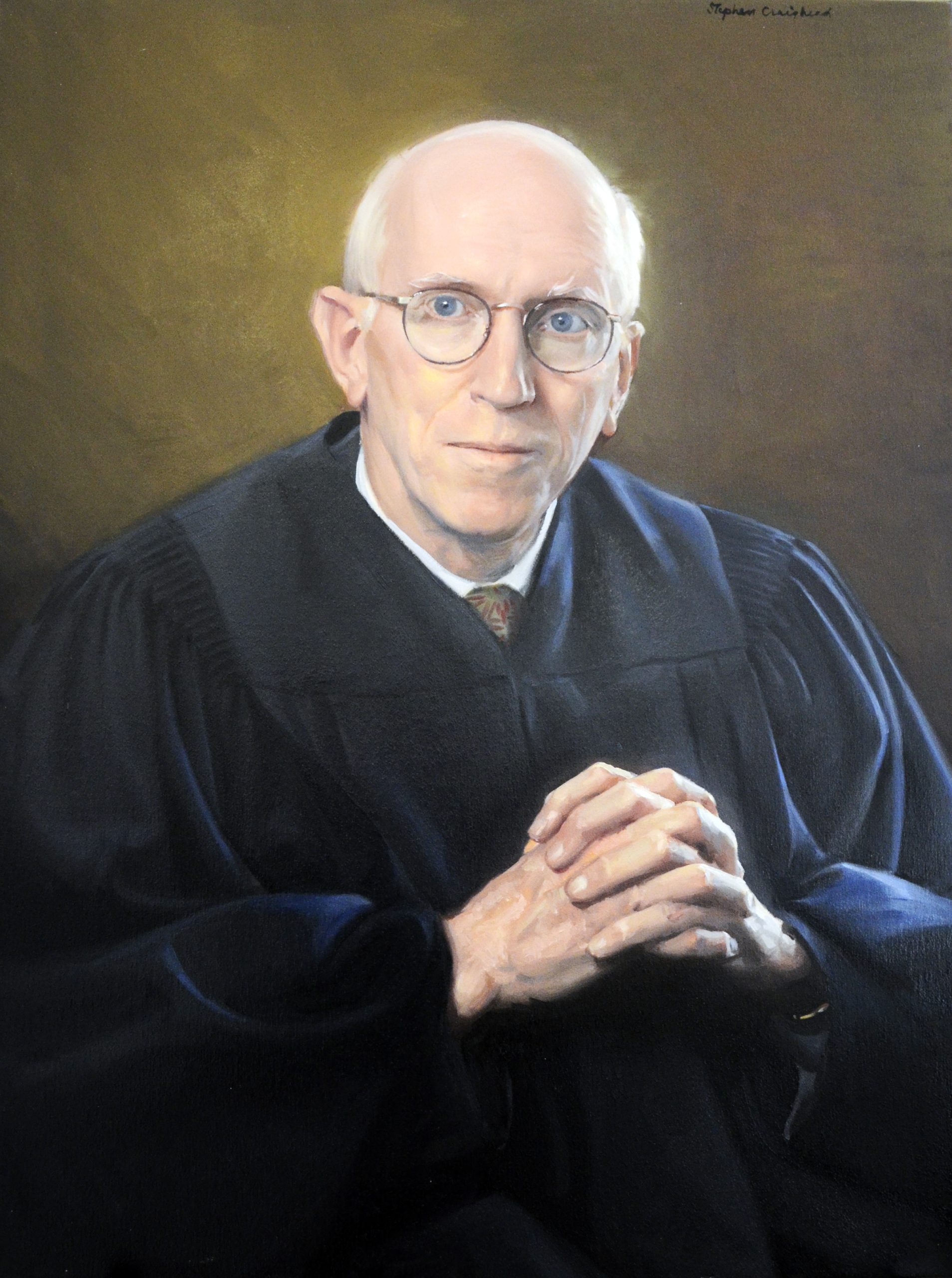

Robert Smith’s nomination to the New York State Court of Appeals in November 2003 came as a shock to many court observers, who quickly dubbed him “the stealth candidate.”1 Without any political background, Smith would also become the first non-judge in 20 years to rise directly to New York State’s highest court. When asked to reveal the secret to his own success, he is, characteristically, succinct: “I worked hard and did a good job for my client.”2 This explanation, however, is only the end of quite a long story. In fact, throughout his legal career, Judge Smith has demonstrated an extraordinary talent for the law and an honest enjoyment of its practice, qualities quickly recognized by those considering him for the bench. As one commentator remarked at the time of his nomination, “He’s just someone who is loaded with the kind of merit you want for the high court.”3

