I am authoring my own story because it would be difficult for anyone else to appreciate the extent to which my life and career have been influenced by my family and a series of coincidences that shaped the direction of my professional pursuits. Perhaps my career journey to the Court of Appeals will encourage other young women to take advantage of opportunities that may cross their paths.

No portrayal of my life is complete without giving due credit to my family. Our history is not unlike that of thousands of southern Italians who immigrated to New York to escape poverty and bleak futures. The collective history of their struggles and sacrifices when confronted with prejudice and discrimination, and their unwavering desire to make life better for their children, is similar to the heritage shared by many Americans of Italian descent in the United States. Although the accuracy of these figures may be debatable, according to United States Census Bureau statistics, fewer than 15,000 Italian immigrants arrived in the United States in the years preceding the Civil War, and by 1880 fewer than 70,000 Italian immigrants had entered this country. Yet by 1910, the number of Italian immigrants had swelled to more than two million (over 200,000 Italians entered the United States in each of the years 1903, 1905, 1906, 1907 and 1910).1 A quarter of this influx after 1900 came from Sicily. This tide of Italian immigration receded by 1919-only about 2,000 Italians arrived in America that year.

My grandparents were representative of these two waves of Italian immigration. Each came with not much more than a valise and a hope for freedom and prosperity. My maternal relatives arrived in the 1870’s-1880’s from the Salerno region of Italy, while my paternal grandparents left Sicily as adolescents, without their parents, shortly after the turn of the twentieth century. As one illustration, my grandfather Graffeo came to the United States in 1901. His family in Palermo had saved to send his older brother to America but, shortly before the ship was to depart, he became ill and couldn’t pass the physical examination for the voyage. The ticket was handed to my 17-year-old grandfather, who arrived at Ellis Island alone and without any relatives in America to care for him. He found work as a barber and learned English. With less than a decade of the American experience under his belt, he joined the U.S. Army to fight in World War I and eventually became a sergeant. Since both of my grandfathers fought in the trenches of the European theater, they taught us to appreciate the high price paid for our freedoms.

This strong sense of patriotism was also evident in the next generation of my family. The role that Italian-Americans played during World War II is undervalued. When the United States declared war, Italians were the largest ethnic group of foreign-born in America (German-born were the next largest group).2 More than a million Italian Americans fought in World War II.3 My father was one of those who enlisted. Immediately after his final exams as a high school senior, he and his cousin joined the Army. My father trained in artillery in England and then was sent to the Normandy shore with the 731st Field Artillery Battalion, as part of General Patton’s Third Army. His battalion spent most of the war in Belgium, France and Germany, usually on the front lines battling German tanks and artillery. At 82 years of age, my father remains a proud and active member of the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars and Battle of the Bulge organizations. Last year my husband and I took my parents to visit the new World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. It was a moving experience for them to share experiences with other veterans and their families. My father’s and grandfathers’ sense of duty to country is an important chapter in our family history.

My parents met and married after the war and I was born in 1952. My father took a job as a surveyor with a highway construction firm that was building the Massachusetts Turnpike so we moved to Lanesborough, Massachusetts, a rural hamlet in the Berkshires. Despite the fact that neither of my parents knew anything about agriculture, they purchased a former dairy farm. They managed to rent the barn and fields to a farmer so I spent my early youth wandering our property, watching the cows and hanging around the cool milk house. Our house was attached to a small motel (named after me — the Victoria Motel) operated by my mother. Our family grew during our years in Massachusetts — my sisters, Andrea and Christina, were born. I attended grade school in a small schoolhouse, with more than one grade level in each classroom.

We moved to the City of Schenectady when the firm that employed my father eventually completed its project in Massachusetts and began work on another highway, the Northway, in the Capital District in New York. From what my parents tell me, I had great difficulty adjusting to city life and resented the loss of ability to roam since I was confined to our apartment and our block of upper Union Street. I knew at an early age that I would never be happy as an urban dweller. But in 1961, my father began working for the New York State Department of Transportation and from my perspective, life improved.

My parents built a modest suburban house in the Town of Guilderland, in Albany County, which became our homestead for over 30 years. They selected a great neighborhood for their four children (my brother, Paul, had arrived ). With scores of children in our age ranges, we never had any trouble gathering teams for kickball, softball or our favorite summertime pursuit — sandball fights. With both my parents employed, my maternal grandparents came from Brooklyn each summer to look after us, accompanied by our cousins. We never felt deprived that we didn’t go away to summer camp or travel for family vacations because we adored my grandparents and loved our carefree summers. Our time was spent building and defending our forts in the pine woods adjacent to our yard, riding our bicycles “no hands” on hilly rural roads, and swimming at the town park. Looking back, we were extremely fortunate to have such a wonderful childhood — it was the fulfillment of my parents’ dream to provide us with a safe and happy environment. The only one who suffered occasionally was my brother. Not only did he have to struggle as the youngest, but he was surrounded by only sisters and female cousins. To add to his pain, his best friend down the street had seven sisters. It’s no wonder that he sometimes retreated to sleep in a tent in our backyard.

