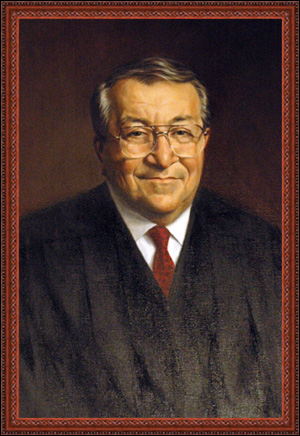

Judge Vito J. Titone was a man of contradictions. He relished traditions, but embraced change. He was always practical in his approach to legal questions, but loved the challenge of the arcane and highly theoretical procedural rules. He was irreverent to the core, but was a great respecter of religious practice. He was widely known as one of the most liberal members of the Court of Appeals during his tenure there, but held conservative views on many issues. He hated footnotes, but could not resist the temptation to sprinkle them liberally throughout his opinions. He was profoundly patriotic, but was privately critical of many specific government policies. And, although he often took novel approaches to the legal questions that were brought to his court, he espoused a philosophy of strict constitutional construction, adherence to stare decisis and judicial restraint. Despite all of these contradictions, however, Judge Titone was remarkably consistent in at least one very important respect – he never took himself or his robes too seriously. It is that trait, along with his irrepressible sense of humor and devotion to his family, that his colleagues and friends will remember long after the force of his judicial opinions has faded.

The Early Years

Although he was rooted in the legal and political establishment of Staten Island, New York, Vito Joseph Titone, Jr. was actually born on July 5, 1929 in Brooklyn and raised in Queens. He often quipped that he had married into Staten Island and that his “foreign” birth doomed him to the permanent status of an outsider in that closely knit community. Nevertheless, he was proud of being a Staten Islander and always displayed the borough’s flag in his chambers along with the United States and New York State flags.

The third child of Vito Joseph Titone, Sr. and Elena Titone, Vito Titone initially thought he would to be an engineer rather than following in his father’s footsteps as a lawyer. However, even as a teenager, he absorbed some of his parents’ values, including their reverence for education. After having brought home a particularly poor high school report card, he was taken to visit the sweatshops where several of his father’s clients worked. Vito was deeply affected by the conditions and grinding effects of poverty that he saw and determined from that point forward to take full advantage of whatever educational opportunities he was offered. After two years of studying engineering at New York University, Titone decided that he wanted to pursue a career in law after all.

Titone’s plans to go to law school were temporarily postponed when he enlisted in the Army a few months after his 1951 graduation from college. Although he was scheduled to go to Korea, Titone was diverted to England where he was assigned the unlikely job of photographer for the Army’s Public Information Office. In his later years, Titone often joked about the “hardships” he had to endure in post-World War II London as a visitor at Queen Elizabeth’s June 1953 coronation and as an escort for then-Governor Earl Warren’s daughter “Honeybear.” Nonetheless, his military experience left him with a long-term interest in cameras and photography-an interest that he passed on to his artistically gifted daughter Elena.

Once he left active military duty, Titone returned to civilian life as a law student at St. John’s University School of Law, which was then located in Brooklyn, New York. He soon made friends with another young Italian-American classmate, Mario Cuomo, who later served three terms as New York State’s Governor and, in fact, appointed Titone to the Court of Appeals. Titone and Cuomo studied together1 and often “double dated” with the two women (Margaret Viola and Matilda Raffa) who would later become their wives. At one point during law school, as Judge Titone told the story, he and Cuomo were called into the dean’s office and told that, despite their obvious talents, they would “never get anywhere” as long as they continued to use their highly ethnic first names. The story may well be apocryphal, but – true or not – it speaks eloquently about the changing American attitudes toward immigrants as well as about the strength of Titone’s identification with his Italian-American heritage. In fact, in one legal analyst’s view, Titone’s heritage would later have a profound influence on his judicial decisions.2

After graduating from law school, Titone worked for about a year for a large New York City law firm, but he soon tired of large-firm practice and opted to open a firm of his own in Manhattan in partnership with Nicholas Maltese. It was not long, however, before Titone turned his attention to local politics. Following a time-honored tradition in local party politics, Titone ran a doomed campaign against the highly popular Staten Islander John J. Marchi3 and was rewarded for his “sacrifice” with a judicial nomination.4 Titone ran for a seat on the State Supreme Court with the backing of the Democratic, Republican, and Conservative Parties. In November 1968, at the age of 39,5 Titone was elected to the Supreme Court bench.

