Two years after the close of the Civil War, forty-year-old Francis M. Finch, an Ithaca lawyer, unexpectedly (as he later admitted) struck a major chord in the American consciousness with his poem, The Blue and the Gray, published in the Atlantic Monthly in September 1867. Through its message of reconciliation by honoring the war dead, North and South, the poem became an inspiration for Decoration Day, later renamed Memorial Day. It is said that Finch was inspired to write the poem by a story he came across in the New York Tribune, about a group of women from Columbus, Mississippi, who decorated the graves, with flowers, of both Confederate and Union soldiers in their local Oddfellows Cemetery. The poem’s first and last stanzas reflect the sentiment of a Nation joined in mourning all its war dead:

By the flow of the inland river,

Whence the fleets of iron have fled,

Where the blades of the grave-grass quiver,

Asleep are the ranks of the dead:

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment day;

Under the one, the Blue,

Under the other, the Gray.

. . .

No more shall the war cry sever,

Or the winding rivers be red;

They banish our anger forever

When they laurel the graves of our dead!

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment day;

Love and tears for the Blue,

Tears and love for the Gray.

Finch later said that he wrote the poem without any notion that it would lead to the establishment of Memorial Day.

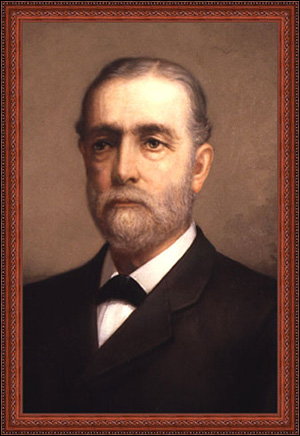

A Lifelong Ithican

A lifelong Ithacan, Finch was born June 9, 1827 in a village founded only twenty years earlier by Simeon DeWitt, the State Surveyor General. DeWitt predicted that Ithaca’s “advantages and situation cannot fail of giving it a rapid growth and making it one of the first inland places of trade.” Ithaca, at the head of Cayuga Lake, lay within the northern portion of what was later to become Tompkins County; DeWitt assigned this area to the New Military Tract, which was drawn up to give veterans lands in payment for their past military service during the Revolutionary War. Before the War, the Cayuga Indians, one of five-later six-tribes that made up the Iroquois Confederation, called the area home, but their villages and crops were destroyed by Major General John Sullivan at the direction of George Washington.1 Less than fifty years later, at the time of Finch’s birth, Ithaca had become an anchor of the Ithaca-Owego Turnpike, a newly built road over which goods flowed southward. Indeed, the opening of the entire Erie Canal in 1825 transformed Ithaca into a significant port. Local products, lumber, wheat, whiskey, oats, and shingles, were shipped out of Ithaca, and salt, plaster, limestone, and barley were brought in to the port. DeWitt’s prediction had come to pass.2

After his early years in Connecticut, Finch’s father, Miles Finch, settled there some time before 1820 and became a prominent merchant. In that position, the elder Finch undoubtedly benefitted from the recent developments of the Canal and the Turnpike. Miles’ parents were Nathaniel Finch, a clergyman, and Sarah Ferris; an uncle, John Finch, was a pioneer settler in the vicinity of Canandaigua around 1800. Miles Finch married Tryphena Farling in 1825; Francis was their firstborn of six (five sons and one daughter). Sons Edgar M., William Floyd, and Dudley F., followed their father’s footsteps and became proprietors of local hardware, dry goods, and book stores. Ferris Finch, another son, migrated to Washington and held a position there in government and also had some success as an artist. The Finch’s only daughter, Mary, first married Dr. Louis Sibley, and then Dr. T.S. Strong, pastor of the Dutch Reform Church.

