Theodore Theopolis Jones, Jr. was the fourth African American appointed to serve on New York State’s highest court. He was nominated to the Court of Appeals by the then-newly elected Governor Eliot Spitzer in January 2007 and confirmed by the State Senate in February 2007. Sadly, Judge Jones’s time on the Court was cut short when he passed away unexpectedly on November 6, 2012 at the age of 68.

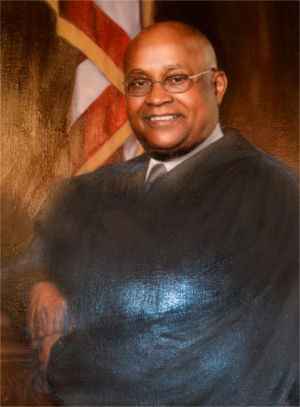

On February 15, 2013, Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman, speaking at the Court of Appeals’ annual Diversity Day event to celebrate Judge Jones’s life and unveil his portrait at Court of Appeals Hall, said of his colleague and friend, “Ted Jones was not like anyone else I’ve ever known, and was not like anyone else in the history of the Court of Appeals. He had a singular personality that absolutely captivated us—he was smart, charming, gentle, street-wise, down to earth, and down-right inspiring.”1 Recounting how Judge Jones’s colleagues on the Court viewed him, Chief Judge Lippman further said, “Ted’s warm demeanor, and his insightful grasp of the intricacies of the legal cases confronting the Court, made him an instant favorite of his colleagues. When Ted Jones spoke at conference or asked questions from the Bench, we all listened knowing that he was always wise, cogent and insightful in expressing his views on the law.”2

Dean Michael A. Simons of St. John’s University School of Law, where Judge Jones taught for several years, further wrote, “New York State lost a public servant of intense intellect, impeccable integrity, and deep compassion. St. John’s lost a dear friend.”3 In describing Judge Jones, Dean Simons focused on three words: “humility, compassion, and service.”4 He wrote:

When you met Ted Jones, you wouldn’t have known that he was a great lawyer or a great judge, and that’s because he carried himself with such genuine humility-a humility that I believe grew out of his understanding of other people. It is impossible to be a criminal defense lawyer and not have a deep understanding of and compassion for the struggles that affect others’ lives. And Ted Jones’ compassion for others led him to a lifetime of service.5

The foregoing remarks and the many other tributes celebrating Judge Jones’s life provide a glimpse of the type of man Judge Jones was and the high esteem in which he was held. However, to uncover the full measure of the man and understand what informed his views and shaped his values, we necessarily start at the beginning.

Family History, Early Years and Education

Judge Jones was born in Brooklyn, New York on March 10, 1944, to Theodore T. Jones, Sr. and Hortense Parker Jones of Newport News, Virginia. The youngest of three children, Judge Jones was affectionately known as “Teddy” to his family and friends. His mother, one of 13 children, was an educator, while his father worked for the Long Island Railroad, eventually becoming the Stationmaster at Pennsylvania Station.6

“Teddy” and his siblings were greatly influenced by their parents and their extended family of aunts and uncles. These close-knit family members stressed the importance of hard work and, through their own professional achievements in business, law and education, demonstrated many other valuable qualities. In fact, Judge Jones’s decision to pursue a career in law was influenced by his uncle Lutrelle F. Parker, Sr., a patent attorney who was the first African American to hold the positions of Deputy and Acting Commissioner at the United States Patent and Trademark Office. The Jones children were always encouraged to strive for excellence and to take advantage of educational opportunities; Judge Jones’s sister, Theodora J. Blackmon, has a Master’s Degree in Education, and his brother, Lawrence Jones, has a Doctorate in Education.

Judge Jones’s parents owned a 120-acre farm in Delaware County, New York, where they ran a summer camp and brought children from Harlem to spend time in the country. This farm played an important part in Judge Jones’s development and family life. Well known to his colleagues and friends as an avid golfer, Judge Jones was also a sportsman. It was at the farm where Judge Jones learned, from his father, how to fish, hunt, and ride a horse. In later years, the farm became a place where family and friends would gather to spend time together.

Back home, Judge Jones was a product of New York City public schools. He originally attended P.S. 93 elementary school in Brooklyn. When the family moved to Jamaica, Queens in 1952, he transferred to P.S. 123 and Shimer Junior High School. Significantly, it was at Shimer where Judge Jones met Joan Sarah Hogans, who would become his wife.

After graduating from John Adams High School in Queens, Judge Jones attended Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Hampton, Virginia, along with his siblings. While at Hampton, he was involved in a number of student organizations. He also joined the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Gamma Epsilon Chapter, in the spring of 1963 and the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). He graduated in 1965 with a Bachelor of Science Degree in History and Political Science. At his graduation, he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the United States Army.

Judge Jones served as a Field Artillery Officer and subsequently completed Special Forces training at the John F. Kennedy School of Special Warfare at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He was then stationed in the Republic of Vietnam where he served his country with distinction and honor from June 1968 until July 1969. He relinquished his commission at the rank of Captain.

Making His Mark as an Attorney

Upon his return home, Judge Jones decided to pursue a legal career. He graduated from St. John’s University School of Law in 1972 with a Juris Doctor degree and was soon after admitted to the New York State Bar.

Judge Jones began his legal career working for the Community Defender Office of the Legal Aid Society, Criminal Defense Division, located in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, New York. This was a small neighborhood office where the staff attorneys represented clients from arraignment through the disposition of their cases. This office was funded by a federal program called Model Cities, which was founded in 1966 by President Lyndon B. Johnson and supported novel and alternative means of municipal government. After leaving the Community Defender Office, Judge Jones served as Law Secretary to the Hon. Howard A. Jones (no relation) of the New York State Court of Claims.

In 1975, Judge Jones established a private practice on Fulton Street in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, New York, later moving to downtown Brooklyn at 16 Court Street. Although Judge Jones was a general practitioner, he relished the challenges associated with the practice of criminal law and quickly developed into a skilled trial attorney, taking on pro bono cases when individuals accused of crime lacked financial resources.

