Introduction

Anyone preparing a portrait of Benjamin Nathan Cardozo would necessarily approach the task with great trepidation. Already there are so many wonderful writings about him, most especially Professor Andrew Kaufman’s 731-page masterpiece, which took more than 41 years to complete.1 Surely, by now everything about Cardozo has been said. Moreover, the man and his work were, and remain, objects of reverence. As Professor Kaufman observes, “Cardozo’s record and reputation have made him a point of comparison for other judges, usually in terms of a judge or judicial nominee falling short of the mark, as being ‘no Cardozo.'”2 He set the standard of judicial excellence for his day, and he continues to set the standard of judicial excellence for ours.

Family and Early Years

Benjamin Nathan Cardozo and his twin sister, Emily Natalie, were born in New York City on May 24, 1870 into an elite, prominent, Sephardic Jewish family, the fifth and sixth surviving children of Albert Jacob and Rebecca Nathan Cardozo.3

Despite a glorious heritage, his childhood was not an easy one, beginning with feeble health in his first days of life. Weeks later, his mother’s brother, Benjamin Nathan (for whom he was named), vice president of the New York Stock Exchange and president of Congregation Shearith Israel (the family’s house of worship), was brutally murdered when returning home from services. Controversy swirled for months, but the murderer was never found. When Cardozo was two years old, his father, at the pinnacle of his career as a Justice of the New York State Supreme Court, was compelled to resign the bench in disgrace amid charges of corruption during the William “Boss” Tweed era. And though he managed as a lawyer to maintain his family in comfort, theirs always was a solitary, reclusive life.4 Cardozo’s mother, long chronically ill, died when he was nine years old, leaving his upbringing largely to his sister Ellen (Nell), eleven years his senior, with whom he made his home — neither of them married. Indeed, only one of his siblings (his twin, Emily) married (she married a Christian, and was declared dead by the family). In 1885, the year Cardozo entered Columbia College, at age 15, both his sister Grace and his father died.5

Add to these tragic events the centrality of Congregation Shearith Israel — the nation’s oldest synagogue, orthodox and formal in its traditions — in Cardozo’s early life. Cardozo’s father for a time served as vice president; several family members were presidents and ministers of the Congregation, including his great-granduncle, who in August 1776 fled New York City with the Holy Scrolls to escape invading British forces. In the family, no detail of religious observance was neglected. When Cardozo’s father was required to be at the courthouse on Saturdays, he first consulted the Beth Din (the rabbinic court of law) in London, learned that necessary public business took precedence, and after services walked to the courthouse.6

Inevitably, Cardozo’s early years shaped the person he became.

First, it is plain that he was a person of extraordinary intelligence and that he found pleasure, and refuge, in study. Superbly educated at home by Horatio Alger (who transmitted his love of poetry to his student), Cardozo clearly enjoyed learning, read widely, and had a flawless memory. By the age of 15, he had passed Columbia University’s five-day examination covering, among other things, English, Latin, and Greek grammar; Greek and Latin prosody (the rhythmic and intonational aspect of language); Greek, Latin, and English composition; modern geography and ancient history; arithmetic, algebra, and geometry. Latin and Greek, and then German or French, readings were required during most of his four-year undergraduate program.7 As the 1889 Columbia yearbook described him:

‘Tis he, ’tis Nathan, thanks to the Almighty.

Women and men he strove alike to shun,

And hurried homeward when his tasks were done.8

At 19, Cardozo graduated at the top of his class, voted by his classmates “cleverest” and second “most modest.”9 Then, while at Columbia Law School, he broadened his studies by additionally enrolling both in Columbia’s Faculty of Philosophy and in its School of Political Science, earning a Master of Arts degree in June 1890. There he learned to look to the spirit as well as the letter of the law. Cardozo withdrew from law school in 1891, one year short of graduation, to enter his brother’s law practice.

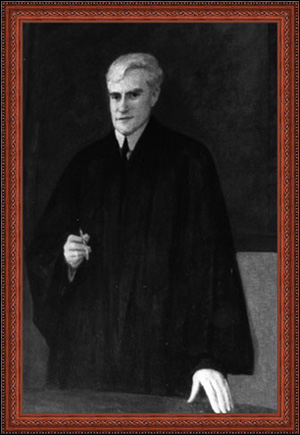

Related to his love of books and learning is Cardozo’s lifelong quality of modesty, gentility, and reticence, evident even in his visage.10 As artist William Meyerowitz wrote, “The extreme delicate and sensitive forms of his face, his penetrating eyes under his heavy eyebrows, gave one an impression never to be forgotten.”11 Though of great personal charm in his dealings with others, Cardozo lived a life of intense privacy and intellectual meditation, the life of a scholar. Second Circuit Chief Judge Learned Hand described his friend in these words:

He was wise because his spirit was uncontaminated, because he knew no violence, or hatred, or envy, or jealousy, or ill-will. I believe it was this purity that chiefly made him the judge we so much revere; more than his learning, his acuteness and his fabulous industry.12

He was, in short, much loved and admired, for qualities that set him apart from others. One writer has suggested that “by the unanimous testimony of his contemporaries, Cardozo was a saint.”13 His biographer, Professor Kaufman, exposes a few signs of imperfection. For example, we learn that Cardozo courted academics who in return showered him with praise, and that he fussed over his clothing and famous “tousled hair.”14 Kaufman also reveals some of Cardozo’s attitudes on race and gender that, although common at the time, unsettle the modern reader.15

We also know a third lifelong quality likely traceable to Cardozo’s early family history: his sense of rectitude, responsibility, and dedication to duty — duty to the law, duty to his family, duty to his family name.16 Happily, however, we also know that Cardozo’s personal life was neither “a cold nor an empty one.”17 His circle of friends and family filled whatever little leisure time he had, and he was surrounded by people fiercely devoted to him. His law office staff and court staff loved him, his housekeeper of 46 years said he was “the most unique and lovable soul I have ever known,” even Albany hotel personnel spoke of his kindness.18

One final thought on Cardozo’s early influences. After his Bar Mitzvah at age 13, Cardozo remained a member of Shearith Israel — he was known as a Sephardic Jew, and apparently drew a significant part of his law practice from that affiliation — but in his level of religious observance he became a somewhat distant member. At a commencement address delivered at the Jewish Institute of Religion on his 61st birthday, Cardozo acknowledged that he was unable to claim that the beliefs of the students there assembled were “wholly [his]” or “that the devastating years have not obliterated youthful faiths.”19 In a letter to a friend two years before his death, Cardozo wrote:

I think a good deal these days about religion, wondering what it is and whether I have any. As the human relationships which make life what it is for us begin to break up, we search more and more for others that transcend them.20

Despite this admission, Cardozo throughout his life held “fast to certain values transcending the physical and temporal.”21 “So, in our own body of law,” he wrote, “the standard to which we appeal is sometimes characterized as that of justice, but also as the equitable, the fair, the thing consistent with good conscience,”22 “the principle and practice of men and women of the community whom the social mind would rank as intelligent and virtuous.”23 One early biographer who knew the family summed up these qualities as follows: “Cardozo had reverence for the past. He was, it must not be forgotten, an aristocrat by descent. Certainty, order, coherence, that make for the ‘symmetry of the law’ meant to him what a sonnet means to a poet.”24

Aristocrat, scholar, bookish, formal, reclusive, withdrawn, modest; imbued with a sense of rectitude, responsibility, dedication to duty, and a reverence for the past. Surely, there was a lot more to Cardozo — as he would shortly show the world.

Prelude to the Court of Appeals

At the tender age of 21, Benjamin Nathan Cardozo embarked on the career to which he singly dedicated his life: the law. For 23 years as a New York City practitioner, he enjoyed acclaim as a “lawyer’s lawyer,” a walking encyclopedia of law. His knowledge was astounding, his memory photographic. He could prepare a brief, including references to all pertinent cases and materials, simply from memory.

In his very first year in his brother’s practice — apparently a highly successful firm — Cardozo argued five appeals and won four; within five years, he had argued 24 appeals. After one argument before the Court of Appeals, the Chief Judge reportedly asked him to stop by, and complimented him on his presentation.25 His busy, lucrative law practice — largely commercial law — appears to have been drawn mainly through the Jewish business and legal community. While skilled in both trials and appeals, he was for the most part retained by lawyers to argue difficult law issues. Kaufman’s comprehensive chapters establish that Cardozo was a tough, resourceful lawyer. As one friend observed:

“He was unfitted for any struggle where scrupulous integrity and fine sense of what is right might be a handicap; but judges felt the persuasive force of his legal argument, and lawyers and laymen sought his counsel and assistance in the solution of intricate legal problems.”26

Evidencing both his industry and his intimate familiarity with the Court of Appeals and its work, Cardozo managed in 1903 in addition to a busy law practice to publish a book, The Jurisdiction of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York, which merited an updated, second edition in 1909.

