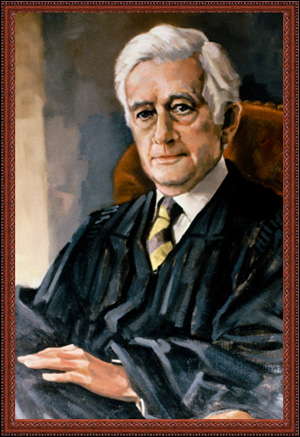

The life of Kenneth Barnard Keating-as teacher, lawyer, soldier, legislator, judge, and diplomat-spanned the first 75 years of the Twentieth Century. He was an unabashed patriot who devoted most of his adult life to service to his country and his native New York State. While his tenure as an associate judge of the Court of Appeals was comparatively brief, “[he] was an activist judge whose prominence in American life allowed him to have an impact on the Court which was uncommon for a junior member of the bench.”1 Indeed, his work was significant enough to warrant scholarly praise and at least one doctoral thesis.2 Ken Keating is likely to be most remembered in popular history as the freshman United States Senator from New York who first alerted the country to the presence of Soviet offensive missiles in Cuba and who, on the domestic front, occupied a key leadership role in the bipartisan Senate coalition that broke through a filibuster to achieve the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Ken Keating was above all an affable man who was admired and respected by all who knew him. Almost uniquely in a public career of long duration, his detractors were few.

He was born in Lima, Livingston County, New York, on May 18, 1900, the son of Thomas Mosgrove and Louise (Barnard) Keating; attended the public elementary schools; and graduated from Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in Lima in 1915 and from the University of Rochester (A.B., Phi Beta Kappa), in 1919, with service in-between as a sergeant in the United States Army during World War I. Too young to meet the admission requirements at most law schools in that era, he served as an instructor in Latin and Greek at the East High School, Rochester, for two years before entering Harvard Law School, where he obtained his LL.B. degree in 1923. He was admitted to the New York bar and began the practice of law in Rochester. For most of the pre-World War II period, he was a member of the Rochester firm of Harris, Beach, Folger, Bacon & Keating. He achieved great professional distinction at the bar in those years and his many contributions to the civic life of his community enhanced his reputation for public-spirited service.

During World War II, although past the age of conscription, he returned to active military service, rising in rank to colonel. He served three years overseas, most notably in the China-Burma-India Theater. Among other recognitions, he was awarded the Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster, the American, European and Asiatic Theater Ribbons with three battle stars, and the Order of the British Empire. After returning from the war, he remained in the reserves and was promoted to the rank of brigadier general in 1948.

In civilian life, Keating, a lifelong Republican, was a member of the New York delegation to every Republican National Convention from 1940 to 1964. Along the spectrum of party politics in postwar America, he was generally regarded as belonging to the Eastern, or internationalist, wing of the Republican Party, identified with strong national security concerns in the Cold War, a centrist in domestic economic and social policy, and a liberal in civil and human rights. He was elected as a Republican to the House of Representatives in the Eightieth and the five succeeding Congresses, his tenure spanning from January 3, 1947, to January 3, 1959. Keating’s ever-increasing margins of victory at the polls convinced state party leaders and the Eisenhower administration that he should run for United States Senate in 1958. At the Republican state convention in Rochester, Keating accepted the candidacy, although it meant risking his safe House seat in a contest that he was uncertain of winning.

The 1958 election year was marked by significant Democratic gains in the Congress as well as in state-level offices. There were two important exceptions: in New York, where Nelson A. Rockefeller, at the top of the Republican slate, was elected Governor of New York, helping his fellow candidate Representative Keating to gain election to the United States Senate; and Arizona, where Barry Goldwater, a member of his party’s conservative wing, was also elected to the Senate.

In the Senate, Keating distinguished himself as a freshman member. He played a major role in the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, sponsored legislation leading to the adoption of the 23rd Amendment, which enfranchised the District of Columbia, and he repeatedly voiced concern over the repressive Soviet-backed dictatorship of Fidel Castro. Indeed, as early as July 1961, more than a year before the Cuban Missile Crisis, he asked his colleagues in the Senate: “How long will it be before the Soviet Union establishes military bases and missile launching sites in Cuba?”3 Then in October 1962, relying on information provided by officials of the CIA, the Pentagon as well as Cuban exiles, he exposed the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba. Although at first the Kennedy White House dismissed Keating’s warnings about those missiles, U-2 flights confirmed Soviet deployment. Thus began the most dangerous nuclear confrontation of the Cold War.