In the first felony case Judge Jones tried, he represented a young teenage boy who was charged with robbery. Working with investigators, he found two witnesses who remembered seeing, at the time of the crime, the defendant bouncing a basketball in a park far away from the scene. The two witnesses, both elderly women, had reservations about getting involved. Judge Jones persuaded them to come forward and testify in court on behalf of his client. The young man was acquitted.

Judge Jones’s ability to read people and situations enhanced his skill as a criminal defense attorney. On one occasion, while representing a client in a murder case involving grisly facts, he decided to waive a trial by jury and try the case in front of a judge with a reputation for being extremely tough. This was thought to be a very risky decision. In making this call, Judge Jones thought that, due to the facts of the crime, his client would be found guilty by a jury regardless of his defense. He also believed that the assigned trial judge would consider only the evidence and make a decision devoid of passion. Judge Jones was right; his client was acquitted.

Transition to the Bench

In 1989, after a long and successful career in private practice, Judge Jones was elected to serve as a Justice of the New York State Supreme Court for a 14 year term and was later reelected in 2003. The move from highly respected trial attorney to trial judge was a logical next step for Judge Jones. He wanted to effect wide-reaching change in the legal community and in the lives of ordinary litigants. Further, he understood the challenges facing litigants and their attorneys.

Starting in September 1993, Judge Jones presided over the Juvenile Offender Part in Kings County, handling cases involving juveniles charged with felonies under the Juvenile Offender Law. This specialized Part was modeled after the Youth Part in the Supreme Court of New York County and was designed to focus attention and scarce resources on youth who were being prosecuted as adults. The aim was to reduce the delays in youth cases, provide consistent sentencing, increase the number of youth diverted away from incarceration, and reduce recidivism by marshaling treatment resources, social services, and alternatives to incarceration. Judge Jones was by temperament and interest ideally suited to preside over this Part, and he sought to be a positive influence on the lives of the young people who appeared before him.

It was not unusual for Judge Jones, while presiding over the Juvenile Offender Part, to invite students to observe court proceedings and then talk with them about what happened. During one occasion, a group of sixth grade students from a local elementary school in Brooklyn visited Judge Jones’s courtroom where he was presiding over the preliminary hearing of a juvenile. After the hearing, Judge Jones asked the students, “Did you learn something from all that?” Several students responded, “Yes, crime doesn’t pay.” Judge Jones then took the time to explain that the cases before him involved young people almost as young as the visitors themselves. Judge Jones said, as parting words, “I hope the next time you kids come here, you’re all attorneys.”

From January 1998 through January 2006, Judge Jones presided over civil cases in Supreme Court, Kings County. Later in 2006, he was appointed Administrative Judge of the Civil Term of Supreme Court, Kings County. He served in this capacity until he was appointed to the New York State Court of Appeals to fill the seat vacated by the Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt who retired from the bench in December 2006.

2005 Transit Strike Case

In late 2005, Local 100 of Transport Workers Union of America, AFL-CIO (Local 100)—the collective bargaining representative for most employees involved in the operation and maintenance of New York City’s transit system—and the public authorities responsible for the operation and maintenance of New York City’s transit facilities (Authorities) were negotiating a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) to replace the existing CBA due to expire on December 16, 2005 at 12:01 a.m. Officers and members of Local 100 expressed a readiness to strike if a new CBA was not in place by December 16.

The Authorities brought suit against Local 100 and other transportation workers’ unions (Local 726 and Local 1056 of the Amalgamated Transit Union) days before the expiration date and sought preliminary injunctions under the Taylor Law–specifically, Civil Service Law §§ 210 and 211.7 After considering the parties’ evidence and hearing oral arguments, Judge Jones is-sued preliminary injunctions enjoining members of the transportation workers’ unions from, among other things, conducting, engaging, or participating in a strike.

On December 20, 2005, after the CBA negotiations broke down, Local 100 called for an illegal strike to begin at 3:00 a.m. that morning.8 Members of Local 726 and Local 1056 also joined the strike and New York City’s mass transit system was effectively shut down. Following a hearing later that day, Judge Jones, consistent with the Taylor Law’s mandates and concerned about the crippling effects a strike would have on New York City and its residents, adjudged Local 100 in contempt of two preliminary injunctions ordering it not to strike, and imposed a $1,000,000 per day fine against the union. On December 22, 2005, at about 2:35 p.m., a tentative agreement between the Authorities and Local 100 was reached and the strike ended. It is widely believed that Judge Jones’s swift and decisive action influenced Local 100 to end the strike when it did (after roughly three days). In April 2006, Judge Jones ruled on the penalties for Local 100’s violation of the court’s preliminary injunction orders. He held the union in contempt, fined the union $2,500,000, sentenced the union president to 10 days in jail for contempt of court, and suspended the union’s right to deduct dues from the paychecks of its members.9

Judge Jones’s decisive handling of the litigation related to the 2005 transit strike, which was extensively covered by the media, brought him to public attention.10

Court of Appeals Years: 2007-2012

For almost six years, Judge Jones ably contributed to the Court’s traditions of excellence through, among other things, his written opinions and insights and suggestions during case conferences. A staunch advocate for the fair administration of justice, Judge Jones also used his time on the Court to promote change within the legal profession and the court system. As will be discussed below, he fought for increased diversity in the courts as chair of the Court’s Diversity Committee, and worked to reduce wrongful convictions and eliminate their systemic causes as co-chair of the New York State Justice Task Force.

Writing Style / A Sample of Judge Jones’s Writings

Judge Jones was most concerned about how his rulings would be “felt on the ground.” In other words, he considered the practical consequences of his rulings on those who would have to abide by them, such as current and future litigants, attorneys, and trial and intermediate appellate judges. As a result, he wrote in a dispassionate and straightforward style.

