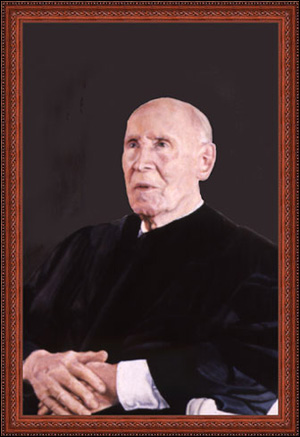

Adrian Burke was a tall, broad shouldered, imposing man with a ruddy Irish face and piercing blue eyes that often twinkled with humor, especially when he was telling an anecdote about the foibles of some dignified public figure. His respect for the law derived from a religious conviction that while mankind had an appetite for the good, it also had a tragic attraction to evil, which the law must control. He had no illusions of human perfectibility and was seldom shocked by human weakness. Outside of court he was not inclined to be severely judgmental. Of some corrupt official he would merely say something like, “Yes, he was a difficult person.” Worldly tolerance, however, had no place when he felt that the powerful were inflicting some harm upon the weak, especially children. For example, when the Court found a statute prohibiting the sale of sexually explicit material to children to be unconstitutionally vague, Judge Burke”s dissent used strong language in criticizing the majority, and concluded tartly that “The juvenile market has been made safe from Fanny Hill” et al.”1

Adrian Paul Burke was born in New York City on October 2, 1904, and on September 3, 2000, died at his home in Lauderhill, Florida, where he is buried. In referring to his place of birth, Judge Burke often spoke of the “golden age” of New York City. His family had roots in the city tracing back to the early 19th century, and he possessed intimate knowledge of its parks, neighborhoods, people, politics, and cultural history. His father was a deputy sheriff of New York County, and young Adrian came to know the leading political characters of the day. For example, he thought highly of Charles F. Murphy, the leader of Tammany Hall. In a memoir, he wrote: “No one called him Charlie; he was Mr. Murphy to all. . . .When Murphy died the saying was ‘the brain of Tammany Hall is buried in Calvary Cemetery.’ His successors lacked Murphy’s broad vision. The city deteriorated.”2 Burke believed that it took the genius of Fiorello LaGuardia to put the city back on its feet.

Adrian Burke’s intellect and temperament led him to Regis High School, Holy Cross College, and Fordham Law School. His father’s death made it necessary for young Adrian to earn money, so he taught at Regis High School for three years while attending Fordham Law School at night. After passing the bar, he began law practice with an emphasis on real estate law and management, a specialty he had learned while working summers in a real estate office. He married his wife, Edith, in 1934.

Adrian Burke’s family connections led to his nomination and election as the second youngest delegate to the state constitutional convention in 1938. There he met and learned lessons in public service from the likes of Alfred E. Smith, Herbert Lehman, Senator Robert F. Wagner, Robert Moses, and Chief Judge Crane. His assignment to the social welfare committee was the start of a lifelong devotion to child welfare. He was proud of his role in supporting the adoption of a unique amendment to the state constitution introduced at the behest of Mayor La Guardia: “The aid, care and support of the needy are public concerns and shall be provided by the state.” No comparable guarantee appears in the United States Constitution.

District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey appointed Burke to the New York County youth council bureau, and later, when governor, to the New York Board of Social Welfare. Burke’s work in the constitutional convention and in social welfare led to an acquaintance with Robert F. Wagner Jr. Although Burke had never been a political insider, his public service gained him insight into the political scene and he advised Wagner to run for Mayor in 1953. Wagner agreed only if Burke would manage his campaign. Wagner won and appointed Burke to be Corporation Counsel in 1954.3 One year later, Burke ran for the Court of Appeals on a ticket headed by Averill Harriman. Both were elected. Judge Burke enjoyed recalling that he received more votes than the governor.

Judge Burke’s view of the moral roots of law and his concern for children came together in his dissent in Byrn v. New York Health & Hospitals Corp.4 This was a case prior to Roe v. Wade5 in which a state statute legalized specified abortions that had previously been outlawed. The majority candidly acknowledged that current scientific knowledge classified the unborn fetus as “human” and “unquestionably alive,” with an autonomous development separate from the mother although dependent upon her. The Court nevertheless held that the degree of legal recognition was a policy question to be decided by the legislature. Judge Burke’s dissent roundly rejected what he considered a purely positivist philosophy that a creature in fact human could be made legally non-human by legislative fiat. Insisting that the basic rights of man were antecedent to the state, not conferred by it, he contrasted the natural law tradition embodied in the Declaration of Independence to the barbarous systems of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. His impassioned appeal was rejected by his associates, and has become even more obsolete in light of Roe v. Wade, which largely takes the issue out of the legislative arena.6 Both Judge Burke and the justices of the United States Supreme Court were willing to exercise judicial authority to overturn legislative action on opposite sides of the abortion issue.

