly a sense of the depth and breadth-of Fuld’s impact on contemporary jurisprudence.

In choice of law, Fuld authored leading decisions, such as Auten v. Auten (308 NY 155 [1954]), Babcock v. Jackson (12 NY2d 473 [1963]) and Neumeier v. Kuehner (31 NY2d 121 [1972]), that dispensed with rigid rules relating to what law courts must apply in particular disputes. Fuld’s meticulous opinions led a revolution in choice of law, shifting the focus from formalistic preoccupation with the place of injury or the place of contract to a flexible, practical analysis of the interests of different jurisdictions in applying their laws to particular disputes.

Fuld’s labor law jurisprudence demonstrated a commitment to shielding employees from overreaching by employers (see e.g. Int’l Assoc. of Machinists, Dist No. 15, Local No. 402 v. Cutler-Hammer, Inc., 297 NY 519 [1947, Fuld J., dissenting]), while holding unions accountable for remaining open and democratic (see e.g. Phalen v. Theatrical Protective Union No. 1, 22 NY2d 34 [1968, Fuld, C.J., concurring]); Madden v. Atkins, 4 NY2d 283 [1958]). Fuld maintained the Taylor Law (N.Y. Civ. Serv. L. ” 200-12), which prohibited strikes by public employees, against constitutional challenge on the grounds that the mitigation of market forces in the public sector and important policy concerns justified the regulation (see City of New York v. DeLury, 273 NY2d 175 [1968]). Several of Judge Fuld’s most influential labor law opinions were dissents that presaged United States Supreme Court majority opinions.3

Fuld also left an enduring imprint on the law of corporations. As exhibited in his celebrated opinions in cases such as Walkovszky v. Carlton (18 NY2d 414 [1966]), which preserved the integrity of the corporate veil despite a taxicab company’s failure to carry adequate insurance, and Diamond v. Oreamuno (24 NY2d 494 [1969]), which safeguarded the ability of shareholders to act as private attorneys general against directors and officers who misuse inside information, Fuld’s approach to the law of corporations tended to balance regulatory and permissive instincts. When the New York Legislature enacted the Business Corporation Law (BCL) in 1961, it espoused a similarly balanced approach. The BCL effectively overruled a number of Court of Appeals decisions. Fuld had dissented in most of those cases, and the reasoning of several of his dissents was adopted by the drafters of the BCL.4

Fuld’s contributions to criminal law are renowned. In People v. Donovan (13 NY2d 148 [1963]), he wrote an opinion for the Court holding inadmissible the confession of a suspect whose attorney had requested access to him and been denied. Well before the U.S. Supreme Court decided Miranda v. Arizona (384 US 436 [1966]), Donovan demonstrated substantial sensitivity to the dangers of custodial interrogation in the absence of counsel. Fuld’s lifelong commitment to the fair rule of law, regardless of the characteristics of the beneficiary in any given circumstance, shined in the opinion. He wrote:

The worst criminal, the most culpable individual, is as much entitled to the benefit of the rule of law as the most blameless member of society. To disregard violation of the rule because there is proof in the record to persuade us of a defendant’s guilt would but lead to erosion of the rule and endanger the rights of even those who are innocent (Donovan, 13 NY2d at 154).

In People v. Rosario (9 NY2d 286 [1961]), Fuld’s opinion for the Court expanded the scope of materials that prosecutors are obligated to provide to criminal defendants. He explained that “a right sense of justice entitles the defense to examine a witness’ prior statement, whether or not it varies from his testimony on the stand”(Rosario, 9 NY2d at 289).

In other criminal matters, Fuld failed to carry the Court, but wrote dissents that were ultimately vindicated by the U.S. Supreme Court. In In re Winship (397 US 358 [1970]), the Supreme Court reversed the New York Court of Appeals’ majority opinion in W. v. Family Court (24 NY2d 196 [1969]), and accepted Fuld’s dissenting position that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution requires that adjudications of juvenile delinquency be founded on proof beyond a reasonable doubt. In O’Brien v. Skinner (414 US 524 [1974]), the Supreme Court endorsed Fuld’s dissenting view that New York’s failure to provide pretrial detainees with a means of registering and voting was a denial of equal protection of the laws.