The year 1909 was significant for yet other reasons: based on his reputation, Cardozo, then 39, was sought out for appointment to the Federal District Court. The death of his brother Albert that same year added even further to his responsibility for support of the household — by then a townhouse for himself, his sister Nell and staff at 16 West 75th Street — and he declined for financial reasons.27 Barely four years later, opportunity knocked again. This time Cardozo (a Democrat) was asked to run for State Supreme Court on the Fusion ticket, and he accepted. Financial considerations were less an obstacle, because the State bench paid far more than the federal salary at that time. But even more important, Supreme Court was the court from which his father had resigned in 1872 under charges of corruption. Cardozo bore that stain like a personal wound and several times expressed the desire to restore his family’s honor.

Cardozo’s reputation apparently enabled him to avoid not only the maneuvering required to win nomination, but also the campaigning required to win election. He was ardently supported by the leaders of the New York bar, and endorsed by major newspapers. Nonetheless, political forces made the election close. Cardozo jested that his victory over Bartow Weeks was due to the support of Italian-American voters who believed from his name that he was of Italian descent.28

Cardozo never filled out his term as a trial judge — indeed, he never really began it. At that time, because the Court of Appeals had a huge backlog of cases, the Governor made three additional temporary appointments to the Court from the ranks of Supreme Court Justices. Although Governor Martin Glynn was concerned about Cardozo’s lack of judicial experience — he had not yet even written his first judicial opinion — the Court of Appeals Judges, who traditionally recommended candidates to the Governor for these temporary positions and knew Cardozo’s qualities firsthand, urged Glynn to designate Cardozo. In February 1914, Glynn appointed Cardozo to fill a three-year temporary position on the Court of Appeals. Years later the Governor said he was prouder of that designation than any other act of his career. On January 15, 1917, Governor Charles Whitman appointed Cardozo to fill the vacancy created when Samuel Seabury resigned to accept the Democratic nomination for Governor. Cardozo retained that seat by winning (with bipartisan endorsement) election as an Associate Judge later that year. In 1926, again with bipartisan endorsement, Cardozo was elected Chief Judge.

The Court of Appeals Years

The 18 years Cardozo served on the Court of Appeals — 1914 to 1932 — surely must have been the happiest, most fulfilling years of his life.29 There is ample contemporaneous evidence for that conclusion in Cardozo’s own words, in his prodigious writings (both judicial and jurisprudential), and in the open adoration of the legal community and the public at large. According to a 1930 New Yorker profile, “hard-boiled lawyers” compared him to a “saint, a medieval scholar, and Abraham Lincoln”; and the deans of Harvard, Yale, and Columbia Law Schools unsuccessfully importuned President Harding to appoint him to the United States Supreme Court; his Court of Appeals brethren regarded him with a mixture of “awe and protective tenderness.”30

Most touching, and perhaps most enlightening about what Cardozo’s years on the Court of Appeals were actually like, are the words his colleague Cuthbert W. Pound spoke on March 3, 1932, the day Cardozo left Albany for Washington. Emotion leaps off the page. Addressing him as “Beloved Chief Judge,” Judge Pound said:

The bar knows with what earnestness of consideration, firmness of grasp, and force and grace of utterance you have made your power felt; with what evenness, courtesy and calmness you have presided over the sessions of the court. Only your associates can know the tender relations which have existed among us; the industry with which you have examined and considered every case that has come before us; the diligence with which you have risen before it was yet dawn and have burned the midnight lamp to satisfy yourself that no cause was being neglected. At time your patience may have been tried by the perplexities of counsel and of your associates, but nothing has ever moved you to an unkind or hasty word. You have kept the court up with its calendar by promoting that complete harmony of purpose which is essential to effective work. The rich storehouse of your unfailing memory has always been open to us.

We shall miss not only the great Chief Judge whose wisdom and understanding have added glory to the judicial office but also the true man who has blessed us with the light of his friendship, the sunshine of his smile.31

However felicitous the personal associations may have been, clearly it was the work of the Court that Cardozo loved. He was superbly suited to that common law court — an extraordinary person for an extraordinary process — molding out of the clay of everyday human experience principles that not only resolved immediate controversies but also guided conduct long into the future. As Cardozo himself explained the work of the Court in his 1909 treatise: “The wrongs of aggrieved suitors are only the algebraic symbols from which the court is to work out the formulate of justice.”32 His skill was to see “the general in the particular,”33 and then to clothe his writings in a rich and majestic style that endured in the mind of the reader. “Conservative in his habits, his dress, his manners, and in most of his opinions, he [was] a great liberalizer of the law.”34

Take, for example, MacPherson v. Buick Motor Company.35

Astoundingly, in 1916, while still a temporary Court of Appeals judge, shortly after leaving private practice, Cardozo succeeded in persuading three of his colleagues over the dissent of then Chief Judge Willard Bartlett to join him in abandoning the traditional requirement known as “privity” and allowing the buyer of an automobile with a defective wheel to sue the wheel manufacturer directly. The vote alone is breathtaking evidence of Cardozo’s confidence and conviction, as well as the esteem in which he was held, even at the very outset of his judicial career.36

In MacPherson, Cardozo and Bartlett looked at the same set of facts, but Cardozo saw the potentiality of the automobile and the principle of law. While a common law high court’s role is to “declare and settle” the law,37 both the immediate consequences of a broad rule and the long-term impact of stare decisis are strong moderating influences: if we adopt this principle today, where will it take the law in the next, unforeseeable cases?38 Another brand-new junior judge might have found the circumstances intimidating, taking respectable refuge on narrower ground.

Cardozo, however, writing for a bare majority of four,39 saw a green light of opportunity rather than a signal for caution. Plowing through a line of cases generally recognized as exceptions to the general no-liability-without-privity rule, he extracted a new principle that unified the exceptions: foresight of danger creates a duty to avoid injury.40 The exceptions now became the rule. A new product, the automobile, had created new dangers; the law would therefore evolve to create new protections. His opinion breathes with the elasticity and forward progress of the common law:

“Precedents drawn from the days of travel by stage coach do not fit the conditions of travel to-day. The principle that the danger must be imminent does not change, but the things subject to the principle do change. They are whatever the needs of life in a developing civilization need them to be.”41

His bold reasoning is, moreover, lit by learning and literary style. Succinctly, he reviews New York cases, federal decisions, British cases, other states’ holdings, as well as treatises and academic commentators. And while MacPherson does not display Cardozo’s most distinctive prose, the language is forthright and strong:

“We have put aside the notion that the duty to safeguard life and limb, when the consequences of negligence may be foreseen, grows out of contract and nothing else. We have put the source of the obligation where it ought to be. We have put its source in the law.”42

Chief Judge Bartlett, by contrast, wrote a fact-bound, “technically sound”43 but crabbed dissent. He saw only a creaky runabout and stayed with stagecoach precedents. Plaintiff’s automobile, after all, was traveling at a speed of only eight miles an hour — barely outrunning the stagecoach — at the time of the accident; Buick had purchased this wheel from a reputable manufacturer that had previously furnished 80,000 wheels, none defective; if the rule allowing suit by a subvendee against a manufacturer was to be enlarged, let that be for the legislature. As Judge Richard Posner observed, MacPherson has proved itself “the quietest of revolutionary manifestos,”44 the perfect vehicle to guide the law of torts in an increasingly motorized, mobile, mass produced society.

Viewed narrowly, MacPherson involved a one-car accident on a country road. But seen in another light it raised an issue emblematic of a society that was becoming increasingly motorized, mobile and mass-produced: should a manufacturer be liable for injuries sustained by a remote purchaser of a defective product?45 The general rule — based on a case involving a stagecoach accident — limited liability to those with whom the manufacturer was “in privity,” with exceptions for fraud and inherently dangerous products, like poisons. In MacPherson, Cardozo grasped the larger implications of the village stonecutter’s vehicular misfortune, and forged a new rule to better serve the emerging social realities.

