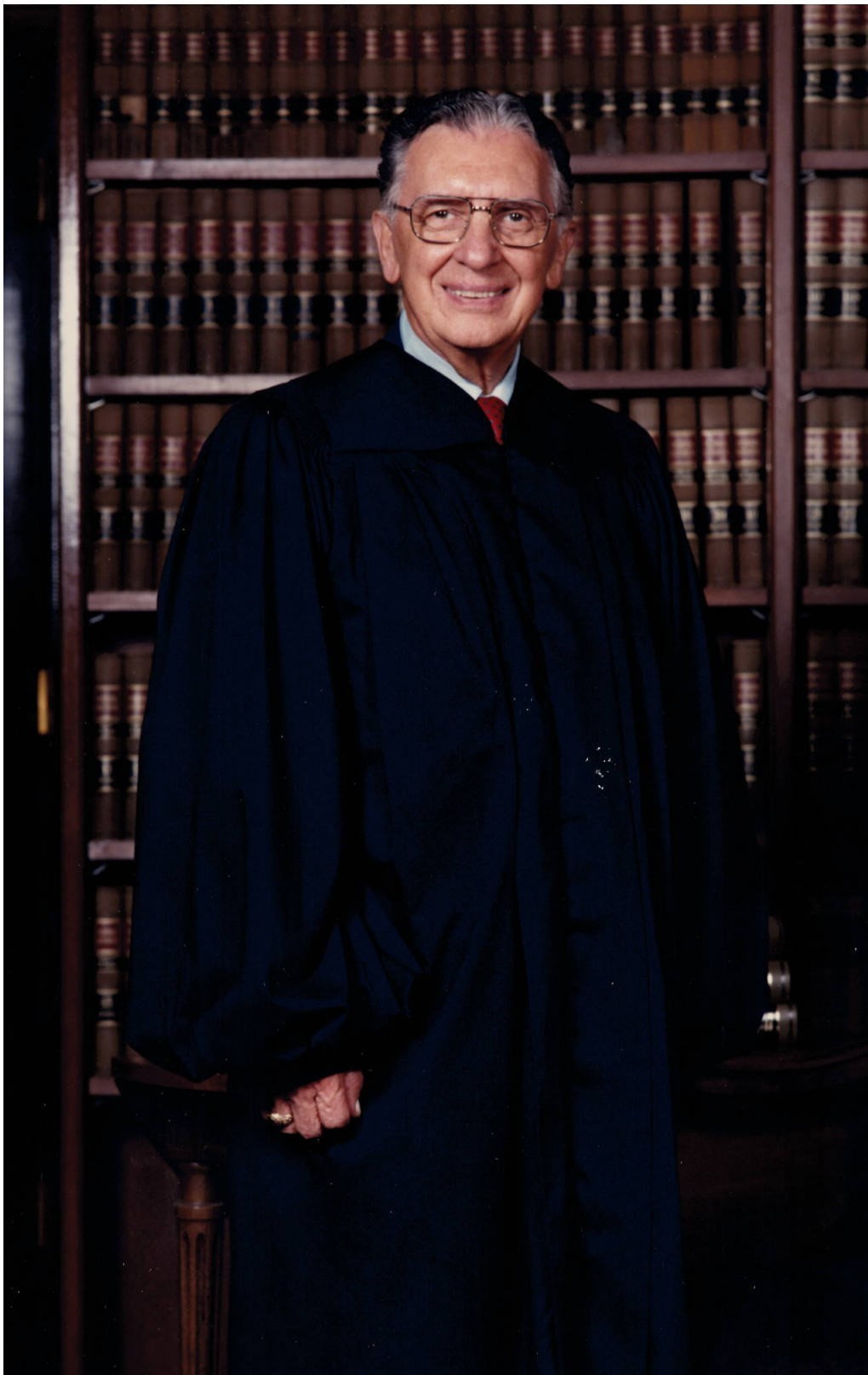

On April 28, 2016, Hon. Xavier C. Riccobono, Administrative Judge of Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County from 1983 to 1991, a judge for 35 years, and a Justice of the Supreme Court from 1968 to 1992, passed away, peacefully and surrounded by family. He had celebrated his 100th birthday on April 2, 2016 with scores of family and friends visiting him at home.

