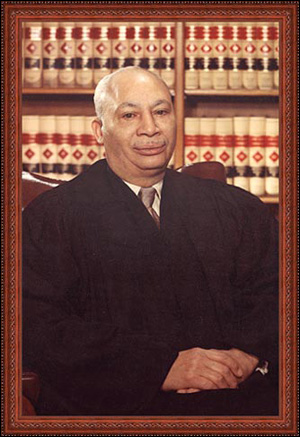

In 1926, an African-American woman and her two brothers, accused of killing a Sheriff, were dragged from a South Carolina jail and towed behind a car to an area where a thousand people stood to watch as they were shot and mutilated to death. Local authorities, including the jailer and deputy sheriff, brazenly participated in the incident known as the “Lowman lynchings.”1 However, no one was ever prosecuted for the deaths, and many in the local community — among them Harold Arnoldus Stevens — were deeply affected. In college at the time, Stevens then became determined to be a part of the legal system and use it as a tool to eliminate such injustice. “He said the incident ‘cemented’ a determination already formed while in high school to become a lawyer.'”2 In a 1958 interview, Judge Stevens explained “I was inspired to study law because it was our best bet to eliminate things like this.”3 Throughout his many years of legal service, Judge Stevens remained vigilant in his fight against persecution and prejudice. He celebrated a life of many firsts, including becoming the first African-American Judge to sit on the New York State Court of Appeals in its 128-year history.

Judge Harold Arnoldus Stevens was born on October 19, 1907 on a farm of approximately 1,000 acres on John’s Island, South Carolina. The farm was owned by Judge Stevens’ father, William F. Stevens, a blacksmith, and his grandfather, Quash Stevens, a former slave and wealthy planter.4 Quash was the son of the island’s owner and slave holder, Elias Vanderhorst,5 whose brother Arnoldus Vanderhorst IV held Quash as a slave. After acquiring freedom, however, Quash remained loyal to the Vanderhorst family. Judge Stevens, who spent some of his early years with Quash, was given the middle name Arnoldus, common to the Vandorhorsts.

Judge Stevens’ mother, Lilla Johnson Stevens, was a school teacher. The youngest of four boys, Stevens lived on John’s Island with his parents and grandfather until the age of three. After his father died, Stevens’ mother moved the family to Columbia, South Carolina where they lived with his maternal grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. James H. Johnson. Judge Stevens described his mother and grandfather James, a minister turned business man, as the greatest influences in his life. Johnson “schooled him in the love of poetry, music, history and biography.”6 Judge Stevens’ mother eventually remarried to the Reverend John D. Whitaker.

Stevens attended Claflin College High School in South Carolina and, in 1930, earned an A.B. from Benedict College, in Columbia, South Carolina. Unable to attend law school in the then-segregated South, Stevens moved to Boston, where he attended Boston College School of Law and was vice president of his class. In 1936, Stevens became the first African-American and the first non-Catholic to graduate from the law school, earning an LL.B. degree in labor law. Shortly after graduation, he converted to Roman Catholicism which would come to play a major role in this life. Stevens was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar in 1936, the New York State Bar in 1938, and the South Carolina Bar in 1940. He received admission to practice in the Federal Courts and the United States Supreme Court.

Around 1938, Stevens moved to New York where he started his legal career as a clerk in the law offices of Harlem Assemblyman William T. Andrews. Andrews offered Stevens a junior partnership, and Stevens developed himself into an expert in labor law. He represented the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the Brotherhood of Colored Locomotive Firemen.7 Stevens remained in private practice until 1950; he was a partner in Dyett & Stevens (1942-1948) and Brandenburg & Stevens (1948-1950). Around the same time, from 1938 to 1942 and 1947 to 1950, Stevens served as a labor law instructor at the Association of Catholic Trade Unionist.

On Christmas Day, 1938, Stevens returned to South Carolina to marry Ella Clyde Myers, whom he had known since grade school and, like him, had attended Benedict College.8 The couple moved to Manhattan, “for he had fallen in love with the city.”9 In a New York Times interview, Judge Stevens recalled “a long, hectic trip South . . . to deal with the problems of Negro sleeping car porters, and the relief and joy he felt when, returning at night across the jersey meadows, he saw the twinkling panorama of city lights. ‘I can’t imagine living anywhere else,'” he said.10 Judge Stevens and Ella did not have any children, and settled in Harlem where they engaged in various religious, social, and charitable activities.