I do not want to underestimate the role of women in my family and the impact they had on my development. My grandmothers were remarkable women who shared a tireless commitment to family. They were also fabulous Italian cooks, an attribute highly appreciated by our family. But they represented two different immigrant approaches to life in America. My father’s Sicilian mother never quite assimilated into American society, she did not learn to speak or read English, and she did not work outside the home. In contrast, my maternal grandmother, whose family came from Naples, had gone to work in garment sweatshops as a child to help support her family as the oldest of 13 children. During the many years she worked as a seamstress, her friends were of diverse ethnic backgrounds, so she had a broader view of the world. My grandmother believed women should have an active voice in community affairs and she proudly told us stories of having marched as a suffragist and her involvement in local politics. She was a devout Roman Catholic who attended daily mass and never missed reciting daily rosaries and novenas. While all of my grandparents and relatives possessed deep faith, it was the women in the family who toiled long hours in the kitchen to make religious holidays such special occasions.

This heritage is the foundation of my values. At an early age, I was taught the importance of what I refer to as the three Fs — family, faith and food. While my work as a lawyer and a judge has consumed a large part of my life, I am first and foremost, a wife, daughter, stepmother, niece, sister and aunt. I was indeed blessed to grow up embraced by a supportive extended family. What we lacked in material wealth was more than compensated by the good times we enjoyed together. There were no holidays or personal milestones that we did not celebrate together, and always there was superb Italian cuisine. My grandparents, aunts, uncle and cousins were not just “relatives,” they were an integral part of my life and I attribute my ambition to make something of myself to their influence.

I graduated from Guilderland Central High School in 1970. It was a significant victory for me when my parents agreed that I could attend college away from home. Up to this point, no one in my family was a college graduate and my older cousins were commuting to college. My parents had made many financial sacrifices over the years in the hope of providing their children with the educational opportunities that were not possible for them. But the cost of private colleges was unquestionably beyond our means and, as children of the Depression, my parents were adamant that we would not incur debt to finance my education. When a scholarship I was offered from Cornell University proved insufficient to match the tuition and board cost of the State University of New York, I enrolled at the State University College at Oneonta. In retrospect, my parents made wise decisions that enabled their four children to graduate from SUNY colleges and begin their careers or graduate school without being saddled with undergraduate debt.

In the autumn of 1970, I arrived at Oneonta as an elementary education major. Finding that I preferred history and political science, I changed my major to political science, with a minor in secondary social science education. Lacking funds to study abroad for my junior year, I opted for a Canadian Studies program at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. My experiences at McGill in 1973 were more meaningful than my academic studies. Residing in a dormitory that housed foreign students, I quickly realized how much Americans take freedom for granted as I listened to the stories of students from Eastern Europe. One evening, a graduate student from Czechoslovakia, then under Communist rule, was frantically pounding on my door and asking to hide in my room because “officials” were looking for her. She had attempted to send political literature home to her brother. As she hid in my closet, I assumed she was overreacting, but then a man appeared at my door, spy-like in a raincoat and dark glasses, inquiring if I knew her whereabouts. Fortunately, he accepted my denial and continued his inquiries down the corridor. On another occasion, two distraught African students announced at dinner that they had to leave the university the next day because their country’s new dictator had ordered home all students studying abroad. These episodes taught me more about life in totalitarian countries than anything I had read in textbooks.

In addition to learning some important life lessons, I also acquired a new hobby in Montreal — ice skating. Each evening at 10:00 p.m., the campus ice rink opened for dorm residents. I would have had little social life if I didn’t lace up and join in Canada’s favorite pastime. I have taught my five nieces to skate to ensure the availability of skating companions.

When I returned to Oneonta for my senior year, several professors suggested that I consider graduate or law school. Without their encouragement, I doubt I would have applied to law school. Again, cost was an obstacle so I selected the five most affordable law schools in the northeast. Then, in January 1974, I began student teaching at Norwich High School in Chenango County. I loved teaching 11th and 12th grade Social Studies, so after acceptances arrived from all the law schools that I applied to, I was uncertain about my future. Concerned about my career dilemma, my supervising teacher brought me to meet a Clarence D. Rappleyea, Jr., a Norwich attorney whose daughter was one of our students. I appreciated his encouragement to pursue a legal career but didn’t give the visit much thought in the ensuing years. I could not have imagined the influence he would later have on my career. I finally went home to break the news to my parents that I was not going to seek employment as a teacher; instead, I was headed to law school. My parents were stunned, we didn’t know any lawyers and I wasn’t even certain what attorneys actually did, but I sensed it was a meaningful way to help people. Because my family could not provide financial assistance for graduate school, I decided the only way I could afford to pay tuition was to live at home and work part-time. I therefore enrolled at Albany Law School of Union University.

My years at law school were a balancing act — I never had enough time to enjoy the experience. I juggled several jobs my freshmen year, including working as a waitress with my sister at the International House of Pancakes. For some reason, my sister Andrea made more in tips than I did, she probably had more patience dealing with the customers. Law school freshmen, however, were not supposed to have outside employment, and one fateful day, I was summoned to the Registrar’s office for a lecture about the need to devote full time to the study of law. Nice objective if you have someone paying your tuition bills. I exercised more discretion after that reprimand and stopped changing into my waitress uniform in the school locker room.