Meinhard v. Salmon is a second Cardozo classic — there are so many! One may forget the details of the dealings between the real estate operator Walter J. Salmon and the wool merchant Morton H. Meinhard, but never Cardozo’s ringing words:

“A trustee is held to something stricter than the morals of the marketplace. Not honesty alone, but the punctilio of an honor the most sensitive, is then the standard of behavior.”46

Chief Judge Lehman later acknowledged that he hesitated over whether he would deliver the critical fourth vote to Judge Cardozo or to Judge Andrews, but concluded that few words contained in any judicial opinion had a greater or more salutary effect than the quoted words that flowed from Cardozo’s pen.47 Although Salmon had fully conformed to the commercial ethics code of the nineteenth century, Cardozo understood that the code was simply inadequate for the twentieth. So he created a new standard. A fascinating analysis by Nicholas Georgakopoulos in the 1999 edition of the Columbia Business Law Review credits Cardozo’s standard with facilitating the financing of modern business ventures by allowing passive investors to expect a greater portion of a project’s remote potential.48 Not a bad day’s work in the year 1928.

What extraordinary talents Cardozo had to see the opportunity, to win over at least three colleagues, and then to fashion a sensible, exquisitely expressed rule that is timeless.

Professor Kaufman’s consistent conclusion is that Cardozo “was, and only aimed to be, a modest innovator”;49 that, as a person to whom the values of tradition and order were important, he was only a “cautious” innovator.50 Others authoritatively second that conclusion. Cardozo was surely no firebrand. Yet as so many of his Court of Appeals opinions show, in at least two important respects, as a judge he was bold: he thought globally — he looked beyond the immediate facts to the future course of the law — and he wrote daringly.51

From his “search for the just word, the happy phrase”52 to his “groupings of fact and argument and illustration so as to produce a cumulative and mass effect,”53 literary style mattered to Cardozo. People differ about the “architectonics” (Cardozo’s word)54 of his opinions — there is a hearty band on both sides of this issue.55 But whether one’s literary taste runs to the florid or the frugal, Cardozo is without doubt among America’s most quotable judges. Professor Kaufman suggests the following candidates for “legal writing’s Hall of Fame”:56

“Metaphors in law are to be narrowly watched, for starting as devices to liberate thought, they end often by enslaving it.”

“The tendency of a principle to expand itself to the limit of its logic may be counteracted by the tendency to confine itself within the limits of its history.”

“Danger invites rescue.”

“The assault upon the citadel of privity is proceeding in these days apace.”

Favorite among Cardozo’s literary flights was the technique of sentence inversion: “Not lightly vacated is the verdict of quiescent years.”57 Vivid. Attention-getting. Memorable. “To this hospital the plaintiff came in January 1908.”58 Well chalk one up for the other side.

Cardozo advocated for sparse statements of fact in judicial decisions,59 and his opinions prove that this approach can yield arresting results. Who, after all, can forget the defendant who “style[d] herself ‘a creator of fashions,'” whose “favor help[ed] a sale?”60 Or the sketch of events on the Long Island Railroad platform that immortalized Helen Palsgraf?61 Or the terse account of George Kent’s pursuit of plumbing perfection for his pricey country residence?62 The wealth of detail in Kaufman’s book gives a glimpse of the types of facts Cardozo left on the cutting room floor: that Mrs. Palsgraf’s principal injury was a stutter allegedly caused by the accident, that Mr. MacPherson suffered his accident while driving a sick neighbor to the hospital.63 While some judges might have opted for more atmospherics, Cardozo knew when too many facts impeded the force of his legal argument.

Time and again throughout his opinions, Cardozo shows not only an ability to perceive precisely the right balance that will “settle and declare the law” but also a gift to articulate it persuasively, in words that fix the principle forever. A lawyer’s lawyer, he thought rigorously and wrote vigorously what better description of a jurist’s jurist?

The Storrs Lectures

Cardozo’s first — and best known — jurisprudential exposition was The Nature of the Judicial Process, delivered in February 1921 as the Storrs Lectures at the Yale Law School. His performance in New Haven was, by all accounts, mesmerizing. Professor Kaufman quotes Arthur Corbin:

Standing on the platform at the lectern, his mobile countenance, his dark eyes, his white hair, and his brilliant smile, all well lighted before us, he read the lecture, winding it up at 6 o’clock. He bowed and sat down. The entire audience rose to their feet, with a burst of applause that would not cease. Cardozo rose and bowed, with a smile at once pleased and deprecatory, and again sat down. Not a man moved from his tracks; and the applause increased. In a sort of confusion Cardozo saw that he must be the first to move. He came down the steps and left, with the faculty, through a side door, with the applause still in his ears.64

“Never again have I had a like experience,” Corbin wrote. “Both what he had said and his manner of saying it had held us spell-bound on four successive days.”65

Cardozo’s statement early on in the first of the Storrs Lectures — “I take judge-made law as one of the existing realities of life” — was seen by some as an admission verging on heresy.66 As Kaufman makes clear, Cardozo was not the first to espouse such a view.67 Yet his account seems to have struck a nerve others missed. The word was out: judging is more than a matter of “match[ing] the colors of the case at hand against the colors of many sample cases spread out upon [a] desk.”68 It is an endeavor marked — within limits — by indeterminacy and discretion, by creativity and choice.

In the lectures, Cardozo explored four interrelated “methods” of deciding cases when existing precedents do not determine the controversy at hand: logic (“the method of philosophy”); history (“the method of evolution”); the customs of the community (“the method of tradition”); and “justice, morals and social welfare, the mores of the day” (“the method of sociology”).69 He posited a functional approach to law — the ultimate test of legal rule is not how well it fits in some abstract theory, but how well it actually performs in the real world.

Although at the time a judge of the New York State Court of Appeals — where common law, not constitutional issues dominated the docket — Cardozo made special note of the applicability of his approach to constitutional adjudication. While the words and phrases enshrined in the Constitution were unchanging, their meaning varied with time: “a constitution states or ought to state not rules for the passing hour, but principles for an expanding future.”70 Judges must therefore construe constitutional concepts flexibly, in light of current conditions and with due respect for the judgments of the legislative branch. When reviewing statutes, judges must be careful not to substitute “their own ideas of reason and justice for those of the men and women whom they serve.”71

Some have observed that Cardozo’s outline is “not very helpful in the decision of actual cases.”72 True, The Nature of the Judicial Process provides no algorithm for judging. Yet it is no brief for nihilism either.73 Cardozo is careful to stress the limits on a judge’s discretion,74 and he notes that stability and predictability play a significant role in a well-ordered society.75 But he recognizes that ultimately, the issue comes down to individual wisdom and humanity:

If you ask how [a judge] is to know when one interest outweighs another, I can only answer that he must get his knowledge just as a legislator gets it, from experience and study and reflection; in brief, from life itself.76

The Nature of the Judicial Process stated Cardozo’s juridical philosophy; his opinions applied it. Clearly, he was preaching what he practiced. From the bench of the Court of Appeals, he inveighed against “the dangers of ‘a jurisprudence of conceptions,'”77 chastising those “who think more of symmetry and logic in the development of legal rules than of practical adaptation to the attainment of a just result. . . .”78 He used his four “methods” in deciding cases, and made no attempt to hide it.79 His common law opinions drew upon accepted notions of justice and reasonable conduct, such as he saw them, to decide individual disputes and lay down guidelines for future action.80 And even his most progressive decisions stress the continuity of the common law — the stability of the system, if not the precise application of doctrines, over time.

After first explaining that the result in most cases is foreordained by precedents of the past, Cardozo writes that he has become more and more reconciled to uncertainty: “I have grown to see that the process in its highest reaches is not discovery but creation; and that the doubts and misgivings, the hopes and fears, are part of the travail of mind, the pangs of death and the pangs of birth, in which principles that have served their day expire, and new principles are born.” The confession that judges actually made law instead of simply applying existing precedents, was regarded, as one commentator observed, as a legal version of hard-core pornography; a less saintly man, he adds, would have found himself close to impeachment for such expressions.81

To this day Cardozo’s exposition of the nature of the judicial process and the growth of the law remains new and exciting. It’s an excellent read!

Career on the Supreme Court

In 1932, President Herbert Hoover appointed Cardozo to the Supreme Court of the United States, to succeed his idol, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. Cardozo served a brief six years, until his death at the age of 68 in 1938. From Washington, he wrote of homesickness and loneliness for his Court of Appeals life and his New York City life.

At the Supreme Court, Cardozo continued to follow a pragmatic, case-by-case approach. He decided the issues before him on the facts of the cases, leaving further glosses and extensions to the future.82 He also advocated for a flexible construction of constitutional restraints upon regulation of economic matters, frequently voting — often in the minority — to uphold legislative efforts to improve social and economic conditions.83 Cardozo’s support of New Deal legislation caused him to be viewed as a “liberal,” but his approach to cases was a method not an ideology. As Professor Kaufman suggests, “most judges still go about the job of deciding cases within the framework that Cardozo described.”84

Cardozo’s Impact on the Law

The 68 years of Benjamin Nathan Cardozo’s life spanned a period of enormous social change — society became more highly industrialized, we had a great war and a great depression. His genius as a Judge was in maintaining the order, certainty, and regularity of the law while at the same time recognizing that no judge-made rule can or should survive when it has gone out of harmony with the thoughts and customs of the people. He applied existing doctrines to contemporary problems with wisdom and discretion, leaving an indelible mark in the evolutionary process of the law.