Finch was educated at Ithaca Academy and thereafter entered Yale College at the beginning of his sophomore year. At Yale, he was known as something of a song writer. Andrew Dickson White recalled that:

All thru my college course at Yale, I had joined in the singing of his songs. Many songs had been written during the previous history of Yale, but those written by ‘Finch of ’49’ differed from most others in the fact that, as Carlyle once said of certain other true poems, they ‘got themselves sung.’

One of these was a smoking song that began with the lyric, “floating away like the fountain’s spray.” Others were entitled, “Gather Ye Smiles,” “Linonia” and “The Last Cigar.”* In his senior year at Yale, Finch was Class Poet and an editor of the Yale Literary Magazine. White also recalled that:

He had recently left college when I entered it, but his memory was still cherished, not only as a song writer, but as one of the very first scholars, and essayists in his class. There seemed, also, something in his character and influence which had left much more than an ordinary impression in that little college world.

The Poet

Finch graduated in 1849, valedictorian of his class-and member of Skull and Bones-and returned to Ithaca to study law.3 Admitted to the bar in October of 1850, he happily settled into his long career as a local country lawyer. On May 25, 1853, he married Elizabeth A. Brooke, of Colchester, Connecticut, Two months later, he attended the centennial celebration of the Linonian society at Yale, and read a poem that in part became quite popular, known as “Nathan Hale” after the Revolutionary War patriot who was captured and hanged by the enemy. The poem tells of the last and greatest moments of young Hale’s life:

To drum-beat and heart-beat,

A soldier marches by:

There is color in his cheek,

There is courage in his eye,

Yet to drum-beat and heart-beat

In a moment he must die.

. . .

Neath the blue morn, the sunny morn,

He dies upon the tree;

And he mourns that he can lose

But one life for Liberty;

And in the blue morn, the sunny morn,

His spirit-wings are free.

. . .

But his last words, his message-words,

They burn, lest friendly eye

Should read how proud and calm

A patriot could die,

With his last words, his dying words,

A soldier’s battle-cry.

. . .

From the Fame-leaf and Angel-leaf,

From monument and urn,

The sad of earth, the glad of heaven,

His tragic fate shall learn;

And on Fame-leaf and Angel-leaf

The name of Hale shall burn.

Despite his gifts, however, Finch described his efforts at poetry as “only incidents along the line of a busy and laborious life.” He and his wife had four children: Robert Brooke, Miles Francis, Mary Sibley, and Helen Elizabeth. Their home was at Fountain Place-a little street close to Cascadilla Creek and not far from East Hill and Cornell University. According to his daughter Mary, Finch was a Republican and a member of no church. Cornell Professor (later Dean) Edwin Hamlin Woodruff remembered that:

From the time of his graduation from college until he reached the age of 43, his life was that of the highest type of the country lawyer, in a prosperous and intelligent community. His clients and friends were his neighbors, the plain sturdy people of the thoroughly American village of that day, and of the surrounding farms. To paraphrase an utterance of Goldwin Smith’s in referring to this same community: ‘Such villages and farms are the real pillars of American society; they save the country from sensational journalism and the stock exchange.’

Finch’s most renowned client during this period was an indeed a local man, but one who nevertheless appears to have inspired much sensational journalism, for he was serial killer and philologist Edward H. Ruloff. True to Woodruff’s observation that Finch represented his neighbors, Finch and Ruloff had once studied Greek together at Ithaca Academy.

While Finch was still a student, Ruloff was arrested for the kidnapping of his own wife (who never reappeared) and spent ten years in state prison at Auburn. Upon his release, he was then indicted, tried, and convicted for the murder of his young daughter (who disappeared at the same time as her mother). Because Ruloff’s trial counsel, renowned attorney Joshua Spencer, passed away after the trial, local counsel Boardman & Finch represented Ruloff in the Court of Appeals, and the job of briefing and arguing the case fell to Finch. Finch’s adversary was former United States Senator Daniel S. Dickinson. The night before the argument in Albany, Dickinson spotted Finch in the hotel and asked him whether he had brought his rather voluminous brief down by way of a freight car. Despite this taunting, Finch held his ground-in his first argument at the Court of Appeals.

