“In a State that has given America many of its greatest jurists, none stood higher than Irving Lehman, Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals.”1 So wrote the New York Times in its editorial eulogy shortly after Lehman’s death. The scion of a powerful merchant banking family, he served as a judge from 1908 to 1944. Over those 36 years – stretching from the Horse and Buggy era to the dawn of the Nuclear Age – he decided thousands of cases. He wrote opinions and extra judicial articles that placed him in the vanguard of judicial thought. He was ahead of his time in arguing that courts should shape the common law pragmatically, protect civil liberties aggressively, and defer to the executive and legislative branches when acting to ameliorate social and economic ills. He also left an enduring legacy off the bench through his work on behalf of numerous civil, philanthropic, and religious causes. While much of this remarkable career has been forsaken by history, the fact remains that “the judicial system of the country had no more conscientious officer” than Irving Lehman.2

Lehman’s Childhood

Lehman was born in New York City on January 28, 1876.3 His father, Mayer Lehman, and mother, Babette Newgass Lehman, immigrated to the United States from Bavaria in 1848.4 They settled in Montgomery, Alabama, where Mayer joined his brothers, Henry and Emanuel, and established one of the largest cotton broker firms in the state.5

After the Civil War, Mayer Lehman moved to New York City and established the counterpart of the Montgomery business.6 He helped organize the New York Cotton Exchange, becoming a charter member of its Board of Directors.7 Over time Mayer and Emanuel (Henry passed away in 1856) expanded their business to other commodities, like coffee and oil, and then moved into underwriting and investment banking. They called their firm Lehman Brothers and by the turn of the century it was one of the most important investment banking houses in the country.8

Irving Lehman was the next to youngest of Mayer and Babette’s seven surviving children.9 The family lived in the privileged and inbred world of German Jews in New York City.10 The Lehman household was warm hearted and cultivated, and the children were instilled with a sense of responsibility and purpose.11

Irving was particularly close with his younger brother, Herbert, who grew up to become a New York Governor and United States Senator. As boys, they were inseparable.12 Their relationship reached its heights in adulthood when Irving, as Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, administered the oath of office to Herbert as Lieutenant Governor on two occasions and as Governor on four occasions.13

Irving Lehman’s childhood was not without challenge. Most notably, from an early age he was almost completely deaf. Self conscious of this condition, which others joked about behind his back, he tended to avoid an active social life.14 Nevertheless, his physical disability did not stand in the way of his later pursuit of a career in public life.

Preparatory, College and Law School Education

Lehman prepared for college at the then famous Sachs Collegiate Institute School of Boys. The headmaster, Dr. Julius Sachs, was a renowned educator. He imposed a demanding regimen on the students, who were required to come to classes dressed in suits and starched collars.15

“Reflective and studious, Irving seemed marked out from childhood for a learned career in the law.”16 He showed a strong interest in legal history, followed newspaper accounts of important cases, and often talked with attorneys who were family friends.17 One such person was Edward Douglass White, who later became Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.18

In 1892, Lehman entered Columbia College, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1896 and a master’s degree in political science the following year.19 Joseph M. Proskauer, a college classmate of Lehman, recalled that he “had none of the adolescent brilliance which too often warps the quest for knowledge; but rather an innate modesty which prompted him to days and nights of toil to glean the learning and train the mind for the tasks that lay ahead.”20

Lehman graduated from Columbia Law School in 1898 with an LL.B., winning the Toppan Prize for excellence in constitutional law.21 Honorary degrees followed in later years, including Doctor of Law from Columbia College in 1927, St. Lawrence University in 1936, and Syracuse University in 1943; and Doctor of Hebrew Literature from the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1936.22

Early Career as a Practicing Attorney and Election to the Supreme Court

Unlike his brothers, Irving Lehman did not enter the family business.23 Instead, he practiced law in New York City with the firm of Marshall, Moran, Williams & McVicker, where he made partner in 1901. He devoted most of his practice to commercial law and was recognized as one of the bar’s rising stars.24

At age 25, Lehman married Sissie Straus, the only daughter of merchandising magnate and philanthropist, Nathan Straus.25 The marriage was an unusually happy one.26 “They were wrapped up in one another with a love, a devotion, and a companionship that constantly grew with the years.”27 Sissie Lehman was well educated, highly accomplished, and possessed a forceful and assertive personality.28 She took a keen interest in her husband’s career and helped him realize his full potential as a lawyer and judge.29

In 1906, Lehman became a named partner in the firm of Worcester, Williams & Lehman.30 Even at this early point in his career, he saw the law as a higher calling crucial to the nation’s well being a view he expressed to the students of Brooklyn Law School in 1907:

A lawyer is one who uses his knowledge of the law to serve justice and not to thwart it; to maintain the law, not to evade or undermine it. In countless offices scattered throughout the country, lawyers at this very minute are guiding and protecting men, women and children who have sought their help. The trickster . . . , the ambulance chaser and the counselor of those who seek to prey upon society, loom large in the public eye. They are more dramatic in their destructive activities than the lawyers and judges who day in and day out build and preserve the common law and the institutions of America; who lead its public opinion and guide in large part its affairs. It is upon them that America must rely for the wise solution of many of its perplexing problems.31

A life long Democrat, Lehman was elected to the New York State Supreme Court, First Judicial District, in 1908, the result of a compromise between two factions in New York City’s Democratic organization.32 He was 32, making him one of the youngest men in the history of the State to become a Supreme Court Justice.33 On grounds of merit the selection was unassailable – in fact, it was widely approved by the media and the bar.34 But years later Lehman acknowledged that family connections played a role in his ascension to the bench:

I was a very young lawyer, in practice only a short time; I was deaf; and I was Jewish. None of these helped. But I was married to Nathan Straus’s daughter, and Mr. Straus was a dear friend of Al Smith, and Smith knew the governor of New York. So I became a judge.35

Lehman soon acquired a reputation as an industrious trial justice, with powerful analytical faculties and common sense. Of his first years on the bench, a fellow judge recalled that Lehman:

had a power of cool, analytical judgment. Thorough, shrewdly conversant with the ways of the world, his instinct for the significant and essential always present, he could seize the point at issue, skillfully disentangle the twisted strands of the evidence, bring out of a crushing mass of facts, and arrive at a dispassionate, reasoned judgment.36

In 1922, at the expiration of his first fourteen year term, Lehman was re elected to Supreme Court on the nomination of both the Democratic and Republican parties.37

Election to the Court of Appeals

A year after Lehman’s reelection, in which much of his work had been at the Appellate Term, both major parties nominated him to be an Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals.38 He was elected and began his service on the Court on January 1, 1924. He was 48 years old.