Although Judge Burke’s strong feelings could be bluntly expressed in a few controversial cases, he was naturally ebullient and his relations with his associates were invariably cordial. A law clerk recalls questioning a sudden increase in the number of applications for leave in criminal cases made in his New York City chambers on 42nd Street, and even more astonishing, an uncharacteristic liberality in granting them. The Judge replied, “most of these would ordinarily go to Judge Fuld (on 44th Street), but he’s away in Switzerland now so they have to come to me. I feel I should treat them the same way Stanley would have done.” Judge Burke’s wit and amiability endeared him to all who worked with and for him, and were prominently featured in the remarks of his colleagues upon his retirement.

Although generally conservative on issues of criminal law and procedure, Judge Burke’s concern for the dignity of the human person is apparent in his opinion for the majority in Fenster v. Leary,7 striking down a vagrancy statute because it punished conduct that in no way impinged on the rights or interests of others. The harsh “dual sovereignty” limitation on the rule against double jeopardy was mitigated by his expansive interpretation of a New York statute precluding double jeopardy based on a prior judgment in “another state or country.” The statute was held applicable to a prior acquittal in federal court.8

In his 19 years of service on the Court, Judge Burke wrote 252 signed opinions for the Court and 146 concurring or dissenting opinions. A typical Burke opinion attended closely to the facts of the case. Once the facts were clear, the law seemed to follow naturally in a common sense way.

Judge Burke’s style of judging can be seen in a leading case involving the effect of written disclaimers raised as a defense to fraud actions. In 1957, he had joined in Judge Fuld’s opinion for the court rejecting an attempt to screen fraudulent conduct by a written contractual disclaimer.9 Two years later, when the issue arose in a different context, the two jurists found themselves on opposite sides. In Danann Realty v. Harris,10 the purchaser of an apartment building sought to charge the seller with fraud in misrepresenting the building”s operating expenses. The defense was that the written contract of sale expressly disclaimed reliance on oral representations on several topics, including “expenses.” The trial court dismissed the complaint, and the issue on appeal was whether the earlier case mandated a trial in all cases, without any exceptions based on the particulars of a given situation. In dissent, Judge Fuld insisted that under no circumstances should dishonesty be allowed to hide behind a piece of paper. Judge Burke, however, carried the rest of the judges with him in distinguishing the earlier case. The specificity of the disclaimer and the sophistication of the parties established as a matter of law that there could have been no reasonable reliance on any oral misrepresentation. The security of the written contract was preserved. Judge Fuld’s position had the merit of consistent adherence to a high moral principle: no exceptions. Judge Burke’s position left room to distinguish between knowledgeable business people carefully drafting a contract tailored to their desires, and an unsophisticated consumer duped by terms in a form contract not carefully examined or understood.

Judge Burke was not particularly receptive to highly theoretical writing found in the pages of legal journals; the way the law was developed in prior cases was usually sufficient for his judgment. For example, his dissent in Seider v. Roth11 opposed the Court”s adoption of a novel theory of quasi-in-rem jurisdiction through attachment of a nonresident defendant”s insurance policy. This dissent was later vindicated when the United States Supreme Court found the procedure unconstitutional. However, Judge Burke was by no means wedded to the past. When careful scholarship exposed the injustice of an outmoded precedent, he was willing to listen, as demonstrated by his opinion in Battalla v. State of New York,12 allowing a tort action for mental injury from fright negligently caused, but without proximate physical injury. Judge Burke arrived at this conclusion only after respectfully examining the reasons given in the leading 19th century case13 and finding them unpersuasive. A similar careful balancing of policy considerations appears in Gelbman v. Gelbman,14 in which both scholarly criticism and judicial developments in other states led to discarding an old rule disallowing intra-family tort actions.