Though Cardozo’s impact was felt in every field of the law, his greatest influence was in “deepening the spirit of the common law.”85 Sixty years ago, he perceived, for example, that an automobile was a potentially dangerous instrument and sustained recovery by an injured person on a broader basis than had previously been recognized; he held the fiduciary to the highest ethical standards; he extended the reaches of liability in some areas of law, and yet limited recovery against public utilities and others on policy grounds where liability otherwise would be crushing. He found implied promises and constructive trusts to achieve the just result in contract cases, and laid sturdy foundations for development of the law away from mechanical application of principles that barred enforcement of promises. And always his opinions were of incomparable beauty, because of his ability and because he believed that judicial writing was also literature, and that form of expression had importance.

Cardozo’s career placed him on two significant courts during two watershed periods: the New York Court of Appeals from 1914 to 1932, when many basic common law principles were being tested in light of new social and economic realities, and the United States Supreme Court from 1932 to 1938, when cataclysmic battles raged over the constitutional status of the regulatory state. Cardozo distinguished himself in both roles — although without question, he is best remembered for his work as a common law judge.86

As a man who believed in progress and accepted the fact of change, Cardozo understood that time would take its toll on even the best judges’ work:

“The work of a judge is in one sense enduring and in another sense ephemeral. What is good in it endures. What is erroneous is pretty sure to perish. The good remains the foundation on which new structures will be built. The bad will be rejected and cast off in the laboratory of the years.”87

Cardozo has clearly passed his own test with flying colors. In this day when opinion polls seem to settle so many contested issues, Judge Posner’s computerized calculations of Cardozo’s standing are one good source for gauging his current value. The data show that Cardozo stands head and shoulders above the next-best-known state court judge, Roger Traynor, in citations in academic writings. He is consistently cited ahead of his Court of Appeals colleagues by state and federal courts, and leads them all in opinions in torts and contracts casebooks. His federal jurisprudence also left its mark: in the last decade, Cardozo’s Supreme Court opinions were cited more frequently than those of his most highly regarded colleagues — Harlan Fiske Stone and Louis Brandeis — from the same period.88

While those statistics are surely impressive, even more meaningful for the Court of Appeals “family” is the fact that Cardozo’s writings remain significant in the Court’s decisionmaking process. The changes in the landscape since Cardozo’s day are manifest. Technology is obviously different: MacPherson’s runabout would be left in the dust on the New York Thruway. Social relations are also different thanks to the civil rights movement and a sexual revolution. The legal landscape is different too: since Cardozo’s day, we have witnessed relentless “statutorification”89 of the law, with legislation displacing the common law in many areas as the primary source of legal precepts.90

Yet in this vastly changed world, Cardozo’s opinions continue to shine as a polestar for the resolution of disputes. “The Flopper” may be long gone from the Coney Island boardwalk, but just recently the basic principles of Murphy v. Steeplechase Amusement Co., Inc.91 lived on in fixing the responsibility of sport facilities that cater to some of today’s popular recreational pursuits: indoor tennis and karate.92 The primitive firefighting system at issue in Moch Co. v. Rensselaer Water Co.93 has also gone by the boards, but its conclusion that the zone of duty may be limited to avoid crushing levels of liability helped resolve a suit that arose from the last New York City blackout.94 Stony Point, New York, may no longer be merely a place of little cottages and fields, as it was in Cardozo’s day, but the rule of People v. Tomlins95 remains unwavering that a person under attack has no duty to retreat from his or her own home. “Evil practices” are, of course, no longer “rife” among members of the bar, but when individuals in the professions are investigated for wrongdoing, we adhere to the admonition of People ex rel. Karlin v. Culkin96 that “[r]eputation in such a calling is a plant of tender growth, and its bloom, once lost, is not easily restored.”

Some controversies, alive and well before and during Cardozo’s time, such as the tension recognized in Beecher v. Voght Mgt.,97 between an attorney’s right to collect under a charging lien and another’s right to a setoff, remain alive and well today.98 And while a particular dispute over attorney’s fees in Prager v. New Jersey Fidelity & Plate Glass Ins.99 has long since been extinguished, the rule lives on that the purpose of awarding interest is to make an aggrieved party whole.100 In matters of statutory interpretation so important today his canons of construction continue to guide the Court.101 And frankly, does any reader searching for the basic rule governing severability need to consult the books to know its author? The poet’s touch is evident:

Severance does not depend upon the separation of the good from the bad by paragraphs or sentences in the text of the enactment. The principle of division is not a principle of form. It is a principle of function. The question is in every case whether the legislature, if partial invalidity had been foreseen, would have wished the statute to be enforced with the invalid part exscinded, or rejected altogether. The answer must be reached pragmatically, by the exercise of good sense and sound judgment, by considering how the statutory rule will function if the knife is laid to the branch instead of at the roots.102

Cardozo’s bean weigher in Glanzer103 and accountant in Ultramares104 were central to the Court’s definition of duty for contemporary architectural engineers105 and worldwide accounting firms.106 And to this day, Mrs. Palsgraf regularly resurfaces in modern dress — one of her last appearances as a nurse injured by a falling wall fan, seeking recovery against a maintenance company under contract with the hospital.107 Court of Appeals decisions continue to cite Cardozo, building upon precedents of an earlier age to fit the law to modern society, blending a phrase from the Hall of Famer, borrowing the halo that surrounds his work.

Of course, not all of his opinions have withstood the test of time. The rule of Schloendorff v. New York Hospital108 — exempting charitable hospitals from liability for the negligence of its medical staff — was found to be “at variance with modern-day needs and with concepts of justice” in Bing v. Thunig.109 Mapp v. Ohio110 paid homage to Cardozo’s image of the blundering constable, but overruled People v. Defore111 all the same.

While time may have undermined some of Cardozo’s holdings, it has not eroded the vitality of his description of the judicial process.112 Debates over whether judges “find” law or make it, and what sources they should draw upon when rendering a decision, continue to this day.113 Cardozo stated the case for dynamic (yet restrained) judicial innovation as well as anyone has, or probably will. Across the decades, his voice still elevates the discourse:

The judge, even when he is free, is still not wholly free. He is not to innovate at pleasure. He is not a knight-errant roaming at will in pursuit of his own ideal of beauty or of goodness. He is to draw his inspiration from consecrated principles. He is not to yield to spasmodic sentiment, to vague and unregulated benevolence. He is to exercise a discretion informed by tradition, methodized by analogy, disciplined by system, and subordinated to “the primordial necessity of order in the social life.114

Nor has time dulled the brilliance of Cardozo’s prose. Today’s judges need not copy his ornate style flourish for flourish — what tripped off the tongue 70 years ago sometimes sticks in the throat today. Yet appellate judges must struggle to find the elusive phrase, the expression that will capture and fix the principle that controls the case. To make a rule and make it memorable: this occurs only at the intersection of law and literature, a juncture Cardozo — but few other judges — frequented.115

His Death

Cardozo died on July 9, 1938. He was buried alongside his family in Beth Olom Cemetery (also known as Congregation Shearith Israel Cemetery) located on Cypress Hills Street in Brooklyn. While praises of Cardozo were received the world over, at his funeral, as he had requested, only the traditional Sephardic prayers were recited. There was no eulogy, and no word of English. As Irving Lehman (a close friend and colleague, himself later a distinguished Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals) said of him in a memorial service at the City Bar Association:

“There is little of drama in this brief record of Justice Cardozo’s life. It was a life of fruitful thought and study, not of manifold activities. Quiet, gentle and reserved, from boyhood till death he walked steadily along the path of reason, seeking the goal of truth; and none could lure him from that path.”116

Progeny

From Benjamin Nathan Cardozo, his brother and four sisters, there are no progeny.

There are, however, some notable cousins. Among the Nathans are sisters Maud Nathan and Annie Nathan Meyer (one of the founders of Barnard College), Emma Lazarus, and New York City lawyer-brothers Frederic S. and Edgar J. Nathan 3rd (and their sisters and children), who to this day are prominent members of Congregation Shearith Israel. On the Cardozo side, the “Michael H. Cardozos” (tracing their lineage back to Ellen and Michael Hart Cardozo [1800-1855]) are up to Michael H. Cardozo VI. Ellen and Michael Hart Cardozo were Judge Cardozo’s grandparents. They are the great-great-great grandparents of New York City Corporation Counsel Michael A. Cardozo.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Selected Bibliography

Books

Gilmore, Grant, The Ages of American Law (1974).