The Supreme Court Years (1969-1975)

Although best known for his writings in the Court of Appeals, Judge Titone achieved a fair amount of notoriety for his work on the trial bench. He presided over the first trial in which the well-known organized crime figure John Gotti was brought to justice.6 He also presided over a lawsuit against the State Office of Mental Hygiene challenging the appalling, and highly publicized, conditions at Willowbrook State School, which was a state-run facility on Staten Island for the developmentally disabled.7

It was during his years on the trial bench that Judge Titone developed a lifelong commitment to drug rehabilitation and alternative sentencing for non-violent offenders with histories of substance abuse. Initially skeptical about residential treatment programs, Judge Titone responded to a “dare” by visiting a new facility on Staten Island called Daytop Village. He was so impressed by what he saw – and so distressed by what he believed was the futility of sentencing young addicts to lengthy prison terms – that he became active in the Daytop organization. As a member of Daytop’s Board of Governors, Titone spoke out against harsh criminal penalties for substance abusers whenever the limits of his judicial role permitted.

The Appellate Division Years

Judge Titone was designated an associate Justice of the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court by Governor Hugh L. Carey in 1975.8 After his swearing in, he was quickly charmed by the traditions of the court, the intellectual prowess of his colleagues and the lovely architecture of the courthouse, which is nestled on a tree-lined side street in Brooklyn Heights. During his tenure at the Appellate Division, Second Department, Judge Titone continued his habit of reaching out to the courthouse staff at all levels, cajoling, joking, and demonstrating his genuine interest in their lives.

While he sat on the Appellate Division, Judge Titone wrote over 150 opinions. Many of these involved the bread-and-butter civil and criminal issues that are routinely brought to the intermediate appellate courts. Within his substantial body of Appellate Division writings, however, is an assortment of opinions of lasting significance. In Howard v. Lecher,9 for example, Judge Titone wrote a carefully reasoned opinion rejecting a novel claim for emotional harm arising from the supposed “wrongful birth” of a child born with Tay-Sachs disease. In L-town Limited Partnership v. Sire Plan, Inc.,10 Judge Titone drew on the experience of other jurisdictions, as well as legal history in New York, and wrote an exhaustive review of the issue monetary sanctions against parties for frivolous and vexatious litigation. Although the Court of Appeals ultimately disagreed with his conclusion that the State’s courts have inherent authority to impose such sanctions,11 Judge Titone’s L-Town opinion was influential in bringing attention to the need for sanctions against attorneys and litigants who abuse the judicial system.12

Judge Titone also had a mischievous side that occasionally came out in his writings. His dissenting opinion in People v. Briggins13 is an example. In Briggins, Judge Titone protested his colleagues’ acceptance of local jury-selection procedures that he deemed racially exclusionary. After discussing the governing constitutional precepts, Judge Titone ended his opinion with a jab at government officials, who reportedly were willing to spend $600,000 to improve an airport runway to accommodate an air cargo company that wanted to fly out pregnant cows, but were unwilling to spend the relatively small sums necessary to transport poor prospective jurors to the courthouse. Aside from the slightly rebellious sense of humor reflected in these remarks, Judge Titone’s Briggins dissent highlights a more fundamental personal trait – his populist sensibility. Whether or not his judicial philosophy was always consistent, Judge Titone demonstrated through his writings, as well as through his nonjudicial activities, his affinity and concern for society’s neglected and disadvantaged.