In the area of the First Amendment, Fuld set forth a new method of measuring obscenity in People v. Richmond County News, Inc. (9 NY2d 578 [1961])-the “hard-core pornography” test-that gave wide protection to the public’s ability to choose what it wanted to read and see. That decision was viewed as a breakthrough by scholars and commentators and was acknowledged by the U.S. Supreme Court (see Mishkin v. State of N.Y., 383 US 502, 506-08 & n.4 [1966]; Manual Enters., Inc. v. Day, 370 US 478, 489 [1962]). In Oliver v. Postel (30 NY2d 171 [1972]), Fuld offered a ringing defense of the right of reporters to comment on public trials, a ruling that endeared him to the press despite his general unwillingness to speak with reporters.

Fuld’s dissent championing the protection of civil rights in Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corp. (299 NY 512 [1949]) is widely credited with anticipating the tectonic Brown v. Board of Education (347 US 483 [1954]). Fuld decried distinctions between citizens on the basis of ancestry and explained that “[t]he mandate that there be equal protection of the laws, designed as a basic safeguard for all, binds us . . . to put an end to this discrimination”(Dorsey, 299 NY at 545).

Of course, the smattering of opinions discussed above fails to elucidate the scope or intensity of the impact that Fuld had on the law. Nevertheless, even a sample of Fuld opinions evinces his dedication to securing and reinvigorating legal traditions by infusing them with contemporary pragmatism.

A Labor of Love

None of Stanley Fuld’s opinions came easily to him. Tirelessly, he toiled to arrive at final versions, conscientiously uncovering every layer of the case before him. He knew that the correct decision, the fitting turn of phrase, the appropriate means of cabining a holding and the most effective way to make a point come alive and be memorable all came with hard work and patience. He understood that these fine details could not be shaped in the first draft, or even necessarily the fifth or the tenth. Ultimately, however, a score of drafts later, the layers were laid bare and the path became clear. As Mark Twain said, the “difference between the almost right word and the right word” is the “difference between the lightning-bug and the lightning” (Twain, The Art of Authorship, at 87-88 [George Bainton ed., New York, D. Appleton & Co. 1890]). Fuld bottled lightning and applied it to the printed page decision after decision, year after year, decade after decade.

By the time Fuld had finished working on a draft opinion, it was a virtually indecipherable maze of cross-outs, arrows moving paragraphs around, and inserts all methodically labeled alphabetically from “A” through to double letters. Fuld even continued the editing process after he received the page proofs of opinions from the New York State Reporter, often changing phrases or words. Once an opinion hit the bound volumes, however, Fuld had no regrets. He looked forward and never backward.

Fuld’s perfectionism required his clerks to invest considerable sweat equity in drafting each opinion. As compensation for their efforts, the clerks gained priceless experience. They learned how to modernize the law using traditional means, developing the law one case at a time. Many Fuld clerks went on to build distinguished careers-as leaders of the bar, academics, and judges-that were constructed on the training received as apprentices to the master craftsman.

A Humble Giant

For all the attention Judge Fuld’s decisions received, he remained an intensely private and humble man. He eschewed public speaking engagements and preferred to communicate to the public through his opinions. Although he was rightfully proud of being the Chief Judge of the State of New York and enjoyed the deference due that office in the courtroom, he nonetheless forewent its trappings in public. As but one example, he never availed himself of the state car and driver to which his position entitled him. Instead, he would travel back and forth between New York City and Albany by Greyhound or Trailways bus, often absorbed in exchanging drafts with his clerks along the way.

Fuld knew beyond peradventure that public servants are surrogates for the people, and he carried himself accordingly. At oral argument, his questions were replete with purpose. Lawyers appearing before Fuld knew that his inquiries were not designed to trap the unwary or score debating points, but rather to help the judge better understand the issues needing resolution.