Hall, Margaret E. (ed.), Selected Writings of Benjamin Nathan Cardozo: The Choice of Tycho Brahe (1947; 1967 reprint).

Hellman, George S., Benjamin N. Cardozo: American Judge (1940).

Kaufman, Andrew L., Cardozo (1998).

Levy, Beryl Harold, Cardozo and Frontiers of Legal Thinking (1938, rev. ed. 1969); also available as Levy, Beryl H., Cardozo and Frontiers of Legal Thinking: With Selected Opinions (paperback 2000).

Pollard, Joseph P., Mr. Justice Cardozo: A Liberal Mind in Action (1935; 1970 Greenwood Press reprinting)

Posner, Richard A., Cardozo: A Study in Reputation (1990).

COMPILATIONS OF ARTICLES117

Joint Publication of Memorial Issue in 1939 by Columbia Law Review, Harvard Law Review and Yale Law Journal

Corbin, Arthur L., “Mr. Justice Cardozo and the Law of Contracts,” 39 Colum. L. Rev. 56, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 408, 48 Yale L.J. 426 (1939).

Evatt, H.V., “Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 39 Colum. L. Rev. 5, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 357, 48 Yale L.J. 375 (1939).

Frankfurter, Felix, “Mr. Justice Cardozo and Public Law,” 39 Colum. L. Rev. 88, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 440, 48 Yale L.J. 458 (1939).

Hand, Learned, “Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 39 Colum. L. Rev. 9, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 361, 48 Yale L.J. 379 (1939).

Landis, J.M., “Law and Literature: Foreword” 39 Colum. L. Rev. 119, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 489, 48 Yale L.J. 471 (1939).

Lehman, Irving, “Judge Cardozo in the Court of Appeals,” 39 Colum. L. Rev. 12, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 364, 48 Yale L.J. 382 (1939).

Maugham, Rt. Hon. Lord, “Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 39 Colum. L. Rev. 4, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 356, 48 Yale L.J. 374 (1939).

Seavey, Warren A., “Mr. Justice Cardozo and the Law of Torts,” 39 Colum. L. Rev. 20, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 372, 48 Yale L.J. 390 (1939).

Stone, Harlan F., “Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 39 Colum. L. Rev. 1, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 353, 48 Yale L.J. 371 (1939).

Cardozo Law Review Inaugural Issue

Brubaker, Stanley C., “The Moral Element in Cardozo’s Jurisprudence,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 229 (1979).

Freund, Paul A., “Foreword: Homage to Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 1 (1979).

Kaufman, Andrew L., “Cardozo’s Appointment to the Supreme Court,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 23 (1979).

Lamm, Norman & Kirschenbaum, Aaron, “Freedom and Constraint in the Jewish Legal Process,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 99 (1979).

McDougal, Myres S., “Application of Constitutive Principles: An Addendum to Justice Cardozo,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 135 (1979).

Nagel, Ernest, “Reflections on ‘The Nature of the Judicial Process,'” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 55 (1979).

Noonan, John T., Jr., “Ordered Liberty: Cardozo and the Constitution,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 257 (1979).

Paulsen, Monrad G., “To Decide the Case at Hand — Benjamin N. Cardozo,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 219 (1979).

Weisberg, Richard H., “Law, Literature and Cardozo’s Judicial Poetics,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 283, 284, 287 (1979).

Yale Law Journal Symposium on the Judicial Process Revisted

Brown, John R., “Electronic Brains and the Legal Mind: Computing the Data Computer’s Collision with Law,” 71 Yale L.J. 239 (1961).

Clark, Charles E. & Trubek, David M., “The Creative Role of the Judge: Restraint and Freedom in the Common Law Tradition,” 71 Yale L.J. 255 (1961).

Corbin, Arthur L., “The Judicial Process Revisited: Introduction,” 71 Yale L.J. 195 (1961).

Friendly, Henry J., “Reactions of a Lawyer — Newly Become Judge,” 71 Yale L.J. 218 (1961).

Hutcheson, Jr., Joseph C., “Epilogue,” 71 Yale L.J. 277 (1961).

Van Voorhis, John, “Cardozo and the Judicial Process Today,” 71 Yale L.J. 202 (1961).

Articles

“A Personal View of Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo: Recollections of Four Cardozo Law Clerks,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 5 (1979) (contains four sections, each having a different law-clerk author: Joseph L. Rauh, Jr.; Melvin Siegel; Ambrose Doskow; Alan M. Stroock).

Abraham, Henry, “A Bench Happily Filled: Some Historical Reflections on the Supreme Court Appointment Process,” 66 Judicature 282 (1983).

Acheson, Dean G., “Mr. Justice Cardozo and the Problems of Government,” 37 Mich. L. Rev. 513 (1939).

Atkinson, David N., “Mr. Justice Cardozo: A Common Law Judge on a Public Law Court,” 17 Cal. W.L. Rev. 257 (1981).

Bellacosa, Joseph W., “Benjamin Nathan Cardozo the Teacher,” 3 Association of the Bar of the City of New York, Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lectures 1941-1995 1591, 1594 (1995) (47th Cardozo Memorial Lecture delivered November 9, 1994, at the Association of the Bar of the City of New York); also available at 16 Cardozo L. Rev. 2415 (1995).

Bodenheimer, Edgar, “Cardozo’s Views on Law and Adjudication Revisited,” 22 U.C. L. Rev. (1989).

Bricker, Paul, “Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo: A Fresh Look at a Great Judge,” 11 Ohio N.U. L. Rev. 1 (1984).

Cardozo, Michael H., “Judicial Reputation Evaluated — The Cardozo Instance,” 12 Cardozo L. Rev. 1915 (1991).

Carmen, Ira H., “The President, Politics and the Power of Appointment: Hoover’s Nomination of Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 55 Va. L. Rev. 616 (1969).

Crane, Frederick Evan, “Minute of the Court of Appeals in Reference to the Death of Honorable Benjamin N. Cardozo,” 278 N.Y. v (1938).

Deutsch, Babette, “Profiles: The Cloister and the Bench,” New Yorker, Mar. 22, 1930 at 25.

Douglas, William O., “Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 58 Mich. L. Rev. 549 (1960).

Hamilton, Walton H., “Cardozo the Craftsman,” 6 U. Chi. L. Rev 1 (1938).

Hand, Learned, “Justice Cardozo’s Work as a Judge,” 72 U.S. L. Rev. 496 (1938).

Handler, Milton & Ruby, Michael, “Essay: Justice Cardozo, One-Ninth of the Supreme Court,” 10 Cardozo L. Rev. 235 (1988).

Hessler, Stephen E., “The Story of Benjamin Cardozo, Learned Hand & the Southern District of New York,” 47 N.Y. L. Sch. L. Rev. 191 (2003).

Hyman, Jerome I., “Benjamin N. Cardozo: A Preface to His Career at the Bar,” 10 Brook. L. Rev. 1 (1940).

Kaufman, Andrew, “Adventures of a Biographer: Professor Kaufman Recounts his Forty-Year Pursuit of Cardozo,” Harv. L. Bull. (Summer 1998), available at http://www.law.harvard.edu/alumni/bulletin/backissues/summer98/article1.html (last visited Feb. 21, 2006).

Kaufman, Andrew L., “The First Judge Cardozo: Albert, Father of Benjamin,” 11 J.L. & Religion 271 (1994-1995).

Kaye, Judith S., An Appreciation of Justice Benjamin Nathan Cardozo: A Lecture by Judge Judith S. Kaye, delivered at Congregation Shearith Israel, Shabbat morning May 20, 1995 (published by the Centennial Committee of Congregation Shearith Israel, June 6, 1995).

Kaye, Judith S., A Lecture About Judge Benjamin Nathan Cardozo by Judge Judith S. Kaye, Presented at Congregation Shearith Israel, Tuesday evening, December 2, 1986 (published by Congregation Shearith Israel and Sephardic House 1986).

Kaye, Judith S., “Cardozo: A View From Eagle Street,” 49 Harv. L. Bulletin 10 (Summer 1998).

Kaye, Judith S., “Book Review: Cardozo, by Professor Andrew Kaufman,” 54 The Record 104 (January/February 1999).

Kaye, Judith S., “Book ReviewCCardozo: A Law Classic,” 112 Harv. L. Rev. 1026 (1999).