Judge Jones often told his staff that the best way to find out where a judge stands is to read his or her dissenting opinions. For his part, Judge Jones made judicious use of such opinions. He only dissented in writing when he strongly disagreed with the majority’s holding. He did not believe that dissents should be written for entertainment value or for the sake of making arguments that had nothing to do with appeal before the Court.

Turning to examples of Judge Jones’s writings, the focus first falls on his criminal jurisprudence and its impact on the Court. Several articles were written on these subjects. In 2008, for example, Professor Vincent M. Bonventre of the Albany Law School wrote about Judge Jones’s influence on the Court’s decisions in criminal cases. Professor Bonventre concluded that “the [C]ourt adopted a pro-defendant position in 32% of the divided criminal cases in the five-year pre-Jones period. It did so in 39% of those cases in the immediate two year pre-Jones period. Those figures contrast markedly with the 63% [pro-defendant decisional record of the Court] since Jones’s appointment.”11 In 2010, an Albany Law Review article analyzed eleven opinions written by Judge Jones, broken down into majority opinions in criminal cases where there was a dissenting opinion by another member of the Court and criminal cases where Judge Jones was the dissenting judge.12 The author concluded that Judge Jones’s opinions tend to favor the rights of defendants, and that his opinions have and will continue to have a distinct impact on the Court’s criminal jurisprudence.

In his criminal jurisprudence, Judge Jones, wrote on certain practices and court rulings that could potentially contribute to wrongful convictions. The criminal case summaries which follow illustrate ‘his concern in this area.

Judge Jones’s first writing on the Court was the seminal decision People v. LeGrand.13 LeGrand involved a murder where one witness to the crime, who saw the assailant up close, identified the defendant as the killer in a photographic array and lineup conducted seven years after the crime. Two other witnesses, who identified the defendant at trial after they failed to identify him in a photographic array, had seen his photograph in the same array the night before they testified. In addition, there was no physical evidence connecting him to the killing. At trial, the defendant, by motion, sought to introduce expert testimony on research concerning the following factors that may influence the perception and memory of eyewitnesses and the reliability of their identifications: the effect of weapon focus, the lack of correlation between witness confidence and accuracy of identification, the effect of post event information on accuracy, and confidence malleability. After a Frye14 hearing to determine the admissibility of the expert’s testimony, the trial court denied the defendant’s motion concluding that although the expert witness was qualified, and the expert’s proposed testimony was relevant and beyond the ken of the typical juror, the proposed testimony was not generally accepted in the relevant scientific community.

The unanimous Court first concluded that all of the proposed expert testimony, except for that pertaining to the impact of weapon focus, was generally accepted within the relevant scientific community. Further, and taking into account that trial courts generally have the power to limit the amount and scope of the evidence presented, the Court held that where the case turns on the accuracy of eyewitness identifications and there is little or no corroborating evidence connecting the defendant to the crime, it is an abuse of discretion for a trial court exclude expert testimony on the reliability of eyewitness identifications if that testimony is (1) relevant to the witness’s identification of the defendant, (2) based on principles that are generally accepted within the relevant scientific community, (3) proffered by a qualified expert, and (4) on a topic beyond the ken of the average juror.15

Another notable decision written by Judge Jones is People v. Bryant.16 In reversing the Appellate Division order affirming the defendant’s conviction, the Court held, among other things, that the defendant’s motion for a Mapp/Dunaway hearing to suppress all evidence proffered against him should have been granted.17 The unanimous Court concluded it was error to deny the defendant’s motion for a hearing to suppress evidence where he was not provided the critical information needed to support the motion — i.e., the factual predicate of his arrest — that only the People could provide. Because the defendant did not have this information, he could not allege facts disputing the basis of his arrest. In so holding, the Court reemphasized the pragmatic approach courts must take in deciding whether to hold hearings on suppression motions.18

In People v. Bailey,19 the issue before the Court was whether the defendant’s conviction for criminal possession of a forged instrument in the first degree was supported by legally sufficient evidence. Judge Jones wrote for the 5-2 majority, which held that the defendant’s mere knowledge that he possessed a forged instrument (such as counterfeit $10 bills), where the circumstances surrounding his arrest only suggest that the defendant evinced an intent to steal from the patrons of the certain restaurants he went into and out of, did not provide legally sufficient evidence from which the jury could infer an intent to defraud, deceive or injure another by way of the bills, an element required for first-degree criminal possession of a forged instrument. In so holding, Judge Jones emphasized that knowledge and intent were two distinct elements of the offense, and that a ruling that the evidence was legally sufficient “effectively stripped the element of intent from the statute and criminalized knowing possession.”20 Judge Jones further noted that intent cannot be presumed from mere knowing possession unless a statute establishes such a presumption.21

But Judge Jones did not need to be in the majority to make his mark on criminal jurisprudence. In People v. Bedessie,22 a case of first impression on the issue of admissibility of expert testimony on the reliability of confessions, the defendant recanted her confession and at trial proffered the testimony of an expert on false confessions. The trial court denied the defendant’s application for a Frye hearing and did not allow the expert’s testimony. Although the majority of the Court concluded that expert testimony concerning false confessions should be allowed if relevant to the facts of the case, they held, under the facts of this case, that the proffered expert testimony was inadmissible. In dissent, Judge Jones, joined by Chief Judge Lippman, concluded that it was an abuse of discretion for the trial court to deny the Frye hearing and exclude the expert’s testimony on false confessions (if the testimony is supported by the relevant scientific community).23 Judge Jones argued that LeGrand’s holding on eyewitness expert testimony should be extended to the phenomenon of false confessions especially where, as here, there is little to no corroborating evidence connecting the defendant to the charged crime.24