As a second-year student, I decided to gain experience working in a law firm in order to find out what the practice of law was really about. There were few female attorneys in litigation practice in Albany in the mid-1970’s and some firms didn’t hesitate to announce that they were not interested in hiring women. But the lawyers at Tate, Bishko, Miller and Ruthman, Esqs. were a different breed. I was so ecstatic to be called for a second interview that I didn’t question why the head of the firm, Frank Tate, Jr., a former judge, asked me to handwrite a paragraph. He then analyzed my handwriting and I was startled how accurately he described my personality and habits. I didn’t know at the time that he was a certified handwriting analyst. When I was offered the position, I silently thanked my mother for making me practice my cursive letters as a fourth grader.

For the last two years of law school, I attended classes in the mornings or evenings and worked afternoons at the law firm. There were eight male attorneys in the firm when I joined the practice as an associate after taking the bar exam. In February of 1978, I was admitted to the New York Bar through the Appellate Division, Third Department, and to the Federal Bar in the Northern District of New York. My grandfather Graffeo sent me a dozen red roses when he learned of my bar passage. My first vacation as a lawyer was spent with my 92-year-old grandfather at Disney World in Florida. It was his first airplane trip and we rode all the park rides together, except Space Mountain because the attendant told him he was too old. It was a gift to spend that time with him, my grandfather passed away a year later.

At the law firm, I worked primarily with two talented litigation partners, Rex S. Ruthman and Peter Bishko. They taught me about the practice and business of law. My gender was not an issue with them and I was encouraged to get experience in the courtroom. Within a short time after my admission to the bar, I tried my first case in Supreme Court in Columbia County and quickly learned that litigators must be resourceful. My clients were property owners who had brought an action seeking to have a gravel road that provided access to their parcel declared a public thoroughfare. If the road was declared a public highway, the value of their acreage would increase and the town would assume responsibility for snow plowing and maintenance. This would eventually render their property more attractive for development, a prospect that fueled a neighbor’s opposition.

Then-Supreme Court Justice Roger J. Miner (now a Senior Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit) presided at the trial. I lined up my witnesses, mostly former residents and town highway superintendents, all of whom I hoped would testify to continuing horse and vehicular traffic on the road. One witness was an elderly dairy farmer who no longer drove and wouldn’t leave his farm until his chores were completed. So early one morning, I found myself standing in his cow barn, dressed in my new suit and pumps, trying to avoid stepping into manure as we discussed his testimony. He finally disconnected the milk pump and we drove to the courthouse in Hudson. I thought he was a credible witness B a true working farmer in his overalls. Despite my best efforts, Justice Miner determined that our proof was insufficient to meet the public use and town maintenance requirements of the relevant statute. I also learned another valuable lesson: get a retainer before trying a case. My clients refused to pay my fee after we lost.

Women lawyers were not often seen in the courtrooms of the Capital District in the late 1970’s. I experienced subtle and not so subtle disparate treatment. I was trying a case in federal court against a bank, represented by a tall, stately former judge. During his opening statement to the jury, he kept referring to me as “his little friend” in an attempt to diminish my effectiveness. But at the conclusion of my direct case, he got worried and offered me a settlement larger than what my client had indicated would make him happy. Justice prevailed.

I was permitted to handle my cases to conclusion, including appeals. In 1981, I argued a case in the Court of Appeals on behalf of a contractor challenging a State Department of Labor prevailing wage claim.4 I fared better this time — we were successful and I got paid. My experience in the Court of Appeals as a young lawyer was terrifying but invigorating.

It soon became apparent to me that the law firm was going to disband due to disagreements among the partners. This was unfortunate because I had great respect for the lawyers I worked with and they had allowed me great leeway in developing my legal skills. Wanting to remain on good terms with all factions in the firm, I decided to try government practice until I saved enough money to finance the opening of my own law office. Learning of a job opportunity as an assistant counsel at the New York State Division of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse, I applied for the position although I was unfamiliar with the disease of alcoholism. But I was aware of the devastating effect alcoholism had on the families in divorce, criminal and juvenile delinquency cases. I worried about leaving private practice, but I had the good fortune to work at the Division with Karen K. Peters, its Counsel. We were responsible for the legal affairs of the agency and its state-operated alcohol treatment centers. Our duties also included drafting legislative proposals, such as raising the legal purchase age for alcohol in New York to 21 years of age, securing health insurance coverage for outpatient treatment of alcoholism and establishing credentials for alcoholism counselors. I represented the agency at administrative hearings, provided legal counsel to non-profit alcoholism treatment programs around the state, and handled administrative, budget and personnel legal issues. Karen Peters was a superbly organized attorney and administrator, keeping track of the work of each bureau. She set a fine example as an effective manager — something law schools don’t teach. When Governor Hugh Carey’s administration was drawing to a close, she resigned to run for a Family Court judgeship in Ulster County. I knew she would do a splendid job on the bench, but I found the idea of running for office, particularly as a female candidate, daunting. She won the race and was a Family Court Judge until she became the first woman to be elected to Supreme Court in the Third Judicial District.