His long experience as a trial justice in a busy metropolitan court stood him in good stead. He was joining a bench on which sat such seasoned and independent jurists as Chief Judge Frank H. Hiscock, three future Chief Judges, Benjamin N. Cardozo, Cuthbert W. Pound and Frederick E. Crane, and Associate Judges William S. Andrews and Chester B. McLaughlin. With over 140 years of judicial experience between them, this extraordinary group of jurists constituted the finest common law tribunal of last resort in the nation.39

Lehman especially enjoyed the company and intellectual rivalry of Benjamin Cardozo, who later became an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. They had long been friends and shared much in common.40 Both were graduates of Columbia Law School, loved books, and were golfing companions, spending as much time talking as playing.41 After Lehman joined the Court, their relationship grew into a brotherly bond.42 Cardozo was treated as part of the Lehman family, often dining and vacationing with them.43 The friendship found its culmination when Cardozo chose to spend his final days and died in 1938 at the Lehmans’ estate in Port Chester, New York.44

Although not wont to express his personal feelings in public, Lehman acknowledged the depth of his affection and intellectual debt to Cardozo after his death:

I had the privilege of close association with him in the work of the Court of Appeals and at home. I loved him, but so did all who knew him well. I realized that, in truth he was the Master who was bringing new methods and new ideas into judicial decisions. I felt the influence of his great soul and mind.45

Qualities as a Judge

Lehman had a prodigious capacity for work, of which his published opinions represented but a fraction of his efforts.46 He was renowned for his knowledge of the minute details of every case, regardless of whether it was assigned to him for report or to another judge.47 During the Court’s recesses he would twice read every report and draft opinion he received.48 The salutary impact on the Court’s work of Lehman’s meticulous study of the facts left a strong impression on William J. Armstrong, the Clerk of the Court from 1924 to 1936:

[O]f all the judges who ever sat in this Court while I have been here, none has been more useful than Irving Lehman. . . . I do not mean that necessarily he was the most learned or the most brilliant, but I do mean he always knew his facts and always came to a happy practical conclusion that set the court on the right path.49

Lehman’s colleagues respected his objectivity and ability to quickly grasp the nettle of a case. Frederick E. Crane, who served with Lehman on the Court for 16 years, remarked: “I never knew a man who excelled Judge Lehman in laying aside all his natural feelings and inclination, prejudices or beliefs in order to judge impartially and fairly the cause before him.”50 As for his ability to cut straight to the heart of a complex legal problem, Cuthbert Pound said: “Lehman can take the hide off a case faster than any man I have ever known.”51

Once Lehman made up his mind about a case, he was a tenacious advocate for his position when the Court met in conference. Edmund H. Lewis, who succeeded Lehman as Chief Judge, recalled that “when Irving Lehman was presenting the view of a dissenter, his contribution to the debate, while always fairly and powerfully presented, was rarely a cooling draft.”52 Similarly, Charles H. Desmond, another future Chief Judge, remembered that Lehman sometimes got “quite excited” during the conferences.53 Even with Cardozo, Lehman would fight to get a majority of the Court. “When they disagreed in their vote in a case, each of them put his whole effort into capturing the votes of his associates so that he would have a majority.”54

The force of Lehman’s advocacy was magnified by his distinctive appearance and bearing:

A tall sturdy figure, he had a natural dignity in which pompousness found no place. Underneath his sphinx like calm there was deep feeling. His face was at once strong and sensitive, with gentle, querying, brown eyes, quietly intent and at times a brooding sadness in them. In conversation his face was mobile, with an attractive smile; in repose it assumed a thoughtful, rather stern expression. Unaffected and forthright, he was austere at times, but often he was radiantly responsive to those about him. To meet him was to feel yourself in the presence of a strong and unusual personality.55

Another notable aspect of his appearance was the presence of a hearing aid, without which he would not have been able to do his job.56 Indeed, Lehman may be the only judge in Court of Appeal’s history who had a life long physical disability that required accommodation. He installed at Court of Appeals Hall three cumbersome hearing aid devices, each consisting of a large metal box amplifier on the floor, a large box microphone on the desk, and an ear attachment which plugged into the microphone. One of these large sets remained at his place on the bench, one at his place at the conference table and one on his desk in his chambers. In traveling between these spots he also had a smaller portable set. 57

Judicial Outlook

In 1936, upon the expiration of his first term on the Court, Lehman was re elected as an Associate Judge, having been nominated by the Democratic, Republican, and American Labor parties.58 By this point he had an acknowledged place as one of the nation’s most eminent jurists.59 Influential commentators like Jerome Frank, in his seminal book Law and the Modern Mind (1930), placed Lehman in the upper echelon of American jurists along with Cardozo and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.60 So, too, when Cardozo’s death in 1938 created a vacancy on the United States Supreme Court, many believed that Lehman should and would fill it.61

Lehman’s judicial outlook evolved considerably from the time he first became a trial justice.62 By his own admission, his initial understanding of the judicial process was naïve.63 He viewed the judicial function as requiring little more than the rigid application of known rules of law, which were fixed or discovered, to the facts of the case at hand. It did not take long, however, before he recognized that the law was a living, vital force that must serve the needs of society.64

Lehman espoused a common law jurisprudence, the predominant characteristics of which were pragmatic. Facts, realities, and consequences were of paramount importance. The law must be functional. Its rules, administration and judicial process should justify themselves by the stern test of workability. Of course, he was guided by precedent, which provided continuity and was the foundation of a stable legal order.65 But precedent needed to be examined to determine if it was in harmony with the needs of an “everchanging society, and not perpetually restricted to the exact interpretation placed upon it when first enunciated.”66 The art of judging, therefore, was striking the proper balance “between the will to do justice in the individual case and the duty of preserving . . . certainty and uniformity which are essential parts of . . . the law” too.67

In a law review article entitled the “The Influence of the Universities on Judicial Decision,” which was published in 1924, Lehman articulated his vision of the judicial function:

The judge has the task of using forms and procedure, statutes and precedents – the law, in all its phases, which he has been called upon to administer – as an instrument with which to do justice between man and man; but he has also the responsibility of preserving and even molding the law so that human relations can be fitly ordered by it in the future.68