After President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802 (June 25, 1941), which prohibited government contractors from engaging in employment discrimination based on race, color or national origin, Stevens was an appointed member of the President’s Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC). He also served on the provisional committee to organize black locomotive firemen. In 1943, Stevens resigned from the FEPC in protest to an order by the chairman of the War Manpower Commission indefinitely postponing hearings on complaints of discrimination against African-American firemen and brakemen on railroads. In his resignation letter, Stevens called the order “a blow to the Negro railroad workers who looked to your committee for some solution or adjustment to their problems. . . .”11 Stevens wrote “[t]he fight for democracy and justice, like charity, must begin at home.”12 That same year, he enlisted in the then-segregated United States Army. He served as a Buffalo Soldier at West Point, and was a World War II veteran.13

In 1945, Stevens was a member of the voluntary legal panel of the Workers Defense League. On behalf of the labor group, he filed an amici curiae brief in the United States Supreme Court case Morgan v. Virginia (38 US 373 [1946]), involving a challenge to racial segregation on buses. Morgan involved the constitutionality of a Virginia statute that made it a misdemeanor for passenger motor vehicle carriers to allow black and white passengers to occupy adjacent seats. The statute required the driver or other person in charge of the vehicle “to increase or decrease the space allotted to the respective races as [was] necessary or proper.”14 Drivers could direct passengers to change their seats to accommodate the statute’s separation requirement.

Irene Morgan, a young African-American woman, defied a driver’s order to surrender her seat on a bus traveling from Virginia to Maryland. She was arrested and fined ten dollars for violating the Virginia statute. William H. Hastie and Thurgood Marshall argued on her behalf that the statute burdened interstate commerce. As amicus Stevens addressed two main points: (1) that the Virginia statute violated Article I, section 8 of the United States Constitution and as such was inherently burdensome on interstate commerce and (2) that the statute was inconsistent with the Articles 55-c and 56 of the United Nations Charter.15 In a landmark decision, the Supreme Court agreed that segregation on interstate transportation violated the Commerce Clause of the Federal Constitution.16 This victory confirmed Judge Stevens’ conviction that the best way to eliminate racial injustice was through the law.

In 1946, Stevens was elected to the New York State Assembly from the then predominantly white Thirteenth Assembly District in Washington Heights (New York County). He won the seat over three rivals. Assemblyman Stevens served until 1950 when he was elected to the Court of General Sessions, a position he held from 1951 to 1955.

In 1955, Governor W. Averell Harriman appointed him Justice of the New York State Supreme Court. He was elected for a 14-year term in November of that year, and reelected in 1969 with the endorsement of all four major parties. Harold Stevens was the first African-American to become successively a judge of the Court of General Sessions and a Justice of the State Supreme Court.

Effective January 1, 1958, Governor Harriman designated Judge Stevens Associate Justice of the Appellate Division, First Department. Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller later reappointed him associate justice in 1963 and 1968. Around that time, Justice Stevens said “The law is my life. I love it.”17 He said that “[t]here is poetry and drama in the law . . . It never grows stale. Every case is a human story. A tragedy for some, a triumph for others.”18 This sensitivity and compassion paired with his intelligence made Judge Stevens a well-respected and exceptional jurist among his contemporaries.

On January 1, 1969, Governor Rockefeller designated Harold Stevens the presiding justice of the Appellate Division, First Department, the first African-American to hold such a position. When reminded of this fact in an interview, Judge Stevens said “it seems to me that color is incidental. . . . I’m aware this appointment is breaking new ground. I recognize that fact, and I’m grateful for the opportunity. But color does not restrict or inhibit the performance of my legal duties.”19 At that time, Judge Stevens was the highest ranking African-American in any state judicial system.

As Presiding Justice, Judge Stevens helped decide Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York (50 AD2d 265 [1975]), which ordered the preservation of New York’s Grand Central Terminal as a City landmark. He is remembered for “presid[ing] as a highly respected legal scholar who never failed to consider the human dimension of the law.”20 Judge Stevens served as Presiding Justice from 1969 until 1974. He is credited with creating “sentencing panels” to review cases in effort to avoid sentencing disparities that often reflected differences in race and economic status.