In addition, Judge Jones effectively dealt with many other criminal law and evidentiary questions. For example, his majority opinion in People v. Rawlins25 addressed the following issue of first impression: “whether DNA and latent fingerprint comparison reports prepared by nontestifying experts are ‘testimonial’ statements within the meaning of Crawford v. Washington (541 US 36 [2004]),” where the United States Supreme Court held that a testimonial out-of-court statement by a witness is inadmissible under the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment, regardless of whether the court deems the statement reliable, unless the witness testifies or the witness is unavailable and the defendant had a prior opportunity to cross-examine the witness. The People argued for an absolute rule that all business records are, by their nature, not testimonial. After analyzing the relevant constitutional requirements and case law, the Court rejected the above-mentioned absolute rule and set forth a case-by-case approach for courts to use in deciding whether DNA and latent fingerprint comparison reports, and other reports of scientific procedures, are testimonial. Under this approach, a court must consider “multiple factors, not all of equal import in every case,” that include, but are not limited to, the extent to which the entity conducting the procedure is an “arm” of (influenced by) law enforcement; whether the contents of the report are a contemporaneous record of objective facts, or reflect the exercise of “fallible human judgment”; and whether the report’s contents directly link the defendant to the crime or amount to the type of ex parte communication the Confrontation Clause was designed to protect against.26

Judge Jones also wrote on important civil law issues. For example, Williamson v. Pricewaterhouse Coopers LLP27 presented the Court with its first opportunity to address whether the continuous representation doctrine, which tolls the statute of limitations for filing malpractice lawsuits against certain professionals until the professional’s representation concerning the particular matter in question is completed, applied to an auditing malpractice claim. The Court held the doctrine inapplicable where the professional engagement between the parties consisted of “separate and discrete” annual engagements and such engagements did not concern “a course of representation as to the particular problems (conditions) that gave rise to the plaintiff’s malpractice claims.”28

Hotel 71 Mezz Lender LLC v. Falor29 involved the issuance of a prejudgment order of attachment on the defendant judgment debtor, a nondomiciliary garnishee of the defendants’ intangible personal property (their ownership interests in a number of business entities formed outside of New York State) who voluntarily submitted to personal jurisdiction in New York. The main issue before the Court was whether the intangible personal property the plaintiff sought to attach (i.e., the above-mentioned ownership interests) was “property” subject to prejudgment attachment under CPLR article 62. The Court answered in the affirmative, concluding that, even though the interests were not evidenced by a certificate or other written instrument, the issuance of an order of attachment in New York on the out-of-state garnishee of the defendants’ ownership interests, who voluntarily submitted to personal jurisdiction in New York State, was appropriate.30

Judge Jones’s first dissent was in Haywood v. Drown.31 As framed by Judge Jones, the question presented was “whether Correction Law § 24 violates the Supremacy Clause insofar as it bars litigants from bringing 42 USC § 1983 claims for money damages in state court against DOCS [Department of Correctional Services] employees for actions committed within the scope of their employment.” The four-judge majority held that the Supremacy Clause was not violated because Section 24 did not treat Section 1983 claims differently than it treated state law causes of action. In the dissenting opinion,32 Judge Jones, joined by Judges Robert Smith and Eugene Pigott, noted that Section 198333 specifically enables an individual, deprived of his federal civil rights by a person acting under color of state law, to bring a civil suit against the state actor, in their personal capacity, for compensatory relief. Judge Jones concluded that in Correction Law § 24, the State Legislature enacted a statute that immunized official conduct that was actionable under federal law and was inconsistent with Section 1983 and in violation of the Supremacy Clause. After granting certiorari, the U.S. Supreme Court, agreeing with Judge Jones’s conclusion, reversed Haywood v. Drown.34

Judge Jones’s Work to Increase Diversity in the Courts

One of the most important roles Judge Jones assumed during his time at the Court was that of chair of the Court’s Diversity Committee. He believed that people coming to the courts could not have trust and confidence in the judicial system if the courts’ workforce did not reflect the ethnic and racial diversity of the general public. This belief was the cornerstone of Judge Jones’s work on the Diversity Committee and the major reason why he pushed so hard to increase the minority presence in non-attorney positions in the Unified Court System and in upstate jury pools.

To that end, Judge Jones worked tirelessly to raise the public’s awareness of the need for and importance of increased diversity. In the months leading up to the last civil service exam for Court Officer, he spoke with local community leaders and certain minority bar association representatives to get the word out and encourage as many minority applicants as possible to sit for the exam. He also traveled extensively throughout the state (both upstate and downstate) and hosted events where he spoke to high school students and community groups on issues related to increasing diversity, encouraging minority students to consider the court system when choosing their careers.

In addition, Judge Jones developed and hosted the Court’s annual Diversity events which celebrated the contributions of certain prominent jurists (such as Hon. Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick [ret.], Hon. George Bundy Smith [ret.] and Court of Appeals Judges of Italian American descent, including Hon. Joseph W. Bellacosa [ret.] and Hon. Victoria A. Graffeo) and various ethnic groups.

Judge Jones’s Role on the Justice Task Force35

On May 1, 2009, Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman, in one of his first major initiatives as Chief Judge of New York State, created the New York State Justice Task Force, one of the first permanent task forces in the country to address wrongful convictions. The goals of the Justice Task Force are to (1) examine wrongful conviction cases and the issues, practices, procedures and rules contributing to wrongful convictions, and (2) recommend legislation and policy changes to reduce wrongful convictions and eliminate their systemic causes. The Justice Task Force was also created to collect, on a continuing basis, data on wrongful convictions, and monitor the effectiveness of any implemented policy changes. The creation of this task force, which includes judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, legislative representatives, legal scholars, forensic scientists and police chiefs, was an acknowledgment by the judiciary that many innocent people are wrongfully convicted.