In the 1964 Republican National Convention, Senator Goldwater became his party’s candidate for president, defeating the bid of Governor William Scranton of Pennsylvania, the nominee of what had by then become known as the Rockefeller wing and, by way of contrast, the “liberal” wing of the G.O.P. Dominated by conservative delegates, the convention ill-treated Rockefeller and Keating during their platform appearances in support of Scranton and, following the final nomination of Goldwater by acclamation, in an incident prominently shown to the national television audience, Senator Keating led the New York delegation out of the San Francisco Cow Palace in the midst of jeers and catcalls. In the 1964 presidential election, President Lyndon Johnson defeated Senator Goldwater in a landslide, while Robert F. Kennedy, though running two million votes behind Johnson on the Democratic ticket in New York, defeated Senator Keating’s attempt to win a second term.

In 1965, Keating returned to the practice of law in New York City as a member of the internationally prominent firm of Royall, Koegel & Rogers – in partnership with his longtime friend and political ally, William P. Rogers, the former U.S. Attorney General who had served under President Eisenhower. The ex-Senator’s practice was highlighted by his appointment by United States District Judge Harold R. Tyler, Jr. to serve as a trustee in bankruptcy for the now long-gone Railway Express Agency. The year 1965 was an off-year election cycle for national and other statewide offices. Nevertheless, it was an important year for statewide judicial and municipal offices. Because Keating remained a particularly popular figure in New York, he was pressed to head the Republic state ticket that year as its nominee for election to the New York Court of Appeals. Within the City of New York, that was to team him with U.S. Representative John V. Lindsay’s candidacy to break the long stranglehold of the Democratic Party on the New York City mayor’s office. Keating and Lindsay both prevailed. Keating’s prominence as a United States Senator contributed to his winning the seat on New York’s highest court by the largest margin of victory ever attained in a contested statewide election since Herbert H. Lehman, a revered name in New York politics, gained the governorship in 1932.

Judge Keating was foreordained to a short tenure on the Court of Appeals. Under the New York State Constitution, persons elected to judgeships on the Court of Appeals nominally serve in office for a 14-year term but are subject to mandatory retirement at age 70. Judge Keating, who took office as he approached age 66, nevertheless made his mark upon the law and upon the Court. In little more than three years in office, Judge Keating wrote 100 opinions. As Chief Judge Breitel observed: “Although he was only on the Court of Appeals a comparatively short time, his contributions in both majority opinions and dissenting opinions were outstanding. His approach was novel and dynamic. The opinions he wrote were done in a style that was unusually graphic. They always made good reading whether one agreed with him or not.”4

Judge Keating’s career as a legislator and politician strongly influenced his approach to his work as a judge. “[W]ith a legislator’s affinity for constituent service and schooled in the give-and-take of congressional committee law-making, [he] behaved on the bench in a manner significantly different from his brethren.”5 Specifically, his years in the legislative branch imbued in him a general restlessness with the traditional judicial approach to decision-making. As he once observed:

“[A] judge whose entire career has been in elective office and who has been charged with the responsibility of solving problems and producing results may be less inclined to bow to precedent or notions of judicial restraint when faced with problems long neglected and susceptible to judicial resolution.”6

Generally, precedent was to be followed on any point of major significance only if it made sense in the context of the case and the times. He had little patience with distinguishing cases which the Court was really overruling. Many times, both privately and in his opinions, he was critical of those attempts to overrule cases by distinguishing them. He regarded this practice as confusing to the bar, unnecessary and less than honest. Moreover, he was a judge, just as he was a politician, particularly receptive to change, to seeking to keep the law responsive to the needs of the present and unwilling to decide significant questions of public policy in a particular way merely because a different court sitting in a different time did so. This philosophy found expression in many cases and in many areas of the law.

