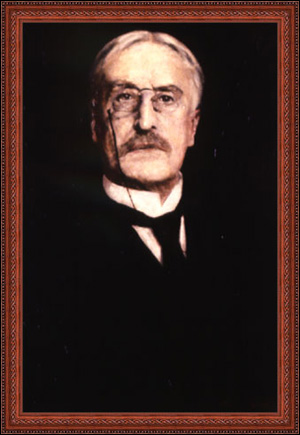

A man of many interests “from teaching medical jurisprudence to writing literary reviews for a popular New York newspaper” Judge Willard Bartlett brought a diverse intellect to the New York Court of Appeals. Judge Bartlett’s literary background served him well in his judicial career. Upon his death in 1925, the Court remarked that his “clear, forceful and yet gracious literary style . . . is due in part without doubt to his great love for books and general literature, and to his occasional literary reviews and criticisms published in the daily press.” With his extensive legal and life experience, Judge Bartlett presided over some of New York’s most important early 20th Century cases.

Early Life

Willard Bartlett was born in Uxbridge, Massachusetts on October 14, 1846, the eldest son of Agnes Willard and William O. Bartlett. His father, a prominent New York lawyer, served as defense counsel to the infamous William “Boss” Tweed. Agnes Willard was the granddaughter of Dr. Samuel Willard, who represented Worcester County at the Massachusetts convention in 1788 to determine whether to ratify the United States Constitution. Willard Bartlett had one younger brother, Franklin Bartlett, who rose to the rank of Colonel in the military. Franklin also was a prominent attorney and served as a representative from New York to the 53rd and 54th United States Congresses.

In 1857, the Bartlett family moved to Suffolk County on New York’s Long Island where William O. Bartlett had purchased a 1,000-acre farm. A history of the property notes that William O. Bartlett “became legendary for building a spur from the railroad, which extended onto his estate. He kept his workers busy by having them build several stone walls on his estate.”

Willard Bartlett was a graduate of Polytechnic Institute in Brooklyn and Columbia College in New York. One year before his graduation from Columbia in 1869, Bartlett was admitted to the New York Bar. He married Mary Fairbanks Buffum on October 26, 1870 in Brooklyn, and the couple had two daughters, Maud and Agnes.

Although he concentrated on his legal studies, Bartlett earnestly pursued his literary interests. While at Columbia College, he was a member of the Philolexian Society, which was established by associates of Alexander Hamilton in 1802 to improve the “oratory, composition and forensic discussion” of its members. Bartlett also wrote literary reviews for the New York Sun, a popular newspaper that published the famous editorial “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus” in 1897. The paper also published a series of articles in 1835, claiming that the Moon harbored life. The fictitious articles became known as the “Great Moon Hoax.” In his capacity as a literary critic for the Sun, Bartlett’s apparent last review was of Frank M. O’Brien’s book, “The Story of the Sun,” which detailed the Great Moon Hoax. Bartlett’s brother, Franklin, served as counsel to the New York Sun. Both Willard and Franklin apparently developed a close friendship with Charles A. Dana, the newspaper’s controversial owner. Employing his literary background, Willard Bartlett helped Dana revise the American CyclopaediaCa late-19th Century “dictionary of general knowledge.”

Legal Career

After graduating from Columbia College, Bartlett started his legal career in association with Elihu Root, the esteemed jurist who later served as a United States Senator and as Secretary of War for President Theodore Roosevelt. Root also won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1912. Bartlett practiced with Root from 1869 to 1883. Both Root and Bartlett, among others, served with William O. Bartlett as defense counsel to William “Boss” Tweed. Prior to Tweed’s trial, the defense attorneys petitioned presiding judge Noah Davis to recuse himself from the case on the ground of his bias against Tweed. After he sentenced Tweed, Judge Davis held several of the defense attorneys, including Elihu Root and Willard Bartlett, guilty of contempt for bringing the petition. The defense attorneys, however, were not subjected to disciplinary proceedings. Specifically, Judge Davis relieved Elihu Root and Willard Bartlett from any penalties “on the ground of youth and domination by their seniors.”