This pragmatic viewpoint, while unremarkable today, was widely regarded in the 1920s as “a legal version of hard core pornography.”69 Lehman braved potential criticism and helped lay the ground work for a jurisprudential revolution – the so called legal realist movement – which continues to influence law schools and courts.70

In the public and constitutional law realm, Lehman’s jurisprudence varied depending on the character of the interest acted upon by the government. When the legislative and executive branches sought to ameliorate social and economic conditions, his inclination was to defer to their efforts.71 He had a healthy democratic respect for the values of society and the roles of other governmental entities. He was not a populist – on the contrary, he considered himself part of an enlightened elite. But he strongly believed in the presumptive legitimacy of legislative and executive action, which represented an extension of the public will.72 This view – which would later become a commonplace of constitutional law – was then struggling for acceptance.73 It placed Lehman at odds with the conservative bloc of justices on the United States Supreme Court that “openly resisted the legislative reforms of the New Deal and thereby helped precipitate the Court packing crisis in 1937.”74

“Lehman was similarly in advance of his times on civil liberties issues.”75 A self described libertarian, he believed that constitutional freedoms were inalienable and God given,76 and called for increased judicial intervention when government infringed upon them.77 This outlook found its most notable expression in his concurring opinion in People v. Sandstrom,78 where he defended the refusal by children of Jehovah’s Witnesses to salute the flag in school on pain of expulsion. This case was decided shortly before Justice Felix Frankfurter, for a majority of the United States Supreme Court in 1940, ruled that a local school board in Pennsylvania could impose on children a compulsory flag salute, regardless of their religious beliefs.79 But a few years later, during the throes of World War II, the Supreme Court saw things Lehman’s way, striking down as unconstitutional a West Virginia flag salute statute.80

Lehman’s libertarian instinct can also be seen in cases involving the rights of the accused. He was especially critical about police utilizing unsavory means to extract confessions from criminal suspects.81 In People v. Doran,82 for example, he dissented from the majority’s ruling that a confession was voluntarily given. The defendant’s confession was allegedly prompted by a policeman who conducted an all night interrogation while wearing a boxing glove. Lehman rejected these tactics:

The courts should not hamper the police by technical rules nor reverse a just conviction because of technical error, but the courts cannot sanction disregard of the substantial rights of an accused . . . . The courts may not approve the punishment even of the guilty, if guilt is established, by means which are destructive of the fundamental rights of the accused. We have long ago abolished the rack and thumbscrew as a means of extorting confession; the courts cannot sanction the introduction of the boxing glove in their place.83

Election as Chief Judge

As 1939 was drawing to a close, so too was the tenure of Chief Judge Frederick E. Crane, who at the end of the year was compelled to retire because of the constitutional age limit of 70. Lehman, the Senior Associate Judge on the Court, was Crane’s logical successor. The established practice then was for the Democratic and Republican leaders to nominate jointly the senior judge for head of the Court.84

In some quarters, however, Lehman’s elevation to the Chief Judgeship was controversial. His brother was then Governor of the State. Never before in New York had brothers simultaneously headed the executive and judicial branches. Some saw it as a conflict of interest and a concentration of too much power in a single family.85 Irving and Herbert’s close relationship was no secret. Irving’s wife occasionally served as hostess at the Executive Mansion in Albany for her brother in law Herbert during his terms as Governor when his own wife was absent.86 Less well known, perhaps, was that Irving acted as a confidant to Herbert throughout his political life.87

The “brother issue” was raised most prominently by Fiorello H. LaGuardia, the Mayor of New York City. LaGuardia was an outspoken critic of the Court of Appeals, whose judges he complained were old and out of touch with New York City’s problems.88 LaGuardia let it be known that he was considering running for Chief Judge as a Republican or Independent. He also played upon the fears of upstate Republicans that Herbert would make a partisan appointment to fill the vacancy created by Irving’s elevation to the Chief Judgeship.89

But LaGuardia’s trial balloon soon burst. The media and organized bar overwhelmingly threw its weight behind Lehman.90 “Of Judge Lehman’s eminent qualifications it is almost impertinent to speak,” the New York Times observed.91 Likewise, the New York State Bar Association and the Association of the Bar of the City of New York endorsed Lehman’s appointment, and the nominations of the Democratic, American Labor, and Republican parties followed in rapid order.92

At the same time, LaGuardia’s advisors urged him not to run for a position that his volcanic personality made him unfit to hold.93 Thomas D. Thacher, who himself later became a Judge of the Court of Appeals, told LaGuardia that the brother issue could fan the fires of anti Semitism.94 LaGuardia abhorred religious intolerance and was persuaded to withdraw his name from consideration, clearing the way for Lehman’s election in 1939.95 He was sworn in on the last day of the year after a series of congratulatory dinners.96

In the tradition of his predecessors, Lehman was a strong Chief Judge. “A man of immense dignity, [he] enforced strict decorum during oral argument.”97 Some learned this the hard way like Nathaniel L. Goldstein, New York’s Attorney General from 1943 to 1954. In the first and last case that he personally argued before Lehman as the Court’s presiding officer, Goldstein began his oral argument with what amounted to a political harangue. But Lehman halted him: “Sir, do you have a legal argument? If not, I suggest that you leave that to the Solicitor General, and SIT DOWN.”98

Priviate Life and Philanthropic Work

Lehman lived at the pinnacle of American life. His brother was New York’s Governor. His best friend was Benjamin Cardozo.99 Albert Einstein was his houseguest not long after the world renowned physicist fled to the United States from Nazi Germany.100 He knew well the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, whom he had twice sworn in as Governor of New York.101

By all accounts, Lehman was a happy person with a wide range of interests.102 Although he and his wife were childless, they were extremely close with their relatives and enjoyed spending time with them.103 Devoutly religious,104 he became a self taught scholar in ancient and modern Hebrew culture.105 He was also passionate about books and art.106 He spent years amassing a world class collection of Judaica, listing each acquisition in a small notebook in which he set down details relating to the objects.107

The great wealth Lehman inherited allowed him to enjoy a privileged lifestyle.108 But he gave back an enormous amount of his time and money to civic, philanthropic, and religious causes. In his college days he became a volunteer social worker at Lillian Wald’s Henry Street Settlement.109 Later, he served on the Executive Committee of the Boy Scouts Foundation of Greater New York and in 1916 established “Camp Lehman,” a summer camp for underprivileged boys on his Port Chester estate.110 He worked to achieve racial and religious harmony, collaborating with the Mayor of the City New York to improve inter racial relations and serving on organizations that combated prejudice such as the Goodwill Union and the Committee on Better Understanding.111