As Governor Mario Cuomo began appointing new executive staff at the Division, I decided it was time to change jobs. I was beginning to recognize that life is a series of unexpected coincidences that we need to take advantage of despite a reluctance for change. While contemplating a job offer from an Albany law firm, the Division sent me to the Pentagon to participate in an alcohol server training program for military personnel who operated officers’ clubs. While lecturing on “dram shop” liability — the potential liability of servers dispensing alcohol to intoxicated persons who subsequently injure third parties — I received a message to contact Assemblyman Kemp Hannon. He asked if I was interested in serving as floor counsel for the Assembly Republicans in the State Legislature. Several years earlier I would have declined such an offer since I knew little about the legislative process and even less about politics. But I had gained confidence from my prior career shift, and saw the offer as an opportunity to learn how law was made in New York. When I went to interview with Assemblyman Hannon, he introduced me to the Assembly Minority Leader, the Hon. Clarence D. Rappleyea, Jr. — the Norwich attorney that I had consulted about law school a decade earlier. In February 1984, I became Counsel to the Hon. Kemp Hannon, Minority Leader Pro Tempore of the New York State Assembly. Among my many duties, I compiled a weekly floor calendar for Republican leadership, which entailed reading all the bills scheduled for a vote in the Assembly Chamber, summarizing the proposals and developing debate points. The job was unquestionably demanding since Assemblyman Hannon was a skillful lawyer from Garden City who would quiz me on the details of legislation in his role as floor leader and principal debater for the Republican Conference. I also acted as parliamentarian for the Minority and had to devise ways to use the Rules of the Assembly to the political advantage of the Minority.

I spent ten exciting years working in the Legislature and learning the business of politics, including the mechanics of campaigns. Eventually I became Chief Counsel to the Assembly Minority Leader, serving in that capacity until Clarence Rappleyea retired from the Assembly in December 1994. I couldn’t have asked for a better mentor on public policy, governance and state finance than “Rapp” Rappleyea. I believe I was the first woman to attain the title of Chief Counsel to a statewide legislative leader. At times I was the only woman at the negotiating table with the Governor and his senior staff, the four legislative leaders — the Temporary President of the Senate, the Minority Leader of the Senate, the Speaker of the Assembly and the Minority Leader of the Assembly — and their counsels and budget directors. It was reminiscent of my days in an all-male law firm and I learned to adjust to the culture of the Legislature.

In 1985, I married Edward E. Winders and became a stepparent to his daughter and son. My husband owned a civil engineering firm until I was appointed to the Court of Appeals, at which time he decided to alter the course of his professional pursuits. Finishing his graduate studies and dissertation, he obtained a PhD. in Political Science and now heads a consulting firm engaged in democracy training in developing countries. He recently returned from a five-week U.S. State Department project in northern Uganda aimed at helping local officials apply for aid so they can access needed services in hopes of curbing the devastating violence and poverty that plague that region of the country. He is a remarkable person. I am very proud of his courage and tenacity in changing his career and he’s doing his part to make our world a better place to live.

My tenure on legislative staff came to an end just as George E. Pataki, a former Member of the Assembly Minority and State Senate, was preparing to take office as Governor. The incoming Minority Leader in the Assembly, the Hon. Thomas Reynolds, was from Erie County and he kindly arranged for me to meet with the newly-elected Attorney General, Dennis C. Vacco, also from Erie County. Fate struck again and Attorney General Vacco appointed me to serve as Solicitor General, a job that I consider to be the premier appointive legal position for a lawyer in government service. Management of the State’s federal and state appellate caseload was a weighty responsibility, but the attorneys in the Appeals and Opinions Bureau were consummate professionals. We handled appellate litigation involving any Executive state agency in the Appellate Divisions, the Court of Appeals, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court. During my tenure, we filed a writ of certiorari petitioning the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case of Vacco v. Quill, a constitutional challenge to New York’s criminal statute banning assisted suicide. The case had national implications because so many other States had similar penal statutes. I was able to garner considerable amici support from other Attorneys General and interested parties across the country. I left my post to run for a judgeship before the case was argued at the U.S. Supreme Court by Attorney General Vacco, but my able Deputy Solicitor, Barbara Billet, took over the brief and management of the case. New York secured a reversal, upholding the right of a State to determine this issue by legislative action.5

As a manager in the Department of Law, much of my time was consumed by administrative matters. From my years working in the Legislature, I knew that state government is all about funding. When I began as Solicitor, the appellate attorneys were not equipped with desktop computers, which meant lawyers had no immediate access to electronic legal research. We were litigating against some of the finest lawyers in New York and the country and my staff was writing appellate briefs in longhand and had limited use of a central computer for legal research. This was deplorable and inefficient. The Attorney General recognized the need to modernize the Department and undertook the difficult task of restructuring an inadequate budget. And I got involved in the State’s bidding process and negotiations with Westlaw, Lexis and other legal research firms in an effort to control the cost of providing electronic research to the hundreds of attorneys working at the Attorney General’s Office. When I left the Department in September 1996, each of the attorneys in Appeals had a desktop computer, with access to electronic legal research. These are the type of administrative challenges unique to government.