In Liberty National Bank v. Buscaglia,7 he rejected the argument that because national banks were instruments of the federal government they should be exempted from the payment of non-discriminatory state taxes. The opinion carefully noted the changing nature of national banks since the landmark decision of McCullough v. Maryland,8 which had provided the basis for the tax-exemption argument. He concluded that there was no longer any real basis for following past decisions “which were relevant in another time and under different circumstances.”9

In Gallagher v. St. Raymond’s Roman Catholic Church,10 he wrote an opinion overruling the traditional common law rule which provided that an owner of a building to which the public was invited had no duty to illuminate the outside stairway, a rule which the court had only recently reaffirmed. The opinion noted that the common law rule was originally formulated at a time when gas lighting in the interior of buildings was far from universal and electric lighting of public streets had barely begun.

In the course of his opinion, he not only set forth an approach to the law but articulated a philosophy which guided many of his opinions:

It is saying the obvious but it bears repetition that whether a society will tolerate a particular course of conduct is, to a large measure, dependent upon the development of society at the particular moment when the courts are called upon to enunciate a standard of care. We can conceive of no reason why at the present time the owner of a public building should not be required to light the exterior of his building at those times when it is open to the public. The traditional rule no longer expresses a standard of care which accords the mores of our society. The public is entitled to a safe and reasonable means to enter and exit from an open public building. In this day and age, this should mean a lit path or stairway to the street.

. . . [T]he common law of this State is not an anachronism, but is a living law which responds to the . . . reality of changed conditions. We therefore do not hesitate to purify our law of what has, with the passage of time, become a most anomalous exception to the . . . common law rule of due care.11

Similar reasoning supported his opinion for the court in Millington v. Southeastern Elevator Co.,12 overruling the common law rule which denied a wife a right of action for loss of consortium-a rule which he found contrary to “the growing recognition that the law of torts must recognize the interest of persons in the protection of essentially emotional interests . . .”13

Opinions like these were the product of an activist approach that Judge Keating brought from his long legislative career. Some of them clearly and directly reflected his own experience in the legislative branch. Many times his opinions in favor of overruling a particular precedent were challenged as an encroachment upon the legislative domain. The Judge was unimpressed by such arguments especially where the issue was peculiarly within the province of a common law court. He felt that legislatures of both state and federal governments were “preoccupied with the overwhelming problems of public law, of raising revenue and providing the machinery for the numerous governmental programs designed to improve our society and way of life.”14 The inevitable result, however, “is that the problems of private litigants and the making and administration of private law is too often neglected.”15

Judge Keating knew that legislative action usually came in the area of private law only at the behest of a particularly strong special interest group and he was not about to stand by and apply irrational judge-made rules merely because the legislature had not acted to alter them. His opinion in Flanagan v. Mount Eden General Hospital,16 illustrates his approach. There the Court of Appeals overruled the traditional common law rule that the statute of limitations in malpractice actions, which involved instruments left inside a patient, began to run from the commission of the act. Writing for the court majority, Judge Keating again followed the approach of examining the rule in light of reason and concluded that continued adherence to it was unwarranted. He found that the policy of insulating defendants from the burdens of defending stale claims which could have been instituted more expeditiously was an unconvincing justification for the harsh consequences which resulted from applying the same concept of accrual in foreign-object cases as in medical treatment cases. “A clamp, though immersed within the patient’s body and undiscovered for a long period of time, retains its identity so that a defendant’s ability to defend a ‘stale’ claim is not unduly impaired.”17

The dissenting opinion charged that the majority was not only ignoring the rule of stare decisis but also a presumptive legislative intent. The dissent argued that a failure of the Legislature to change the common law rule despite general codification of the law in the area reflected a legislative determination that the rule remain unchanged. Judge Keating, aware of the dynamics of the legislative branch, rejected as purely speculative the argument that legislative inaction constituted legislative approval. More fundamentally he observed:

Our decision does not encroach upon any legislative prerogative. The Legislature did not provide that the Statute of Limitations should run from the time of the medical malpractice. This court did. Therefore, a determination that the time of accrual is the time of discovery is no more judicial legislation than was the original determination. Granted, the Legislature could have acted to change our rule; however, we would surrender our function if we were to refuse to deliberate upon unsatisfactory court made rules simply because a period of time has elapsed and the legislature has not seen fit to act.

Courts and legislatures need not be viewed as antagonists in the area of tort law. Developing the laws is a province of both and the particular attributes of these institutions are complementary in getting the task performed. Judicial action is often necessary to bring to the attention of the Legislature a particular problem in order for it to accomplish the necessary reform which only legislative action can fashion.