In 1883, apparently not worse for wear after the Tweed trial, Bartlett was elected as a justice at the New York Supreme Court in Kings County and once again in 1897. He presided over the trial of John Y. McKane, the so-called “Czar of Coney Island.” Among other things, McKane and his cohorts allegedly intimidated voters at polling booths and submitted names of deceased persons for the voting tally. Accordingly, McKane was charged with conspiracy to commit voting fraud. Judge Bartlett held that, despite a growing trend among other states to hold to the contrary, in “the case of an executed conspiracy to commit a felony the conspiracy, which is a misdemeanor, merges in the felony” (People v. McKane, 7 Misc. 478, 479 [1894]).

While on the bench, Judge Bartlett impressed his peers. The following passage indicates the esteem in which he was held: “His learning in the law was deep and profound and he had that qualification born in him and not acquired which is really necessary for the making of a great jurist, a natural instinct for law and for justice.” Judge Bartlett’s judicial style was described as “methodical and prompt; in speech he is deliberate but not slow; on the bench he is precise without being tedious, expository but not obtrusive.” Held in such high regard, upon the creation of the Appellate Division in 1896, Judge Bartlett, along with Charles F. Brown, Calvin E. Pratt, Edgar M. Cullen and Edward W. Hatch, was assigned to that court for the Second Department.

During his time on the bench, Judge Bartlett also pursued his interest in the medical field. In 1898, Judge Bartlett began teaching medical jurisprudence at the Long Island College Hospital. In a paper that he read before the New York State Medical Association, Judge Bartlett addressed concerns regarding medical expert evidence. Hoping to improve the quality of such evidence, he wrote:

I should be sorry to feel that the prospect of reform was hopeless. There is one direction in which it seems to me brighter than any other. You have a code of medical ethics which every physician and surgeon is bound in all professional honor to observe. By that code you regulate your own conduct in the practice of medicine, and insist that those who join the ranks of your profession from year to year shall agree to regulate theirs. No statute could practically be more binding. Why may you not extend its provisions so as to embrace the conduct of the medical man when he assumes the role of expert witness?

Despite his frequent forays into the medical and literary fields, Judge Bartlett did not lose focus of his judicial duties. In 1906, Governor Frank W. Higgins named Judge Bartlett to the Court of Appeals. Upon Judge Dennis O’Brien‘s retirement in 1907, Judge Bartlett was elected to the Court. In 1914, he became Chief Judge, succeeding his lifelong friend Edgar M. Cullen. In an address to the New York Bar Association, Judge Bartlett provided a detailed glimpse into a typical Monday for a Court of Appeals Judge in the early 1900s:

Monday, 7:30 a.m. By coupe to Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan. 8:30 a.m., by Empire Express to Albany and there to room at the Ten Eyck. About 1 p.m. luncheon, and thereafter to the Court of Appeals rooms, where the Judges put on their gowns and go into court at 2 o’clock. Listen to the argument of causes from 2 p.m. until 6 p.m., when court adjourns. 6 to 7 p.m. walk an hour or so for exercise or go home and take a nap before dinner, according to weather and inclination. Between 7 and 8 dinner. After dinner, study the cases of the day, the records having been brought to the Judges’ room by the court messenger. Give special attention to the case assigned to you, so as to be ready if possible to report thereon at the consultation on Tuesday. Between 10 p.m. and 12 midnight go to bed.

Throughout his legal career, Judge Bartlett remained mindful of the lawyer’s important role in society and the need to maintain one’s integrity in the legal profession. In his Albany Law School commencement address in 1907, Judge Bartlett, quoting United States Supreme Court Justice John M. Harlan, stated that “‘an advocate . . . owes a duty to the court of which he is an officer and to the community of which he is a member. Above all, he owes a duty to his own conscience.’ The fulfillment of that duty is the sum and substance of the ethical obligation of counsel.” Judge Bartlett served with distinction as Chief Judge until 1916 when he reached the age limit for judicial service under the New York Constitution.

Famous Decisions

In 1906, the Court of Appeals was presented with the issue of whether impossibility could be a defense to the charge of attempting to commit a crime. In People v. Jaffe (185 NY 497), the defendant, Samuel Jaffe, attempted to purchase 20 yards of cloth, which he believed to be stolen material. The cloth, however, had been returned to the rightful owner at the time of Jaffe’s attempted purchase. Jaffe, nevertheless, was convicted of an attempt to receive stolen property, and the Appellate Division affirmed his conviction. Jaffe appealed to the Court of Appeals, which reversed the conviction. Writing for the Court, Judge Bartlett reasoned:

The purchase, therefore, if it had been completely effected, could not constitute the crime of receiving stolen property, knowing it to be stolen, since there could be no such thing as knowledge on the part of the defendant of a non-existent fact, although there might be a belief on his part that the fact existed. . . .