In the summer of 1996, a new career challenge arose. The Chair of the Albany County Republican Committee, George Scaringe, inquired if I had any interest in running for a judgeship and I was uncertain how to answer — it had always seemed an unattainable goal for me. Shortly after our conversation, the Hon. Lawrence Kahn, a Supreme Court Justice sitting in Albany County, was appointed a Federal District Court Judge, thereby creating a judicial vacancy. Events moved rapidly and by August 1996, I resigned from the Attorney General’s office, was nominated by Governor Pataki and confirmed by the State Senate to fill the vacancy. In what seemed surrealistic, I found myself a candidate for nomination and election for Supreme Court in the Third Judicial District.

There were other experienced and viable candidates for Supreme Court that summer so I can’t fully explain my good fortune. I think a good part of it was attributable to luck. I had worked a decade in the Legislature, becoming acquainted with many elected and party officials in several political parties. Certainly, the many campaign cycles in which I volunteered to assist candidates had brought me into contact with political leaders around the State. I also like to think that I had garnered a reputation for being a conscientious, fair and hard-working lawyer.

When I speak to law students and new lawyers, I use the confluence of factors that operated in my favor in 1996 to stress how important it is to be diligent in building your reputation and treating all people with respect. Who could have foreseen that an attorney I briefly met with in Norwich years earlier would become a statewide legislative leader and I would find myself on his staff? That a freshman member of the Assembly Republican conference I worked for would become a State Senator and subsequently be elected Governor? Or that my supervisor at the Division of Alcoholism, Karen Peters, would become a judge, be appointed to the Appellate Division and would encourage me to pursue a judgeship? We never know how the people who cross our paths will later influence our lives.

In the autumn of 1996, I ran as one of six candidates seeking three Supreme Court positions in the Third Judicial District, which encompasses seven counties, Albany, Columbia, Greene, Rensselaer, Schoharie, Sullivan and Ulster. It was a hotly contested race and I had no public name recognition, having just been appointed to the bench, while four of the other candidates were incumbent judges and one was a popular District Attorney. It was an expensive and grueling campaign, I worked days at the courthouse and campaigned evenings and weekends. Due the size of the judicial district, there were frequently long hours of travel required for campaigning, so I wouldn’t return home until after midnight. Once home, my husband would review all the tasks I still needed to accomplish in the campaign plan.

I thought I understood what it took to be a candidate in a contested race since I had spent a decade participating in Assembly races around the State. Was I ever wrong. It was more difficult than I imagined to give speech after speech, to be constantly scrutinized, and to approach strangers and ask for their vote. I couldn’t have succeeded without the unwavering support and assistance of my husband who oversaw my campaign operation, and family and friends who worked on my behalf, distributing palm cards, stuffing envelopes, driving around planting my road signs, making phone calls and doing all the mundane tasks that constitute a campaign.

It was also a learning experience. I was surprised how opinionated voters were about our judicial system and the distinct concerns expressed by attorneys in different parts of the judicial district. I became a better judge because of my experiences on the campaign trail, I acquired an understanding of how to treat litigants and jurors, what lawyers felt were important attributes of a good judge and what people felt were inefficiencies in our court system. The only negative, and it was a major negative, was the constant need for campaign contributions. Financing a campaign is a troubling and difficult hurdle for any candidate for public office, but especially for a judicial candidate. But my finance committee managed to raise the funds for media advertising and a mail program.

It was a nail-biting race for me and I was never confident that I would win one of the seats, despite the unique strategy of the Republican Party in presenting three female judicial candidates that year. Election night was depressing. I had expected to lose in my home county since voter enrollment in Albany County was heavily Democratic. But my margin of loss was greater than we anticipated so my family and I left headquarters that evening expecting a defeat. In the middle of the night, the telephone rang and I learned that it appeared that I had won one of the judgeships on the strength of votes in the other counties. It took weeks for a recount to be completed and when the results were declared final, Mary O. Donohue (currently the Lieutenant Governor of New York State) was the top vote getter and I came in second. My swearing-in ceremony was a glorious occasion for my family — I only wished that my grandparents could have been there to share our joy.

There is nothing like sitting on the Supreme Court bench. During my tenure on the trial bench, I was assigned to trial terms in four counties, and when needed, I’d take trials in other counties in the judicial district. It was simply a terrific and rewarding job, with a wide variety of cases, the opportunity to help litigants resolve their disagreements and the ability to do what’s right. I enjoyed the hands-on interaction with lawyers and litigants. There is a real potential to make a difference in people’s lives. I saw this most clearly in matrimonial cases and in proceedings seeking to have conservators or guardians appointed for elderly or disabled persons. I’d conduct matrimonial conferences that would span hours, but it was time well spent if the parties could reach a fair and appropriate settlement and avoid the additional acrimony certain to arise at trial. As a former law guardian in Albany Family Court, I believe that children are always affected when their parents are engaged in legal battles, and that years of divorce or custody litigation inevitably give children a sense of insecurity and uncertainty. For this reason, I found that the work I did outside the courtroom was just as important to our justice system as my function in presiding over trials.

