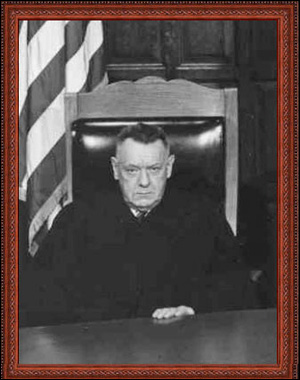

In Oliver Goldsmith’s “She Stoops to Conquer,” Hardcastle observes that “modesty seldom resides in a breast that is not enriched with noble virtues. It was the very same feature in his character that first struck me.” Hardcastle might have been describing Judge Sydney F. Foster. He is one of a small handful of Court of Appeals judges whose portrait does not repose in Court of Appeals Hall. Reasons for these missing portraits vary; in Judge Foster’s case it was his own steadfast refusal. His former law clerk, Professor Sanford H. Levine explains:

Judge Foster served on the Court of Appeals as an Associate Judge until he reached mandatory retirement, a period of four years. Toward the end of that service, I asked him about his plans for offering his portrait to the Court following long-standing tradition. He responded to me in the same manner as he would do at his retirement ceremony at the Court in December of 1963: ‘I am well aware that I have contributed but very little to the legal lore of this court. . . .'(13 NY2d at viii.) No amount of reasoning to the contrary would change his mind and we have all respected his wishes. His official portrait therefore is absent from Court of Appeals Hall.

The quality of Judge Foster’s modesty gives this an added meaning, considering that when the Judge retired at age 70 from the Court of Appeals, Chief Judge Charles S. Desmond called him “one of the best known and most admired appellate jurists of New York History.”1

For most lawyers and judges, a 14-year term on the State Supreme Court is a distinction. In what must be a record, Judge Foster was elected three times to 14-year terms and appointed and reappointed to the Appellate Division by four governors, twice as Presiding Justice.

He started early enough winning his first seat on the Supreme Court at age 35. When he died in 1973, Judge Foster had served on the bench for four decades and was a member of the state’s first administrative body, the judicial conference.

Sydney Francis Foster was born in Cazenovia, Madison County, New York, on March 23, 1893, where his father was a farmer. He was graduated from Cazenovia Seminary in 1911. While there, he acquired his love of the law working in the office of Justice Michael H. Kiley. He spent a year as an undergraduate at Syracuse University before entering its law school in the fall of 1912. As a law student, he was elected to Phi Delta Phi, an honorary legal fraternity.

After graduating in 1915, he took a job as deputy county clerk in Madison County, where he served from 1916 to 1918, having been admitted to the bar in 1917. When World War I broke, out Foster enlisted on the American Expeditionary Forces, serving in the Judge Advocate General Unit in France.2

After completing his military service in November 1920, Foster moved to Sullivan County, which was to be his home for the rest of his professional life. He joined the law office of Joseph Rosch, who the very next year became a State Supreme Court Justice. Foster then became partners with William A. Williams.3

In 1924, he married Mabel Angel of St. Johns Newfoundland, and the next year was elected district attorney, succeeding Henry F. Gardner, and defeating William Deckelman. In 1926, he was a delegate to the Republican Party’s State Convention. On November 8, 1928, the New York Times reported that district attorney Foster, elected as a Supreme Court justice for the Third Judicial District, was believed to be the youngest person ever chosen for that office in New York State.4

On the Supreme Court, Foster traveled the Third Judicial District, which included Greene County. There he presided over the trial of Manning Strewl who had been charged with kidnapping 24-year-old John J. O’Connell Jr., the nephew of Albany’s famous political leader Daniel P. O’Connell. In January 1937, Justice Foster sentenced Strewl, in one of New York’s most publicized cases. Strewl was said to have “won a fifteen year sentence from Judge Foster” after pleading guilty to blackmail as a substitute for the fifty-year term imposed on him earlier for the 1933 abduction.5

In September 1939, Governor Herbert Lehman temporarily designated Judge Foster as a member of the Appellate Division, Third Department. Three years later Foster won his second election as Supreme Court Justice for the Third Judicial District.