The case was heard on the issue of “whether there be a rule of law, in respect to the proof in cases of homicide, which does not permit a conviction without direct proof of the death, or of the violence or other act of the defendant which is alleged to have produced death” (Ruloff v. People, 18 NY179, 184 [1858]). The prosecution had provided evidence at trial that Ruloff and his wife, Harriet Schutt, had an unhappy marriage and that, while Harriet and their daughter were seen alive and well by a neighbor on June 24, 1845, they were never seen since. On June 25th, Ruloff unloaded a box from his house into a borrowed wagon and drove off; on the 26th he returned with the wagon and box, and had in his possession his wife’s ring. Ruloff soon fled to Chicago and claimed his wife and daughter had died six weeks earlier on the Illinois river. A search of Ruloff’s house revealed that a heavy cast iron mortar and two flat irons were missing; the house was in disarray with clothes on the floor and dishes unwashed. The jury convicted Ruloff and his conviction was affirmed by the intermediate appellate court.

Combining Poetry and Law

Writing for the Court of Appeals, however, Chief Judge Alexander S. Johnson ordered a new trial.4 The Court upheld Lord Hale’s rule that a person may not be convicted of murder “unless the fact were proved to be done, or at least the body found dead” (18 NY at 185, quoting 2 Hale’s P. C., 290). Chief Judge Johnson explained that “where the fact of death is not certainly ascertained, all mere inculpatory moral evidence wants the key necessary for its satisfactory interpretation, and cannot be depended on to furnish more than probable results” (18 NY at 1848).

Finch later quoted these words in a preamble to his lengthy poem about Ruloff entitled “His Side of the Story.” In the poem, Finch imagines Ruloff in his prison cell, on the eve of his execution for other murders, committed after the reversal in the case involving his child. In Finch’s poem, Ruloff is receiving a guest who has come to learn why Ruloff murdered his family:

Again?—Ah, well!—

Please take a chair. —

I feel my parlor seems quite bare,

And dull and dismal stays the best

That I can do for friend, or guest.

My cobweb curtains blur the light

That tangles in their meshes. White,—

Which is the bride of colors,—here

Glooms into prison dusk. The cheer

Of careful homes one can but miss

In corridor so blank as this.

. . .

I’ve watched the gnaw of rust on bar,

From red of morn to white of star,

For many days.

Remorse.—It may be!—

In Finch’s poem, Ruloff seems to provide a motive for the murders: he was cuckolded by another man. Yet he never quite owns up to the killings. In the final stanza, Ruloff is unwilling to accept responsibility:

What? – Where, then,

Are wife and child? – And how & when

Return unharmed?—

Have I not said,

If living still or long since dead?

Beg pardon.—Thought I had. Why what

Has talk of hour been aiming at?

No matter though: the night grows late

And sleep is near.—No need to wait:—

But come to-morrow when bell taps

Death signal.

Tell you then, perhaps!

Ruloff was again the subject of an appeal to the Court of Appeals, on the issue of photographic evidence of the deceased admitted at trial, though Finch did not represent him (45 NY 213 [1871]). Ruloff was hanged in 1871, but not forgotten.5 Indeed, he was later touted as “The Great Criminal and Philologist” in a 1900 essay by Samuel D. Halliday, known as a “distinguished member of the bar of Tompkins County, New York, and a public spirited citizen of Ithaca.” The essay was published in 1906 by the DeWitt Historical Society of Tompkins County, and included, in a prefatory note, a letter written by Judge Finch to Halliday on the subject of Finch’s argument in the Ruloff case at the Court of Appeals.6 Finch explained that:

because along the line of discussion [Chief Judge Johnson] occasionally used the words “direct,” “direct and positive,” “direct and certain,” the case was reported as requiring direct proof. That always seemed to me somewhat too strong, and yet it has been followed in numerous cases, and finally has been put beyond any question by the explicit terms of the Penal code. The distinction I drew, with much study and care, has thus ceased to have any importance except that of an historical character; but it at least serves to illustrate one of the ways by which, through judicial interpretation, the law develops.