In 1974, Governor Malcolm Wilson appointed Judge Stevens to the Court of Appeals for an interim term. He was the first African-American to sit on the Court in its 128-year history.

In his single year on the bench, Judge Stevens wrote one of the Court’s most notable opinions in the area of administrative law, Matter of Pell v. Bd. of Educ. (34 NY2d 222 [1974]). The case set forth the standard of judicial review in CPLR article 78 proceedings and has been cited over 2,500 times in legal decisions, treatises, and journals. While on the Court, Judge Stevens was characterized as a “‘swing’ vote, often siding with a conservative majority.” He said of himself: “I don’t know exactly how to characterize my philosophy. . . . I’m not a total conservative. On the other hand, I’m not a total radical.”21

Whatever his philosophy, Judge Stevens was known as “an exceptional jurist and a treasured friend” to those who shared the bench with him.22 Former Chief Sol Wachtler said, “Harold Stevens brought warmth and humor to this Court, and these are qualities that all of us who knew and respected him will always remember fondly. More importantly, however, Harold also possessed a deep understanding of the human condition, an understanding which found its way into his decisions,” adding that “his intelligence and love for the law challenged us to be better Judges; his wisdom and understanding challenged us to be better human beings.”23

At the time of Judge Stevens’ interim appointment, full term Judges were elected to the Court of Appeals. Therefore, during his time on the bench, Judge Stevens was concerned with presiding over cases as well as running a campaign. He ran against two other candidates in the Democratic primaries — Appellate Division Justice Lawrence H. Cooke and attorney Jacob D. Fuchsberg. Having served 24 years as a judge, including five as Presiding Justice, Judge Stevens ran on the slogan “Keep an Able and Experienced Judge on the Court of Appeals.”24 Judge Cooke was also a long time veteran of the court system, having served on four courts including the Appellate Division, Third Department.25

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York gave its highest rating to Judge Stevens, finding him “highly qualified and preferred.”26 The City Bar Association also found Judge Cooke “highly qualified,” but did not approve Fuchsberg in a critical commentary of the candidate.27 The Liberal, Conservative, and Republican parties all backed Judge Stevens, and the Liberal party endorsed Judge Cooke. Given these endorsements, Judges Stevens and Cooke were each assured spots on the November ballot. Fuchsberg gained his position on the ballot winning the Democratic primary, creating a five-way race for the two vacancies on the Court. Louis M. Greenblott, an Associate Justice of the Appellate Division, Third Department, and Henry S. Middendorf Jr., a Manhattan lawyer, were the other two candidates.

Despite appearing as a favorite, Judge Stevens lost the election to Judge Cooke and Jacob Fuchsberg. Judge Cooke received more votes than both Stevens and Fuchsberg, and was declared a winner of one of the two seats with only three-quarters of the election districts counted. Fuchsberg finished second, and Judge Stevens third. Judge Stevens conceded the loss “after results from 94 per cent of the state’s polling places showed Mr. Fuchsberg ahead of him by 81,133 votes.”28 Following the election, Judge Stevens was redesignated Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, First Department.

His defeat at the polls fueled an already existing debate concerning whether Judges of the Court of Appeals should be appointed or elected. In 1977, along with other major reforms, the 1846 constitutional provision requiring that the Judges of the Court be elected was repealed. The Amendment provided for the Governor to appoint the Judges of the Court, with the advice and consent of the New York State Senate, from a list of names recommended by the Commission on Judicial Nomination.29

Justice Stevens retired in 1977 at age 69 and, on November 9, 1990, died in his home of a heart attack. He was 83. Upon his death, his papers were donated to The New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Judge Stevens lived across the street from the center and maintained close ties to his community.

Early in his judicial career, Judge Stevens received the Papal Award Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice for his social work involving interracial relations. His board memberships included: the Catholic Interracial Council of New York; Citizens Planning Council; Catholic Club; Catholic Youth Organization; Grand Street Boys Association; and the Board of Governors of the Guild of Catholic Lawyers. Judge Stevens was president of the Catholic Interracial Council of New York, and a committee member of the New York County Lawyers Association. He was a lifetime member of the NAACP and, in 1996, was enshrined in the South Carolina Black Hall of Fame.