Judge Titone’s lingering regret over one case he sat on in the Appellate Division, People v. Harris,14 is illustrative of another personal trait: his humanity. Harris involved a celebrated murder trial in which a woman who had conducted a long-term relationship with a well-known author/doctor killed him after learning that he was deserting her for a younger woman. Years after the woman was convicted of second-degree murder and sent to prison to serve a 15-year to life sentence, Judge Titone was haunted by the case, especially the fact that her lawyer had opted to forego a plea bargain that would have left his client convicted of the more appropriate crime of manslaughter. His sympathy for the defendant was reflected in an interview in which he told the interviewer that he regarded her as a victim of psychological abuse.15

The Court of Appeals Years (1985-1998)

In 1985, Vito J. Titone was appointed to a seat on the Court of Appeals by his long-term friend, then-Governor Mario M. Cuomo. As he told the story, the Governor called Judge Titone’s home and demanded to speak to Margaret, his wife, asking her whether she wanted “to get rid of him by sending him to Albany.” She assented, thereby paving the way for her husband to become the first Staten Islander ever to sit on the Court of Appeals.

During the thirteen years he sat on the Court of Appeals bench, Judge Titone developed a reputation as the most “liberal” member of the Court. Not surprisingly, the truth is more complex. One of Judge Titone’s earliest Court of Appeals opinions was SHAD Alliance v. Smith Haven Mall,16 in which he declined to extend the New York State constitutional guarantees of free speech to a privately owned shopping mall, despite arguments from his colleagues that shopping malls had become the new “town squares.”17 In a statement that reflected one important strand of his judicial philosophy, Judge Titone wrote in SHAD Alliance: “A disciplined perception of the proper role of the judiciary, and more specifically, discernment of the reach of the mandates of our State Constitution, precludes us from casting aside so fundamental a concept as State action in an effort to achieve . . . a more socially desirable result.”18 The same “conservative” judicial perspective was later expressed in a law review article in which Judge Titone argued for an approach to State constitutional law that focuses on the “state’s idiosyncratic history and traditions” and its “rich body of common law.”19 Judge Titone’s insistence on a methodology of state constitutional analysis firmly rooted in either the text of the State Constitution or the specific history and culture of the State is all the more remarkable because he wrote at the tail end of an era when the Court of Appeals and other state high courts were taking an expansive view of State Constitutions, in part in reaction to a United States Supreme Court that was increasingly hostile to individual rights.20

On the other hand, Judge Titone was notable for the “liberal” or pro-defense position he took in cases involving criminal defendants’ rights.21 In one of the clearest statement of his views on the Fourth Amendment, for example, Judge Titone wrote in People v. Keta:22 “Our responsibility in the judicial branch is not to respond to these temporary crises or to shape the law to as to advance the goals of law enforcement, but rather to stand as a fixed citadel for constitutional rights, safeguarding them against those who would dismantle our system of ordered liberty in favor of a system of well-kept order alone.”

Judge Titone wrote these words at a time when the State judiciary was under attack by certain politicians for “coddling criminals.” In fact, his concern about the political attacks on the judiciary and the concomitant threat to judicial independence prompted him to write bitterly in a 1996 law review article that “the kind of criticism that exploits fear and prejudice rather than educates is a particularly cynical and cowardly form of demagoguery because its targets, the judges who wrote or voted for the challenged decisions, operate under a strict code of ethics and custom that prevents them from responding.”23

His passionate belief in judicial independence also led him to write a separate dissenting opinion in a judicial misconduct case involving a jurist who had been the subject of a firestorm of sensational newspaper attention and attacks by politicians for a bail decision he had made.24 While conceding that the jurist’s conduct in other matters had been less than exemplary, Judge Titone nevertheless dissented from the majority’s decision to remove him from the bench, arguing that the removal decision “has sent a message that the State’s judicial disciplinary procedures are susceptible to manipulation by public officials” and thereby “str[uck] at the heart of the notion of judicial independence which is so critical to our tripartite system of government.”25

Judge Titone’s fundamental populist spirit also played a role in his so-called “liberal” approach to criminal cases. For example, his ever-present concern for the underdog led him to dissent in a highly publicized murder case in which a youthful suspect had been isolated and prevented from consulting with an attorney friend until after he confessed.26 Judge Titone said privately that his solicitude for criminal suspects was motivated, in part, by a measure of skepticism toward officialdom that he acquired during his tenure on the trial bench.