In his quotidian human interactions, Fuld proved as well attuned to the human condition as he did in his opinions. He was deferential, calm, quiet, and courteous. He always had a kind word to put people at ease. His humor was never barbed; usually it manifested itself in the form of harmless, never acerbic, dry puns.

History will remember Stanley H. Fuld as a consummate jurist on a court of seven equals, all strong-minded, intelligent, at that time, men. As Chief Judge, Fuld had to be a conciliator, a moderator of opposing views, an ameliorator of conflicts, and an advocate for his own position. He was all of that and more. In conference, he often managed deftly to convince his colleagues of the correctness of his point of view, while addressing their concerns and incorporating them into his opinions. For all his humility and gentleness, he was highly competitive in conference and always hoped to avoid feeling compelled to write in dissent. His first choice was to carry the court and lead the majority, his second was to be a part of it, and only as a last resort would he dissent. Yet he declined to join the majority when he believed that it was adopting the wrong approach.

Just as Fuld refused to follow the majority blindly, he similarly refused to adhere to precedent that led to fundamental injustice. As he noted in Bing v. Thunig (2 NY2d 656, 667 [1957]), if “adherence to precedent offers not justice but unfairness, not certainty but doubt and confusion, it loses its right to survive and no principle constrains us to follow it.” In those rare instances when Fuld believed that precedent lost its right to survive, he would rigorously ground his departure from it in law and logic.

A Civic Leader and a Family Man

Fuld complemented his professional and personal lives with an abundance of civic involvement. For example, he was Chairman of the Board of Visitors of City College of New York, Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities. He also sat on the boards of Beth Israel Hospital, Central Synagogue, Columbia Law School, the Columbia Law Review Association, Phi Beta Kappa Associates, Cardozo Law School and the Alumni Association of the City College of New York. In addition, he was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and taught at New York University Law School and the Salzburg Seminar in American Studies. He played a central role in organizing the Fair Trial-Free Press Conference, which joined journalists, law enforcement officials, judges, and lawyers in the pursuit of balancing the constitutional rights to a free press and to fair trials. He later served as Chairman of the National News Council, which had a similar mission to the Fair Trial-Free Press Conference.

Fuld was regularly honored with awards for his professional and charitable work. For example, he was the first recipient of the eponymous Stanley H. Fuld Award from the New York State Bar Association for his contributions to commercial litigation. Fuld also received honorary degrees from various institutions, including Columbia University, New York University, Syracuse University, Union College, Hamilton College, The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, Yeshiva University, St. John’s University, and the City College of New York.

Despite Fuld’s many achievements as a lawyer, a judge, and a civic leader, he was most proud of his family. Visitors to Fuld’s chambers were not directed to view the judge’s many awards, but rather a particular photograph of the judge on the Court of Appeals bench with a grandchild sitting in each of the other judge’s chairs. He took tremendous, loving pride in his daughters, Judy and Hermine, and their families. He was married to his first wife Florence for 45 years. Following her death in 1975, he married Stella Rapaport with whom he shared the remaining 28 years of his life.

Return to Private Life

As the New York Constitution requires, Fuld left the bench on the last day of the year in which he turned 70, December 31, 1973. He joined Kaye, Scholer, Fierman, Hayes & Handler as Special Counsel. The firm accepted Fuld’s decision to refrain permanently from appearing before any New York State tribunal. Fuld felt it would be unseemly to do so after having served as the State’s Chief Judge.

Even after returning to private practice, Fuld still sought opportunities to serve the public. For instance, by appointment of President Gerald Ford, Fuld was Chairman of the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyrighted Works from 1975 until 1978. In 1980, he joined the New York State Court Facilities Task Force and two years later, in 1982, the New York City Charter Revision Commission.

The Fuldian Ethic

As one of the finest common law judges of the 20th century, Fuld felt most at ease working within the confines of specific disputes between particular litigants. He was not comfortable making broad generalizations or developing sweeping theories of how to decide cases. Rather, he was at home reviewing the record before him, content to have the general principles arise from an unerringly accurate analysis of the facts and a conscientious application of the law to the issues at hand.