Justice Riccobono was the child of immigrants from Sicily. As a boy and young man, he helped the family to weather the Great Depression by working in the family’s fish store. He graduated from Xavier High School, New York City. The young Xavier’s experience at the school was, as he would often suggest throughout his life, of enormous importance to him. Thanks to teachers and mentors, his time at Xavier High School enabled him to set his moral compass and bring to the fore the values, standards, and principles that would guide him ever after. In addition, the school then had a mandatory military training pro- gram, and he was able to rise through the ranks of that program, benefitting greatly from the training and responsibilities associated therewith.

The future judge graduated from Fordham University in 1937 and in 1939 from Fordham Law School. He was in private practice for several years, but war clouds were of course gathering and he soon enlisted in the Navy. During World War II he served in Sheepshead Bay as a legal officer responsible for non-judicial disciplinary proceedings known as the Captain’s Mast. In addition, he was sent on a special mission in the Pacific theater. His reports from that mission helped convince the Navy that sixteen-year-old “sailors” were unfit for combat duty. He completed his service in 1946, leaving the Navy with the rank of Lieutenant Commander.

Back home, he returned to private practice. In 1949, he married the love of his life, the extraordinarily kind, gracious, and lovely Sylvia.

In 1956, he was appointed to the Municipal Court. In 1962, the Municipal Court and the City Court were merged into a new Civil Court of the City of New York. In 1968, Judge Riccobono was elected a Justice of the Supreme Court. He served on both the civil and criminal branches of the Supreme Court, and gained a reputation as an effective and fair-minded Justice. Justice Riccobono’s merits were recognized in 1983, when he was designated the Administrative Judge of Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County, in which capacity he was to serve with great distinction until 1991. He also served as a Justice of the Appellate Term, First Department.

During his long tenure as Administrative Judge, Justice Riccobono was involved in many important initiatives. Among them the most challenging was the introduction in 1986 of the Individual Assignment System (IAS), an epochal event in the history of the state’s court system. Before that time, the New York State courts had employed the so-called Master Calendar System. Under this system, cases were not assigned to specific judges for all of their life or even a good part of it. Rather, through the use of master motion calendars, motions in any given case were assigned, a motion at a time, to different judges on a rotating basis. If 10 motions were made in a case, they might be handled by 10 different Justices. When the case was ready for trial, it would appear on a Master Trial Calendar and it would only be a matter of fortuity whether the Justice to whom it was then assigned had had any involvement with that case or its motions before that point.

In contrast, the United States District Courts and some state court systems at that time employed generally an Individual Calendar System in which cases were assigned to judges from the inception of the case until conclusion.

Our court system came to recognize that the Master Calendar System was intolerably inefficient and antiquated. The knowledge about a case that a Justice – – probably several different Justices – – gained from work on motions was wasted. The fact that cases bounced around from Justice to Jus- tice when motions were made also created inevitable difficulties from the perspective of consistency in judicial rulings.

The Master Calendar System also fostered judicial distance from the discovery process. The court system was indifferent to the efficiency of the discovery process and to pre-trial proceedings in general except to the extent that motions were made directed to such matters. No judge was responsible for the truly vital matter of the progress of each case overall, for ensuring that litigants received a day in court expeditiously and at a reasonable cost. The lack of an ongoing judicial role in supervision of pre-trial proceedings in practice meant tolerance for delay and gamesmanship and abuse of the discovery process by unscrupulous attorneys. New York’s laissez-faire approach to pre-trial supervision was also out of step with that followed in the federal courts and in many state court systems.

By the late 1980’s, the drawbacks of the Master Calendar System were becoming clear. When Judge Sol Wachtler became Chief Judge of the State of New York in 1985, he directed Administrative Judges throughout the state to adopt an Individual Assignment System (“IAS”) in lieu of the Master Calendar System. New York County, under Justice Riccobono’s leadership, and with the assistance of then-Chief Clerk Jonathan Lippman (who was, of course, later to become New York’s Chief Administrative Judge and then its Chief Judge), was instrumental in piloting this transition to IAS, including drafting the revisions of the Uniform Rules of the Supreme and County Courts that were required for that to happen. The introduction of the IAS system was a critical initiative. This step almost certainly represents the most significant operational development on the civil side in our court system over the past half century or more until the advent of electronic filing.