Kaye, Judith S., “Poetic Justice: Benjamin Nathan Cardozo,” American Lawyer, Dec. 6, 1999.

Lehman, Irving, “The Influence of Judge Cardozo on the Common Law,” in 1 Association of the Bar of the City of New York, Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lectures 1941-1995 15 (1995) (the First Annual Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lecture, delivered on October 28, 1941).

Manz, William H., “Cardozo’s Use of Authority: An Empirical Study,” 32 Cal. W. L. Rev. 31 (1995).

Nathan, Jr., Edgar, “Benjamin Nathan Cardozo,” The American Jewish Yearbook 5700, p.28 (1939).

Nelson, David A., “Siebenthaler Lecture: The Nature of the Judicial Process Revisited,” 22 N. Ky. L. Rev. 563 (1995).

Patterson, Edwin W., “Cardozo’s Philosophy of Law,” 88 U. Pa. L. Rev. 71 and “Cardozo’s Philosophy of Law Part II,” 88 U. Pa. L. Rev. 156 (1939).

Polenberg, Richard, “The ‘Saintly’ Cardozo: Character and the Criminal Law,” 71 U. Colo. L. Rev. 1311 (2000).

Pound, Cuthbert W., “Address to Chief Judge Benjamin Cardozo — Upon his Retirement from the Court of Appeals to Accept Appointment as Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court,” 258 N.Y. v (1932).

Powell, Lewis F., Jr., “Duty to Serve the Common Good,” 24 Cath. Law. 295 (1979).

Schwartz, Bernard, “The Judicial Ten: America’s Greatest Judges,” 1979 S. Ill. U. L.J. 405.

Schwartz, Gary T., “Cardozo as Tort Lawmaker,” 49 DePaul L. Rev. 305 (1999).

Sheintag, Bernard L., “The Opinions and Writings of Judge Benjamin N. Cardozo,” 30 Colum. L. Rev. 20 (1939).

Weisberg, Richard H., “A Response on Cardozo to Professors Kaufman and Schwartz,” 50 DePaul L. Rev. 535 (2000).

Weissman, Bernard, “Cardozo: ‘All-Time Greatest’ American Judge,” 19 Cumb. L. Rev. 1 (1988).

Published Writings and Speeches

Jurisprudence (address before the New York State Bar Association, Hotel Astor, Jan. 22, 1932).

Introduction, Selected Readings on the Law of Contracts (1931).

Law and Literature and Other Essays and Addresses (1931), a compilation that includes:

Law and Literature, Yale Review (July 1925).

A Ministry of Justice, 35 Harv. L. Rev. 113 (1921).

What Medicine Can Do for Law (address before the New York Academy of Medicine, Nov. 1, 1928).

The American Law Institute (address at the Third Annual Meeting of the American Law Institute, May 1, 1925).

The Home of the Law (Dedicatory Ceremonies of the Home of Law of the New York County Lawyers Association, May 26, 1930).

The Game of the Law and Its Prizes (address at the 74th Commencement of Albany Law School, June 10, 1925).

The Comradeship of the Bar, 5 NYU L. Rev. 1 (1928) (address at a luncheon of the New York University Law School Alumni Association, Dec. 20, 1927) .

Law and the University, 47 Law Q. Rev. 19 (1931) (address delivered at Convocation of Columbia University, Sept. 4, 1930).

Mr. Justice Holmes, 44 Harv. L. Rev. 682 (1931).

Values: The Choice of Tycho Brahe (Commencement Address delivered at the Exercises of the Jewish Institute of Religion, May 24, 1931).

Faith and a Doubting World (address before the New York County Lawyers Association, Dec. 17, 1931).

The Bench and the Bar (address before the Broome County Bar Association, March 9, 1929).

The Paradoxes of Legal Science (1928).

Our Lady of the Common Law, 13 St. John’s L. Rev. 231 (1929) (first Commencement Address at St. John’s Law School 1928).

Frank H. Hiscock, Appreciation (New York County Lawyers Association Yearbook 1927, at 257).

To Rescue “Our Lady of the Common Law”: The Dragon of Uncertainty Which Has So Long Baffled and Harried the Profession, and Which Has Threatened with Death or Dishonor “Our Lady of the Common Law,” Should Be Tracked to Its Lair and Destroyed by the Work of the American Law Institute, 10 ABA J. 347 (1924) (address delivered at the Second Annual Meeting of the American Law Institute, February 23, 1924).

The Growth of the Law (1924).

Book Review: Roscoe Pound, Introduction of Legal History, 37 Harv. L. Rev. 279 (1923).

The Nature of the Judicial Process (1921).

Identity and Survivorship, in Hamilton, Allen McLane and Lawrence Godkin, System of Legal Medicine (1909).

The Jurisdiction of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York (2d ed. 1909).

The Altruist in Politics (unpublished Commencement Oration at Columbia College, 1889).

Psychology Lectures (unpublished Notes from Benjamin N. Cardozo’s Undergraduate Classbook in the Course on Psychology Given by Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler at Columbia College).

The Moral Element in Matthew Arnold (unpublished Columbia College essay).

Endnotes

- Andrew L. Kaufman, Cardozo (1999) [hereinafter Kaufman]. This chapter borrows very liberally from Kaufman’s biography and from Judith S. Kaye: “Book Review — Cardozo: A Law Classic,” 112 Harv. L. Rev. 1026 (1999).

- Kaufman 569.

- On both sides of his family, Cardozo could trace his American roots to colonial times. Kaufman 6, 9. Cardozo once wrote to a friend that the name “Cardozo” was common in Spain and Portugal, and that someone of that name even claimed to be the Messiah. George S. Hellman, Benjamin N. Cardozo: American Judge 8 (1940); see generally Stephen Birmingham, The Grandees: American’s Sephardic Elite (1971) [hereinafter Grandees]; Rabbi Marc D. Angel, Remnant of Israel: A Portrait of America’s First Jewish Congregation (2004).

- See “A Personal View of Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo: Recollections of Four Cardozo Law Clerks,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 5, 20 (1979) (compilation of four essays written by former law clerks Joseph L. Rauh, Jr.; Melvin Siegel; Ambrose Doskow; Alan M. Stroock).

- Indeed, all of Cardozo’s siblings predeceased him; none had children. Even for the nineteenth century, when childhood illness and death were more commonplace, Cardozo’s early family portrait seems somewhat bleak. Descriptions of his early years can be found in Kaufman 1-39; Hellman 33-42; Paul Bricker, “Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo: A Fresh Look at a Great Judge,” 11 Ohio N.U. L. Rev. 1, 24-29, 32-33 (1984) (discussion of factors that helped mold Cardozo’s life, intellect, and philosophy).

- Cardozo’s religious background is described in Kaufman 23-25; Hellman 10-13; Paul Bricker, “Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo: A Fresh Look at a Great Judge,” 11 Ohio N.U. L. Rev. at 30-31; Judith S. Kaye, An Appreciation of Justice Benjamin Nathan Cardozo: A Lecture by Judge Judith S. Kaye, delivered at Congregation Shearith Israel, Shabbat morning May 20, 1995, at 2-6 (published by the Centennial Committee of Congregation Shearith Israel, June 6, 1995) [hereinafter “Shearith Israel 1995”].

- Cardozo’s early education is described in Kaufman 25-26; Paul Bricker, “Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo: A Fresh Look at a Great Judge,” 11 Ohio N.U.L. Rev. at 31-32.

- Kaufman 37-38.

- Id. at 27-39.

- Once he described himself as a “plodding mediocrity,” explaining that “a mere mediocrity cannot go far, but a plodding one can go quite a distance.” Grandees 303. See, e.g., Edgar Nathan, Jr., “Benjamin Cardozo,” The American Jewish Yearbook 5700 at 28 (1939) (“sensitively modest man”); Judith S. Kaye, A Lecture About Judge Benjamin Nathan Cardozo by Judge Judith S. Kaye, Presented at Congregation Shearith Israel, Tuesday evening, December 2, 1986, at 3 (published by Congregation Shearith Israel and Sephardic House 1986) [hereinafter “Shearith Israel 1986”] (describing his personal appearance); “A Personal View of Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo: Recollections of Four Cardozo Law Clerks,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 5, 10-11, 15, 20, 18 (1979).

- From the description accompanying an etching of Justice Cardozo included in 39 Colum. L. Rev. lii and 48 Yale L.J. i (1939).

- Learned Hand, “Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 52 Harv. L. Rev. 361, 363 (1939).

- Grant Gilmore, The Ages of American Law, 75 (1974).

- Kaufman 143, 184.