Occasionally, Fuld applied his brush not to a unique set of facts, but to a broader canvas. When he did, the results enlighten with elegance, even decades later. Here are Fuld’s thoughts regarding the administration of the courts on the occasion of his retirement from the Court of Appeals:

Apart, however, from the task of keeping the law abreast of the times, the courts, of course, have an urgent responsibility to see to it that the judicial system itself is continually strengthened and streamlined so as to enable it to function with greater efficiency and dispatch, the better to meet the heavy demands made upon it by burgeoning case loads. At the same time, however, the courts must insure that the ideal of equal protection under law shall be more than a hallowed phrase; that the disadvantaged shall not be denied their rights because of lack of adequate representation; and that the aid and protection of the courts shall ever be available on equal terms to one and all, to the poor, the weak and the unpopular as well as to the rich, the strong and the popular, to the nonconformist as well as to the conformist, and to the bigot as well as to the victim of prejudice. In short, in adjusting the machinery of the court system to achieve greater efficiency of operation, the courts must see to it that the quality of adjudication is not sacrificed to speed of disposition (Remarks at Ceremony Marking Retirement of Chief Judge Stanley H. Fuld and Judge Adrian P. Burke at Albany, New York, 33 NY2d ix, xii-xiii [1973]).

Judge Fuld died on July 22, 2003. He committed his 99-year life to the principles of justice, fairness, and equality, and dedicated over a quarter of a century to the New York Court of Appeals. He assiduously applied reason and decency to the record before him, perennially striving to honor tradition by helping it survive in the modern world. His energy and intellectual curiosity are reflected in a body of work that astonishes in its range, its depth and its persistent significance.

Progeny

Judge Fuld and his first wife Florence had two daughters, Hermine (Mrs. Maurice N. Nessen) of New York City and Judy (Mrs. Frank Miller). Judge Fuld is survived by his second wife Stella, his daughter Hermine, six grandchildren, and seven great-grandchildren. The grandchildren are Joshua Fuld Nessen of New York City; Elizabeth Nessen of Brookline, Massachusetts; William Arthur Nessen of Kuala Lampur, Malaysia; Steven Alan Miller of Los Angeles, California; Peter Miller of Orlando, Florida; and Leah Jessica Matuson of Medfield, Massachusetts.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Burke, Chief Judge Stanley H. Fuld, 71 Colum L Rev 542 (1971).

de Capriles, Judge Fuld’s Opinions on the Law of Business Corporations, 71 Colum L Rev 588 (1971).

Court of Appeals Marks Fuld, Burke Departures, NYLJ, January 12, 1974, at 1.

Cohen, Saying “Excelsior” to Stanley H. Fuld, 104 Colum L Rev 265 (2004).

Dannett, Chief Judge Fuld’s Contribution in the Labor Law Field, 71 Colum L Rev 567 (1971).

Dewey, The Making of a Judge, 71 Colum L Rev 537 (1971).

Douglas, Chief Judge Stanley H. Fuld, 71 Colum L Rev 531 (1971).

Feinberg, Judge Fuld and the Genius of Humility, NYLJ, Dec. 21, 1973, at 1, col 3.

Feinberg, New York’s Court of Appeals and Stanley H. Fuld: An Appreciation, 48 Syracuse L Rev 1477 (1998).

Fuld, Respice (on file with the authors).

Gurfein, Chief Judge Fuld is Seen as Legend in Own Time, NYLJ, Dec. 27, 1973, at 1.

Harlan, Chief Judge Fuld: A Salute from Washington, 71 Colum L Rev 535 (1971).

Judge Stanley Fuld, The KSFH&H Report (Apr., 1974) (on file with the authors).

Kaye, Tribute to Judge Fuld, 104 Colum L Rev 270 (2004).

Krouner, A Memory of Judge Fuld ‘As A Man’, NYLJ Feb. 7, 1974 (photocopy on file with the authors).

Martin, Stanley Fuld, Former Judge, Is Dead at 99, NY Times, July 25, 2003, at A21, col 1.