In March 1998, I was appointed by Governor Pataki to serve as an Associate Justice of the Appellate Division, Third Department. Before applying for this position, I debated the pros and cons of leaving the trial bench. I not only loved the work, but I also felt a responsibility to women in the Bar. I was the only woman on the Supreme Court trial bench in the Third Judicial District at that time (Karen Peters was serving on the Appellate Division). But I decided that possible elevation to that appellate court would also help promote the role of women in the legal profession — a cause that I had long been interested in as a past president of the Capital District Women’s Bar Association and a member of various judicial screening committees.

The Appellate Division, Third Department handles civil and criminal appeals from 28 counties so the 10 judges on the court carry a heavy caseload. Under the leadership of the Presiding Justice Anthony V. Cardona, the Court decides close to 2,000 cases a year. I have deep affection and respect for my former colleagues, they are dedicated judges who deserve far more recognition than they receive for their efforts. The wonderful collegiality on that Court was an unexpected bonus. As another example of unpredictable coincidence, the Hon. Karen Peters and I were again colleagues during my service on that Court.

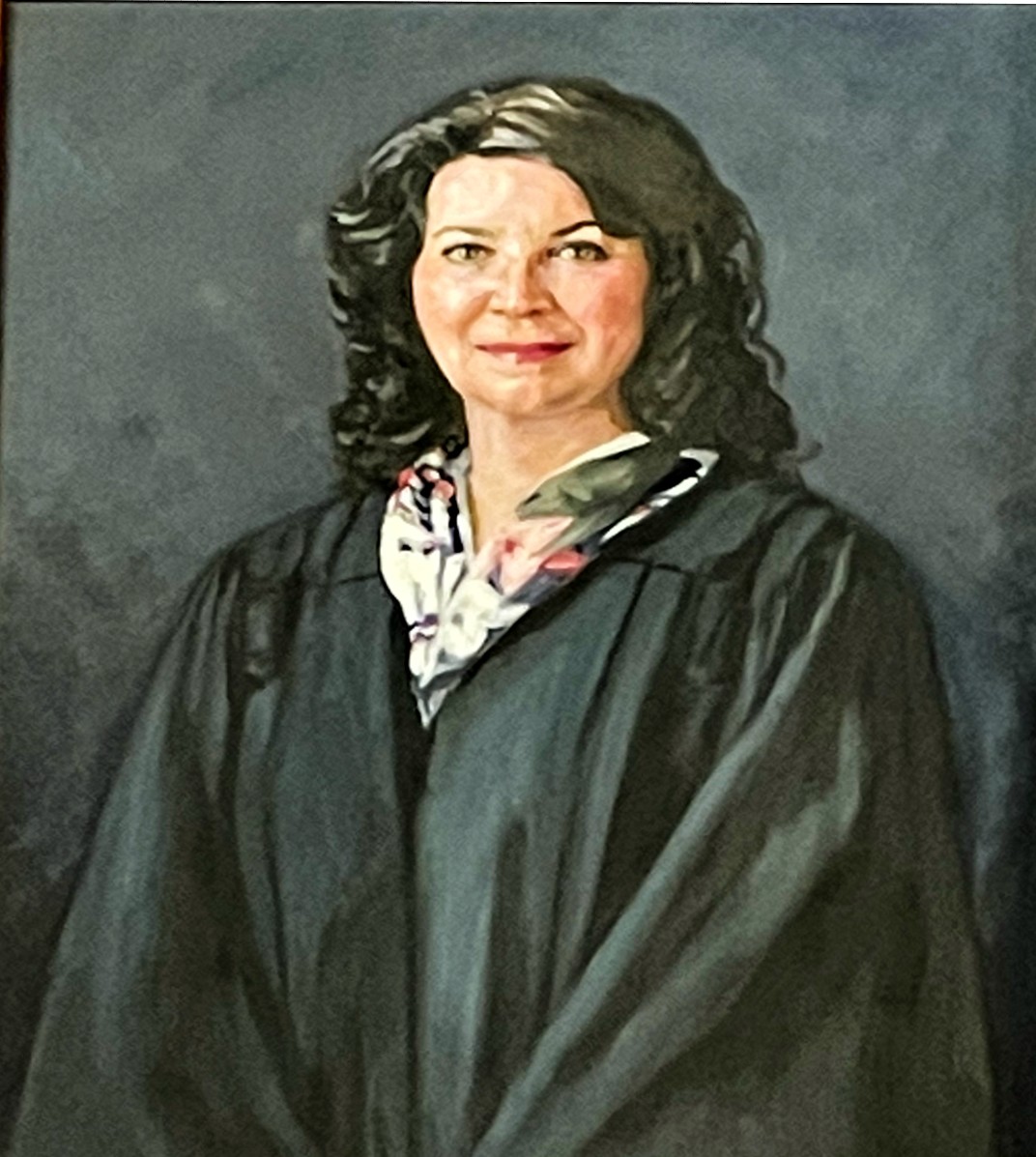

I took a bold step in the Spring of 2000 and applied for a position on the Court of Appeals. The screening process brought me into contact with many people that I had previously had occasion to meet during my years on staff at the Legislature and from my work with various bar associations and civic groups. I was thrilled to make the list of persons recommended to the Governor but I told my family not to get too excited. Good news arrived and I was nominated by Governor Pataki and confirmed by the State Senate on November 29, 2000, with my husband and parents by my side in the Senate gallery. I was glad they were included in the photo that appeared in our local newspaper because my family deserved to share in that achievement.