As with any other change of importance, the introduction of IAS encountered opposition in some quarters of the Bar and the judiciary. Some attorneys, for instance, opposed the system because they feared judicial involvement in the progress of the case. “It is up to the lawyers to push their cases,” they would say, although, of course, the clients expected that the courts would ensure that they received their day in court in a reasonably prompt and efficient manner. Some judges at the time, who had been intimately familiar with the prior system since before coming on the bench, were similarly resistant. Stalwart and effective leadership was called for and that is just what Justice Riccobono pro- vided. Judge Riccobono and his administrative team had to, and did, labor with great diligence, persistence, and patience to overcome what one might call these cultural headwinds. Change is always difficult, major change more so, but in this venture he succeeded very well. By 1989, if not earlier, the new system was well-established, with only a few holdouts still resisting it. His work putting the new system into place and confronting and overcoming objections to it created the basis for the active judicial case management practice that has been in operation ever since and that we now implement as a matter of routine.

Judge Riccobono recognized something that some of the critics at the time may have missed – – the new system brought with it an enhancement of the role of the judge in the state courts. Under the Master Calendar approach, the judge was a critical, but interchangeable and, in a sense, faceless actor in the process of administering justice and was officially required to be indifferent to the very important matter of discovery and pre-trial progress. Under the new system, each justice had her or his own inventory and was in charge of every aspect of every case in that inventory all the way through.

Such individualized judicial involvement in cases is, we think, the preferred method to achieve consistent justice, efficiency in discovery, and reasonably expeditious processing of cases. New York County remains a prominent exponent of the IAS approach that Justice Riccobono first developed here. Although there have been modifications to the IAS system in the years since its introduction in some counties, even there cases do not bounce from Judge to Judge at random when motions are made and conferences are conducted in an effort to ensure that discovery disputes are avoided insofar as possible, such disputes as do arise are resolved quickly, and the costs of discovery are minimized.

The new IAS system also presented very significant operational challenges. Because these challenges were technical, their importance no doubt was underestimated by some, but not by Judge Riccobono. He recognized that the new system could founder if proper administrative procedures were not in place. Before the change there were only two centralized Parts in the court for pre-trial matters: Special Term Part I for motions and Special Term Part II for ex parte matters, and two centralized Parts for trials, Trial Term Part I for trials generally and Trial Term Part V for trials of matrimonial matters. In New York County, judicial assignments to Special Term Part I were for one week with the Justice assigned then serving a second week in Special Term Part II. In contrast, with IAS, there would be many IAS motion and trial Parts. Under the Master Calendar System, motion papers on motions on notice were delivered to a single Part. Under the new system, papers would have to be dispersed to many Parts and each Part would have its own motion calendar. The same was true of ex parte applications. Ways had to be found to keep track of all motion papers and ex parte applications in these many Parts and ensure that they were always delivered to the Part to which they belonged. Appearances by counsel prior to trial had been concentrated in these two pre-trial Parts, but under IAS they would now occur in a multitude of Parts. Processing appearances and handling adjournments would be tasks distributed among all the many new Parts. Before the change, there were no Parts ad- dressed to the supervision of discovery. After it, each IAS part had an inventory of cases that required pre-note supervision, particularly with regard to discovery. The proverbial devil was, in this instance, actually many devils and they were in these details, which, if not handled correctly, could have under- mined the admirable goals of the new system.

These technical challenges demanded that the court substantially, indeed from top to bottom, revise its operating procedures. This required a thorough examination of every aspect of operations and sweeping new thinking about how best to proceed. In response to this complete overturning of the old administrative order, Judge Riccobono, then-Chief Clerk Jonathan Lippman, and their administrative team had to develop procedures that would achieve smooth and efficient processing of all cases and all papers and assure accurate record-keeping, while at the same time being practical and administratively manageable for the staff as it was. The Judge recognized that extensive training for all court staff would be essential to the success of the effort. In addition, a great deal of outreach to the Bar was needed to assist attorneys to understand and navigate the new pathways because the new system represented a revolution for the Bar as well. The Justices of the court had to be consulted extensively as these changes were being developed and implemented and trained in the new procedures once they had been arrived at.

The responsibility for all decisions on these questions and carrying out the communications with and training of all concerned rested with Judge Riccobono and Chief Clerk Lippman. Their work with the staff, the Bar, and the Justices on operational issues was very successful. The decisions taken by them proved to be sound ones. The proof of this statement lies in the fact, probably not generally appreciated now, but true all the same, that these decisions have largely governed our operations from that point until the present, 30 years later. Modifications and improvements were made over time, of course, including by Judge Riccobono himself, but the implementation of the new procedures was smooth, no great difficulties were encountered, and the basic system has worked without any such problems ever since.