Pollack, Tribute to Retiring Chief Judge Fuld: Great Judge in the American Tradition, NYLJ, December 28, 1973, at 1, col 2.

Reese, Chief Judge Fuld and Choice of Law, 71 Colum L Rev 548 (1971).

Scileppi, Stanley Fuld-A Judge’s Judge, NYLJ, Jan. 24, 1974, at 34, col 1.

Sovern, Chief Judge Stanley H. Fuld, 71 Colum L Rev 545 (1971).

Stein, Stanley H. Fuld: A Life Lived in the Law, 104 Colum L Rev 258 (2004).

Stein, Remembering Stanley Fuld, NYLJ, Apr. 8, 2004, at 2, col 3.

Uviller, The Judge at the Cop’s Elbow, 71 Colum L Rev 707 (1971).

Weinstein, In Memoriam: The Honorable Stanley H. Fuld, 104 Colum L Rev 253 (2004).

Weinstein, The Honorable Stanley H. Fuld, The Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York, Spring/Summer 2004, at 1.

Published Writings Include:

Tribute, 43 Rutgers L Rev 505 (1990-91) (in honor of Edward J. Bloustein).

Foreword, 36 Copyright L Symp vii (1989) (coauthored with Robert B. McKay and Herman Finkelstein).

A Tribute to Chief Judge Charles S. Desmond, 36 Buff L Rev 6 (1987).

Willis L.M. Reese, 81 Colum L Rev 935 (1981).

Foreword 23 Copyright L Symp vii (1977) (coauthored with Robert B. Williamson).

Foreword, 19 NYLF 741 (1973-74).

Professor Milton Handler, 73 Colum L Rev 404 (1973).

Introduction, 36 Brook L Rev 329 (1969-70) (issue on judicial administration).

The Right to Dissent: Protest in the Courtroom, 44 St. John’s L Rev 591 (1969-70).

Foreword, 17 Copyright L Symp v (1969).

Symposium in Memory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 68 Colum L Rev 1017 (1968).

Charles S. Desmond: A Judge for the Changing Years, 15 Buff L Rev 258 (1965-66).

Edmond Cahn, 40 NYU L Rev 210 (1965).

The Voices of Dissent, 62 Colum L Rev 923 (1962).

Commission and the Courts, 40 Cornell LQ 646 (1954-55).

Foreword, 5 Copyright L Symp v (1954) (coauthored with Leon R. Yankwich).

A Judge Looks at the Law Review, 28 NYU L Rev 915 (1953).

The LawyerCMore Than Advocate, 15 Alb L Rev 1 (1951).

The Writ of Error Coram Nobis, NYLJ, June 17, 1947, at 6, col 1.

Developments and Directions in Criminal Law, District Attorneys’ Association of the State of New York (1944).

Endnotes

- Note, Streamlining the Indictment, 53 Harv L Rev 122, 122 (1939).

- Dewey, The Making of a Judge, 71 Colum L Rev 537, 541 (1971), quoting Fuld, The Writ of Error Coram Nobis, NYLJ, June 7, 1947, at 6, col 1 (emphasis in original).

- See e.g. Carey v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp., 11 NY2d 452 (1962), rev’d, 375 US 261 (1964); compare Pleasant Valley Packing Co., Inc. v. Talarico, 5 NY2d 40 (1958), with San Diego Bldg. Trades Council, Millmen’s Union, Local 2020 v. Garmon, 359 US 236 (1959), and Int’l Assoc. of Machinists, 297 NY 519, with United Steelworkers of Am. v. Am. Mfg. Co., 363 US 564 (1960).

- Compare Eisen v. Post, 3 NY2d 518 (1957), with BCL ‘ 909(a), and Matter of Radom & Neidorff, Inc., 307 NY 1 (1954), with BCL ” 1104(a)(3), 1111, and Gordon v. Elliman, 306 NY 456 (1954), with BCL ‘ 627, and Schwarz v. Gen. Aniline & Film Corp., 305 NY 395 (1953), with BCL ‘ 723.