In addition to his writings in the field of criminal law, Judge Titone is noted for his groundbreaking opinions in the area of family law. Perhaps his most widely known opinion is Braschi v. Stahl Assocs. Co.,27 in which he held that nontraditional households, including gay partnerships, could be considered “families” where they share such critical characteristics of traditional families as lifetime emotional and financial commitment and interdependence. Another seminal writing was his opinion in Tropea v. Tropea,28 which involved the conflicting claims of divorced parents that often arise when the custodial parent wishes to move to a distant locale. In an approach that reflected his concern for the powerless, Judge Titone refused to consider the case solely from the perspective of the clashing interests of the parents. Instead, he wrote that the rights and needs of the children in these situations should control because they are the “innocent victims of their parents’ decision to divorce and are least equipped to handle the stresses of the changing family situation.”29

Judge Titone’s body of majority and dissenting opinions is too vast and diverse to lend itself to easy categorization.30 Like the man himself, Judge Titone’s Court of Appeals writings are not always ideologically or jurisprudentially consistent, nor do they fit comfortably at any one spot in the political spectrum. In the end, what can be said about Judge Titone’s body of work is that is reflects a person who was committed to sound legal reasoning, deeply respectful of law, precedent and tradition and, most importantly, cared about the people who rely on the legal system to order their lives.

No discussion of Judge Titone’s years on the Court of Appeals would be complete without reference to the impact his irrepressible personality had on this colleagues. While he did not shy away from the conflicts that necessarily accompany the process of deciding difficult cases, he was also quick with a joke or a story and often worked hard to defuse tensions. His sense of humor took some getting used to, but most of his colleagues and the Court staff were won over in the end. Judge Titone’s smile, which was wide enough to engrave deep creases in his cheeks, was almost impossible to resist.

Over the 13 years he sat on the Court of Appeals, Judge Titone developed warm friendships with many of his colleagues and was particularly close to Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye and Associate Judge Howard A. Levine. His friendships, however, were not limited to his colleagues on the bench. Judge Titone was not happy unless he had reached out to the Court’s legal and non-legal staff and learned everything he could about their families and ambitions. Like the other Judges, Judge Titone worked late into the night when the Court was in session in Albany. However, even after working on his cases until close to midnight, Judge Titone could often be seen unwinding with a group of young law clerks in the lounge of the Albany hotel where he stayed. Many of the law clerks who worked at the Court during his tenure have fond memories of swapping stories and telling jokes with him late into the night.31

Judge Titone never turned down a request from a staff member for advice or help. In fact, his genuine interest in the people who made the courthouse run was reflected in the efforts he made to help several of them go back to school or advance their careers. As a result of his expansive manner and generosity of spirit, Judge Titone even made friends with the staff of the Albany hotel that was home to many of the Judges and their staff while they were in town. In fact, the Chief Judge occasionally quipped that if she wanted a better room or special favor at the hotel, she had to go through Judge Titone.

The stories about Judge Titone’s humor and kindness abound. Although he was a diabetic, Judge Titone loved to ply his colleagues with sweets. One often-told story involves the collegial restaurant dinners that the Judges enjoyed while they were in Albany. Judge Titone would periodically tell the waiter that it was the Chief Judge’s birthday, with the result that the group would be treated to a special desert. Chief Judge Kaye once estimated that she had “likely had fifty or more bogus birthdays” in the 13 years she sat with Judge Titone.32 A less known but equally tasty custom was Judge Titone’s annual celebration of St. Joseph’s Day (the Italian festival that occurs on March 19th) by delivering a huge tray full of Italian pastries to his colleagues’ Chambers or to the “Red Room” at the Courthouse.33 Although many of the Judges complained about the caloric content of the cannolis and zeppoles, few declined to sample the sugary treats.

As those who served with him will remember, Judge Titone’s presence was felt everywhere in the Courthouse. In the end, it was because of his gift for laughter and for making friends that Judge Titone’s announcement of an early retirement was met with such universal sadness and a sense of profound loss.34 One commentator who had worked with him on the Court described his personal impact in this way:

[T]o so many who know him or have worked with him, both inside and outside the Court of Appeals, Vito Titone has been their ‘favorite judge.’ . . . Judge Titone is a friend. He has been loyal, generous, protective, unwavering, and just plain gutsy for so many who have needed a helping hand, or an ally, or some guidance or support.35

Judge Titone loved the Court of Appeals and all of its inhabitants – and the affection was certainly returned.