But by far and away the lion’s share of Lehman’s time off the bench was devoted to Jewish communal and philanthropic activities. Here he made an indelible mark, becoming one of the foremost leaders of American Jewry.112 He was active in the 1920’s helping the American Jewish Committee combat Henry Ford’s anti Semitic propaganda.113 From 1929 to 1938, he was President of Congregation Emanu El, one of the most important Reform synagogues in the nation.114 He was a founder of the National Jewish Welfare Board and served on its board from 1917 to 1940. During World War I he was a member of the Jewish Welfare Board’s Executive Committee and Chairman of the Committee on Religious Activity, which distributed prayer books for use among Jewish soldiers. As President from 1921 to 1940, he developed the plan for the Jewish Welfare Board to become the national coordinator of Jewish community center work.115

He was a member and officer of the American Jewish Committee for three decades, becoming an Honorary Vice President in 1942. For eight years he was President of the 92nd Street YMHA.116 He was Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Intercollegiate Menorah Association and the Admissions Committee of the Federation for the Support of Jewish Philanthropic Agencies. From 1901 to his death he served on the Board of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, and was elected its Honorary Secretary. He was also a member of the Executive Committee of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations; the Board of Governors of the American Friends of the Hebrew University in Palestine; and the Visiting Committee for the Semitic Museum at Harvard University.117

Final Years

During the last years of Lehman’s life his prominence in the public’s mind grew to a stature known by few other state court jurists.118 In 1939, he was asked to deliver an address on the Central Park Mall before 20,000 people who gathered for a citizenship rally.119 Later that year, he delivered an address on “Youth and Civic Responsibility” broadcast over the radio by the National Broadcast Company.120

On May 28, 1941, Lehman presided over a ceremony commemorating the 250th anniversary of the Founding of the New York State Supreme Court.121 These exercises, in which President Roosevelt and Governor Lehman participated, were held in the chamber of the New York State Assembly in Albany.122 Irving’s and Herbert’s nephew, Arthur Lehman Goodhart, a distinguished Professor of Jurisprudence at Oxford University, traveled from England to participate as a speaker too.123

However, Lehman’s last years were saddened by the events of World War II. He was devastated by the destruction of European Jewry during the Holocaust.124 Also, Herbert’s son, Peter, a decorated war hero, was killed during a mission against Germany on March 31, 1944.125 Many of Irving’s public speeches during this period have an elegiac quality, frequently alluding to the war and religious faith.

Probably the summit of Lehman’s career in the public consciousness occurred on the evening of June 19, 1945, when the City of New York held an official welcoming dinner at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in honor of General Dwight D. Eisenhower on his triumphal home coming as the leader of the Allied Forces. The dinner followed a ticker tape parade for Eisenhower witnessed by an estimated 4,000,000 people. Approximately 1,600 people attended the dinner, at which Lehman was selected to give the welcoming address on behalf of the City.126

“Because the heart of New York was in that welcome and because . . . Lehman sensed so deeply, and with such accurate knowledge of the facts, what an allied victory had meant to all peoples of the earth, he felt himself greatly honored when he was chosen to introduce the City’s guest.”127 The speech he delivered expressed a singular love of America as the land of opportunity for people of all religious faiths and ethnic groups.128

Lehman’s welcoming address proved to be his valedictory. Three weeks after delivering it, as he walked around his Port Chester estate with his pet dog, Carlo, he collided with the dog and broke his left ankle. Confined to a wheel chair, he hoped to be able to return to work for the opening of the Court’s October session. But an embolism developed, his heart began to fail, and on September 22, 1945 he died before his colleagues on the Court even knew he was ill.129 He was buried in Salem Fields Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.130

Memorial exercises were held at Court of Appeals Hall on October 23, 1945. Judge Charles B. Sears, Joseph M. Proskauer, and Attorney General Nathaniel L. Goldstein spoke for the bar and Chief Judge John T. Loughran responded for the Court of Appeals.131

On November 25, 1945, over 1,100 people attended a public memorial service held for Lehman at Congregation Emanu El in New York City.132 Numerous luminaries of the bench, bar, and Jewish community addressed the gathering. But the most eloquent words were perhaps spoken by Lehman’s Rabbi, Dr. Samuel H. Goldenson:

[Lehman] belonged to that rare company of men who are endowed with a goodly measure of the qualities attributed by the Prophet Isaiah to that moral and spiritual personality, who, in the course of time is to lead mankind to the ultimate goal of peace. . . . [A] God conscious and reverend person, his life and labors rested upon knowledge and love of the moral law.133

Progeny

Lehman and his wife left no offspring.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Birge, Address Commemorating The 100th Anniversary of Irving Lehman Graduation from Columbia Law School (Oct. 8, 1998).

Crane, Address Before The Association of the Bar of the City of New York (Oct. 16, 1945), in Assoc. of the Bar of the City of N.Y., Year Book, 1946 at 406.

Goldstein, in Proceedings in the Court of Appeals in Reference to the Death of Honorable Irving Lehman, N.Y. Reports, vol. 294, at xi.

Lewis, The Contribution of Judge Irving Lehman to the Development of the Law (1951).

Loughran, in Proceedings in the Court of Appeals in Reference to the Death of Honorable Irving Lehman, N.Y. Reports, vol. 294, at xiii.

McKenna, 12 American National Biography Encyclopedia 437 (1999).

Proskauer, in Proceedings in the Court of Appeals in Reference to the Death of Honorable Irving Lehman, N.Y. Reports, vol. 294, at vii.

Proskauer, Memorial of Irving Lehman (Oct. 16, 1945), in Assoc. of the Bar of the City of N.Y., Year Book, 1946 at 403.

Rosenman, Irving Lehman, 6 The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia 595 (1948).

Roosevelt, My Day, Sept. 24, 1945.

Sears, in Proceedings in the Court of Appeals in Reference to the Death of Honorable Irving Lehman, N.Y. Reports, vol. 294, at ix.

Shientag, Chief Judge Irving Lehman, Citizen and Jurist: An Appreciation, XXXV Menorah Journal 155 (Spring 1947).

