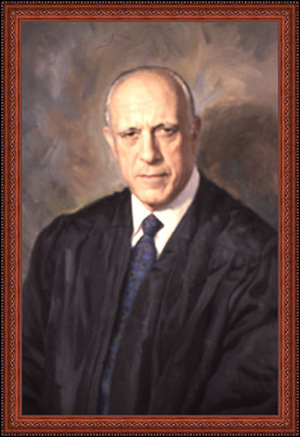

Judge John Scileppi’s long life epitomized the American Dream at its twentieth century best. His parents, Ignazio and Nunzia (née De Meco) Scileppi both came to the United States from Palermo, Sicily in the late 1800s, and married in New York. The Judge to be was born in Corona, Queens on July 17, 1902, the first of their six children.1 He gained early acclaim as a student, an athlete, and as an active member of his church and of several fraternal organizations. John Scileppi began his judicial career at age thirty seven, and, including post Court of Appeals service as a “certificated” Supreme Court Justice, spent 37 more years in robes. When he was elected to the Court of Appeals in 1962, John Scileppi became the first Italian American to sit on the Court in the twentieth century, and only the second (after Charles Rapallo who died in 1887) in the history of the Court.2

The New York City public school system gave young John his fundamental education. At Newton High School in Queens he displayed a variety of talents as a student leader and a star athlete. Elected president of the student body, he gained recognition as a distinguished orator and a skilled debater; he also showed what became a lifelong readiness to put his pleasant baritone voice to song, to the enlivenment of many social gatherings. Topping out at well over six feet tall, John Scileppi demonstrated his athletic prowess on the diamond and on the hardwood. In the early 1920’s he played semi-professional baseball, and, as a member of the Long Island Pros basketball team, played against (among many others) the fabled Boston Celtics.

Reflecting his intellectual vigor, he also undertook studies at Fordham Law School, graduating in 1925 and gaining admission to practice in New York in 1926. Shortly thereafter, John Scileppi had the great good fortune to marry Katherine (Kitty) Shea in 1928. Their marriage spanned 59 years and yielded a bountiful harvest of children (three), grandchildren (eleven), and great-grandchildren (ten).3

The young lawyer ultimately turned to public service, became a Deputy State Attorney General and then Chief Deputy Queens County Clerk (1938). He began his years of service on the bench in 1939 upon election to the Municipal Court, to which he was reelected in 1949. He was soon thereafter elected to the Queens County Court (1951), and when the County Courts were abolished in New York City (1962) became, albeit briefly, a Justice of the Supreme Court.

The history of Judge Scileppi’s electoral successes in Queens County and his progression through the hierarchy of the trial courts mirrored his considerable personal dynamism, shown by his parallel progress to a pre eminent position in the Benevolent Protective Order of Elks, a fraternal affiliation that he valued greatly and served with distinction at the local, state and national levels. Moreover, a staunch Roman Catholic, he participated in the Knights of Columbus, the Holy Name Society, the Bishop Molloy Retreat League, and as a promoter of Queens Elks Retreat Group. And as a proud American born son of Italy he served as president of Italian Charities of America and the Columbian Lawyers Association of Queens County.

In 1962, the Democratic Party and the Liberal Party nominated Judge Scileppi for the position on the Court of Appeals becoming vacant at year’s end upon the retirement of another distinguished Queens native, Hon. Charles W. Froessel (1892-1982). To the surprise of many, Judge Scileppi ran ahead of the Democratic slate and, with Comptroller Arthur Levitt, was one of the two Democratic candidates to win statewide office.4 His tenure on the Court of Appeals began with this admonition from his predecessor:

. . . .John, I wish you well. As I told you when we conferred together, this post will tax you physically and mentally, but it will be both challenging and fascinating. If you derive therefrom but a fraction of the joy of service that I have, you will find it very rewarding indeed.5

One must remember that the time of Judge Scileppi’s ascent to the Court came near the beginning of more than a decade of intense social and political upheaval. In 1962 1963, places like Vietnam, Kent State, and Watergate had no perceivable resonance to the ordinary American; the major battles over Civil Rights and procreative rights loomed on a then distant horizon; Mapp v. Ohio6 was still a novelty to the state court system and Ernesto Miranda was just another anonymous criminal. The Texas School Book Depository and the Lorraine Hotel awaited their infamy. Someone deeply rooted in traditional values of family, faith, and fraternity would indeed face challenges even Judge Froessel’s prescient sentiment could not have envisioned. Within a few months of joining the Court, Judge Scileppi authorized the majority’s opinion ruling that Henry Miller’s novel “Tropic of Cancer” was censorable obscenity.7

Perhaps by background, certainly as a matter of conviction, Judge Scileppi accepted the label “conservative,” at least in the domain of the criminal law. This brand of conservatism embraced the attitude famously expressed by Judge Cardozo in rejecting the imposition of a rule barring illegally obtained evidence: Cardozo was repelled by the notion that “The criminal is to go free because the constable has blundered.”8 This label conservative notwithstanding, Judge Scileppi’s merits as a jurist brought him multiple honors – two degrees honoris causa one from Brooklyn (1969) and the other from New York (1971) Law Schools; installation as a Catholic Knight of Malta (1967), and appointment, while still a member of the Court, as a delegate to the 1967 Constitutional Convention.