The following year a political battle took place in which the Republican Party sought to fill the post of Lieutenant Governor, owing to the death of Thomas W. Wallace, who held the post. At the trial level, Justice Foster ruled with the Democrats, concluding that an election was required. His ruling was affirmed by the Appellate Division and Court of Appeals.6

In 1944 Judge Foster was again appointed to the Appellate Division, this time by Governor Dewey, who named him Presiding Justice in 1949. By that time Judge Foster had been in public service for almost a quarter century, and was recognized by his alma mater Syracuse University, which awarded him an honorary degree in 1950. The following year the Syracuse Law School Alumni Association honored him with its Distinguished Service Award.

In the early 1950s, Judge Foster played an active role in court administration as the Judiciary began to recognize that the system had grown too large to be managed without reorganization. In 1953, after meeting with Justice Foster and the other three Presiding Justices of the Appellate Division, Governor Dewey recommended court reform.7

Arising out of the same concerns, the judiciary formed the Judicial Conference, forerunner to the Office of Court Administration,8 consisting of the four Presiding Justices, David W. Peck, First Department, Gerald Nolan, Second Department, Sydney Foster, Third Department, and Francis McCurn of the Fourth. The Conference interacted with the Temporary State Commission on the Courts (known as the Harrison Tweed Commission) in promoting modernization of the judicial branch.9

Judge Foster would not have been on the Judicial Conference or the Appellate Division had he succeeded in the 1954 election for a seat on the Court of Appeals. Designated as the Republican candidate, he was strongly supported by the bar associations and editorial writers but was defeated for the seat.10 Adrian Burke, the Democratic-Liberal candidate, was successful by a vote of 2,411,646 to 2,554,870.11

When it came to his own region of the State, however, Judge Foster succeeded for the third time in his candidacy for Supreme Court, in November 1956, and Governor W. Averell Harriman redesignated him Presiding Justice. In the late 1950s, Judge Foster was a strong advocate of court reorganization,12 favoring a court decongestion plan advanced by Judge Desmond in which lawyers, by the consent of both parties, would sit as part-time judges.13

A second chance for a seat at the Court of Appeals came in the 1960 election. At the beginning of that year, Governor Nelson Rockefeller redesignated Foster Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, Third Department. A vacancy existed in the Court of Appeals when Judge Desmond was elevated to Chief Judge, and Governor Rockefeller appointed Judge Foster to fill it until the November election, while the political parties considered whom they would nominate.

Judge Foster was the Republican nominee; the Democrats chose Judge Henry L. Ughetta of the Appellate Division, Second Department. That year, the Liberal party had enough votes to decide close elections. The party had always supported Democrats, but in this instance broke tradition and backed Judge Foster.14 It made the difference, as Judge Foster won the election.15 Judge Foster’s service on the Court was regrettably short. He was forced to retire in 1963, when he reached age 70.

Judge Foster authored 47 majority opinions during his time on the Court. His writings reflect a marked degree of commonsense and fairness, accompanied by a distaste for vagueness. This sensibility is evident in People v. Post Standard Co. (13 NY2d 185 [1963]), Ass’n for Preservation of Freedom Choice, Inc. v. Shapiro (9 NY2d 376 [1961]), and Nash v. Kornblum (12 NY2d 42 [1962]). Post Standard Co. involved a contempt of court prosecution brought against a newspaper for publishing an incorrect account of court proceedings. Citing the principle that “an intent to defy the dignity and authority of a court is a necessary element of a criminal contempt” (id. at 190), Foster, writing for the Court over a dissent by Chief Judge Desmond, concluded that the charges should be dismissed. He reasoned that, absent an intent requirement, newspapers would face liability

for criminal contempt on the basis of a false publication without regard to any intent to impinge upon the dignity of the court or to interfere with the administration of justice. It would permit a conviction for the slightest falsity, irrespective of whether such deviation from the actual facts is intentional or merely inadvertent, significant or insignificant, and proximate or remote.