Born on August 31, 1944, Robert Smith grew up in Lenox, Massachusetts and, after his parents separated in 1952, in Westport, Connecticut. His father, also named Robert, was a novelist and nonfiction writer. Although he possessed a charisma and generosity which attracted everyone he met, Smith Sr. was also a naturally shy and quiet man. He loved solitude, spending weeks at a time alone in his cabin in the Maine woods. Smith’s mother, Janet Katz, was also a writer and literary critic. Although a kind and devoted mother, she struggled with mental illness throughout her life and could often be highly emotional. Politically, both mother and father could be most accurately described as socialists. Their fierce intellectual independence made them too radical for the average liberal but also unwilling to accept the dogma of the American Communist Party. Both were atheists and, according to her son, Janet Katz “had as little religion as anyone I have ever seen.”

Raised by two strong and colorful personalities, Smith was a mild-mannered and bookish child. In contrast and perhaps as a response to his mother, he has sometimes been described as compulsively calm. Although as a young adult he shared his parents’ political and religious views, he also shared their strong independent streaks and quizzical intellects, almost ensuring that he would eventually come to question them. The law, and particularly the drama of the courtroom, always had a romantic appeal for Smith. When he was 12, he and his mother left the United States to spend a year in Cambridge, England. On the day of his departure, he was given a book of criminal trials, Defender’s Triumph, which he finished before the boat landed and which he has kept to this day.

Always a strong student, Smith went to Stanford University in the fall of 1962 and graduated with highest honors after only three years. Despite the high quality of the education, college was not the great social experience he had hoped for. He felt a little out of place among his classmates, whom he remembers as being generally much tanner and taller than himself. He decided to return to the east coast after college, where he would attend Columbia Law School.

At the time he entered law school, Smith had no plans to become a practicing lawyer; his interests lay in politics. As he explains the decision: “Franklin Roosevelt – whom I was raised to worship – went to law school, so I was going to law school.” In fact, Smith’s quiet demeanor and contrarian tendencies made him an unlikely politician. The highest office he ever attained was treasurer of a West Side Democratic political club. Luckily, in 1967, as Smith was running for president of the club, his interests were diverted when he met Dian Goldston, his future wife, who was horrified by the group’s petty infighting. The choice was simple: “It became obvious I could not continue a relationship with Dian and also continue a relationship with politics, and I wisely decided that the relationship with her was more important.”

While at Columbia, Smith’s interest in politics was quickly replaced by a newfound passion for the law. “I just took to it from the day I walked in,” he recalls. He was inspired by his talented first-year professors, including Alan Farnsworth, Albert Hill and Marvin Frankel, and found that the questions were more focused than those in college and more likely to have an answer. He chose to take classes in all areas of the law, exhibiting a career-long eagerness to know every aspect of an issue. His passion was matched by a natural aptitude for the material; Smith was editor in chief of the Columbia Law Review and graduated first in his class in 1968.

Upon graduation, Smith joined the New York law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, where he was assigned to the corporate division. Not having lost his childhood fascination with the courtroom, however, he soon requested a transfer to litigation. “The whole feeling of combat, of winning and losing,” he explains, “the idea just appealed to me. It came naturally.”

Once in the litigation department, Smith had the opportunity to learn from some of the top litigators of the day. In addition to several of the partners, he credits Jay Greenfield, a senior associate at the time, for much of his development. A demanding and critical man to work for, he recalls, Greenfield “made me from this very callow, sort of irresponsible, self-indulgent kid, to a really disciplined, committed lawyer.” In his first major trial, arising out of the 1963 salad oil swindle, Smith worked under Arthur Liman, who gave him his only lesson in the art of cross-examination: “I try to figure out what a witness has to give me and I try to make my questions very tight.” The rest, Smith claims, is practice.

Over his next 35 years at Paul Weiss (27 as a partner), Smith would have many opportunities to practice. He quickly became a skilled legal writer and thinker. However, he had his most fun – and was most fun to watch – in the courtroom. His forte was the expert witness. With his stubborn insistence on knowing everything, Smith would pore over the details of an opposing expert’s calculations, making him a dangerous cross-examiner. In one exchange, Smith suggests that an expert overestimated the weight of a falling façade:

Q: If you look again at Exhibit 66 that I showed you there –

A: Yes.