. . . A particular belief cannot make that a crime which is not so in the absence of such belief. Take, for example, the case of a young man who attempts to vote, and succeeds in casting his vote under the belief that he is but twenty years of age when he is in fact over twenty-one and a qualified voter. His intent to commit a crime, and his belief that he was committing a crime, would not make him guilty of any offense under these circumstances, although the moral turpitude of the transaction on his part would be just as great as it would if he were in fact under age. So, also, in the case of a prosecution under the statute of this state, which makes it rape in the second degree for a man to perpetrate an act of sexual intercourse with a female not his wife under the age of eighteen years. There could be no conviction if it was established upon the trial that the female was in fact over the age of eighteen years, although the defendant believed her to be younger and intended to commit the crime

(id. at 500-502). The decision was superseded by the 1967 Penal Law, removing impossibility as a defense to the charge of an attempted crime (see People v. Leichtweis, 59 AD2d 383 [1977]).

Judge Bartlett issued the lone dissent in the seminal products liability case, McPherson v. Buick Motor Co. (217 NY 382 [1916]). In McPherson, the defendant car manufacturer sold an automobile to a retail dealer that, in turn, sold the car to the plaintiff-purchaser. While the plaintiff was driving the car, it collapsed and the plaintiff was subsequently injured. One of the car’s wheels was made of defective wood, and its spokes crumbled into fragments. The defendant manufacturer had purchased the wheel from another manufacturer. The plaintiff sued the defendant manufacturer for negligence. The issue presented in the case was whether the defendant manufacturer owed a duty of care to anyone other than the immediate purchaser, in this case, the retail dealer. The Court affirmed the determination of the courts below that the defendant manufacturer was not absolved from a duty of inspection simply because it had purchased the wheel from a reputable manufacturer. The Court famously held, “[t]here is nothing anomalous in a rule which imposes upon A, who has contracted with B, a duty to C and D and others according as he knows or does not know that the subject-matter of the contract is intended for their use” (id. at 393).

In his dissent, Judge Bartlett argued that well-established case law demanded a different result. He reasoned:

I do not see how we can uphold the judgment in the present case without overruling what has been so often said by this court and other courts of like authority in reference to the absence of any liability for negligence on the part of the original vendor of an ordinary carriage to any one except his immediate vendee. The absence of such liability was the very point actually decided in the English case of Winterbottom v. Wright, and the illustration quoted from the opinion of Chief Judge Ruggles in Thomas v. Winchester assumes that the law on the subject was so plain that the statement would be accepted almost as a matter of course. In the case at a bar the defective wheel on an automobile moving only eight miles an hour was not any more dangerous to the occupants of the car than a similarly defective wheel would be to the occupants of a carriage drawn by a horse at the same speed; and yet unless the courts have been all wrong on this question up to the present time there would be no liability to strangers to the original sale in the case of the horse-drawn carriage” (id. at 399-400 [citations omitted]).

Post-Bench

After retiring as Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals in 1916, Judge Bartlett rejoined Elihu Root in the practice of law. Judge Bartlett also served as an official referee in State cases. On October 26, 1920, he and his wife Agnes celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary with a reception at their home.

Judge Bartlett died on January 17, 1925 at his residence in Brooklyn. He had been suffering from heart disease that had been aggravated by a cold. Services for Judge Bartlett took place at the Unitarian Church of the Saviour in Brooklyn, and the church was filled despite a snow storm, according to a report in the New York Times. Among the honorary pallbearers were Elihu Root, former Governor Nathan L. Miller, then-Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals Frank H. Hiscock and then-Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals Benjamin N. Cardozo. After the services, Judge Bartlett was interred at Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Judge Bartlett was considered a man of great dignity who valued his role on the judiciary. In remembrance, the Court noted that the, “office to him was one of the most important in the gift of the people through which to serve his State and Nation. The judiciary to him was a sacred calling to which he consecrated his life, forgetful of personal gain or of the monetary rewards which might have been his at the bar . . . Such a life was an inspiration.”