The Chief Judge appointed Judge Jones and Janet DiFiore, District Attorney of Westchester County, to serve as co-chairs of the Justice Task Force. By the time of this appointment, Judge Jones, through his writings, had already proven himself a leading voice in the fight to prevent wrongful convictions. In addition, Judge Jones was well known as a practical man who had the ability to develop reasonable solutions under difficult circumstances. Regarding Judge Jones’s ability to steer the work of the task force, whose members had strong and in some cases widely divergent views, District Attorney DiFiore once said that he could “find ways to round the edges and bring people to consensus.”36

Under the leadership of Judge Jones and District Attorney DiFiore, the Justice Task Force made several important recommendations consistent with eliminating the systemic causes of wrongful convictions. For example, in an effort to address the problems of false and coerced confessions, the task force proposed legislation requiring the electronic recording of custodial interrogations. The recording requirement would apply only to interrogations of suspects concerning the investigation of certain serious crimes, including homicide and sex offenses.

The task force also recommended that state law enforcement offices adopt certain best practices for the administration of identification procedures in order to increase the accuracy and reliability of witness identifications. The proposed best practices cover instructions to the witness, witness confidence statements, documentation of identification procedures, photo arrays, and live lineups.

Another important measure proposed by the task force concerned expanding defendants’ post-guilty plea access to DNA testing. In particular, the task force proposed the creation of a new provision in New York’s post-conviction DNA testing statute that would allow defendants who pleaded guilty to seek post-conviction DNA testing in limited circumstances. In making this recommendation, the task force recognized how important it was to provide a formal mechanism to exonerate the innocent after a guilty plea and at the same time preserve the integrity of the plea process.

Judge Jones knew from his years as an attorney and judge how wrongful convictions taint and negatively affect the fundamental soundness of the criminal justice system, as well as the public’s view of that system. He once said in an interview, “There is absolutely no disagreement on the fact that one of the most horrendous results we can conjure up is to wrongfully convict a defendant,” but “[e]qually troubling is the fact that when that happens, the true perpetrator is still out there. . . . If the public loses faith in the integrity of criminal convictions, then we have lost control of our entire system.”37 In his role as co-chair of the Justice Task Force, Judge Jones took full advantage of the opportunity to help shape state criminal justice policy in terms of reducing wrongful convictions and eliminating their systemic causes, and raise the public’s confidence in the integrity of criminal convictions and the criminal justice system as a whole.

Significant Activities off the Bench

Judge Jones’s duties were not confined to work on the bench or in preparation of cases. In addition to serving as chair of the Court of Appeals’ Diversity Committee and co-chair of the Justice Task Force (discussed above), he served on the Committee on Character and Fitness for the Second Judicial Department, the Special Commission on the Future of the New York State Courts (the Dunne Commission), the Board of Directors of the Judicial Friends, the Board of Trustees of St. John’s University, and the Board of Directors of St. John’s University School of Law. For a number of years while he was on the trial bench, Judge Jones also contributed to the legal education of undergraduate and law students by teaching at the City College of New York and St. John’s University School of Law.

On more than one occasion, Judge Jones noted that he stood of the shoulders of those who preceded him at the Court of Appeals, including Judge Harold A. Stevens, Judge Fritz W. Alexander, II and Judge George Bundy Smith. He was always mindful and appreciative of the people, attorneys and judges who helped or were examples to him. Taking his cue from them, he took time to mentor students, attorneys, and judges who sought his advice and counsel on wide range of topics, including pursuing career-related matters, dealing with substantive legal issues, and addressing the practical realities of the legal profession. While Judge Jones’s door and phone lines were always open to anyone seeking advice, he took a particular interest in mentoring and otherwise helping minority law students and attorneys because of his feeling that there were not as many mentors or opportunities available to them.

Judge Jones was an active member of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Lawyers Association and the Metropolitan Black Bar Association.38 In addition, he supported many of the bar associations in New York State and was often an honored guest at bar association, community and court events. Judge Jones was also a frequent speaker at numerous events throughout New York State, giving commencement addresses at Pace Law School and St. John’s University School of Law. Even though he had an extremely busy schedule, Judge Jones rarely refused a request to speak at an event or otherwise lend assistance; for example he lectured at bar association and court events and served as a judge for moot court competitions.

Awards

Judge Jones received many honors, acknowledgments, and awards during his career, including: The Brooklyn Bar Association’s Judicial Excellence Award and Special Appreciation Award; The Catholic Lawyers Guild Award; The Jewish Lawyers Guild Award; The Judicial Friends’ Lifetime Achievement Award; The Legal Aid Society’s Distinguished Alumni Award; The Macon B. Allen Black Bar Association’s Thurgood Marshall Lifetime Achievement Award; Medgar Evers College President’s Medal; The National Bar Association’s Gertrude Rush Award; The New York City Trial Lawyers Association’s Excellence in Jurisprudence Award; The New York State Bar Association’s Diversity Trailblazer Award and Lifetime Achievement Award; The New York State Court of Claims’ Judicial Achievement Award; The New York State Trial Lawyers Association’s 2007 Annual Law Day Award; The Rochester Black Bar Association’s Champion of Diversity Award; The Rockland County Bar Association’s Judicial Achievement Award; The St. John’s University School of Law’s Alumni Achievement Award and Distinguished Alumni Award; The Westchester County Black Bar Association’s Constance Baker Motley Judiciary Award; . The foregoing list is not exhaustive. Judge Jones was also named an honorary member of the Kings County Inns of Court and honored by other organizations, including the Metropolitan Black Bar Association, the Tribune Society, and the Brooklyn Women’s Bar Association. In addition, Pace Law School and St. John’s University School of Law each awarded Judge Jones an Honorary Doctor of Laws Degree (LL.D.).

Family

Judge Jones and his wife Joan were married for 45 years. They have three sons, Theodore III, Wesley, and Michael (deceased). Theodore III and his wife Theresa have two children, Kira and Theodore IV, and live in Connecticut. Wesley and his wife Yendelela live in New York. Both Theodore III and Wesley graduated from Hampton University, their father’s alma mater. Theodore III graduated from Fordham University School of Law and is engaged in the private practice of law in Connecticut. Wesley has a Master’s Degree in Computer Science from Marist College and works as a Software Engineer for IBM in New York.