The Retirement Years (1998-2005)

After leaving his black robes behind, Judge Titone took a position “of counsel” to Mintz & Gold, LLP, a law firm in New York City. In addition, he served as a mediator and arbitrator.

Judge Titone’s retirement enabled him to spend time with the people who mattered to him the most: his wife, children, and grandchildren. He traveled frequently to England, where one of his daughters resides with her husband and children.

Although his health was slowly deteriorating, Judge Titone remained active, practicing law, enjoying friendships with old friends and engaging in his favorite outdoor pastime, golf. Assisted by his longtime secretary, Florence Azzara, Judge Titone continued to hold his annual “Titone’s Tigers” parties, which began as vehicles for bringing fledgling law clerks together with judges in a congenial setting and morphed into large catered events that drew dozens of old and new friends together.

Judge Titone died on July 6, 2005, the day after his 76th birthday. Fittingly, his last days were spent surrounded by his family, his lifelong friends from Staten Island and his admiring friends from his days at the Court of Appeals. Those who were there with him on his birthday were saddened by his rapidly sinking condition. However, those who lingered to the end had the pleasure of seeing him take his last meal, which ended with a bite of a cannoli. That is how Judge Titone himself would have liked to be remembered.

In the final analysis, Judge Titone’s good friend, Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye, penned the most fitting final memoriam. As she tells the story, one member of the State Bar Committee on the Judiciary was fond of asking prospective judges how they would write their own epitaphs. When Judge Titone came before the Committee as a candidate for appointment to the Court of Appeals, he responded to the question without hesitation: “Always he did his best to be a good and fair judge.”36 Those who knew him and those who will read his judicial writings in the future will certainly agree that he achieved his goal.

Progeny

Judge Vito Joseph Titone (1929-2005) is survived by his wife, Margaret Viola Titone, who stood by him through all of the good and bad times in his personal life and judicial career. He is also survived by two sisters: Jeanette Titone Busceme and Marie Ann Titone Izzo.

Vito and Margaret Titone were married on December 30, 1956. They had four children: Steven Titone (born May 28, 1958), Elena Titone Hill (born January 24, 1961), Matthew Titone (born January 24, 1961) and Elizabeth Titone Alderson (born July 31, 1968). Elena and her husband Philip Hill live in England and have three children: Callum Elizabeth Hill (born April 15, 1987), Liam John Hill (born May 16, 1990) and Kiera Alice Hill (born April 14, 1993). Elizabeth and her husband Russell Rogers Alderson live in Brooklyn, New York and have two children: Zachary Titone Alderson (born February 23, 1999) and Henry Rogers Alderson (born July 9, 2000).

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Bonventre, Dedication, 61 Alb. L. Rev. 1395, 1396 (1998).

Kaye, Dedication: A Tribute to Law and Humanity: Judge Vito J. Titone, 61 Alb. L. Rev. 1391, 1392 (1998).

Lauricella, The Italian-American Experience and Its Influence on the Judicial Philosophies of Justice Antonin Scalia, Judge Joseph Bellacosa and Judge Vito Titone, 60 Alb. L. Rev. 1701 (1997).

Pines, “Judge Vito Titone: The Liberal from Staten Island,” Upstate Record, October 12, 1992.

Published Writings Include:

First, Do No Harm, New York Law Journal, February 1, 2001, p. 2.

The Judiciary as Political Stepping-Stone: The Case for More Temperate Debate, 12 St. John’s J. Legal Commentary 33, 38 (1996).

State Constitutional Interpretation: The Search for an Anchor in a Rough Sea, 61 St. John’s L. Rev. 431, 463 (1987).

Endnotes

- According to Judge Titone, neither he nor Former Governor Cuomo would have succeeded in their real property class if it had not been for the advice and assistance of Vito Titone Sr., who was then in charge of the State Attorney General’s Real Property Bureau.