Progeny

Judge Bartlett had two daughters, Agnes and Maud, neither of whom had children. Judge Bartlett’s niece, Bertha King Bartlett Benkard, gave birth to a son, Franklin Bartlett Benkard, who married Laura Derby Dupee. Their son James Willard Bartlett Benkard served as a law clerk to Court of Appeals Judge Charles Breitel and is a partner at Davis Polk & Wardwell.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Bartlett, Willard. Legal Ethics: An Address Delivered at Commencement Exercises of Albany Law School in the Hubbard Course on Legal Ethics (June 4, 1907).

Bartlett, Willard. Medical Expert EvidenceCThe Obstacles to Radical Change in the Present System, A Paper Read Before the Association, at the Academy of Medicine, in the City of New York, on October 24, 1899.

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/ (accessed on January 12, 2006).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CharlesAndersonDana (accessed on January 13, 2006).

http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/lpop/etext/tweed/tweed.htm (accessed January 18, 2006).

http://www.biblio.com/books/25630899.html (accessed on January 12, 2006).

http://www.jacksonsweb.org/benkarddescendant.htm (accessed January 19, 2006).

http://www.longwood.k12.ny.us/history/midisl/bartlet.htm (accessed on January 13, 2006).

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/coney/peopleevents/pande03.html (accessed on January 18, 2006).

http://www.philolexian.com/society.shtml (accessed on January 13, 2006).

In Memoriam, 239 NY 642.

In re Isserman, 345 U.S. 286, 293 (1953).

Lectures on Legal Topics, 1921-1922 (New York 1926).

The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Volume XV (1916), at 412-413.

New York Times, January 18, 1925.

New York Times, Obituary Section, January 21, 1925, p. 21.

Published Writings include:

Beyond his judicial decisions, Judge Bartlett wrote various literary and dramatic reviews for the New York Sun.

Endnotes

- In Memoriam, 239 NY 642.

- Willard Bartlett joined with his father and, among others, Elihu Root in petitioning Judge Noah Davis to recuse himself from the case (see http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/lpop/etext/tweed/tweed.htm).

- In this history of the Bartlett property, Nicole Gudz notes that Judge Willard Bartlett later assumed ownership of the land and that a pond near the property became known as Bartlett Pond. According to the history, all three houses on the property were “mysteriously” burned in 1965 and the land is now being used as a golf course (see http://www.longwood.k12.ny.us/history/midisl/bartlet.htm).

- http://www.philolexian.com/society.shtml.

- New York Times, January 18, 1925 (noting that “[p]robably the last writing by Judge Bartlett for The Sun was published in December, 1918Ca review of Frank M. O’Brien’s book, ‘The Story of The Sun.'”).

- Under Dana’s control, the New York Sun heavily backed Ulysses S. Grant for President, but then sharply criticized the administration. The Sun then backed Horace Greeley for President in the next election (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CharlesAndersonDana).

- http://www.biblio.com/books/25630899.html.

- http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=R000430.

- See In re Isserman, 345 U.S. 286, 293 (1953).

- http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/coney/peopleevents/pande03.html.

- In Memoriam, 239 NY 642.

- The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Volume XV (1916), at 412-413.

- Judge Cullen (1843-1922) later served on the Court of Appeals from 1900 to 1904 and as Chief Judge from to 1904 to 1913.

- Bartlett, Willard. Medical Expert Evidence – The Obstacles to Radical Change in the Present System, A Paper Read Before the Association, at the Academy of Medicine, in the City of New York, on October 24, 1899.

- Edgar M. Cullen was a fellow member of the Philolexian Society.

- Lectures on Legal Topics, 1921-1922 (New York 1926).

- Bartlett, Willard. Legal Ethics: An Address Delivered at Commencement Exercises of Albany Law School in the Hubbard Course on Legal Ethics (June 4, 1907).

- Section 110.10 of the New York Penal Law states, “If the conduct in which a person engages otherwise constitutes an attempt to commit a crime pursuant to section 110.00, it is no defense to a prosecution for such attempt that the crime charged to have been attempted was, under the attendant circumstances, factually or legally impossible of commission, if such crime could have been committed had the attendant circumstances been as such person believed them to be.”

- In Memoriam, 239 NY 642.