Judge Stevens received many honorary degrees as doctor of laws, including one from Benedict College, South Carolina. At that commencement, he reminded graduates “of their ‘responsibility to wipe out inequities,'”30 a responsibility he took very seriously and remained committed to his entire life. He said to the students that “[t]he American system, even with its imperfections, is the best system in the world and affords the best opportunity. . . . Its weaknesses are in the failures of application and the barriers of applications.”31 These words are in keeping with the promise Judge Stevens made to himself in 1926 — to become a part of the legal system so that he could help eliminate the injustice of prejudice in a time of Jim Crow laws and beyond.

Progeny

Judge Stevens was survived by his wife, Ella C. Myers Stevens, who died on November 3, 2003 at the age of 95. The couple had no children. He was also survived by one of his brothers, John Stevens of New York City, and several nieces and nephews.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Arnesen, Brotherhoods of Color: Black Railroad Workers and the Struggle for Equality, (Dec. 2000).

Asbury, Fuchsberg Wins Appeals Contest: 96% Tally Shows He Beat Stevens by 81,133 Votes, N.Y. Times, Nov. 8, 1974, at 82.

BellSouth South Carolina African-American History Online, November 1991 Featured Honoree: The Honorable Harold A. Stevens,

www.scafricanamericanhistory.com /currenthonoree_print.asp?month=11&year=1991

Bench and Politics, N.Y. Times, Nov. 8, 1974, at 38.

Goldstein, 3 Candidates for Court of Appeals Find Experience is Key Issue in Quiet Race, N.Y. Times, Sept. 3, 1974, at 39.

Goldstein, Stevens, Cooke Backed by Beame: Mayor Endorses Candidates for Court of Appeals, N.Y. Times, Sept. 5, 1974, at 31.

Goldstein, Fuchsberg is Apparent Winner in Democratic Race for 2 Seats on Appeals Court: Cooke and Stevens Trail In a Close Fight for 2d, N.Y. Times, Sept. 11, 1974, at 32.

Goldstein, Cooke Apparent Winner of Appeals Seat, N.Y. Times, Nov. 7, 1974, at 36.

Hochberger, Appellate Division’s Presiding Justice Will Be 70 in Fall: Stevens to Retire from the Bench This Month, N.Y. Times, March 14, 1977, at 49.

In Memorandum, 76 NY2d vii (1990).

Man of Many Firsts: Harold Arnoldus Stevens, N.Y. Times, Jan. 1, 1958, at 23.

Morello, The Freedom Rider a Nation Nearly Forgot: Woman Who Defied Segregation Finally Gets Her Due, Wash. Post, July 30, 2000, at A01.

Navaez, Governor, In Court Plan, Asks to Appoint Judges, N.Y. Times, April 23, 1973, at 1.

Navarro, Judge Harold Stevens, 83, Dies, N.Y. Times, Nov. 11, 1990, at 40.

Negro Lawyer Quits Fair Practice Group: Fight for Democracy Must Begin at Home, Steven Asserts, N.Y. Times, Jan. 18, 1943, at 8.

New York State Court Unified Court System, Pioneering African-Americans in the Courts and the Legal Community Past and Present, at 17 (Feb. 1992).

New York State Supreme Court Appellate Division, First Department: 1970-Present,

www.courts.state.ny.us/courts/ad1/centennial/1970_present.shtml.

Oelsner, Appoint All the Judges? Question, Now Decades Old in State Has Philosophical and Practical Sides, N.Y. Times, Oct.6, 1972, at 86.

Oelsner, State Study Panel Said to Favor Election of Judges, N.Y. Times, Oct. 7, 1972, at 30.

Oka, Stevens Hopes to Enlarge Court Innovation Begun by Botein, N.Y. Times, Oct. 20, 1968, at 60.

Randolf: Pullman Porter Museum, Evolution of Employment on the R.R., www.aphiliprandolphmuseum.com/evo_history4.html.

Reid, Benedict Seniors Told Ability Being Recognized More Now, The Columbia Record, May 24, 1955.