Personal Reflections from Judge Jones’s Staff

Judge Jones shared a unique relationship with his staff and created a supportive, collaborative, almost familial environment in chambers. The following remarks are by some of the people who worked side by side with him: Judge Jones’s long-time confidential secretary Dora Hancock and his former Court of Appeals law clerks, Janice E. Taylor, Clifton R. Branch, Jr., Juan C. Gonzalez, Douglas Tang, Sandra H. Buchanan, and Jay Kim.

Janice E. Taylor, a friend of Judge Jones and godmother to his oldest son, wrote a little about her friendship and work with Judge Jones:

In 1972, I was a Legal Aid Society attorney assigned to Part AP3 of Criminal Court in Manhattan when one of my colleagues introduced me to Judge Jones (“Ted”) who had been her law school classmate. Within the year, both Ted and I were attorneys in a community based Legal Aid Society criminal defense program in Brooklyn. Although he was very serious about work and determined to be an outstanding trial attorney, he was also light-hearted and witty. Soon thereafter, Ted introduced me to his wife Joan and I became a regular visitor at their home. Ted, a big football fan, insisted that if I were to be a guest in their house on Sunday afternoons, I had to be able to follow the game of football. I had no interest in sports, least of all football. However, as anyone who knew Ted Jones could attest he worked his will over you. I had to learn about the game of football. That was the beginning of a friendship which embraced our extended family and friends.

In 2002, thirty years later, I was working as Judge Jones’ law clerk. This position gave me the opportunity to see an outstanding jurist at work. He had all of the qualities that lawyers and litigants appreciate in a trial judge. He had an excellent grasp of the legal issues and was fair to both sides, treating the lawyers appearing before him with respect. If he was confronted with a novel issue, he would “hit the books” and dive into Westlaw. No matter how difficult or complicated the case, or how pressured the schedule, he was always calm. This was very evident in his handling of the Transit Strike case.

The appointment of the Judge to the Court of Appeals came as a shock, at least to me. We knew nothing about the inner workings of the Court. In fact, neither Dora, the Judge’s secretary, nor I, even after the Judges’ selection imagined that we would be traveling to Albany. When those first boxes filled with briefs and records on appeal arrived in our Supreme Court Chambers, I was overwhelmed. Needless to say, Judge Jones was calm. He embraced the new responsibility and assured us that it would be an adventure. And that it was. As was discussed earlier in this biography, the first case Judge Jones was assigned was a criminal case involving eyewitness identification. I think that was a propitious start of the Judge’s career at the Court since he began his career as a criminal defense attorney. It certainly, along with the Judge’s optimism and “can do” spirit, encouraged me.

Ted Jones, my brilliant and kind friend of forty years, was thoughtful and generous with his time. His advice, whether about law or life, was much sought after because of his wisdom. Most of all, whether he was telling a story or singing a song, he was great fun. His “one liners” constantly fill my head. My family and I feel his loss profoundly.

Dora Hancock, Judge Jones’s long-time friend and secretary, wrote:

Losing Judge Jones, my boss and dear friend, was hard. I honestly wasn’t expecting a change so soon, but one never knows what life has in store for us and in January 2013, I started a new chapter. I always remember his words, “nothing is learned over night, it takes about a year to get your arms around it, and there’s room to change it as you go along as nothing is written on stone,” but I wasn’t prepared for his passing. I had commenced many chapters in my life while working as Judge Jones’ confidential secretary.

In my new office among pictures of my family, there are also pictures of Judge Jones. One of my favorite pictures, when I look up, there he is among the other distinguished Court of Appeals Judges, with their robes, either standing or sitting in front of the beautiful fireplace in Court of Appeals Hall. As the Judge would often say, “we have come a long way.” “We certainly have,” I would say in return. I was one of his secretaries when he was in private practice at 16 Court Street, Suite 2308 with the best views of Manhattan and the Statue of Liberty.

During the 29 years I worked with Judge Jones, I was a witness to how many people he defended, impacted and mentored, including my two sons. Judge Jones’ knowledge was immeasurable and he would brighten a room with his mere presence. He was impartial and a careful thinker. During his time in private practice, as a Judge in Brooklyn Supreme and all the way to the Court of Appeals, he gave his utmost attention to every case before him.

I also remember him as an adjunct professor at City College and at St. John’s Law School, where he taught from his experience. Throughout the years students would call his chambers, send a note or he would see them at an event and they expressed how he had made a difference in their lives. Many of his former students moved on to become attorneys.

Judge Jones was a caring person, down to earth and easy to talk to. He was there for his friends, colleagues and staff when someone needed advice, a pep talk, a word of encouragement, or a shoulder to lean on. Whether you were at a bar association event, golf outing, Brooklyn Supreme or the Court of Appeals, if you mentioned Judge Jones’ name to anyone, they would have a memorable story or two about him and his dynamic personality.

Judge Jones was not only my boss; he and his family are a part of my family. As a family, we celebrated many happy events, such as births and weddings. Unfortunately, we also had to deal with many tragedies.

In recent years, a new family tradition was created. At the end of the summer, the Jones family would host a barbeque where his present and former staff got together to catch up while he cooked on the grill, the children played games, the adults would talk, some laughter in between and he would take memorable pictures. His wife, Joan, and family have continued with the tradition.

My husband and I as well as my family all agree that Judge Jones was one of a kind, a true friend and although I have wonderful memories and pictures, he is missed.

Sandra H. Buchanan, reflecting on Judge Jones and capturing how Judge Jones was remembered by others, wrote:

As of late, I have been meeting practitioners and jurists who knew Judge Jones and speak of his brilliance and humility. Judge Jones also had a fun personality, and a great sense of humor. When I speak with individuals who knew him, we are often smiling yet holding back tears. . . . In fact, most recently, opposing counsel and I were discussing the Court of Appeals, and he recalled Judge Jones. Counsel asked me if I knew him as a trial judge. And I did not. So I sat there and listened attentively. Judge Jones loved to tell stories about being in Brooklyn. And on that autumn day, I was in Brooklyn hearing a great story about him.