Schneiderman, Irving Lehman, 1876 1945, 48 Am. Jewish Y.B. 85 (1947).

Weil, A Tribute to Judge Irving Lehman (Sept. 29, 1945).

Wiecek, The Encyclopedia of New York State 881 (2005).

Wiecek, Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement Three, 1941 1945, at 451.

Wiecek, The Place of Chief Judge Irving Lehman in AmericanConstitutional Development, 60 Am. Jewish Hist. Q. 280 (1971).

Published Writings

An Address Welcoming General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1945).

The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, 57 Harv. L. Rev. 1240 (1944) (book review).

The Moral Foundation of Law, An Address Delivered at Temple Emanu El in New York City (Nov. 12, 1944).

Address Delivered at the Sixty Sixth Annual Meeting of the New York State Bar Association (Jan. 22, 1943), in LXVI Ann. Rep. of the N.Y. St. B.A. 457 (1943).

The Supremacy of the Law, An Address Delivered at the Annual Meeting of the New York State Bar Association (Jan. 24, 1941).

The Influence of Judge Cardozo on the Common Law (1942). This lecture, which was given on Oct. 8, 1941 before the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, was also published in: 1 Benjamin N. Cardozo Memorial Lectures Delivered Before the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, 1941 1995, at 15 (1995); and 35 Law. Libr. J. 2.

Frederick Evan Crane, 9 Brooklyn L. Rev. 113 (1940).

An Address by Irving Lehman Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, in The Supreme Court of the State of New York _ 1691 1941 _ Exercises Upon the Occasion of the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of Its Founding 33 (1941).

Judge Cardozo in the Court of Appeals, 52 Harv. L. Rev. 364 (1939). This is one of the “Essays Dedicated to Mr. Justice Cardozo” (1939), which were originally published in volume 39 of the Columbia Law Review, volume 52 of the Harvard Law Review, and volume 48 of the Yale Law Journal.

Benjamin Nathan Cardozo: A Memorial (1938).

Remarks Before the Bar and Officers of the Supreme Court of the United States at the Exercises Held in Memory of Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo (Nov. 26, 1938), in 1 Memorial of the Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States 431 (1981). These remarks were also published at XXVII Menorah Journal 171 (Spring 1939).

The Constitution: The Safeguard of Our Religious Liberties, An Address Delivered Before an Assembly at the Jewish Theological Seminary (Dec. 16, 1937).

Foreward to Max James Kohler, Immigration and Aliens in the United States: Studies of American Immigration Laws and the Legal Status of Aliens in the United States at iii (1936).

Max J. Kohler, 37 Am. Jewish Y.B. 21 (1935).

Address Before the Joint Conference on Legal Education in the State of New York (June 28, 1935).

Address at the 25th Anniversary of American Jewish Committee, in 34 Am. Jewish Y.B. 335 (1932).

The One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Constitutional Establishment of Religious Liberty, An Address Before the Judaeans (April 24, 1927), in Luigi Luzzati, God in Freedom: Studies on the Relations Between Church and State at 661 (1930).

Memorial Address for Louis Marshall (Nov. 10, 1929), in Louis Marshall: A Biographical Sketch and Memorial Addresses 89 (1931).

Constitutional Liberty, in Christian and Jews: A Symposium for Better Understanding at 331 (1929).

Address Before the N.Y. County Lawyers’ Association, in 1928 N.Y. County Law Ass’n Y.B. 295 (1928).

The Commonwealth Committee’s Report on The Law of Evidence, 27 Colum L. Rev. 890 (1927) (book review).

Religious Freedom as a Legal Right, Am. Hebrew, Sept. 23, 1927, at 602.

Technical Rules of Evidence, 26 Colum. L. Rev. 509 (1926). This article was also published at 4 Tenn. L. Rev. 125 (1926).

The Influence of the Universities on Judicial Decision, 10 Cornell L.Q. 1 (1924).

Additional Research

Irving Lehman’s widow, Sissie Lehman, destroyed all of his papers in her possession at the time of his death, including his correspondence with Benjamin Cardozo. But some of Lehman’s correspondence and other papers survive in The Hebert H. Lehman Suite and Papers at Columbia University; in the archives of the Jewish Welfare Board at the American Jewish Historical Society (15 West 16th Street in New York City); and amongst the papers of his nephew, Arthur Lehman Goodhart, at the University of Oxford, Bodleian Library.

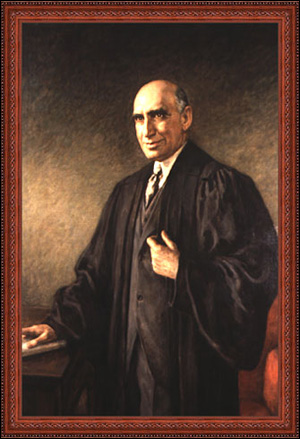

Oil portraits of Lehman hang at Court of Appeals Hall in Albany, New York, and at Congregation Emanu El, in New York City. There is also a bronze bas relief portrait of Lehman at the Friedenberg Collection, Jewish Museum, in New York City.

Endnotes

- Judge Irving Lehman, N.Y. Times, Sept 24, 1945, at 18.

- Marian C. McKenna, 12 American National Biography Encyclopedia 437, 437 (1999); see also William M. Wiecek, The Place of Chief Judge Irving Lehman in American Constitutional Development, 60 American Jewish Historical Quarterly 280, 303 (1971) (Lehman’s successor as Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, Edmund H. Lewis, called Lehman “one of the few truly great judicial officers of [his] time”).

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 281; Bernard L. Shientag, Chief Judge Irving Lehman, Citizen and Jurist: An Appreciation, XXXV Menorah Journal 155, 156 (1947).

- Id.; Allan Nevins, Herbert H. Lehman and His Era 4 7 (1963).

- Id.

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 12 13.

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 156.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 281 82.

- Id. at 281. Mayer and Babette Lehman had four boys (Sigmund, Arthur, Irving, and Herbert) and three girls (Hattie, Lissette, and Clara). Nevins, supra note 4, at 3, 8, 13, 35.

- See Stephen Birmingham, “Our Crowd”: The Great Jewish Families of New York 47, 69 70, 76 78, 253, 329 (1967); Wiecek, supra note 2, at 281; Nevins, supra note 4, at 22 23; Harry Schneiderman, Irving Lehman, 1876 1945, 48 The American Jewish Y.B. 5707 (1946 47) 85, 85 86 (1948).