- P. A. Lauricella, The Italian-American Experience and Its Influence on the Judicial Philosophies of Justice Antonin Scalia, Judge Joseph Bellacosa and Judge Vito Titone, 60 Alb. L. Rev. 1701 (1997).

- Born in 1921, John J. Marchi was first elected to the New York State Senate in 1957. He was still serving in that capacity in 2006.

- Titone’s primary campaign stance was his opposition to the recently introduced notion of a State sales tax. His position, which he later acknowledged was futile, was partially successful in that it drew attention to the campaign of a young and relatively unknown politician.

- At the time of his election, Titone was the youngest person ever to have attained a seat on the Supreme Court.

- Judge Titone told one reporter that Roy Cohn, who represented Gotti, complained about the jail food that his client was being forced to eat and demanded that he be permitted to bring in his own food and cigarettes from outside. Titone acceded, but only on condition that the Gotti contingent bring enough food and cigarettes for all of the inmates. As Judge Titone explained it, he “couldn’t have the [rest of the inmates] eating baloney while [Gotti] was dining on fancy Italian food.” Titone also insisted that any cigarettes brought into the jail from outside have legitimate tax stamps. In the end, according to Titone, the inmates were enjoying the Gotti bounty so much that they were refusing to accept plea bargains. P. Pines, “Judge Vito Titone: The Liberal from Staten Island,” Upstate Record, October 12, 1992, p. 5. The story is especially interesting because it highlights three of Titone’s most enduring character traits: his mischievous, slightly subversive sense of humor, his sensitivity to ordinary people, and his ultimate regard for the law.

- See Renelli v. Department of Mental Hygiene, 73 Misc. 2d 261 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Richmond Co. 1973). Judge Titone was deeply moved by the level of patient neglect demonstrated by the evidence. He stated: “It is a sorry state of affairs when those charged with the care of people like [the plaintiff] must be forced by a Court of law to fulfill their obligations, but apparently nothing less will produce results.” Id. at 266. In a highly unusual passage from his opinion, Judge Titone also expressed his appreciation of the members of the press who had been instrumental in exposing the conditions at Willowbrook to the public. “In this instance,” he stated, “the Fourth Estate functioned in the finest traditions of a free press.” Id. at 265.

- Judge Titone was re-designated by Governor Mario M. Cuomo in 1983.

- 53 A.D.2d 420 (2nd Dept. 1976), aff’d 42 N.Y.2d 109 (1977).

- 108 A.D.2d 435 (2nd Dept. 1985), modified, 69 N.Y.2d 670 (1986).

- A.G. Ship Maintenance Corp. v. Lezak, 69 N.Y.2d 1(1986).

- Following the Court of Appeals’s decision in L-Town and A.G. Ship Maintenance Corp. v. Lezak, 69 N.Y.2d 1(1986), a system for imposing sanctions was incorporated in the Rules of the Chief Administrator. See 22 N.Y.C.R.R. ‘ 130-1.1.

- 67 A.D.2d 1004, 1005 (2nd Dept. 1979), rev’d 50 N.Y.2d 302 (1980).

- 84 A.D.2d 63 (2nd Dept. 1981), aff’d 57 N.Y.2d 335 (1982), cert. denied 460 U.S. 1047 (1983).

- P. Pines, “Judge Vito Titone: The Liberal from Staten Island,” op. cit., p. 5.

- 66 N.Y.2d 496 (1985).

- 66 N.Y.2d at 512-513 (Wachtler, Ch. J., dissenting). In an earlier decision, the United States Supreme Court had ruled that the free speech guarantee in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution does not extend to privately owned shopping malls. PruneYard Shopping Center v. Robins, 447 U.S. 74 (1980). Chief Judge Sol Wachtler, and to a lesser extent Associate Judge Matthew Jasen, argued that a different analysis should be applied under the New York State Constitution. Writing for a five-Judge majority, however, Judge Titone argued that there was no historical or contextual basis for extending the New York State Constitutional provision, N.Y. Const., Art. I, ‘ 8, beyond the limits of its federal equivalent.

- 66 N.Y.2d at 505.