Indeed, the rule developed into what was known as the Ruloff rule, and was incorporated into section 181 of the Penal Code (by chapter 384 of the Laws of 1882) and then became section 1041 of the Penal Law of 1909. It stated that “no person can be convicted of murder or manslaughter unless the death of the person alleged to have been killed and the fact of killing by the defendant, as alleged, are each established as independent facts; the former by direct proof and the latter beyond a reasonable doubt.”7 The Ruloff rule was not carried forward into the Penal Law of 1965, because it had been widely criticized as having the potential for rewarding the professional or meticulous killer who successfully eliminates all direct evidence of the death of the victim. As a matter of common law, the rule remained in effect until 1982 when it was overruled in People v. Lipsky (57 NY2d 560 [1982]), written by Judge Bernard M. Meyer.

Coincidentally, poetry also played a role in the Lipsky case. The defendant, Leonard Lipsky, had confessed to killing Mary Robinson, a Rochester waitress and sometime prostitute, but Robinson’s body had never been found, because Lipsky had driven it about three hours south of Rochester and dumped it down a gully. The prosecution introduced evidence of Lipsky’s confession, as well as articles belonging to Robinson that had been found in Lipsky’s apartment. Also introduced before the jury, and included in the unanimous Court of Appeals opinion, was Lipsky’s poem implicating himself in the murder.8 In overruling the Ruloff rule, the Court upheld Lipsky’s conviction, concluding that, notwithstanding the missing corpse, there was sufficient circumstantial evidence of Lipksy’s guilt to present the question to the jury (57 NY2d at 566-573).

Finch was also integrally involved in perhaps the most lasting accomplishment of early Ithaca: the establishment of the land-grant for Cornell University. Ezra Cornell had previously relied on Finch, in 1863, when drafting a charter for the Library Association of the Cornell Public Library. Finch later wrote to Cornell that the library had become a great success: “Some boys that I have seen for months roaming the streets nights are there every evening, quiet & orderly and almost unwilling to leave at 9 o’clock.” In his autobiography, Andrew Dickson White recalled that he and Cornell relied on Finch, “a man of noble character, of wonderfully varied gifts, an admirable legal adviser, devoted personally to Mr. Cornell, and no less devoted to the university.” White explained that as Cornell was dying, in 1874,

[Finch] set to work to disentangle the business relations of Mr. Cornell with the university, and of both with the State. Every member of the board, every member of Mr. Cornell’s family,-indeed, every member of the community,-knew him to be honest, faithful, and capable. He labored to excellent purpose, and in due time the principal financial members of the board were brought to Ithaca to consider his solution of the problem. It was indeed a dark day; we were still under the shadow of ‘Black Friday,’ the worst financial calamity in the history of the nation. . . . In a few days Mr. Cornell was dead; but the university was safe. Mr. Finch’s plan worked well in every particular; and this, which appeared likely to be a great calamity, resulted in the board of trustees obtaining control of the landed endowment of the institution, without which it must have failed.

So trusted was Finch that in 1868, President Ulysses S. Grant named him Collector of Internal Revenue for the Twenty-sixth District of New York, headquartered in Ithaca, a position he held for four years.

On May 25, 1880, Governor Alonzo B. Cornell appointed Finch to the Court of Appeals, to fill the vacancy occurring when Judge Charles J. Folger became Chief Judge. White remembered, “[o]ne thing peculiar to him I frequently noticed and that was the wonderful clearness of his mind and his amazing power of writing legal opinions straightaway, in a hand like cooper plate, with never an erasure or correction. Many others noted this characteristic and it was therefore no surprise to his friends when, though he had never before held judicial office, he was appointed to a seat in the Court of Appeals.”