- Arthur Schlesinger, Herbert H. Lehman: the Conservative as Radical 4 (1967); Nevins, supra note 4, at 18 29.

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 15.

- Letter from Herbert Lehman to Louis Nizer, Oct. 22, 1947.

- See Wiecek, supra note 2, at 286 (“During his years as a trial judge on the Supreme Court, it was a standing joke with the bar that objections to his rulings would be ‘overheard’ instead of ‘overruled.'”).

- Id. at 282; Nevins, supra note 4, at 3, 15, 27 28; Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 86.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 282; Nevins, supra note 4, at 15, 17.

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 17.

- Id. at 17, 20 21.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 282.

- Comments of Joseph M. Proskauer at Memorial Proceedings for Chief Judge Lehman, in 294 N.Y. at vii.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 282; Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 86.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 282; Shientag, supra note 3, at 156.

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 156.

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 45; Shientag, supra note 3, at 156.

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 156.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 282; Shientag, supra note, 3, at 156.

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 156.

- Wiecek, supra note 2 at 282 83.

- Id. at 283 (“Sissie took a great interest in her husband’s work, reading many of the briefs of cases coming before him and personally attending the arguments of those cases that interested her.”), 285 n.13 (noting Sissie Lehman’s efforts to secure for her husband an Appellate Division appointment).

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 45.

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 160 (quoting Lehman). This speech appears to be the first public record of Lehman’s deeply felt commitment to improving the standards of the bar and of legal education. To this end, he later served as a member of the Board of Visitors of Columbia Law School and the Joint Conference on Legal Education and Chair of the Judicial Conference on Legal Education. Id. at 159; Wiecek, supra note 2, at 284; Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 88 89.

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 156 57.

- Id. at 157.

- Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 87.

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 46.

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 157.

- Id.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 285. Lehman’s recognized abilities played a role in securing the nomination, as did his formidable family connections. In his memoirs, the Bronx Democratic political leader, Ed Flynn, recalled that Lehman’s nomination was agreed upon during a meeting between Flynn and the head of Tammany Hall, Charles F. Murphy. The story goes that, while Flynn and Murphy were discussing a vacancy on the Court, Lehman’s parents in law, Mr. and Mrs. Nathan Strauss, came to them and said: “Mr. Murphy, you are going to make my boy [i.e., Irving Lehman] the judge of the Court of Appeals, aren’t you?” Murphy told Flynn: “How could anyone refuse that sweet old couple?” and signed off on Lehman’s nomination for the vacancy. Id. (citing Edward J. Flynn, You’re the Boss 115 16 [1947]).

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 285 (“The court on which Lehman took his seat in 1924 has been called by high authority ‘the second most distinguished judicial tribunal in the land’ ceding pride of place only to the Supreme Court of the United States.”).

- George S. Hellman, Benjamin N. Cardozo: American Judge 119 (1969).

- Andrew L. Kaufman, Cardozo 149 (1998).

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 153.

- Id. at 131, 195, 485 86; see also Letter from Raymond J. Cannon to William M. Wiecek, February 23, 1970, at 3 (“Judge Cardozo was a very frequent guest at the Lehman homes during his continuance [in Albany while on the Court of Appeals] as well as after he went to Washington . . . . We are told . . . that Judge Cardozo found great happiness and warmth with the Lehmans and that he enjoyed this closeness completely.”).

- Kaufman, supra note 41, 131, 567; Hellman, supra note 40, at 119.

- Irving Lehman, Benjamin Nathan Cardozo: A Memorial 8 (1938).

- Lehman’s writings appear in the Court of Appeals Reports in Volumes 237 to 294. All together he penned 734 opinions of which 609 expressed the view of a majority of the Court, 24 were concurring opinions and 101 were dissents. Edmund H. Lewis, The Contribution of Judge Irving Lehman to the Development of the Law 7 8, 11 (1951).

- Comments of John T. Loughran at Memorial Proceedings for Chief Judge Lehman, in 294 N.Y. at xi; Comments of John Sears at Memorial Proceedings for Chief Judge Lehman, in 294 N.Y. at xi; Shientag, supra note 3, at 173.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 287.

- Comments of Joseph M. Proskauer at Memorial Proceedings for Chief Judge Lehman, in 294 N.Y. at viii (quoting William Armstrong).

- Frederick E. Crane, Address Before The Association of the Bar of the City of New York (Oct. 16, 1945), in 1946 Assoc. of the Bar of the City of N.Y. Y.B., at 407.

- Comments of John T. Loughran at Memorial Proceedings for Chief Judge Lehman, in 294 N.Y. at xiv (quoting remarks made by Pound to Loughran when the latter came on the Court in 1934).

- Lewis, supra note 47, at 28.

- Letter from Charles H. Desmond to William M. Wiecek, March 16, 1970.

- Letter from Raymond J. Cannon to William M. Wiecek, February 23, 1970.

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 157 58.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 286; Nevins, supra note 4, at 154 n*. “At times, however, he could turn his deafness to advantage: when counsel before him on the Court of Appeals insisted on pursuing a point that Lehman thought futile, but which one or more of his brethren wished to hear, he would snap off the receiver of the cumbersome amplifying mechanism that he used as a hearing aid and turn to reading briefs in another case.” Wiecek, supra note 2, at 286.

- Letter from Raymond J. Cannon to William M. Wiecek, February 23, 1970.

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 157.

- Samuel I. Rosenman, Irving Lehman, 6 Universal Jewish Encyclopedia 595, 595 (1948).

- Jerome Frank, Law and the Modern Mind 134 (1930) (“the conviction that justice will be done will be more certain when decisions are rendered by such judges as Holmes, Cardozo, Hutcheson, Lehman and Cuthbert Pound”).

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 289. In early 1939, Governor Herbert Lehman wrote President Roosevelt, urging him to appoint Irving Lehman to the Supreme Court. Such appointment, however, was a political impossibility, given geographic considerations and the fact that two New Yorkers already sat on the Supreme Court at that time (Charles Evans Hughes and Harlan Fiske Stone). Id.

- See Shientag, supra note 3, at 157 (“As the years passed his judicial service grew in distinction. Not only was his range of learning and insight widened; he developed a moral power, a social viewpoint and a largeness of humanity, that carried him high toward the peak of judicial statesmanship.”).