- See, e.g., Kaufman 155, 232, 404.

- As Stephen Birmingham observes, “had it not been for the family misfortunes, . . . it is quite unlikely that Benjamin Cardozo would have become the man he came to be. Because, from his earliest boyhood, he set out upon a life plan designed to exonerate, or at least vindicate, his father, and bring back honor to the Cardozo name.” (Grandees 296.)

- Kaufman 568.

- Kaufman 104, 138, 166, 183.

- Cardozo, “Values: Commencement Address, or The Choice of Tycho Brahe,” in Selected Writings of Benjamin Nathan Cardozo 1 (M. Hall ed. 1947) [hereinafter Selected Writings].

- Hellman 264-265.

- Cardozo, “Values: Commencement Address,” in Selected Writings 1.

- Cardozo, “The Paradoxes of Legal Science,” in Selected Writings 275.

- Id. at 274.

- Hellman 92. In 1895, a movement within Congregation Shearith Israel sought to “modernize” the service by, for example, eliminating gender-segregated seating, installing an organ and shortening the services. Cardozo (then age 25) made “a long address impressive in ability and eloquence” at the Synagogue meeting in opposition to all change. David & Tamar De Sola Pool, An Old Faith in the New World 375 (1955). As a consequence, today’s Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals (a woman and a member of Shearith Israel) sits upstairs.

- Babette Deutsch, “Profiles: The Cloister and the Bench,”New Yorker, March 22, 1930, p. 25.

- Irving Lehman, “A Memorial,” reprinted in Selected Writings xi.

- George Martin, CCB: The Life and Century of Charles C. Burlingham, New York’s First Citizen 1858-1959 at 187-188 (2005); Kaufman 100-101.

- The fascinating story of Cardozo’s nomination and election is more fully set forth in Martin 179-191; Kaufman 117-25. Beryl Harold Levy depicts the political scene as follows:

“Then, in November 1913, he was elected a Justice of the Supreme Court in New York City in the course of the Fusion movement which elected John Purroy Mitchel mayor. ‘As an independent Democrat, Judge Cardozo would probably never have been put forward for his first candidacy either by Tammany Hall or by the Republican organization,’ William M. Chadbourne has pointed out. And indeed, Charles C. Burlingham, chairman of the committee on judicial nominations of the Fusion Committee of 107, has related how the Republican organization held back for a time, preferring to place in nomination one of its stalwarts.” - Beryl Harold Levy, Cardozo and Frontiers of Legal Thinking 4 (rev. ed. 1969) [hereinafter Levy] (footnotes omitted). Burlingham indicated that “about seventy different people” tried to take credit for having nominated Cardozo. Id; see also Kaufman 118-19.

- But a great sadness for Cardozo, his sister Nell died in 1928.

- Babette Deutsch, “Profiles: The Cloister and the Bench,” New Yorker, March 22, 1930, at 25.

- Cuthbert W. Pound, “Address to Chief Judge Benjamin CardozoCUpon his Retirement from the Court of Appeals to Accept Appointment as Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court,” 258 N.Y. v-vi (1932). Another colleague’s highly informative insight about Cardozo’s influence at the conference table is found in Chief Judge Irving Lehman’s Cardozo Memorial Lecture — the very first — delivered at City Bar Association on October 28, 1941. Irving Lehman, “The Influence of Judge Cardozo on the Common Law,” in 1Association of the Bar of the City of New York, The Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lectures 15, 24-25 (1995).

- Benjamin N. Cardozo, The Jurisdiction of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York 11 (2d ed. 1909).

- Paul A. Freund, “Foreword: Homage to Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 1, 2 (1979).

- Babette Deutsch, “Profiles: The Cloister and the Bench,” New Yorker, March 22, 1930, at 28.

- 217 N.Y. 382 (1916).

- Cardozo’s intimate familiarity with Court of Appeals procedures and personnel unquestionably facilitated his transition from the trial bar to the Court. Additionally, the Court at the time had a heavy commercial docket, which had been the essence of his law practice.

- Benjamin N. Cardozo, Jurisdiction of the Court of Appeals 11 (2d ed. 1909).

- Professor Kaufman noted (at 446-447): “As a working judge, Cardozo avoided large questions of doctrine most of the time. It was hard enough to get agreement in the court on a difficult case within the short time in which he and his colleagues had to decide it before moving on to the next one. . . . Sometimes it was apparent that he was unsure how he would decide the next relevant case, didn’t want to commit himself in advance, and therefore was careful to explain the current case in a way that left himself and court flexibility for the next one. Cardozo’s candor consisted in trying to explain the present result without encumbering the future. It was a difficult job, and on the whole, he did it well.”

- Only Judges Frank Hiscock, Emory Chase and William Cuddeback joined in Cardozo’s opinion. Judge John Hogan concurred only in the result, Chief Judge Bartlett dissented and Judge Cuthbert Pound did not vote at all.

- Starting with an 1852 case, Thomas v. Winchester, that had carved an exception to Winterbottom to create liability to a remote purchaser of a falsely labeled poison, Cardozo then traced the application of Thomas to a widening array of products: collapsing scaffolds, exploding coffee urns, bursting soda bottles. The “principle” of Thomas grows with each application, until the exceptionCskillfully generalizedCswallows the rule.

- 217 N.Y. at 391.

- 217 N.Y. at 390.

- Karl Llewellyn, The Common Law Tradition: Deciding Appeals 434 (1960). Llewellyn called Cardozo’s opinion a masterpiece.

- Richard A. Posner, Cardozo: A Study in Reputation 109 (1990) [hereinafter “Posner”]. MacPherson not only settled the law here but also after a time settled the law for the House of Lords. McAlister v. Stevenson,[1932] All E.R. Rep. 1, [1932] A.C. 562.

- Donald MacPherson had bought his vehicle from a car dealership in Schenectady, not from the defendant Buick Motor Company.

- 249 N.Y. 458, 464 (1928).

- See Irving Lehman, “The Influence of Judge Cardozo on the Common Law,” in Association of the Bar of the City of New York, 1 The Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lectures 15, 25 (1995).

- Nicholas L. Georgakopoulos, “Meinhard v. Salmon and the Economics of Honor,” 1999 Colum. Bus. L. Rev. 137 (1999).

- Kaufman 248.

- Kaufman 359.

- Posner 13; G. Edward White, Tort Law in America 123 (1980).

- Benjamin N. Cardozo, The Growth of the Law (1924), reprinted in Selected Writings 186, 225.

- Benjamin N. Cardozo, Law and Literature (1925), reprinted in Selected Writings 339, 352.

- Id. at 352.

- Kaufman quotes Jerome Frank’s anonymously published view that Cardozo’s style was “awkward” and “sometimes ornate, baroque, rococo”; his ornaments at times “annoyingly functionless” and his metaphors “elaborate.” Kaufman 448-449. On the other side, another Cardozo contemporary, Professor Zechariah Chafee, opined that “Cardozo possesses one of the best prose styles of our times.” Id. at 449.

- Id. at 449-450.

- Coler v. Corn Exchange Bank, 250 N.Y. 136, 141 (1928).

- Schloendorff v New York Hospital, 211 N.Y. 125, 127 (1914). Since this was among Cardozo’s very first opinions, plainly he brought this literary technique to the bench with him. As Chief Judge Lehman noted in his first Cardozo Memorial Lecture, “every student of the law has recognized that judges who phrase their opinions with artistry have at times persuaded great courts and even themselves, where reason, unadorned, might have pointed to a safer path.” Irving Lehman, “The Influence of Judge Cardozo on the Common Law,” in 1Association of the Bar of the City of New York, The Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lectures 1941-1995 15, 19-20 (1995).

- Benjamin N. Cardozo, Law and Literature (1925), reprinted in Selected Writings 341 (“There is an accuracy that defeats itself by the overemphasis of details. . . The picture cannot be painted if the significant and the insignificant are given equal prominence. One must know how to select”).

- Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon, 222 N.Y. 88, 90 (1917).

- Palsgraf v. Long Island RR Co., 248 N.Y. 339 (1928).

- Jacob & Youngs, Inc. v. Kent, 230 N.Y.2d 239, 240 (1921).

- Kaufman 270, 287.

- Kaufman 204 (quoting Arthur L. Corbin, The Judicial Process Revisited: Introduction, 71 Yale L. J. 195, 197-98 (1961)).