Judge Finch was reappointed on January 1, 1881, and then elected to a term of fourteen years on November 5, 1881. In his years on the Court, Judge Finch wrote more than 750 opinions-in his first year he wrote about 25, and in his last year he wrote more than 40. As his friend and Cornell colleague, Dean Ernest W. Huffcut aptly remarked, Judge Finch’s “opinions are scattered along the highway of our law from volume 81 to volume 148 of our Reports of the Court of Appeals.”

On the occasion of Judge Finch’s seventy-fifth birthday, Judge John Clinton Gray, who had served on the Court with him, wrote this:

It would be a grateful task to speak of his great talents as a jurist, and those admirable and gentle personal traits which endeared him to all who were privileged with his friendship. As Judge, his opinions were conspicuous for the conclusiveness and clearness of their reasoning and they are among the most valuable of those which have given repute to the reports of this court. Remarkable for their purity of English and elegance of composition, they lack nothing in force or logic. Their discussion of questions was characterized by a breadth of thought and by a grasp of the arguments for and against which satisfied the bar. His associates in the court found him wise, firm and helpful in consultation, and they found him lovable in daily intercourse.

Back to Ithaca as Cornell Law Dean

Following his retirement of the bench, Judge Finch became Dean of the Faculty of Cornell Law School, and a Professor of the History and Evolution of Law. Finch also served as President of the New York State Bar Association in 1899.

The Judge died at his home in Ithaca on July 30, 1907, at the age of 80, after a decline in his health. His daughters and brothers were by his side, his wife having predeceased him by fifteen years. Ithaca had grown from country village to thriving city during the span of his life, and had him in large measure to thank for it. In his eulogy of his friend, White said that “[h]e has always seemed to me to be one of the best examples of true American character.”

Progeny

The Judge has three great-granddaughters through his daughter, the late Helen Finch (d. 1948) of Ithaca, New York, who married Professor Othon G. Guerlac (1870-1933). These granddaughters are the children of Rita Carey and the late Professor Henry Edward Guerlac (1910-1982): Lucy Battersby of Bloomington, Indiana; Anne-Christine Tomovich of Lakewood, Colorado; and Professor Suzanne Guerlac of Berkeley, California. The four great-great-grandchildren are Catherine Guerlac, Justine Olivia Battersby, Julian Henry Battersby, and Mielle Christine Turner. There are also great-great-great-grandchildren.

Before joining the Cornell University faculty in 1946, Professor Henry E. Guerlac was on the faculty at Harvard, the University of Wisconsin, and M.I.T. He was awarded the George Sarton Medal by the History of Science Society in 1973, was named a Guggenheim Fellow in 1978, and in 1982 was named Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur by the French government. His books include Science in Western Civilization, Newton on the Continent, and Lavoisier: The Crucial Year, for which he received the Pfizer Prize in 1959. At the time of his death Professor Guerlac was completing an annotated edition of Newton’s Opticks, which was first published in 1704. (The above according to the guide to his papers, at Cornell.)

Professor Othon G. Guerlac was the author of The Storm Center of French Politics, Citations Francaises (editor), Jaures: The Present Leader of French Socialism, and Two French Premiers: Waldeck Rousseau and His Successor. Rita Guerlac was editor of Themes of Peace in Renaissance Poetry.

Professor Suzanne Guerlac, now at the University of California at Berkeley, is author of The Impersonal Sublime: Hugo, Baudelaire, Lautreamont; Literary Polemics: Bataille, Sartre, Valéry, Breton (co-winner of the Scaglione Prize); and Thinking in Time: An Introduction to Henri Bergson. Lucy Battersby is on the administrative staff at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Abt, Henry Edward, Ithaca, Ross W. Kellogg (1926).

Appletons Encyclopedia, Francis Miles Finch http://famousamericans.net/francismilesfinch (accessed December 6, 2005).