Foster also rejected the notion that the mere publication of incorrect facts represented an assault on the dignity of judicial proceedings.

In Ass’n for the Preservation of Freedom of Choice, Inc. v. Shapiro (9 NY2d 376 [1961]), the plaintiff group sought to incorporate in New York. Their certificate of incorporation required the approval of a Justice of the Supreme Court, and such approval was not forthcoming. The Justice determined that, although the group’s stated purposes-to promote the right to individual freedom of association and to foster a multicultural society-were lawful, it nevertheless was not entitled to incorporate. Writing for the Court over dissents from Judges Burke and Froessel, Judge Foster surmised that the Justice’s denial of approval “was based upon public policy, or injury to the community, or both, as envisaged by the Justice before whom the matter was placed” (id. at 381). Foster regarded as nonsensical the proposition that a corporate purpose could violate public policy when it was not unlawful:

To hold otherwise would be a contradiction in terms. . . . [T]he test as to what may be injurious to the community is too vague, indefinite and elusive to serve as an objective judicial standard. Within such a scope the individual Justice would be at liberty to indulge in his own personal predilections as to the purposes of a proposed corporation, and impose his own personal views as to the social, political and economic matters involved. This is the direct antithesis of judicial objectivity, especially in an ex parte proceeding where no evidence has been taken.

In Nash v. Kornblum (12 NY2d 42 [1962]), the Court granted reformation of a contract when an essential term in the contract differed from the term as originally agreed on orally. The parties had agreed to the installation of 484 linear feet of fencing, but the written contract provided for 968 linear feet. Writing for the Court, Foster identified the case as one of “a mistake on the part of the plaintiff’s agent in typing the erroneous linear ground measurement, which plaintiff did not discover before submission to the defendant, and the latter, with knowledge of the mistake, trying to take advantage of the error” (id. at 47). The written contract, Foster observed, “did not represent the understanding of either party as to the area to be fenced which had been agreed upon previous to the writing, and thus did not embody the true agreement, as mutually intended, relating to the area.” Therefore, the contract could not be enforced as written.

Of particular note was his Appellate Division dissent in Commercial Pictures Corp. v. Regents of University of New York (280 App. Div. 260 [3d Dep’t 1952]). The case turned on whether the Board of Regents properly refused to license a film named LaRonde. The Appellate Division majority upheld the refusal. Judge Foster disagreed, saying:

Since freedom of expression is the rule and any limitation thereof may only be exercised in exceptional cases the statute under which the Regents acted can hardly be envisaged as the “clearly drawn statute” which the Supreme Court mentions. Except for news, educational and scientific films it confers a broad power of censorship. In dealing with an issue of free expression the determination of any board or bureau should only be upheld where it is clear that any conclusion to the contrary would not be entertained by any reasonable mind. Since a constitutional issue is involved litigants should be entitled to the independent judgment of a competent court after the event.

…

In the present case the film in questions is certainly not obscene. It has been condemned on the ground that it is ‘immoral’ and its presentation ‘would tend to corrupt morals.’ True it deals with illicit love, usually regarded as immoral. But so is murder. The theme alone does not furnish a valid ground for previous restraint.

The Court of Appeals affirmed but the United States Supreme Court reversed, vindicating Judge Foster’s views16

After leaving the Court when he turned 70, Judge Foster spent the next five years as a trial judge, taking assignments where needed. At age 80, he died in Lakeland, Florida, survived by his wife who died in 1980. Judge Foster is buried in Liberty Cemetery. No amount of modesty can diminish his noteworthy career.

Progeny

In 1925, Judge Foster married Mabel Angel, who survived his death in 1973, as did a sister, Julie M. Foster of Cazenovia, who died in 1987 at age 93. The Judge’s only child, a son, Richard A. Foster married Sally Patricia May on June 27, 1953 in Ann Arbor, Michigan.17 He was an assistant attorney general from 1956 to 1963 and again from 1968 to 1972. From 1970 to 1972, he argued several cases in the Court of Appeals and Appellate Division. In retirement, he lives in Roswell, Georgia. He and his wife have three children: Bruce Sydney Foster, a policy analyst with the Wage and Investment Headquarters Division of the Internal Revenue Service; Glen Foster, a computer technician; and Dawn Foster, a marriage and family therapist. All three reside in Roswell, Georgia.