- Irving Lehman, The Influence of the Universities on Judicial Decision, 10 Cornell L.Q. 1, 1 3 (1924).

- See, e.g., Irving Lehman, Address Before the N.Y. County Lawyers’ Association, in 1928 N.Y. County Law Ass’n Y.B. 295, 297 (1928) (“The thoughtful judge learns soon after he takes his seat upon the bench that men’s conduct is capable of infinite number of variations and that exact justice cannot be done in all cases through the application of general rules which do not recognize such variations. . . . [T]he law . . . has remained a living force because it has been capable of changing, growing and developing as conditions have changed, as men’s wisdom has grown from experience”).

- Lehman, supra note 45, at 12 (describing respect for precedent as the recognition of “progress along a road where the great traditions of the common law can still serve as guideposts”).

- Rosenman, supra note 59, at 595. See, e.g., People ex rel. Consolidated Water Co. v. Maltbie, 275 N.Y. 357, 365 (1937) (Lehman, J.) (“Earlier decisions may guide judgment in analogous cases; they are not intended to constrain judgment under circumstances where reason points to other conclusions.”), appeal dismissed, 303 U.S. 158 (1938).

- Lehman, supra note 64, at 297; see also Irving Lehman, Technical Rules of Evidence, 26 Columbia L. Rev. 509, 512 (1926) (“the desire for uniformity in the law is in conflict with the need of elasticity in its administration and application”).

- Lehman, The Influence of the Universities on Judicial Decision, supra note 63, at 3.

- Grant Gilmore, Ages of American Law 77 (1977). Gilmore used this phrase to describe the “furor” caused by the publication of Benjamin Cardozo’s The Nature of the Judicial Process in 1921 and how his “hesitant confession that judges were, on rare occasions, more than simple automata, that they made law instead of merely declaring it, was widely regarded as a legal version of hard core pornography.” Id.

- See id. at 68 91; Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law 688 692 (1985).

- See Lehman, The Influence of the Universities on Judicial Decision, supra note 63, at 12 (“The courts that keep abreast with the thought of the times recognize that their function is not to pass upon legislative discretion, but upon legislative power. They may set no limits to legislative power but must give effect to the limits set by the constitution.”).

- See, e.g., Kraus v. Singstad, 275 N.Y. 302, 312 (1937) (Lehman, J., dissenting) (recognizing legislative power to address emergencies, by contending that Legislature was authorized to create emergency positions outside the civil service notwithstanding State Constitution’s command that all civil service appointments be “according to merit and fitness”); People ex rel. Tipaldo v. Morehead, 270 N.Y. 233, 239 (Lehman, J., dissenting), aff’d, 298 U.S. 587 (1936) (dissenting from decision to strike down statute authorizing New York Industrial Commission to fix minimum wage for women and children).

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 281.

- Id.; G. Edward White, The American Judicial Tradition 178 (1976). The conservative bloc on the Supreme Court – also known in contemporary media accounts as the “Four Horsemen”- consisted of Willis Van Devanter, Pierce Butler, James C. McReynolds, and George Sutherland. Id.

- William M. Wiecek, Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement Three, 1941 1945, at 451.

- See, e.g., Irving Lehman, An Address by Irving Lehman Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, in The Supreme Court of the State of New York _ 1691 1941 _ Exercises Upon the Occasion of the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of Its Founding 42 (1941) (“The inalienable rights with which the Creator has endowed all men, are guaranteed by our Constitution – not created by it.”).

- See Wiecek, supra note 2, at 299 302 (reviewing representative decisions of Lehman’s involving civil liberties); Nevins supra note 4, at 154 n* (noting that Lehman was a “zealous champion of civil liberties”). Lehman’s approach to constitutional law – one which urged restraint if economic interests were infringed and increased judicial intervention where civil liberties were at stake – foreshadowed Justice Harlan Fiske Stone’s famous footnote 4 in United States v. Carolone Products Co., 304 U.S. 144, 152 53 n. 4 (1938). It may not be a coincidence that the day after Carolene Products was handed down by the United States Supreme Court, Stone wrote Lehman to express his growing concern about infringements of civil liberties abroad as well as in the United States. See Alpheus Thomas Mason, Harlan Fiske Stone: Pillar of the Law 515 (1956) (quoting letter from Justice Stone to Lehman: “I have been deeply concerned about the increasing racial and religious intolerance which seems to bedevil the world, and which I greatly fear may be augmented in this country.”).

- 279 N.Y. 523, 533 (1939) (Lehman, J., concurring). Lehman is said to have been proudest of his opinion in Sandstrom. Lewis, supra note 46, at 19 20.

- Minersville School Dist. v. Gobitis, 310 U.S. 586 (1940).

- West Virginia State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnett, 319 U.S. 624 (1943). Lehman’s disagreement with the Supreme Court in religious liberty cases was brought into sharp relief in People v. Barber, 289 N.Y. 378 (1944). There, writing for a unanimous Court of Appeals, Lehman ruled that the state lacked power to require peddler’s licenses of religious proselytizers who sold Bibles or religious pamphlets door to door. A few years earlier the United States Supreme Court had arrived at a contrary conclusion under the U.S. Constitution. See Jones v. Opelika, 316 U.S. 584 (1942). Lehman, however, concluded that Supreme Court precedent was not dispositive because the Court of Appeals was bound to exercise its independent judgment under the New York State Constitution. See Barber, 289 N.Y. at 384 (“Parenthetically we may point out that in determining the scope and effect of the guarantee of fundamental rights of the individual in the Constitution of the State of New York, this court is bound to exercise its independent judgment and is not bound by a decision of the Supreme Court of the United States limiting the scope of similar guarantees in the Constitution of the United States.”).

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 299. In a 1945 speech to the New York State Bar Association, Lehman stated with respect to criminal proceedings: “The Court may not sanction any proven violation of a legal right or proven denial to any person of the freedom guaranteed by the constitution . . . .” Comments of John Sears at Memorial Proceedings for Chief Judge Lehman, in 294 N.Y. at x (quoting Lehman).

- 246 N.Y. 409, 429 (1927) (Lehman, J., dissenting). See also People v. Malinski, 292 N.Y. 360, 376 (1944) (Lehman, C.J., dissenting), rev’d, 324 U.S. 401 (1945) (finding that trial court erred by instructing jury that in considering the voluntariness of a defendant’s confession jury it could consider a delay in arraignment, if it found such to exist, when such delay had been conclusively established and that the question was not for the jury to decide).