Where a court makes what appears to be a needed adjustment in an area in which the Legislature has failed to act, the Legislature is not thereby foreclosed from action.18

The threads that run through his majority opinions are also to be found in at least two notable dissenting opinions. In Walkovszky v. Carlton,19 the Court of Appeals addressed what appeared to be a common practice in the taxicab industry of vesting the ownership of a taxi fleet in many corporations, each owning one or two heavily mortgaged cabs and each carrying only $10,000 in personal liability insurance – the minimum legally required at the time. The majority of the Court of Appeals held that the individual who owned and incorporated each of the corporations was shielded by the corporate veil from liability in excess of the insurance coverage and the negligible assets of the corporate entity.

Judge Keating dissented. In so doing, he observed that “[f]rom the inception these corporations were intentionally undercapitalized for the purpose of avoiding responsibility for acts which were bound to arise as a result of the operation of a large taxi fleet . . . and during the course of the corporation’s existence all income was continually drained out of the corporations for the same purpose.”20 In his opinion, which is published in law school textbooks alongside the majority opinion,21 he argued that it was inequitable to allow shareholders to abuse the corporate privilege at the expense of the public interest.

In Riss v. City of New York,22 the Court of Appeals held that a municipality was not liable for failing to provide special protection to a member of the public who was repeatedly threatened with personal harm and eventually blinded when a thug hired by her former boyfriend threw lye into her face.

Judge Keating dissented. In a powerful opinion which the following paragraph only begins to capture, he wrote:

Linda [Riss] has turned to the courts of this State for redress, asking that the city be held liable in damages for its negligent failure to protect her from harm. With compelling logic, she can point out that, if a stranger, who had absolutely no obligation to aid her, had offered her assistance, and thereafter Burton Pugach was able to injure her as a result of the negligence of the volunteer, the courts would certainly require him to pay damages. (Restatement, 2d, Torts, ‘ 323). Why then should the city, whose duties are imposed by law and include the prevention of crime (New York City Charter, ‘ 435) and, consequently, extend far beyond that of the Good Samaritan, not be responsible? If a private detective acts carelessly, no one would deny that a jury could find such conduct unacceptable. Why then is the City not required to live up to at least the same minimal standards of professional competence which would be demanded of a private detective.23

This dissent as well made its way into law school textbooks.24

The foregoing opinions reflect Judge Keating’s approach to the case law with which a common law court is generally concerned. Different considerations are often present when the issue involves striking the balance between individual rights and liberties and the police and regulatory powers of government. The Judge’s philosophy in this area to a great extent reflected the traditional conservative concern with government overreaching-a philosophy which at the time placed him on the liberal side of the court.

Judge Keating’s opinions in the search and seizure area reflected that view and strictly limited government intrusion on the privacy of the individual.25 There were many decisions to that effect. One of the most significant was Narcotic Addiction Control Commission v. James,26 which struck down a part of the Narcotics Addiction Control Act permitting a defendant to be seized and held for examination without being advised of the charges against him and without being provided a hearing in which to attack the initial decision to restrain his liberty.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States provides that no person shall be deprived of liberty without due process of law. The detention of this appellant, who is charged with no crime, against his will for a period of three days without notice of the nature of the proceeding and an opportunity to contest the finding upon which the determination to restrain his liberty was predicated, is contrary to our most fundamental notions of fairness and constitutes a deprivation of liberty without due process of law.27

In Matter of Gregory W.,28 he likewise invoked the Due Process Clause in a landmark decision holding that juveniles accused of criminal activity could not be deprived of their freedom without being accorded the guarantees which the Constitution provided. In In re Gault,29 the Supreme Court would later rely upon what it characterized as Judge Keating’s “notable opinion” reaching the same conclusion in Matter of Gregory W.

The Judge’s decisions in the area of free speech also reflected his concern that government intrusion not stifle individual rights. In People v. Katz,30 perhaps the most significant free speech case to reach the Court of Appeals during his tenure, the Judge struck down a New York City ordinance which made it unlawful for any person to encumber or obstruct any street with any article or thing whatsoever. The defendants in that case were charged with erecting a three-foot-square table on a street in Queens as part of a protest against the Vietnam war. The table displayed various pamphlets with information relating to the Vietnam War.