Of course, not all cases generate controversy or attract public interest. There are many obscure or technical issues that are nevertheless of importance to lawyers and judges. Judge Burke wrote several such opinions that law professors found of sufficient importance to include in casebooks studied by thousands of law students. Menzel v. List,15 addressing the measure of damages for breach of warranty of title, is an important contribution to the tangle of problems surrounding stolen art works. Intercontinental Hotels Corp v. Golden16 explores the effect of public policy on the recognition of foreign judgments. A difficult procedural issue incident to the merger of law and equity is examined in light of history in I.H.P. Corp. v. 210 Central Park So. Corp.17 And the excuse of conditions in contract law is fully analyzed in Cohen v. Kranz.18

Toward the end of his life, Judge Burke wrote a memoir, edited and privately published by his youngest son, Frank. It is entitled Everything I Needed, and concludes:

Success is often a combination of chance and purpose, timing and initiative, plus the often unanticipated intervention of others. More often than not, it comes from receiving not what we actively seek and want but what we unknowingly require. I count myself fortunate that chance, divine providence, and the bountiful life of New York City gave me, in generous measure, everything I needed.

Progeny

Judge Burke’s wife, Edith, died in 1995. They had three children. Two sons survive: Adrian Burke Jr. of Las Vegas and Francis Burke of Kingston, Ontario. A daughter, Edith Burke De Muth, died in 2002. Judge Burke’s grandchildren are: Maureen Burke of New Haven, CT; Michelle Burke of Berkeley, CA; Adrian P. Burke III of Grosse Point, MI; Andrew De Muth of Freehold, N.J.; William De Muth of Freehold, NJ; Christopher De Muth of Freehold, NJ; Joseph De Muth of Jackson, NJ; Adrianne De Muth of Tinton Falls, NJ; Wylie Burke of Toronto, ON; Tyler Clark Burke of Toronto, ON; and Gabriel Burke-Burfoot of Kingston, ON.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

1 Cath. Law. 68 (1955).

Beame, Tribute to Judge Burke, 48 St. John”s L. Rev. 438 (1974).

Breitel, Tribute to Judge Burke, 48 St. John”s L. Rev. 435 (1974).

Congratulatory Citation on the occasion of Adrian Burke”s 90th birthday, from Governor Mario Cuomo (formerly a law clerk to Judge Burke).

Desmond, Tribute toi Judge Burke, 48 St. John”s L. Rev. 437 (1974).

Gegan, Tribute to Judge Burke, 48 St. John”s L. Rev. 439 (1974).

In Memoriam, 95 N.Y.2d xix. (2000).

Obituary, September 9, 2000, New York Times, Section B, page 8.

Remarks of Judges Stanley Fuld and Charles Breitel on the occasion of Judge Burke”s retirement in volume 33 N.Y.2d. ix.

Publications

Everything I Needed: Living and Working in New York (F. Burke ed. 1996).

Tribute to Chief Judge Fuld, 71 Colum. L. Rev. 542 (1971).

Tribute to Judge Keating, 86 Brooklyn L. Rev. 1 (1969).

Tribute to Chief Judge Desmond, 42 St. John”s L. Rev. 9 (1967-68).

Book Review (F. A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty), 29 Ford. L. Rev. 410 (1960-61).

Endnotes

- People v. Bookcase, Inc., 14 N.Y.2d 409, 419 (1964).

- Adrian Burke, Everything I Needed: Living and Working in New York, 11 (F. Burke ed. 1996).

- After nineteen years on the Court, Judge Burke retired one year before the constitutionally mandated age limit of 70 in order to once again head the office of corporation counsel in Mayor Beame”s administration.

- 31 N.Y.2d 194 (1972).

- 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- In contrast, recent legal developments demonstrate the continuing vitality of Judge Burke”s dissent from the decision in Endresz v. Friedberg, 24 N.Y.2d 478 (1969), denying a tort remedy to a fetus who died from its injuries in utero.

- 20 N.Y.2d 309 (1967).

- People v. LoCicero, 14 N.Y.2d 374 (1964).

- Sabo v. Delman, 3 N.Y.2d 155 (1957).

- 5 N.Y.2d 317 (1959).

- 17 N.Y.2d 111 (1966).

- 10 N.Y.2d 237 (1961).

- Mitchell v. Rochester Ry. Co., 151 N.Y. 107 (1896).

- 23 N.Y.2d 434 (1969). The opinion contains an interesting observation on the roles on the judiciary and the legislature in updating outmoded precedent. The old rule originated in Sorrentino v. Sorrentino, 248 N.Y. 626 (1928) and had been reaffirmed in a case in which Judge Burke concurred shortly after coming on the Court. Badigian v. Badigian, 9 N.Y.2d 472 (1961).

- 24 N.,Y.2d 91 (1969).

- 15 N.Y.2d 9 (1964). Judge Burke”s foray into choice of law in Dym v. Gordon, 16 N.Y.2d 120 (1965) did not long survive. See Tooker v. Lopez, 24 N.Y.2d 569 (1969).

- 12 N.Y.2d 329 (1963).

- 12 N.Y.2d 242 (1963).