- Doran, 246 N.Y.2d at 436 37.

- This practice was engineered by leaders of the bar following a contested election for Chief Judge in 1913 between two sitting associate judges: Willard Bartlett and William Werner. That election, which was divisive within the Court and troubling to the bar, led to “a ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ among Democratic and Republican leaders to nominate jointly the senior associate judge for any future vacancy in the chief judgeship.” Kaufman, supra note 41, at 178.

- McKenna, supra note 2, at 438; Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 87.

- Mrs. Lehman Dies; Jurist’s Widow, 70, N.Y. Times, Feb. 18, 1950, at12.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 287 88; Nevins, supra note 4, at 153 54, 205.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 288 89; Nevins, supra note 4, at 218 19.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 288 89.

- Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 87.

- Promotion for Merit, N.Y. Times, May 10, 1939, at 22.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 288 89; Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 87 88.

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 204 (describing LaGuardia as being “hotheaded,” “impulsive,” often losing his temper and “lash[ing] out at anyone who displeased him-calling his opponents bums, punks, and reptiles . . . .”).

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 289. Thomas D. Thacher served as an Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals from 1943 to 1948.

- See Alan Brodsky, The Great Mayor: Fiorello La Guardia and the Making of New York City 123 (2003) (describing LaGuardia’s efforts as a Congressman to curb anti Semitism in certain nations following World War I). La Guardia himself “was a man of many religions. His father was a lapsed Roman Catholic, his mother a nonpracticing Jewess, his first wife a devout Catholic, his second a Lutheran, and he himself an observant though unconfirmed Episcopalian.” Id. at 3.

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 205.

- Id. at 154. Professor Rudolf B. Schlesinger, who clerked for Lehman from 1942 to 1944, noted “with humor that when he became a clerk he truly understood the depths and reality of the concept of the judge king.” Vivian Grosswald Curran, Fear of Formalism: Indications From the Fascist Period in France and Germany of Judicial Methodology’s Impact on Substantive Law, 35 Cornell Int’l L.J. 101, 164 n.310 (2001) (citing Rudolf B. Schlesinger, Reflections of a Migrant Lawyer, in Der Einflub deutscher Emigranten auf die Rechtsentwicklung in den USA und in Deutschland 487, 488 (Marcus Lutter et al. eds., 1993).

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 154 n*.

- See Shientag, supra note 3, at 174 (“Benjamin N. Cardozo was perhaps the most intimate and beloved friend Irving Lehman had.”).

- See June Bingham, A Genius Offers Advice on Love, The Riverdale Press, Feb. 3, 2000 (describing Einstein’s stay at the Lehman’s home in 1934).

- Letter from Herbert Lehman to Louis Nizer, Oct. 22, 1947.

- Comments of John T. Loughran at Memorial Proceedings for Chief Judge Lehman, in 294 N.Y. at xiv (“Irving Lehman was a singularly happy man. All in all, the course of his life ran quite consistently through pleasant places”).

- June Bingham Birge, Address Commemorating The 100th Anniversary of Irving Lehman From Columbia Law School, at 1 3 (Oct. 8, 1998).

- Shientag, supra note 3, at 158 (“A great source of Irving Lehman’s inward strength was his deep rooted religious faith.”)

- Rosenman, supra note 59, at 596.

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 205.

- Lehman donated his Judaica collection to Congregation Emanu El. See Cissy Grossman, A Temple Treasury: The Judaica Collection of Congregation Emanu El of the City of New York (1989).

- Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 85. Lehman owned several homes, including a house in Manhattan, the estate in Port Chester and a house in Albany. Nevins, supra note 4, at 205; Letter from Raymond J. Cannon to William M. Wiecek, February 23, 1970, at 3.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 283.

- Id.

- Id. at 284.

- Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 89 92.

- Morton Rosenstock, Louis Marshall: Defender of Jewish Rights 161 (1965).

- Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 91.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 283 84; Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 91.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 283; Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 89; Shientag, supra note 3, at 159.

- Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 91.

- See William M. Wiecek, The Encyclopedia of New York State 881 (2005) (describing Lehman as one of the nation’s most eminent state jurists).

- Irving Lehman, Address Delivered at Citizenship Rally on the Central Park Mall (June 25, 1939); 20,000 at Park Fete for ‘Young Citizens’, N.Y. Times, Jun. 26, 1939, at 18.

- Irving Lehman, Youth and Civic Responsibility, An Address Delivered On Radio Over the National Broadcasting Company (Sept. 16, 1939).

- The ceremony was memorialized in a beautiful book published by Herbert Lehman’s brother in law, Frank Altschul, the owner of the Overbook Press. See The Supreme Court of the State of New York _ 1691 1941 _ Exercises Upon the Occasion of the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of Its Founding (1941).

- See Hail State Court, 250 Years Old, N.Y. Times, May 29, 1941, at 20.

- Id. Arthur Lehman Goodhart was a scholar and legal philosopher of the first rank whose main interest lay in the common law. He helped found the Cambridge Law Journal and in 1926 became the editor of the prestigious Law Quarterly Review, a position he held for fifty years. Of Professor Goodhart’s many achievements, perhaps the most notable was his appointment in 1951 as Master of University College, Cambridge University, serving as the first American to head an Oxbridge college.

- See Schneiderman, supra note 10, at 90 (“He was profoundly moved by the calamity which engulfed the Jews of Germany and then the Jews of most of Europe during the Nazi tyranny . . . .”); Comments of John T. Loughran at Memorial Proceedings for Chief Judge Lehman, in 294 N.Y. at xiv (“I know how at the last his spirit was plagued by an acute awareness of the sufferings which those who were his kin in blood were made to endure in foreign lands.”).

- Nevins, supra note 4, at 243.

- Alexander Feinberg, General Stresses Devotion to Peace, N.Y. Times, June 20, 1945, at 6.

- Lewis, supra note 46, at 32.

- Edmund H. Lewis saw in the welcoming address “the vivid, flaming spirit of Irving Lehman the man, the great humanitarian.” Id.

- Wiecek, supra note 2, at 290; Nevins, supra note 4, at 308.

- Wiecek, supra note 75, at 452.

- The permanent record of the Court’s memorial service was published at 294 N.Y. at pages vii xiv.

- “1,100 at Memorial to Judge Lehman,” N.Y. Times, Nov. 26, 1945, at 34.

- Id.