Tagging any Judge with any of the facile labels “conservative,” “centrist,” “liberal,” and so on, invites examination to see how well the label fits the reality. Judge Scileppi’s overall approach to the criminal law expressed the view that extension of the protections of defendants’ rights might present unwarranted obstacles to the essential search for truth. That facet of his judicial philosophy aside, his opinion in the case People v. Arthur9 formed a keystone in the protective rules in New York shielding the defendant’s right to counsel far beyond the minimal standards of the Federal Constitution.

As befits a collegial court, specific details of the exchange of views among its members in conference are, and should be, closely cloaked. But however hearty the inevitable clash of ideas, the tenor of warm affection and respect among the Judges of the Court remained constant. Thus, marking the occasion of Judge Scileppi’s departure from the Court (along with Judges Bergan and Gabrielli), Chief Judge Fuld observed:

That we did not always agree on matters that came before the court is not at all surprising, for disagreement is inevitable when seven men of strong will and independent mind, albeit decked out in robes, gather to decide complex and controversial issues. However, such differences, no matter how fervidly or sharply evidenced, could never affect or weaken the precious tradition of this court that its judges shall work together in friendship but that each judge, nevertheless, shall act and speak, shall think and write, freely and independently, with but one end in view to do his share in the all important joint enterprise of administering justice in accordance with law. Only we, your associates, can fully know the close ties and happy relations which have existed among us and the spirit of helpfulness and co operation which has permeated our conferences.10

Upon leaving the Court, Judge Scileppi took advantage of the opportunity to return to the trial bench, and served an additional four years in Supreme Court in Riverhead, Long Island. Finally retiring to the bosom of his family, he quietly lived out an extraordinarily long life, passing away on November 26, 1987, at age 85.11

In memoriam, Chief Judge Wachtler said: “His decade on this court represented a period of drastic social change, during which he held fast to traditional values and contributed specially to the collegial product of this Court’s work.”12

Judge John Scileppi and beloved Kitty now rest in eternal peace in the parish cemetery of St. James Roman Catholic Church in Setauket, Long Island. Requiem Eterna.

Progeny

Judge and Mrs. Scileppi had three children, Kathleen, Barbara, and John. Kathleen married Robert Christman, and they had four children: Kathleen Mary, Jeanne Marie, Robert (Bob), and Steven. Kathleen Mary married Ronald Keenan and they have three children: Ryan, Kevin, and Brendan. Jeanne Marie lives in Manorville and works as an executive in Islandia. Robert (Bob) has a son named John (Jack) and works in Manhattan. Steve is married to Elizabeth Schuette and they both work in Manhattan.

Barbara married Paul Nuget and they had three children: David, Anne, and Paul (PJ). David married Jeanine De Franca and they live in Southampton, NY, with their two children: Reece and Hudson. Anne also lives in Southampton, NY. Paul lives in Florida and has a daughter named Emma.

John Scileppi has four children: Jennifer, Laura, Alison, and John (Jake). Jennifer married David Grebe, and they have two children: Carolyn and Henry. Laura is the manager of an elite children’s shop in Boston. Alison married Rob Sprague and they live in Stowe, VT, and have a daughter, Olivia.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

In addition to the material cited in the endnotes, most of the information concerning Judge Scileppi is of anecdotal origin. Thus this author is indebted to Mr. David Nugent, Judge Scileppi’s grandson, and Vincent F. Nicolosi, Esq., the Judge’s nephew (son of Mary, the Judge’s sister).

The brief glimpse at the relationship between the Judge and his law clerks draws on personal experience and conversations with others who enjoyed the honor and pleasure of serving the judge and the Court.

Published Writings Include:

Scileppi, Obscenity and the Law, 10 NY Law Forum 297 (1964).

Endnotes

- The others were Louis, Frances, Samuel, Mary, and Michael.

- Proceedings on the Death of Hon. Charles A. Rapallo, 107 NY 685, 691 (1887).

- See “Progeny” section of this Biography.

- Hunt, Scileppi Elected to Appeals Court, NY Times, Nov. 18, 1962, at 27.

- Remarks on Retirement of Judge Froessel, 12 NY2d vii, 1x (1962)

- 367 US 643 (1961).

- People v. Fritch, 13 NY2d 119 (1963).

- People v. Defore, 242 NY 13, 21 (1926).

- 22 NY2d 325 (1968).

- Remarks on Retirement of Judges Scileppi, Beyan and Gibson, 31 NY2d vii, viii.

- New York Times, Nov. 28, 1987, obituary.

- In Reference to the Death of Hon. John F. Scileppi, 70 NY2d vii. The young lawyers who served on the Judge’s staff as his law clerks have all expressed their admiration for the judge’s open mindedness. His standard admonition when welcoming each new clerk to chambers was that he had no use for “yes” men. All his former clerks carry feelings of fond filial admiration and respect.