Judge Keating concluded that by leaving it up to the individual police officer to determine what constituted an obstruction or encumbrance on a street, the statute was subject to arbitrary enforcement in accordance with the individual beliefs and prejudices of police officers:

It is, of course, appropriate for municipalities to enact legislation designed to promote general convenience on public streets. On the other hand, streets have always been recognized as proper places for the dissemination and the exchange of ideas . . . Where a statute is couched in such broad language that it is subject to discriminatory application, the resulting infringement on the exercise of freedom of speech far outweighs the public benefit sought to be achieved. While we are in sympathy with the general purpose of the statute involved in this case, its susceptibility to arbitrary enforcement and its use of total prohibition rather than reasonable regulation renders it unconstitutional.

A narrowly drawn ordinance can achieve the public convenience on the streets without sacrificing either individual constitutional rights or the public right to free discussion of matters of public concern.31

The Judge’s concern also extended to those incarcerated in state institutions. One of the Judge’s most important opinions-a vigorous dissent-involved the right of prisoners to communicate with their attorneys and government officials without censorship by prison officials. The Judge was critical of the majority’s decision upholding the right of the warden to censor “irrelevant material.” The Judge felt that attorneys and public officials who were recipients of letters from prisoners should be the ones to determine whether the contents were relevant and not a prison official whose conduct may be called into question:

The right of an individual to seek relief from illegal treatment or to complain about unlawful conduct does not end when the doors of a prison close behind him. True it is that a person sentenced to a period of confinement in a penal institution is necessarily deprived of many personal liberties. Yet there are certain rights so necessary and essential to prevent the abuse of power and illegal conduct that not even a prison sentence can annul them. As this court once observed, ‘An individual, once validly convicted and placed under the jurisdiction of the Department of Correction . . . is not to be divested of all rights and unalterably abandoned and forgotten by the remainder of society.’

Among the rights of which he may not be deprived is the right to communicate, without interference, with officers of the court and governmental officials; with those persons capable of responding to calls for assistance. No valid reason, other than the shibboleth of prison discipline, has been advanced for the denial of this right in the case before us.32

These cases reflected not only the Judge’s concern with unnecessary intrusions on individual rights but also his unflinching exercise of judicial power to strike down unreasonable government conduct. Here as in the ordinary common law cases, he believed that, if an independent judiciary stood by and did nothing, then only injustice would prevail. As one scholar observed after discussing Judge Keating’s work involving the rights of criminal defendants:

Judge Keating [was] a firm believer that society has a vital interest in arresting, prosecuting and convicting those suspected of crimes. Fortunately, however, unlike all too many members of the judiciary, he did not let this thought control his thinking as both man and a judge. In this he was judge of great integrity as well as one possessed of significant intellectual ability.33

While the decisions discussed above reflect the breadth of his contributions to the law during his tenure, Judge Keating’s most significant contribution to jurisprudence was in the field of conflict of laws. When he took his seat on the Court of Appeals, the choice-of-law rule in tort cases was in disarray and in other areas it was frozen in the past. Babcock v. Jackson34 had overruled the traditional choice-of-law rule which turned on the law of the place of the tort. Nevertheless, Babcock had been limited to its precise facts, if not completely overruled, in Dym v. Gordon.35 In little more than three years, beginning with his lone dissent in Macy v. Rozbicki,36 he led the Court of Appeals toward a choice-of-law rule that depended on an analysis of the policies and interests underlying the substantive law which rejected the application of the law of the place of the tort. Indeed, in Tooker v. Lopez,37 he persuaded Judge Burke, the author of the Dym v. Gordon,38 to cast the deciding vote in overruling it. As one scholar observed:

Judge Keating’s contribution to the evolution of the New York choice-of-law rule for torts is essentially that of a judicial statesman who joined a good but faltering cause and skillfully led it to a somewhat precarious victory. This alone is no mean feat; and it assures him a place in the annals of the law. His contribution to the development of New York’s choice-of-law rules in the “non-torts” areas, on the other hand, is nothing short of revolutionary. He introduced a completely new approach, [based on the governmental interest analysis], and he gained its unanimous acceptance.39

Because he would reach the mandatory retirement age for judges of the Court of Appeals in 1970, Judge Keating accepted the opportunity presented by the first Nixon administration to serve his country once more, this time as Ambassador to India, where he had seen service in World War II and its aftermath on the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. He resigned from the Court of Appeals in April 1969, officially took up his post in India on June 17, 1969, and served there until his resignation in August 1972 in order to be able to participate in that year’s presidential election campaign. During his posting to New Delhi, he confronted his severest challenge as a diplomat when war broke out between India and Pakistan, because his natural sympathy for the nascent Indian democracy stood in tension with an administration policy which tended to favor the interests of Pakistan as a Cold War ally.