The general themes are always the same: he was revered, hard-working, and a consensus-builder, who had a warm, endearing personality. Although the themes repeat, the stories do vary and are never dull. It is amazing how many of us hold dear our friendships with Judge Jones, even beyond our legal community. I saw it more clearly at the services celebrating his life at Mount Pigsah Baptist Church. Working closely with him and through the testimonies of his wonderful family and his friends, this is what I take away: Judge Jones led by example; he remained rooted; and not only did he achieve, but he also lived.39

Jay Kim, on working as a law clerk in Judge Jones’s chambers, wrote:

[T]he work was challenging in light of the nature of the issues presented and the constant cycle of preparing for cases. Judge Jones, however, intuitively understood the demands of the position and afforded his clerks tremendous respect and autonomy in the management of the work load. In turn, we reciprocated that confidence by ensuring that Judge Jones was thoroughly prepared for every matter so as not to betray the trust he placed in our hands. He never imposed any additional pressure or burden on his staff, but heartily encouraged our efforts. Every submitted assignment would elicit a remark of ‘Beautiful!’ before he would offer his suggestions and edits. . . .

To those who worked for him, with him, or simply had the pleasure of knowing him, Judge Jones was a singularly unique individual. He was kind, compassionate, thoughtful and wise—characteristics that many would ascribe to the ideal jurist. Indeed, I think it is a remarkable testament to his true character when his secretary once told me that in her nearly thirty years working for Judge Jones, in both his roles as a private practitioner and a Judge, she had never seen him raise his voice in anger. That he would joke or tell stories in chambers should not be understood to mean that he treated his position at the Court with equal levity. Judge Jones approached his job with passion and meticulous care. . . . That unceasing effort to strive for justice can be plainly evidenced in a body of legal work that will remain forever memorialized in textbooks and case reporters. Judge Jones’ greatness as a person, however, is best measured by the indelible mark he impressed upon everyone he touched with his quiet humility, infectious enthusiasm and boundless generosity.”40

Juan C. Gonzalez, sharing a little bit about the lighter side of life in Judge Jones’s chambers, wrote:

As a member of Judge Jones’ inaugural class of law clerks at the Court of Appeals, I had the distinct honor of witnessing Judge Jones ‘in action’ in chambers, deep in the marbled halls of 20 Eagle Street. When not engaged in our case discussions, I and my fellow clerks relished the opportunity to listen to Judge Jones’ countless stories, never dull and always lined with an important lesson or life observation. But most memorable were what I and my co-clerks fondly remember as Judge Jones’ favorite one-liners. At the start of any confidential case discussion, Judge Jones would quip that the ‘Cone of Silence is down,’ a reference to a joke from ‘Get Smart,’ the 1960s T.V. comedy spy series; and then there was the memorable ‘flaps down, we’re about to hit the runway,’ which Judge Jones was fond of saying as he returned to chambers following case conferences on the last day of the Court’s session, a humorous reminder that it was time to head back home after a long two-week session in Albany. Last but not least was ‘Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred,’ a quote from Lord Alfred Tennyson’s 1854 poem, ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade,’ which Judge Jones frequently uttered before taking the bench for oral arguments. In Judge Jones’ presence, one was never far from his unwitting reminders to laugh once and a while.41

Douglas Tang, remembering Judge Jones’s cookouts and family gatherings, further wrote:

I fondly recall that there was no better showcase of Judge Jones’ skill, generosity, and hands-on nature than at the Judge’s many well-stocked barbeques, cookouts and family gatherings. Like his mission for justice as a respected jurist, the Judge was tireless in his pursuit to make great food for his family and friends (including driving to the Fulton Fish Market at 5:00 a.m. to buy the liveliest bushel of crabs) and would put hours of labor into preparing one of his famous recipes, like steamed blue crab or curry goat, to the savory delight of all. The Judge not only generously shared his recipes with all who were interested but, drawing from his inner sportsman, also did not shy away from trying adventurous new dishes (including untested recipes made by his law clerks which, to be sure, involved not an insubstantial degree of risk). While the time, place, and food may have varied, one thing remained constant – sharing a meal with the Judge always meant good laughs and a great time.

Clifton R. Branch, Jr., sharing some insights about Judge Jones, wrote:

It has been nearly two years since Judge Jones passed away and in that time I have thought of him often. One memory of the Judge goes back to when I first started working for him in late January 2007 in Supreme Court, Kings County. Although I had heard wonderful things about Judge Jones, I felt a little uneasy when I saw how close he and his staff (Janice Taylor and Dora Hancock) were. They had their routine down, running jokes and one-liners included, and I wasn’t quite sure if I would fit in. The Judge, sensing this, thought of the perfect way to make me feel more at ease: he light-heartedly made me the butt of a joke. The office got a good laugh and I began to feel like I was part of the team. I thought if a judge as accomplished as Judge Jones would take the time to make fun of me, everything (concerning my new position) would work out.

Shortly before he was confirmed by the Senate, I saw how intelligent and focused Judge Jones was. He worked extremely hard to learn as much about the Court of Appeals as possible. In between reviewing briefs and preparing reports on the appeals for the second half of the Court’s February 2007 session, Judge Jones, Janice, Dora and I had quite a few meetings on everything involving the Court. Judge Jones, who did not have prior experience as an appellate judge, was a quick study who asked incisive questions to expand his knowledge of the Court and the appeals process.

One great thing about the Judge was that if he did not understand something, he had no problem asking for assistance or seeking counsel. Another great thing about him was his confidence that he would, in short order, master the concept (or as he liked to say “get my arms around it”). I think his confidence, in part, came from his living through so many challenging situations.

Over the years as his clerk, I grew to admire Judge Jones for how he lived his life and went about his work. His smarts and work ethic were balanced with an excellent judicial temperament and sense of the big picture. Off the bench, Judge Jones was funny, warm and genuinely decent. He loved to get together with family and regularly invited all of his staff, even those no longer working for him, to his family functions. Once you worked for Judge Jones, you were part of his extended family and he made sure you knew it.