- Id. Corbin mentions Cardozo’s eyes, hair and smile, but curiously notCas one might expect after a two-hour readingChis voice. Kaufman reports that after hearing a tape of Cardozo at a celebratory dinner: “I was blown away. I might have been listening to William Jennings Bryan himself. Cardozo was an orator, in the style of the 19th century. In one minute, I had learned why he was a captivating speaker, and I understood a good deal more about his success at the bar. I also ended up rewriting portions of the book.” Andrew Kaufman, Adventures of a Biographer: Professor Kaufman Recounts his Forty-Year Pursuit of Cardozo, Harv. L. Bull. 9-10 (Summer 1998).

- Professor Gilmore put it more starkly: “Cardozo’s hesitant confession that judges were, on rare occasions, more than simple automata, that they made law instead of merely declaring it, was widely regarded as a legal version of hardcore pornography.” Grant Gilmore, The Ages of American Law 77 (1974). Cardozo initially resisted publication of his manuscript by the Yale Press, protesting that “if it were published, I would be impeached.” Corbin, supra note 77, at 198.

- See Kaufman 200-203 (discussing Oliver Wendell Holmes, John Chipman Gray and Roscoe Pound).

- Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process 20 (1921) [hereinafter Judicial Process].

- Id. at 30-31.

- Id. at 83.

- Id. at 89.

- Paul A. Freund, “Foreword: Homage to Mr. Justice Cardozo,” 1 Cardozo L. Rev. 1, 3-4 (1979) (quoting Justice Frankfurter). It is unlikely that Frankfurter thought the process of deciding cases could be reduced to a formula. “Whenever Frankfurter was asked how he weighed the elements of history, precedent, custom and social utility in reaching a decision, he was likely to reply, ‘When Velazquez was asked how he mixed his paints, he answered, “With taste.”‘” Id. at 4.

- Ten years after the Storrs Lectures, Cardozo gave an address specifically distancing himself from the more radical Legal Realists who “exaggerate[d] the indeterminacy, the entropy, the margin of error, [and] treat[ed] the random or chance element as a good in itself and a good exceeding in value the elements of certainty and order and rational coherence. . . .” Benjamin N. Cardozo, Jurisprudence, reprinted in Selected Writings 7, 30. Cardozo’s address infuriated Jerome Frank, who expressed his views in a sizzling 31-page letter, complete with a 31-page appendix. Kaufman 460-61.

- “Insignificant is the power of innovation of any judge, when compared with the bulk and pressure of the rules that hedge him on every side. . . . All that the method of sociology demands is that within this narrow range of choice he shall search for social justice.” Judicial Process 136-37.

- “One of the most fundamental social interests is that law shall be uniform and impartial . . . Therefore in the main there shall be adherence to precedent.” Id. at 112.

- Id. at 113. See also Judith S. Kaye, The Human Dimension in Appellate Judging: A Brief Reflection on a Timeless Concern, 73 Cornell L. Rev. 1004, 1015 (1988).

- Hynes v. N.Y. Cent. R.R., 231 N.Y. 229, 235 (1921).

- Jacob & Youngs, Inc. v. Kent, 230 N.Y. 239, 242 (1921).

- See, e.g., Hynes, 231 N.Y. at 236 (“We think that considerations of analogy, of convenience, of policy, and of justice, exclude [plaintiff] from the field of the defendant’s immunity . . . “); People ex rel. Karlin v. Culkin, 248 N.Y. 465, 477 (1928)(“The argument from history is reinforced by others from analogy and policy”).

- As Kaufman observes (at 359): “when it came to enforcing promises in the commercial context, he looked to contemporary commercial practice for enlightenment. When it came to enforcing promises relating to marriage or charitable subscriptions, he relied heavily on general social preferences or specific governmental policies.”

- Gilmore, The Ages of American Law at 77.

- In Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319 (1937), for example, he employed an issue-by-issue approach on incorporation of the Bill of Rights into the Fourteenth Amendment, concluding that the right in questionCthe Fifth Amendment’s immunity from double jeopardyCwas not “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty” and thus not binding upon the States. His view was overruled decades later in Benton v. Maryland, 395 U.S. 784 (1969).

- Cardozo voted-in majority or dissent-to sustain a wide range of state and federal regulatory efforts. See Kaufman 491-533. But Cardozo also voted to strike down such efforts when he concluded that reasonable limits had been exceeded. See e.g., Kaufman 503-504, 511-512.

- Kaufman 200.

- See Irving Lehman, “The Influence of Judge Cardozo on the Common Law,” in 1 Association of the Bar of the City of New York, The Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lectures 15, 17 (1995).

- Cardozo himself thought his greatest contribution was his work in New York. He wrote that in Albany he “really accomplish[ed] something that gave a new direction to the law,” but in Washington he had to be satisfied if he “accomplished something by his vote.” Kaufman 493. The brevity of Cardozo’s service on the Supreme Court limited his impact, although some believe that he did well with the time he had. See Richard Friedman, “On Cardozo and Reputation: Legendary Judge, Underrated Justice?,” 12 Cardozo L. Rev. 1923, 1932 (1991) (“Cardozo’s was one of the greatest short tenures on the Court in its history . . . .”).

- Judicial Process 178.

- Posner, chapter 5.

- Guido Calabresi, A Common Law for the Age of Statutes 1 (1982).

- See generally Judith S. Kaye, State Courts at the Dawn of a New Century: Common Law Courts Reading Statutes and Constitutions, 70 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1 (1995).

- 250 N.Y. 479 (1929).

- Morgan v. New York, 90 N.Y.2d 471 (1997).

- 247 N.Y. 160 (1928).

- Strauss v. Belle Realty, 65 N.Y.2d 399 (1985); see also Church v. Callanan Industries, Inc., 99 N.Y.2d 104 (2002).

- 213 N.Y. 240, 243 (1914); see People v. Aiken, 4 N.Y.3d 324 (2005); People v. Jones, 3 N.Y.3d 491 (2004); People v. Hernandez, 98 N.Y.2d 175 (2002).

- 248 N.Y. 465, 478 (1928); see Anonymous v. Bureau of Professional Medical Conduct/State Bd. for Professional Medical Conduct, 2 N.Y.3d 663 (2004).

- 227 N.Y. 468, 469 (1920) (observing the revival of “smouldering fires of an ancient judicial controversy”).

- See Banque Indosuez v. Sopwith Holdings Corp, 98 N.Y.2d 34 (2002).

- 245 N.Y. 1, 5-6 (1927).

- See Spodek v. Park Property Development Assoc., 96 N.Y.2d 577 (2001).

- East End Trust Co. v. Otten, 255 N.Y. 283, 286 (1931), quoted in Matter of Francois v. Dolan, 95 N.Y.2d 33 (2000).

- People ex rel. Alpha Portland Cement Co. v Knapp, 230 NY 48, 60 (1920); quoted in CWM Chemical Services v Roth, 5 N.Y.3d __(March _ 2006 [NED]).

- Glanzer v. Shepard, 233 N.Y. 236 (1922).

- Ultramares Corp. v. Touche, 255 N.Y. 150 (1930).

- Ossining Union Free Sch. Dist. v. Anderson, 73 N.Y.2d 417 (1989).

- Credit Alliance Corp. v. Arthur Andersen & Co., 65 N.Y.2d 536 (1985).

- Palka v. Servicemaster Management, 83 N.Y.2d 79 (1994).

- 211 N.Y. 125 (1914).

- 2 N.Y.2d 656 (1957).

- 367 U.S. 643, 659 (1961).

- 242 N.Y. 13 (1926).

- Kaufman reports (at 204) that between 1960 and 1994, The Nature of the Judicial Process sold 156,637 copiesCmore than six times as many as during its first 39 years. Posner reports (at 20) that between 1966 and 1988, the book was cited an average of 28.4 times a year in journals tabulated by the Social Sciences Citation Index-making it the third most often cited pre-1960 work of jurisprudence (trailing only Holmes’s The Common Law and “The Path of the Law”).

- That debate began with the birth of the judicial branch. See William J. Brennan, Jr., Reason, Passion and “The Progress of the Law,” in 3 Association of the Bar of the City of New York, The Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lectures 1439 (1995).

- Judicial Process 141.

- Irving Lehman, Benjamin Nathan Cardozo: A Memorial 8 (1938).

- The number of articles about Cardozo’s life and jurisprudence is simply huge. This list represents only a small sampling. No compilation would be complete, however, without reference to the Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lectures, an esteemed annual lecture delivered at the City Bar Association in New York City. The Lectures were instituted in 1941, just three years after Cardozo’s death, the first — “The Influence of Judge Cardozo on the Common Law” — delivered by his close friend Chief Judge Irving Lehman. Forty-seven of those lectures, many dealing with Cardozo’s work and influence, were published in three volumes by the City Bar in 1995; several of the lectures (both before and since 1995) have been published in law reviews.