Q: What is in between the baluster?

A: Air.

Q: Air is not terribly heavy?

A: Correct.

Q: You made an allowance for that in your calculation?

A: No.4

At other times, Smith would challenge a witness in plain English, making it appear to the jury that the expert was hiding a ridiculous position behind professional jargon. He once demanded of a criminal psychologist: “And your generalized feeling is that child abuse is a child’s fault, right?”5

Much of Smith’s work was in complex corporate litigation. As a young partner he again worked with Liman on the Becton Dickinson takeover case and in the late 1980s he represented the Air Line Pilots Association in their bid to take over United Airlines. He also worked pro bono on three death penalty cases, two of which brought him in front of the Supreme Court. Smith’s favorite cases, however, were not necessarily those involving the most money or the most media attention. He enjoyed new challenges and new opportunities to get into a courtroom, no matter what the stakes.

At the same time as he was establishing himself as a skillful litigator, Smith was also moving further and further away from the ideology of his childhood. The change in his politics had begun with a visit to the Soviet Union in 1961. He had been raised to harbor a romantic fondness for the Soviet Union and expected to be attracted by his visit. Instead, he was disturbed by the oppressive political climate as well as the severe economic conditions. Over the course of the next several decades, Smith’s politics would slowly shift right. In 1984 he would vote for his first Republican President, Ronald Reagan. No longer able to find certainty in politics, as his parents had, Smith also began to feel the need for another anchor in his life. This need became acute in 1974, when his father-in-law died suddenly, leaving behind a widow already very sick with multiple sclerosis and putting a severe strain on Dian as well as her husband. Smith, who had previously been a Protestant in little more than name, began attending church more regularly. This slowly grew into a serious commitment, and today he teaches Sunday school at his local church.

Although Smith was happy at Paul Weiss for many years, the fit was not perfect. By 2000, he found that he was not getting the quantity or quality of cases he would like and felt trapped in his practice at the firm. His first ambition was to become a judge. After years of trying to convince others how the law ought to be interpreted, he felt ready and even eager to become part of the decision process. Unfortunately, getting a judicial appointment often required, if only briefly, entering the political sphere, where Smith was far less comfortable. After missing out twice for positions on the Federal District Court, he basically gave up any idea of ever becoming a judge.

Undaunted by his disappointment, Smith decided instead to become an independent practitioner. In the summer of 2003 he left Paul Weiss and set up a private practice. The move turned out to be exactly what he needed: “From the moment I went into private practice, the moment I realized I was doing it, I loved it.” One night in August, only a few months into his new career, Smith got a call from Governor Pataki’s office describing a controversy surrounding the Local Government Assistance Corporation and asking if he would be willing to represent the Governor’s side. Smith claims not to have understood a word about the case, but quickly accepted nonetheless. At first, the case was merely a professional boon for Smith, who had already been pleasantly surprised by the success of his new enterprise. Eventually, however, his skill and hard work would so impress the Governor and his legal department that, in November, Smith became the Governor’s surprise nomination for the New York State Court of Appeals. In less than a year, Smith had gone from believing any judgeship was out of his reach to sitting on one of the most prestigious courts in the country.

In his first three years on the Court, Smith has already developed a reputation for being a smart and independent-minded judge.6 Although he denies having a particular judicial philosophy, his record suggests a tendency for strict construction. In People v. LaValle, where the Court found New York’s death penalty statute in violation of the State Constitution, Smith’s dissent accused the majority of “confus[ing] its own policy preferences with what the due process clause requires.”7 He has also strongly defended private property rights, dissenting from decisions that allowed the state to tax telecommuters8 and take the assets of a charitable organization.9 In the latter case, Smith argued that the organization’s property was private despite being government-supported. As he pointed out, “There may be farmers in this country who have been able to remain in business for years or decades because of government subsidies, but their farms are still their farms, and the government cannot take them without paying just compensation.”10