In June 1973, more than a year before the dénouement of the Watergate crisis, Keating again answered the call to serve his country abroad, this time as President Nixon’s appointee as Ambassador to Israel. During the succession of President Ford, at the end of March 1975, Ambassador Keating left his post for home consultations on the reassessment of American policy in the Middle East. He fell ill that spring and died while hospitalized in New York City on May 5, 1975, weeks before he would have attained his 75th birthday. He was interred with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery, Fort Myer, Va.

“Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes in the Congress of the United States of the Life and Contributions of Kenneth B. Keating” appear in Senate Document No. 94-74, 94th Cong. 1st Sess. (U.S.G.P.O. Washington: 1975).40 The United States Government has further recognized the contribution of Kenneth B. Keating to a grateful nation in the erection and dedication of the Kenneth B. Keating Federal Building in Rochester, New York. The Judge Kenneth B. Keating Memorial Prize at Brooklyn Law School, established in his memory by two of his former law clerks in the New York Court of Appeals, is awarded to a member of each graduating class at that school whose exceptional achievement in the field of conflict of laws warrants recognition. During his lifetime, Kenneth B. Keating was the recipient of professional, civic, educational, religious, fraternal and other awards, honors and distinctions too numerous to mention. They bear testimony to an active, industrious, fulfilling, and most honorable life.

Progeny

Judge Keating and his first wife, the former Louise Dupuy who died in 1968, had one child, Judith (Mrs. James Howe of Short Hills, New Jersey) and two grandchildren: James E. Howe, a physician in Newton, Massachusetts; and David Keating Howe, of Oakland, California. In June 1974, less than a year before his death, Judge Keating married Mary Pitcairn Davis, a widow whose husband had been his classmate at Harvard. She survived him.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Baade, Judge Keating and the Conflict of Laws, 36 Brook. L. Rev. 10 (1969).

The Dirksen Congressional Center, Civil Rights: 1964, http://www.congresslink.org/civilrights/1964.htm.

Eminent Members of the Bench and Bar of New York 1943: CW Taylor Jr., Publisher.

Giannottasio, “The Judgeship of Kenneth B. Keating and the Limits of Judicial Reform.” Ph.D. dissertation, State University of New York at Stony Brook, 1994, available at http://wwwlib.umi.com/dissertations/cart?add’9522223.

Korman, Judge Keating: A Law Clerk’s Appraisal, 36 Brook. L. Rev. 3 (1969).

Memorial addresses and other tributes in the Congress of the United States on the Life and Contributions of Kenneth B. Keating.

Paterson, “The Historian as Detective: Senator Kenneth Keating, the Missiles in Cuba, and His Mysterious Sources.” Diplomatic History II (Winter 1987): 67-70.

Pitler, Judge Keating and Criminal Procedure, 36 Brook. L. Rev. 41 (1969).

Rochester History, Vol. XLI, October 1979, No. 4, Rochester’s Congressmen – Part II 1869-1979, edited by Joseph W. Barnes, City Historian – published by Rochester Public Library.

Steme, Joseph R.L., Kennedy in 1964, Clinton in 2000, The Baltimore Sun, October 1, 2000, available on the website of the Institute for Policy Studies, Johns Hopkins University www.jhu.edu/ips/publications/articles/kennedy.html.

White, Mark Jonathan, The Cuban Missile Crisis, Macmillan Press Ltd. (1996).

Published Writings Include:

The Paradoxes of Civil Disobedience, 14 N.Y.L.F. 687 (1968).

A Proposal for the Law Revision Process, 31 Alb. L. Rev. 45 (1967).

My Advance View of the Cuban Crisis, Look Magazine, November 3, 1964, p. 96.

Government of the People, The World Pub. Co., Cleveland, Ohio (1964).

Myth, Reality, and the Future of Antitrust, 24 A.B.A. Antitrust Section 59 (1964).