What could be more awesome than climbing the front steps of the impressive Court of Appeals Hall and entering its magnificent, historic courtroom for the first time as a member of the Court? I sat for oral arguments beginning in January 2001. Although change always brings some degree of anxiety, from my viewpoint, my assimilation into the culture of the Court went smoothly because of the generous assistance and warm collegiality of my new colleagues — Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye and Judges George Bundy Smith, Carmen Ciparick, Howard Levine, Richard Wesley and Albert Rosenblatt. I had come to expect the unexpected in my career and coincidence struck again, I had worked with Judge Wesley when he was a Member of the Assembly in the 1980’s. As I enter my fifth year with the Court, there have been changes in the Judges serving on the Court, but the work of the Court continues seamlessly. I am proud of the traditions of our Court and that ours is a collegial bench due to the steady guidance and leadership skills of our incomparable Chief Judge, who encourages the full expression of opinion in conference. I am honored to have this opportunity to serve the people of our great State.

Despite the time demands of our caseload at the Court, I do my best to remain active as a volunteer in civic organizations since I believe it’s important to give back to one’s community. For almost 20 years, I’ve been a member of the Zonta Club of Albany, a chapter of Zonta International, which strives to advance the status of women around the world. I am also a member of the board of directors for the alumni associations at SUNY Oneonta and Albany Law School. Both institutions have been wonderful to me and I take every opportunity that’s offered to meet with their students to encourage them to keep working toward their goals. As a founding member and past president of the Capital District Women’s Bar Association, I am always interested in promoting diversity in the law and on the bench. My other professional affiliations include the New York State Bar Association, the Albany County Bar Association and the Greater Capital Chapter of the Italian-American Bar Association.

Before concluding, I must give recognition to the people who have worked at my side during my judicial career. If nothing else, I am proud of my ability to recognize talent and character. I am grateful for the steady assistance of Elaine Heffron, who has been my secretary since I entered the judiciary. My law clerk in Supreme Court and for a time in the Appellate Division was Christopher O’Brien, who went on to become an Assistant Counsel in the Governor’s Counsel’s Office and is now Counsel for the State Department of Taxation and Finance. I then had the wisdom to lure one of the former appellate attorneys from the Department of Law, Lisa LeCours, and she has remained my principal court attorney since I was on the Appellate Division. She was joined in Chambers by John McManus, now in litigation practice in Albany, and Margery Corbin Eddy, who has returned to work on central staff of the Court. I am currently fortunate to have Matthew Dunn and Stephen Sherwin as my law clerks. I owe all the attorneys who have labored with me a huge debt of gratitude for their commitment and dedication to the pursuit of justice and for their support and loyalty.

Progeny

When I married Edward E. Winders in 1985, I became a step-parent to Jennifer and Eric Winders.

Comment by Lisa Lecours, Principal Law Clerk

Having served as Judge Graffeo’s principal law clerk since March 2000, it is my honor to supplement her biography with a discussion of some of the decisions that reflect her tenure on the bench to date. Before addressing her written opinions, however, I must take this opportunity to speak more broadly about Judge Graffeo as a Judge, a mentor and a person. Anyone who has worked with Victoria Graffeo will attest to her extraordinary work ethic and her unwavering commitment to excellence. What might not be apparent, but is well known to those who work closely with Judge Graffeo, is that her drive stems from her commitment to the individuals served by the judicial system, the litigants whose lives are affected by the decisions reached. I know I speak for all of her law clerks, past and present, when I say that it has been a great privilege and incomparable learning opportunity to serve Judge Graffeo. We have been deeply affected by Judge Graffeo’s compassion for the people served by the court system, her collegial approach to decision-making and her devotion to her family, friends and colleagues. On a more personal note, Judge Graffeo has been an extraordinary mentor to me and to her other clerks. She has generously shared her time and her insight, providing advice and other assistance in matters that go well beyond the development of our legal skills. As lawyers, we could have no better role model.

When Judge Graffeo speaks of her tenure on the trial bench, she often talks about a case that had a significant personal impact on herCthat highlighted the important role of the judicial system in the lives of real people. It is not a case that involved unusually complex legal issues or large sums of money, nor was it viewed as significant by the press. But, to Judge Graffeo, it is one of the most important cases she ever presided over because it provided an opportunity for the judicial system to fulfill its promise of protecting the interests of those among us least able to protect themselves. The case, Matter of Katherine D., involved an Article 81 proceeding for the appointment of a guardian of a 61-year-old woman. Katherine D. had been discovered at her home lying on the floor amid trash and animal and human excrement. Her many pets, including farm animals, roamed throughout her home, which was in such a state of disrepair that it was later condemned by the local health department. Katherine D. had lost the ability to walk, was incontinent and suffered from dementia. Her husband, who was living with his daughter, periodically visited the house to bring his wife food, which he left in a bowl on the floor, but for most of the day Katherine was without assistance.