On the bench, Smith has maintained many of the traits that made him a successful student and lawyer. The attention to detail, needed for effective cross-examinations, now manifests itself in clear and convincing opinions even in the most technical of cases. As a former litigator, Smith is also clearly at his ease during the give-and-take of oral argument. Indeed, he admits that “it took a certain amount of discipline for me to wait until halfway through my first argument before I asked a question.” Leaning forward in his chair and squinting skeptically, Smith challenges a lawyer to defend the least plausible aspects of his argument (“Is it so bad for the jury to know what actually happened?”11 he asked one defense attorney) or tests a position with a series of hypotheticals. Smith’s enjoyment of the law has also not diminished since joining the Court. In Chief Judge Judith Kaye’s words, “What is evident beyond all else is the pleasure [Judge Smith] takes in being here-he relishes it!”12

Smith has also clearly changed his approach in some respects to fit his new role. Often, for example, his opinion will make note of the strength of an opposing view. This technique, which would be a sign of weakness in a lawyer’s brief, demonstrates how carefully he has weighed the issues and makes his final decisions more compelling. In People v. Andrew Goldstein, the Court ordered a new trial for a schizophrenic man convicted of murder on the grounds that a psychiatrist’s recounting of third-party statements at the trial violated his rights under the confrontation clause of the U.S. Constitution. Writing for the majority, Smith openly admitted to being “troubled by the knowledge that another trial will bring added pain to innocent people, particularly to the family of [the victim].”13 Smith’s style of inquiry has also changed since his days as a litigator. Although he often poses challenging questions, he is never merely trying to prove his own point. In fact, he seems most pleased during oral argument when he receives a good answer to a tough question.

Of course, this easy transition from litigator to judge came as no surprise to Smith’s family, who have long benefited from his uncanny ability to transition from litigator to husband and father. Even as a young lawyer at Paul Weiss, Smith often worked straight through until 10:00 at night so that he could then go home and eat dinner with his wife. After his children were born, he dreaded long business trips and was horrified at the thought of “skipping my kids to practice law.” At any family event, he is happiest sitting cross-legged on the floor, where he can debate politics and law while still entertaining his grandchildren. This unstinting devotion to his family will always remain, at least to some, Judge Smith’s most impressive achievement.

Progeny

Judge Smith married Dian Goldston on August 31, 1969. They have three children. Benjamin (born November 4, 1976) is a columnist living in Brooklyn, New York. Emlen (born December 9, 1980) is a graduate student in classics at the University of Pennsylvania. Rosemary (born May 30, 1984), the author of this biography, is a graduate of Williams College and a student at Harvard Law School. On October 5, 2002, Benjamin married Liena Zagare. They have two children, Hugo and Emma.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Published Writings Include:

The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995: A User’s Guide. Publication Date: Summer 1996. Page: 143-179. 24 SECRLJ 143, 1996 WL 458622 (LRI).

Reviewing the ABCs of taking depositions; even top-notch lawyers need a refresher course. Publication Date: July 11, 1994. Page: S3. 7/11/94 N.Y.L.J. S3, col. 1, 1994 WL 403094 (LRI).

SEC adds to compliance officers’ duties. Publication Date: September 6, 1993. Page: 21. 9/6/93 Nat’l L.J. 21, col. 1, 1993 WL 399261 (LRI).

No forum at all or any forum you choose: personal jurisdiction over aliens under antitrust and securities laws. Publication Date: August 1984. Page: 1685-1704. 39 Bus. Law. 1685, 1984 WL 79140 (LRI).

Endnotes

- McKinley, James C. Jr. “Pataki Puts Nonjudge on Court of Appeals.” New York Times 5 Nov. 2003.

- This and all quotations of Robert Smith below from interview by author, 4/22/06, New York, New York.

- Baker, Al. “Lawyer, Not Ideologue.” New York Times 5 Nov. 2003.

- The 42nd Street Development Project, Inc. v. Dream Team Associates, LLC (Index No. 119921/99, August 2, 2002).

- Penry v. Johnson (US Supreme Court, Joint Appendix 531-794).

- Roy, Yancey. “Top Court’s Judge Smith Works Outside the Box.” Rochester Democrat & Chronicle 27 Dec. 2005.

- People v. LaValle, 3 NY3d 88, 141 (2004).

- Matter of Huckaby v. New York State Division of Tax Appeals, 4 NY3d 427 (2005).

- Consumers Union of United States, Inc. v. State, 5 NY3d 327 (2005).

- Ibid, 378.

- Glaberson, William. “In Capital Case, New Judge Signals He Has Open Mind.” New York Times 15 Jan. 2004.

- E-mail correspondence with author, 4/25/06.

- People v. Goldstein, 6 NY3d 119, 132 (2005).