The Senate Judiciary Committee, 28 Tenn. L. Rev. 7 (1960-1961).

Federal Grant-In-Aid Programs: New York’s Experience, 34 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1011 (1959).

The Law and the Conquest of Space, 25 J. Air L. & Com. 182 (1958).

Proposed Remedial Legislation: Protection for Witnesses in Congressional Investigations, 29 Notre Dame L. Rev. 212 (1953-1954).

Endnotes

- Giannottasio, Gerard., Abstract to: “The Judgeship of Kenneth B. Keating and the Limits of Judicial Reform.” Ph.D. dissertation, State University of New York at Stony Brook, 1994.

- Id. See also, Baade, Hans W., Judge Keating and the Conflict of Laws, 36 Brook. L. Rev. 10 (1969); Pitler, Robert M., Judge Keating and Criminal Procedure, 36 Brook. L. Rev. 41 (1969).

- Congressional Record, 87th Cong., 1st Sess., 12581, quoted in White, The Cuban Missile Crisis, at 93 (1996).

- In Memoriam, 36 N.Y. 2d vii-viii (1975).

- Giannottasio, Gerard., Abstract to: “The Judgeship of Kenneth B. Keating and the Limits of Judicial Reform.” Ph.D. dissertation, State University of New York at Stony Brook, 1994, available at http://wwwlib.umi.com/dissertations/cart?add’9522223.

- Keating, Kenneth B., Book Review, 6 Duquesne U. L. Rev. 327 (1968).

- Liberty National Bank v. Buscaglia, 21 N.Y. 2d 357 (1967).

- McCullough v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819).

- Liberty National Bank v. Buscaglia, 21 N.Y. 2d 357, 371. In a subsequent case, the Supreme Court held that it was unnecessary to reach the issue because Congress had specifically mandated a tax exemption by statutory enactment. First Agricultural Nat’l Bank v. State Tax Commission, 392 U.S. 339 (1968).

- Gallagher v. St. Raymond’s Roman Catholic Church, 21 N.Y. 2d 554 (1968).

- Id. at 558.

- Millington v. Southeastern Elevator Co., 22 N.Y. 2d 498 (1968).

- Id. at 507.

- Keating, Kenneth B., A Proposal for the Law Revision Process, 31 Albany L. Rev. 45, 56 (1967).

- Id.

- Flanagan v. Mount Eden General Hospital, 24 N.Y. 2d 427 (1969).

- Id. at 431.

- Id. at 434-35.

- Walkovszky v. Carlton, 18 N.Y. 2d 414 (1966).

- Id. at 422.

- See e.g., Cary, William L., Corporations – Cases and Materials 97 (4th ed. abridged, Foundation Press, 1970).

- Riss v. City of New York, 22 N.Y. 2d 579 (1968).

- Id. at 583.

- See e.g., Twerski, Aaron D. and Henderson, James A., Torts – Cases and Materials 454 (Aspen Publishers, 2003).

- Pitler, Robert M., Judge Keating and Criminal Procedure, 36 Brook. L. Rev. 41 (1969).

- Narcotic Addiction Control Commission v. James, 22 N.Y. 2d 545 (1968).

- Id. at 552.

- Matter of Gregory W., 19 N.Y. 2d 55 (1966).

- In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1, 46 (1967).

- People v. Katz, 21 N.Y. 2d 132 (1967).

- Id. at 135.

- Brabson v. Wilkins, 19 N.Y. 2d 433 (1967).

- Pitler, Robert M., Judge Keating and Criminal Procedure, 36 Brook. L. Rev. 41, 58 (1969).

- Babcock v. Jackson, 12 NY 2d 473 (1963).

- Dym v. Gordon, 16 N.Y. 2d 120 (1965).

- Macy v. Rozbicki, 18 N.Y. 2d 289, 292 (1966).

- Tooker v. Lopez, 24 N.Y. 2d 569 (1969).

- Dym v. Gordon, 16 N.Y. 2d 120 (1965).

- Baade, Hans W., Judge Keating and the Conflict of Laws, 36 Brook. L. Rev. 10 (1969).

- “Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes in the Congress of the United States of the Life and Contributions of Kenneth B. Keating” Senate Doc. No. 94-74, 94th Cong. 1st Sess. (U.S.G.P.O. Washington: 1975)