Bruce S. Foster has three children: Theresa Katherine, 18; Rachel Ashley, 14; and Zachary Richard, 12.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Conway, John, Remembering a Distinguished Judge, Times Herald Record, Jan. 22, 1992.

In Memoriam, Proceedings held at the Courthouse in the Village of Monticello, New York in the 2nd day of February 1974.

Obituary, New York Times, Nov. 23, 1973, p. 39, “Sydney F. Foster, A Retired Judge, Member of State Court of Appeals, Dead at 80.”

Obituary, Nov. 21, 1973, “Rites Held for Judge Sydney Foster,” (name of newspaper unknown).

Obituary, Nov. 21, 1973, “Former Liberty Justice Dies,” (name of newspaper unknown).

Syracuse University Alumni News, Dec. 1928.

Syracuse University Alumni News, Dec.B Jan. 1940 (article by David F. Lee, ’07).

Endnotes

- 13 NY2d vii (1963).

- John Conway, Sullivan Retrospect, Remembering a Distinguished Judge. Times Herald -Record, Jan. 22, 1992, p. 4; Syracuse Alumni Publication, Dec. 1928.

- Williams, who became Mayor of Liberty, died in 1931. New York Times, Sept. 24, 1931, p. 22.

- New York Times, Nov. 8, 1928, p. 3.

- New York Times, Jan. 16, 1937, p. 4. For an account of the kidnapping, see People v. Strewl, 240 App. Div. 400 (3rd Dep’t 1936), reversing the original conviction. Strewl and other defendants had been prosecuted federally as well. After serving 24 years, Strewl was released in 1958 and died 40 years later at age 95. O’Connell, the kidnap victim, died in 1954.

- See Ward v. Curran, 266 App. Div 524, aff’d 291 NY 64 (1943). See also, New York Times, Aug. 18, 1943, p. 1; New York Times, Aug. 20, 1943, p. 1.

- New York Times, Jan. 4, 1953, p. 46.

- New York Times, Nov. 13, 1955, p. 80.

- New York Times, Jun. 23, 1956, p. 1.

- New York Times, Oct. 18, 1954, p. 17; Oct. 28, 1954, p. 21; Oct. 29, 1954, p. 22; Oct. 31, 1954, p. 53. The New York Times lamented the loss (Nov. 4, 1954, p. 30).

- New York Times, Dec. 17, 1954, p. 26.

- New York Times, Jun. 23, 1956, p. 1; Nov. 15, 1956, p. 37; Feb. 13, 1957, p. Jan. 15, 1958, p. 1; Nov. 10, 1958, p. 1.

- New York Times, Nov. 15, 1956, p. 37.

- New York Times, Sept. 20, 1960, p. 1.

- New York Times, Nov. 9, 1960, p. 1, p. 26. The Times supported him editorially. See, New York Times, Nov. 4, 1960, p. 32.

- See Commercial Pictures Corp. v. Board of Regents of N.Y., 305 NY 336 [1953], rev’d, sub nom Superior Films, Inc. v. Department of Education, 346 US 587 (1954). Judge Foster may have had his limits. Earlier, he had written to the Appellate Division in its unanimous ban of the film “The Miracle” (Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 278 A.D. 253 [1951], aff’d 303 N.Y. 242 [1951], rev’d 343 U.S. 495 [1952]. He concluded that the work was sacrilegious and offensive to many. By 1956, however, after the Supreme Court’s refusal in Burstyn, he outdistanced his colleagues by concurring in Excelsior Pictures Corp. v. Regents of University of State of N.Y., 2 A.D. 941 (3rd Dep’t 1956) saying that he would declare outright that New York’s censorship statute is unconstitutional.

- New York Times, July 5, 1953, p. 46.