Some of my fondest recollections of Judge Jones concern his views on life and the law. His insights, which were always enlightening and colorful, along with the laughter we shared and the life lessons he taught me, are permanently etched in my memory. Judge Jones’ influence on me from how I deal with people to how I think about the law cannot be measured. He irrevocably changed my life for the better.

It is rare to find someone who positively and profoundly impacts the lives of many without celebrating himself. Judge Jones, through his work and the example he set, was such an individual and more. He left the judiciary and the legal profession richer through his service.

Judge Ted Jones was beloved and well respected both inside and outside the New York State court system. Although he reached the heights of success as an attorney and judge, achieving success for the sake of it was not his goal. Being of service is what drove Judge Jones always and he left a legacy of excellence and purpose. As a criminal defense attorney, he represented all clients with skill and heart. As a judge, he consistently rendered legally sound, common sense-based decisions and opinions. Moreover, his work to promote diversity and on the Justice Task Force will have a lasting impact on the criminal justice system as a whole.

Endnotes

-

Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman, Diversity Day Speech at Court of Appeals Hall (Feb. 15, 2013).

-

Id.

-

Dean Michael A. Simons, Saying Goodbye to Ted Jones, The Dean’s Docket, St. John’s University School of Law, Nov. 16, 2012, http://deansdocket.org/2012/11/16/saying-goodbye-to-ted-jones/.

-

Id.

-

Id.

-

Dennis Hevesi, Theodore T. Jones, Jr., Judge on New York’s Top Court, Dies at 68, N.Y. Times, Nov. 9, 2012, at A34.

-

Civil Service Law § 210 prohibits public workers from striking and provides alternative means for dispute resolution. Civil Service Law § 211 allows for injunctions to remedy illegal strikes.

-

This was New York City’s first transit strike since 1980’s 11 day strike.

-

N.Y.C. Transit Auth. v. Transp. Workers Union of Am., N.Y.L.J., Apr. 26, 2006, at 19.

-

Steven Greenhouse, Tough Stance, Tougher Fines, N.Y. Times, Dec. 22, 2005, at A1.

-

Vincent Bonventre, New York Court of Appeals: The Jones Factor in Criminal Cases (Part 2), N.Y. Ct. Watcher, Aug. 19, 2008, http://www.newyorkcourtwatcher.com/2008/08/new-york-court-of-appeals-jones-factor_19.html.

-

Erika L. Winkler, Theodore T. Jones, The Defendant’s Champion: Reviewing A Sample of Judge Jones’s Criminal Jurisprudence, 73 Alb. L. Rev. 1109 (2010).

-

8 N.Y.3d 449 (N.Y. 2007). LeGrand set forth the standards governing the discretion of trial courts concerning whether expert testimony on the reliability of eyewitness identifications should be admitted. See People v. Santiago, 17 N.Y.3d 661, 669 (2011).

-

Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923).

-

See LeGrand, 8 N.Y.3d at 452.

-

8 N.Y.3d 530 (N.Y. 2007).

-

See Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200 (1979); Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961). See also People v. Mendoza, 82 N.Y.2d 415, 422 (N.Y. 1993) (explaining Mapp and Dunaway hearings).

-

Bryant, 8 N.Y.3d at 533–34.

-

13 N.Y.3d 67 (N.Y. 2009).

-

Id. at 72.

-

Id.

-

19 N.Y.3d 147 (N.Y. 2012).

-

Id. at 161 (Jones, J., dissenting).

-

Id. at 161–62.

-

10 N.Y.3d 136 (N.Y. 2008).

-

Id. 153–56. The Court held that latent fingerprint comparison reports–which compare unknown latent fingerprints from the crime with the fingerprints of a known individual–prepared by a police detective who did not testify at the defendant’s trial were testimonial statements and should not have been admitted into evidence. Such reports are inherently accusatory and, here, were used to prove an essential element of the crimes charged. However, the Court held that the trial court’s error was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Court also concluded that: (1) the report containing DNA test results (raw data in the form of nonidentifying graphical information) prepared by technicians from an independent private laboratory who did not testify at trial was not testimonial and was properly admitted into evidence; and (2) reports which interpreted the DNA test results were properly admitted into evidence at trial because the reports did not directly link defendant to the crime.

-

9 N.Y.3d 1 (N.Y. 2007).

-

Id. at 10–11.

-

14 N.Y.3d 303 (N.Y. 2010).

-

Hotel 71 clarifies the law of enforcement with respect to fixing the situs of an intangible property interest, and potentially expands a judgment creditor’s ability to attach a judgment debtor’s property in satisfaction of a judgment.

-

9 N.Y.3d 481 (N.Y. 2007).

-

See id. at 491–500.

-

42 U.S.C. § 1983 is the current version of Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (one of the post-Civil War Reconstruction-Era civil rights statutes enacted by Congress).

-

556 U.S. 729 (2009).

-

See the New York State Justice Task Force Website at www.nyjusticetaskforce.com.

-

Hevesi, supra note 6, at A34.

-

Joel Stashenko, ‘Serious’ Effort Vowed On False Convictions, N.Y.L.J., July 15, 2009, at 1.

-

In 1984, the Metropolitan Black Bar Association, a unified association of African-American and other minority attorneys in New York City, was founded after the merger of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Lawyers Association, an organization in existence since 1933, and the Harlem Lawyers Association, which was founded in 1921.

-

Sandra H. Buchanan, Memories of the Honorable Theodore T. Jones: An Admired Judge, 77 Alb. L. Rev. 5, 7 (2013).

-

Jay Kim, Clerking for Judge Theodore T. Jones, 77 Alb. L. Rev. 9, 10–11 (2013).

-

Gonzalez, Judge Jones: A Memoir, Leaveworthy, Vol. III, No. 2, Summer 2013.