Article, New York Times, May 27, 1923, p. 1.

Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White, Volume 1, The Century Co. (1905).

Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, Columbia University Press (1985).

Cayuga Waterfront Trail http://waterfront.data3m.com/?t’71 (accessed November 29, 2005).

Chadbourne’s Public Service of the State of New York.

Collection of newspaper obituaries in the New York State Library.

Cornell Public Library http://rmc.library.cornell.edu/presidents/img/large/02_Finch.jpg (accessed December 5, 2005).

Cornell University Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

Cornell University Exercises in honor of Francis Miles Finch upon the occasion of his seventy-fifth birthday (Cornell University 1902) (booklet on file with the author).

Court Register 1907, at 6.

Crain, In Search of Lost Crime: Bloated Bodies, Bigamous Love, and Other Literary Pleasures of the 19th-Century Trial Transcript, 2002 Aug Legal Aff 28 (July/August 2002).

DeWitt Historical Society of Tompkins County, including Publications No. 1, 2d ed., Ithaca Democrat Press (1906), and from the Ruloff Collection (V-2-1-9).

Humor and Literature on the Bench, The Green Bag, Volume VIII, at 264-265 (1896).

Kammen, History of Tompkins County (2003) (accessed November 28, 2005).

Kunitz & Haycraft (eds.), American Authors 1600-1900: A Biographical Dictionary of American Literature 272, H.W. Wilson Co. (1938).

Record of the Graduated Members of the Class of 1849 of Yale College, 1849 to 1894, The Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Press (1895).

Steyn, Our Last Cigarette: The fading glories of the smoking song, Slate (1997)

(accessed December 5, 2005).

Thurston, Hearsay of the Sun: Photography, Identity, and the Law of Evidence in Nineteenth-Century American Courts, American Quarterly, Hypertext Scholarship in American Studies (1998) http://chnm.gmu.edu/aq/photos/index.htm (accessed November 23, 2005).

Trustee Minutes, 1880, Hamilton College Library Archives.

There Shall be a Court of Appeals, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State Of New York, (1997) (booklet on file with the author).

Van Cleef, Francis Miles Finch, 40 The Cornell Era 1, at 1 (October, 1907) (booklet on file with the author).

Yale College and University Records.

Published Writings Include

Aurora Bay, 8 The Cornell Review 1, at 1 (October, 1879)

The Blue and the Gray, originally published in The Atlantic Monthly, September 1867; republished in Civil War Poetry, An Anthology, ed. Paul Negri, Dover Publications (1997).

A Poem, delivered before the Linonian Society of Yale College at its Centennial Anniversary, The Linonian Society (1853)

Taghkanic, 40 The Cornell Era 1, at 9 (October, 1907).

Endnotes

- Washington ordered Sullivan that the soldiers were “to chastise and intimidate hostile nations; to cut off their settlements; destroy the next year’s crops; and do them every other mischief which time and circumstance will permit.” Sullivan later wrote, “I flatter myself that the orders with which I was entrusted are fully executed, as we have not left a single settlement or field of corn in the country of the Five Nations.”

- Ithaca was also home to a small number of both enslaved and free African Americans. In addition to being the year of Judge Finch’s birth, 1827 was, momentously, the year slavery was abolished in New York State, freeing those slaves who had been brought to the Ithaca area by settlers from the south.

- In 1880, Finch received an honorary LLD from Hamilton College. In 1889, he received an honorary LLD from Yale.