- Hon. Vito J. Titone, State Constitutional Interpretation: The Search for an Anchor in a Rough Sea, 61 St. John’s L. Rev. 431, 463 (1987). This position also informed Judge Titone’s concurrence in Immuno AG. v. J. Moor-Jankowski, 77 N.Y.2d 235, 263, (1991) (Titone, J., concurring), vacated 497 U.S. 1021 (1990).

- E.g., People ex rel. Arcara v. Cloud Books, 68 N.Y.2d 553 (1985), rev’d 478 U.S. 97 (1986); People v. Bethea, 67 N.Y.2d 364, 493 N.E.2d 937, 502 N.Y.S.2d 713 (1986); Sharrock v. Dell Buick-Cadillac, 45 N.Y.2d 152 (1978); People v. Hobson, 39 N.Y.2d 379 (1976); see W. Brennan, State Constitutions and the Protection of Individual Rights, 90 Harv. L. Rev. 489 (1977).

- See, e.g., People v. Jackson, 78 N.Y.2d 638, 651 (1991) (Titone, J., dissenting); People v. O’Rama, 78 N.Y.2d 270 (1991); People v. Duuvon, 77 N.Y.2d 541, 546 (1991) (Titone, J., concurring); People v. Dunn, 77 N.Y.2d 19 (1990), cert. denied 401 U.S. 1219 (1991); People v. Torres, 74 N.Y.2d 224 (1989).

- 79 N.Y.2d 474 (1992).

- Vito J. Titone, The Judiciary as Political Stepping-Stone: The Case for More Temperate Debate, 12 St. John’s J. Legal Commentary 33, 38 (1996).

- Matter of Duckman, 92 N.Y.2d 141, 156 (Titone, J. dissenting).

- Id.; see also Johnson v. Pataki, 91 N.Y.2d 214, 228 (1997) (Titone, J., dissenting) (taking issue with Governor’s decision to substitute State Attorney General for Bronx County District Attorney in criminal prosecution solely because of disagreement concerning use of death penalty). Parenthetically, Judge Titone privately expressed relief that he had not had not been called upon to decide a death-penalty appeal while he was on the Court of Appeals bench. He was personally opposed to the death penalty and was concerned that his strongly-held views on the subject would make it difficult to be objective about the legal issues. Nevertheless, he made it clear that he would not have shirked his responsibility to evaluate a death penalty case using the same methods and principles as he would apply to any other case.

- People v. Salaam, 83 N.Y.2d 51, 58 (1993) (Titone, J., dissenting). Judge Titone was particularly gratified when the defendant in Salaam was subsequently exonerated after another malefactor confessed to the crime.

- 74 N.Y.2d 201 (1989).

- 87 N.Y.2d 727 (1996).

- 87 N.Y.2d at 580.

- For a more detailed review of Judge Titone’s Court of Appeals writings, see L. Harrison, Dedication to the Honorable Vito J. Titone, 14 Touro L. Rev. 569 (1998).

- Judge Titone had especially warm relationships with his own law clerks. Lisabeth Harrison was with him for 12 of his 13 years on the Court of Appeals. Lisa Colosi Florio was also with him for a substantial portion of his Court of Appeals tenure. His other law clerks were Loren Selznick, Alex Sokolov, Steven G. Mintz, and James Scotti. Florence Azzara, who had worked with him at the Appellate Division, was his secretary and friend during his entire 13-year term on the Court of Appeals.

- Hon. Judith S. Kaye, Dedication: A Tribute to Law and Humanity: Judge Vito J. Titone, 61 Alb. L. Rev. 1391, 1392 (1998).

- The “Red Room,” named after the color of the room’s carpet, was the first-floor room in the courthouse where the Judges would meet informally after oral argument to draw lots for the cases.

- Judge Titone could have remained on the Court until the end of 1999, the year he turned 70. However, he elected to resign his position at the end of the Court’s 1997-1998 session.

- Vincent Martin Bonventre, Dedication, 61 Alb. L. Rev. 1395, 1396 (1998).

- Hon. Judith S. Kaye, Dedication: A Tribute to Law and Humanity: Judge Vito J. Titone, op. cit., p. 1392.