Robeson, The Lowman Lynchings of 1926: A Paper for the Citadel Conference on the Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina, Dept. of History, Columbia University (March 6, 2003), available at www.citadel.edu/civilrights/papers/robeson.pdf.

South Carolina’s Information Highway, A Short History of Kiawah Island and Quash Stevens, available at www.sciway.net/hist/chicora/quash-1.html.

South Carolina’s Information Highway, Your Servant, Quash: Letters of a South Carolina Freedman, available at www.sciway.net/hist/chicora/quash-2.html

State of New York, Court of Appeals, “There Shall Be A Court of Appeals”: 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York, at 23.

Stevens, Papers: 1936-1990, available at The New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Stevens, Judge Harold A. Stevens Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals: Keep An Able and Experienced Judge on the Court of Appeals, Pamphlet (1974), available in Harold A. Stevens, Papers: 1936-1990, supra.

Wormser, Jim Crow Stories: Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/storiesorgbrother.html.

Published Writings Include:

Violence and The Law (New York State Journal of Medicine, Sept. 1, 1972, at 2157), appears to be Judge Stevens’ only published article. A complete collection of his writings and speeches can be found in Harold A. Stevens, Papers: 1936-1990, available at The New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Endnotes

- The victims were Bertha, Clarence, and Demon Lowman.

- Oka, Stevens Hopes to Enlarge Court Innovation Begun by Botein, N.Y. Times, Oct. 20, 1968, at 60.

- See Navarro, Judge Harold Stevens, 83, Dies, N.Y. Times, Nov. 11, 1958, at 40 (quoting Judge Stevens as stating, in relation to the Lowman lynchings, “[t]here was no voice of protest raised . . . [t]hen I was inspired to study law because it was our best bet to eliminate things like this”).

- Prior to 1780, Arnoldus Vandorhorst II and his wife Elizabeth Vanderhorst built a plantation house on Kiawah Island. There, they kept upwards of 30 enslaved African-Americans to tend cattle and grow subsistence crops. The British destroyed that plantation during the American Revolution. However, Vanderhorst II continued holding slaves to work the land. By 1810, the Vanderhorst family enslaved a total of 113 people and rebuilt a plantation house. Upon the death of Vanderhorst II, Kiawah passed to his son, Elias Vanderhorst, who married Ann Morris in 1821. Quash Stevens is said to have been born in either May 1840 or 1843, the apparent son of Elias. In 1864, Ann “made a deed out to her son, Arnoldus IV to ‘give and deliver unto him my slave, a Mulatto Man, named Quash.'” Quash acquired his freedom by 1865, but remained faithful to the family, who lost virtually all of their possessions on Kiawah Island after the Civil War. Census records reveal that, by 1880, Quash had four children: Eliza, William, Annie, and Laura. His wife is not listed in the census, although Quash spoke of her in his letters. In 1909, Quash and William Stevens sold the property on which Judge Stevens was born. Quash died only four months later of heart failure; he is buried at Centenary Cemetery.

- Research failed to reveal who was Quash’s mother.

- Man of Many Firsts: Harold Arnoldus Stevens, N.Y. Times, Jan. 1, 1958, at 23.

- The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was the first African-American labor union to sign a collective bargaining agreement with a major United States corporation. In 1925, A. Phillip Randolf (1889-1979) organized the independent union, which was made up of sleeping car porters and maids, who worked for the Pullman Company. The Pullman Company owned and operated the majority of sleeping passenger trains at the time. By the 1920s, 20,224 African-Americans were working as Pullman Porters and train personnel. The group made up the largest category of African-American labor in the United States and Canada (see A. Philip Randolf: Pullman Porter Museum, Evolution of Employment on the R.R., http://aphiliprandolphmuseum.com/evohistory4.html; see also Richard Wormser, Jim Crow Stories: Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/storiesorg_brother.html; Eric Arnesen, Brotherhoods of Color: Black Railroad Workers and the Struggle for Equality [Dec. 2000]).

- Ella Clyde Meyers Stevens, now deceased, was born in Columbia, South Carolina to the late Isaiah and Ola Myers. She graduated from Benedict College and later undertook graduate studies both in New York and Chicago. Ella retired as a teacher in the New York City Public School system, and has a legacy of engaging in various religious, charitable, and social activities throughout her lifetime (see Obituary Notice, N.Y. Times, Nov. 8, 2003).