Before the IAS system was introduced, record-keeping in our court was, by today’s standards, primitive. Case history information was sparse and such records as existed were created and maintained using the technology of the 19th century, which is to say, by hand. The more complex nature of the new system required technological assistance, which arrived in 1985 in the form of the Civil Case Information System, or “CCIS” as it has mostly been called ever since. CCIS was a computerized case history system. Assignments were effectuated through it at random and the assignment of cases to an individual Justice could be recorded there. Appearances and motion filings were recorded in it. Motion and conference calendars were created by it and printed from it.

Necessary and welcome as CCIS was, it presented a major challenge initially. The application was complex and computer technology was something with which almost no one at the court was familiar at the time, an era of rotary telephones. The introduction of IAS required intensive training to familiarize all of the court’s clerks with the new system, and this technological training arrived at a time when the court and staff were already struggling with adapting to new operating procedures.

Only a limited opportunity was made available to court administrators in the districts to request changes in CCIS. Thus, in more than a few respects our court had to adapt its operating procedures to the requirements and limitations of CCIS. Judge Riccobono, Chief Clerk Lippman, and our Department Heads had to lead the staff down the new technological path when more than a few were hesitant, uncertain, or resistant to change. The Judge and his team had to instill in all of the staff and Justices confidence that the new application would work out well enough in implementing our new proedures to permit the court to perform its functions without undue difficulty. The introduction of CCIS went quite well. Within months the court was handling all of the IAS work in a timely manner and recording it accurately in CCIS. Here, too, Judge Riccobono’s positive, optimistic, caring leader- ship was determinative of the success of the application in our court.

It is remarkable that today, over 30 years later, CCIS carries on as our court’s case history application despite its advanced age (though it is soon to be replaced). In the field of technology, 30 years is many eons. The fact that we have been able to function as well as we have for so long is a testament to those in the Unified Court System’s Department of Technology who designed CCIS in the first place, maintained it, and developed and implemented the adjustments needed to keep it functioning thereafter in changed environments and an era of vastly greater caseloads. Much credit is owed to the staff of our court for making a great many fruitful suggestions about how DOT ought to improve CCIS. Not only has CCIS allowed us to keep track of our cases, but it has served as the foundation for the Case Management software program, our Supreme Court Records On-Line Library (Scroll) application, the e-Track notification application, and some measure of automated data transfer from the electronic filing program. Data feeds to the Bar, the Law Journal, and other outlets and wider public access to court records came about through CCIS. Our ability to make so much use of CCIS for such a long time is also due in part to the leadership of Judge Riccobono, Jonathan Lippman, and their administrative team, who established the procedures that have allowed staff over these decades to function successfully with the application.

During Judge Riccobono’s tenure as our Administrative Judge, under his leadership, and thanks to the decisions he made, this court successfully left behind operational practices associated with courts in the 19th century. We transformed our operations into those of a more modern, efficient court system, one committed to reducing delay and litigation expense and to better serving the interests of all parties.

Judge Riccobono had a deep commitment to the maintenance of our historic New York County Courthouse and to the preservation of its artistic elements. The courthouse opened in 1927 and was thus almost 60 years old when Judge Riccobono assumed his duties as Administrative Judge. Major improvements to the courthouse occurred or were set in motion during his tenure as Administrative Judge. He worked closely with then-New York County Clerk Norman Goodman on many of those projects, including the conservation and restoration of our great rotunda mural. Following this resto- ration, the mural was truly resplendent, and it still is (notwithstanding some damage suffered a few years ago), but, as Judge Riccobono’s example teaches us, we need to be vigilant to address the inevitable wear and tear of time. Art work throughout the first and second floors was also conserved and restored during Judge Riccobono’s tenure, and was recreated entirely in some of the first and second floor radiating corridors, where designs had been painted over.

Under the leadership of a facilities committee headed by County Clerk Norman Goodman with support from Judge Riccobono, historic chandeliers and important light fixtures were restored, air conditioning was introduced throughout the building, the portico steps were dismantled entirely and reset, and the exterior of the courthouse, which had become blackened with soot and ash, was cleaned. Long after his retirement, Judge Riccobono would express his great affection for and pride in our courthouse, which, thanks to the many movies and television series produced on location here, has be- come known to millions around this country as a symbol of our aspiration for justice.