- Apparently, some of the local Ithaca folk were so incensed by the Court of Appeals ruling that they planned to assemble and organize their own “court” to be presided over by a judge named “Lynch” – they were provoked, it seems by the publication of a pamphlet entitled “Shall the Murderer Go Unpunished!” It called upon “those who wish justice done to the murderer to meet at the Clinton House, in Ithaca, on Saturday, March 12th, 1859, at 12 o’clock noon. It will depend on the action you take that day whether Edward H. Ruloff walks forth a free man or whether he dies the death he so richly deserves.” The pamphlet was signed “Many Citizens.” Finch and his partner, Douglas Boardman, were also at risk: at noon on the day of the planned lynching, George W. Schuyler allegedly went into the offices at Boardman & Finch and told them to avoid walking past Clinton House, because the mob there was so angry it might turn on Ruloff’s lawyers.

- After his execution, Ruloff’s head was removed from his body and a plaster cast was made of it to enable a study of it; his brain was weighed, studied, and then stored at Cornell University.

- The entire letter reads:

“Dear Mr. Halliday:

“I have read your historical sketch of the case of Ruloff, and of his life and crimes with great interest. Your investigation has been accurate and exhaustive, and goes even beyond my memory of the man. I regard the view you have expressed of the point really made and decided on his appeal to the court of last resort as substantially correct . . . For I did not contend that death, as an element of the corpus delecti, should always be proved by direct evidence. I avoided all discussion resting upon the difference between direct and indirect proof, and argued that, whatever its character might be in that respect, it must at least be certain and unequivocal and such that, conceding its truth, the supposition of remaining life would not be a rational possibility. I then insisted that this certainty of proof was required by Lord Hale’s rule, and that the death was never sufficiently established when the sole proof of it was the unexplained disappearance of the person supposed to be murdered. I thus refused to stand upon the theory of direct evidence as inevitably required for two reasons: one, that the text-books more or less disavowed such a rule, and the other, that I could imagine a case in which the death might be made absolutely certain, although the evidence might be wholly or partly indirect. And I adhered to my position so rigidly and closely that my adversary, who was annoyed bu it, claimed that I had raised a new question, not covered by any exception in the case.

“The decision rendered by the Court determined two things: First, that the rule of Lord Hale was the true rule of law and had never been judicially departed from; and second, that ‘the rule is not founded in a denial of the force of circumstantial evidence, but in the danger of allowing any but unequivocal and certain proof that some one is dead to be the ground on which, by the interpretation of circumstances of suspicion, an accused person is to be convicted of murder.’ These two propositions followed closely the line of the argument and settled the case. It was not needed to further narrow the rule by confining it to direct evidence, and the Court nowhere said that in so many words; but because the Judge quoted the question raised in the trial court, which was a demand for direct proof, and because along the line of discussion he occasionally used the words ‘direct,’ ‘direct and positive,’ ‘direct and certain,’ the case was reported as requiring direct proof. That always seemed to me somewhat too strong, and yet it has been followed in numerous cases, and finally has been put beyond any question by the explicit terms of the Penal code. The distinction I drew, with much study and care, has thus ceased to have any importance except that of an historical character; but it at least serves to illustrate one of the ways by which, through judicial interpretation, the law develops.” - In People v. Johnson (140 NY 350 [1893]), Judge Finch had the opportunity to apply the Ruloff rule, concluding that “the death, and the violence which caused it, alleged in the indictment, were proved in this case by direct evidence as the law now requires.”

- Lipsky wrote:

“To crush out a life with a hand or a heel

To be carelessly senseless and not even feel

To treat one as nothing and not even real

to be as a jackal, a thief who did steal

I was such a man, and it’s a part of me now

I was such a fool and can’t even tell how I did such a thing

Now, it weighs on my brow and I think of the peace such an act won’t allow

But still I live on and remember it well

Yet still I must live to remember the hell

I can never let go of the body that feel, and it tears me to pieces where my thoughts on this dwell

I can never be free of this feeling inside

I will never be able to successfully hide

And there is no way to share the tears that I’ve cried

So I now live for two; by my hand one has died.”

* A researcher presented a paper at the Doylestown Institute in 2019 that identified contrary information about the author of “The Last Cigar,” indicating instead Judge Finch wrote “The Smoking Song.”