Deploring the conditions in which Katherine D. was found, Judge Graffeo decried the fact that her relatives knew of her plight but had taken no action to alert authorities or otherwise provide her with adequate assistance. It was the court system that rescued Katherine from this predicament. Then-Justice Graffeo conducted a hearing, met with Katherine’s family members and appointed an Article 81 guardian. Katherine was eventually placed in a nursing home where she received medical care and physical therapy.

The compassion with which Judge Graffeo approached Katherine D.’s case is emblematic of her judicial philosophyCno matter how complex the legal issues may be in a case, she never loses sight of the people impacted by the court’s decision. At oral argument, she will often ask litigants about the practical effect of ruling one way or the other. Not one to become lost in abstractions, Judge Graffeo always strives to appreciate the ramifications of each case to make certain that the Court reaches a fully-informed and just decision. She views the development of the law not as an end in itself but as a tool to promote justice.

Her Court of Appeals opinions reflect this principle. For example, the first opinion Judge Graffeo wrote for the Court involved a criminal case, People v. Kassebaum (95 NY2d 611 [2001]). In this groundbreaking decision, the Court explored the bounds of New York’s territorial jurisdiction over the prosecution of criminal conduct that occurred partially inside and partially outside the state. The Court held that a defendant who was offered a quantity of heroin and tested samples of the narcotic in a neighboring state was properly prosecuted in New York for attempted possession of a controlled substance in the first degree based on the significant conduct that occurred in this state. In the unanimous writing, Judge Graffeo did more than communicate the Court’s holding, she described the breadth and nature of defendant’s criminal conduct in this state to demonstrate that the Court’s conclusion that prosecution in New York was appropriate was a just result.

Three years later, Judge Graffeo wrote a significant decision applying the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) to a lead paint abatement law adopted by the New York City Council (see Matter of New York City Coalition to End Lead Poisoning, Inc. v. Vallone, 100 NY2d 337 [2003]). The local law was adopted in 1999 after tenant and environmental organizations brought litigation to compel the City to enforce the provisions of the existing lead paint abatement law that had been in effect since 1982. Faced with growing public concerns over the health risks associated with the removal of intact lead-based paint, the focus of the City’s 1999 legislation was the removal of peeling lead-based paint in dwellings housing a child under the age of six years (the prior law had applied to dwellings housing a child under the age of seven). Writing for the Court, Judge Graffeo concluded that, however laudable the aim of the 1999 legislation, the local law was invalid because the City had not complied with SEQRA, having failed to submit sufficient documentation establishing that it had appropriately analyzed the environmental impacts of the new approach, particularly the effect of excluding lead dust from the definition of a lead-based paint hazard and the removal of six-year-old children from its ambit. In reaching that result, Judge Graffeo was careful to explain the deficiencies in the approach taken by the City Council so that it would be able to correct the errors in subsequent legislation. Ever practical, she went beyond merely articulating the Court’s result and crafted the decision to ensure that it would assist the litigants and the public.

In 2005, Judge Graffeo wrote an extensive, scholarly opinion in a case sent to the New York Court of Appeals by certified question of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. In Capitol Records v. Naxos of America (4 NY3d 540 [2005]), the Second Circuit asked this Court to address whether there is common-law copyright protection in New York for sound recordings made prior to 1972. To answer the question, Judge Graffeo detailed the history of the development of copyright law from the 15th Century forward, a research exercise that she relished. The Court ultimately concluded that New York law provides copyright protection to such recordings, which protection will continue until it is preempted by the Federal Copyright Act in February 2067. Although the case involved a complicated and little-known area of the law, Judge Graffeo took care to explain the derivation of New York law so that the Court’s holding would be understandable to a variety of audiences, including the litigants, the recording industry and the public.

As this limited sampling of decisions indicates, Judge Graffeo moves with ease from one area of the law to another, never compromising her commitment to assisting the Court in reaching a just decision and in articulating its holding in a concise and cogent manner. I am certain that she will continue to serve both the Court of Appeals and the public with distinction for many years to come.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Published Writings Include:

Robert H. Jackson: His Years as a Public Servant “Learned in the Law,” 68 Alb L Rev 539 (2005).

New York Court of Appeals Round-Up, Federation of Bar Assns, Fourth Judicial District, 2003 Continuing Legal Education Program (2003).

A View From the Bench, New York State Bar Assn. Continuing Legal Education Program on Legislative and Lobbying Trends (2002).

Women Trailblazers in the Law in Albany County, Albany County Bar Assn, Centennial 2000, 14 (2000).

Endnotes

- Iorizzo and Mondello, The Italian Americans, 285 (1980), compiling data from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, A Statistical Abstract Supplement, Historical Statistics of the U.S. Colonial Times to 1957, 56-57.

- Panunzio, Italian Americans, Fascism and the War, 31 Yale Review no. 4 (1942).

- di Franco, The Italian Americans, 66 (Chelsea House Publs. 1988).

- Schultz Constr. v. Ross, 53 NY2d 792 (1981).

- Vacco v. Quill, 521 U.S. 793 (1997).