We have only touched on some of Judge Riccobono’s accomplishments and activities as Ad- ministrative Judge. But it was not only his achievements that were remarkable and admirable. Judge Riccobono’s temperament and personality were truly extraordinary, rarely encountered in the world at large and certainly in the legal profession. Many would have said of him that he was above all else a gentleman. By this they would have meant many things. He was a gentle man – – quiet, calm, mild. He had an optimistic outlook on life and people that colored everything he did. He was unfailingly courteous and kind to everyone without exception and regardless of station, standing, titles, education or means. He did not lose his temper, with lawyers or staff; indeed, it is not clear that he had one. Even though an experienced judge and the Administrative Judge of this court, he was completely de- void of ego or arrogance. Whether he was speaking with the Chief Judge of the state or the newest and most inexperienced of court staff, he spoke in the exact same way. He cared about the well-being of his Justices and all his staff. These wonderful personal qualities marked Judge Riccobono as a per- son of exceptional moral stature. Indeed, he exuded a spiritual quality, which no doubt was a reflection of his own innate goodness and his deep religious faith. “St. Ricky” became widely employed as a sincere term of endearment for Judge Riccobono, who, however, being the kind of person he was, would have been seriously embarrassed by it.

He was such a lovely man to all, so even-tempered and calm, that some grizzled administrative types sometimes wondered how he was able to accomplish so much as Administrative Judge. He was not “tough” in the conventional sense. But those who had brought about his designation as Administrative Judge well knew what they were doing. He functioned as a judge so well because he treated all attorneys, litigants, and witnesses with sincere respect, which inspired respect in those with whom he came into contact. He acted no differently with his colleagues and the staff of the court in his dealings as Administrative Judge. Always he offered a positive vision and he sought to promote collabo- ration and to empower Justices and staff in pursuit of this common purpose. He listened to everyone and took the views of all into account. He responded when someone had a good idea, whoever she or he might be. He was so friendly and kind in these dealings and displayed so light a hand that it was hard for those hearing him to resist his entreaties; no one wanted to disappoint Judge Riccobono.

The Judge was the recipient of many important professional honors, including the Charles A. Rapallo Award from the Columbian Lawyers Association (1977), the Harlan Fiske Stone Award from the Trial Lawyers Association of the City of New York (1982), and the Louis J. Capozzoli Gavel Award from the New York County Lawyers’ Association (1986).

In 1992, Judge Riccobono retired at age 76 and with his beloved Sylvia relocated to Toms River, New Jersey. He never forgot about this court, however, his court. Frequently, he would telephone old friends here and inquire about how things were going in the court and how friends were doing, and sometimes he would come for a visit. He would invariably call to offer good wishes for Thanks- giving, Christmas, the New Year, and the Jewish High Holy Days. He remained deeply interested in this court and its people. Indeed, some of us were speaking with him only days before his passing. He was blessed with extraordinary good health and his faculties remained as acute as they had been decades before. Across the phone line would come Judge Riccobono’s voice, distinctive and lilting, so familiar to many of us who had had the great privilege of working for him, although he undoubtedly would dispute that characterization by saying that we worked “with him.”

It was a source of great satisfaction to Judge Riccobono when, in 2015, he attended the admission to the New York Bar at the Appellate Division, First Department of his grandson, Justin R. Mahony, himself a graduate of Fordham Law School. Some of us joined the family at the Appellate Division for the occasion and photographs showed Judge Riccobono all smiles (as he so often was) at this happy event. Justin carries on his grandfather’s great tradition of public service as an Assistant Law Clerk in our court.

It was a source of great satisfaction to Judge Riccobono when, in 2015, he attended the admission to the New York Bar at the Appellate Division, First Department of his grandson, Justin R. Mahony, himself a graduate of Fordham Law School. Some of us joined the family at the Appellate Division for the occasion and photographs showed Judge Riccobono all smiles (as he so often was) at this happy event. Justin carries on his grandfather’s great tradition of public service as an Assistant Law Clerk in our court.

As we say, in early April of this year, Judge Riccobono celebrated his 100th birthday. Even today, when medical miracles are taken for granted, it is rare for someone to reach that milestone.

But of him it can truly be said that he led a life that was as productive, useful, happy, and honorable as it was long. Judge Riccobono’s legacy in our court remains vibrant to this day and permeates so much of what we do. Indeed, few have had a larger impact than Judge Riccobono had for the good of this court, its justices and staff, and the citizens it serves.

The Judge is survived by two children and their spouses, Lorraine (Bob) and Anthony (Phyllis), and two grandchildren, Steven and Kristen, in addition to Justin. He is also survived by his court family. Since the Judge lived such a long life, there are many here now who came to the court after the Judge had retired. But he would consider them too part of the family. In accomplishing all that they have over the years since, they have built upon the very solid foundation laid back then by this wonderful man.