- Oka, Stevens Hopes to Enlarge Court Innovation Begun by Botein, N.Y. Times, Oct. 20, 1968, at 60.

- Id.

- Negro Lawyer Quits Fair Practice Group: Fight for Democracy Must Begin at Home, Steven Asserts, N.Y. Times, Jan. 18, 1943, at 8.

- Id.

- The Reorganization Act of 1866 authorized African-American Army units identified as the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry and the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-fifth Infantry. The units acquired the moniker Buffalo Soldiers from Plains Indians, who likened their bravery to that of the buffalo and their hair to a buffalo mane. Celebrated for their valor, the Buffalo Soldiers “remained together and fought in both world wars and Korea, before being integrated into the rest of the army in 1952” (see Susan Altman, Buffalo Soldiers, Encyclopedia of African-American Heritage [2d ed.]). In 1993, the Buffalo Soldier monument was dedicated at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. At the dedication, then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Colin Powell, said: “There he is, the Buffalo Soldier on horseback . . . brave, iron-willed, every bit the soldier that his white brother was. African-Americans had answered the country’s every call from its infancy, yet the fame and fortune that were their just due never came. For their blood spent, lives lost, and battles won, they received nothing. They went back to slavery, real or economic, consigned there by hate, prejudice, bigotry, and intolerance . . . I am deeply mindful of the debt I owe to those who went before me . . . don’t forget their service and sacrifice” (see National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Presidio of San Francisco: The Final Years, www.nps.gov/prsf/history/buffalosoldiers/finalyears.htm [last updated Dec. 18, 2004], quoting Colin Powell & Joseph E. Persico, My American Journey: An Autobiography, at 556-557 [Random House, NY 1995]).

- See 38 US 373, 374 (1946).

- United Nations Charter, Article 55-c provides: “With a view to the creation of conditions of stability and well-being which are necessary for peaceful and friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, the United Nations shall promote . . . universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.” Article 56 states: “All Members pledge themselves to take joint and separate action in co-operation with the Organization for the achievement of the purposes set forth in Article 55.” The Charter was opened for signature in 1945.

- The ruling did not have immediate impact, and did not end segregation on transportation within the state. Eleven years after Irene Morgan refused to give up her seat, Rosa Parks refused the same order as a passenger on a Montgomery, Alabama city bus. Irene Morgan’s bravery has been called “the stick of dynamite in a cornerstone of institutionalized segregation” (Carol Morello, The Freedom Rider a Nation Nearly Forgot: Woman Who Defied Segregation Finally Gets Her Due, Wash. Post, July 30, 2000, at A01). Morgan “inspired the first Freedom Ride in 1947, when 16 civil rights activists rode buses and trains through the South to test the law enunciated” therein (id.).

- Oka, Stevens Hopes to Enlarge Court Innovation Begun by Botein, N.Y. Times, Oct. 20, 1968, at 60.

- Id.

- Id.

- New York State Supreme Court Appellate Division, First Department: 1970-Present, www.courts.state.ny.us/courts/ad1/centennial/1970_present.shtml.

- Goldstein, 3 Candidates for Court of Appeals Find Experience is Key Issue in Quiet Race, N.Y. Times, Sept. 3, 1974, at 39.

- In Memorandum, 76 NY2d vii (1990).

- Id.

- Stevens, Judge Harold A. Stevens Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals: Keep An Able and Experienced Judge on the Court of Appeals, Pamphlet (1974).

- Goldstein, 3 Candidates for Court of Appeals Find Experience is Key Issue in Quiet Race, N.Y. Times, Sept. 3, 1974, at 39.

- Id.

- Goldstein, Stevens, Cooke Backed by Beame: Mayor Endorses Candidates for Court of Appeals, N.Y. Times, Sept. 5, 1974, at 31.

- Asbury, Fuchsberg Wins Appeals Contest: 96% Tally Shows He Beat Stevens by 81, 133 Votes, N.Y. Times, Nov. 8, 1974, at 82.

- NY Constitution, Article VI, ‘ 2.

- Reid, Benedict Seniors Told Ability Being Recognized More Now, Columbia Record, May 24, 1955.

- Id.