Members of the Folger family, including the immortal Benjamin Franklin, were known for their superb intellect. Judge Folger was no exception. In 1881, he retired from the Court of Appeals in his eleventh year on the Court, the last of which he served as Chief Judge, to accept an appointment from President Chester Arthur as Secretary of the Treasury. At the time of his appointment, a New York Times article stated that:

‘[t]he [Folger] family have ever been distinguished for habits of industry, temperance, frugality, and a high regard for moral and social duties. Their children, like their parents, have generally shown skills in mechanics-there are but few exceptions-and in some instances have evinced extraordinary powers in mathematics and unusual readiness to acquire general knowledge.’ All our readers will readily recognize the close truth of this diagnosis as touching Ben Franklin, while those who know Secretary Folger say that his natural aptitude for questions in finance will prove of inestimable service to him in his new position.1

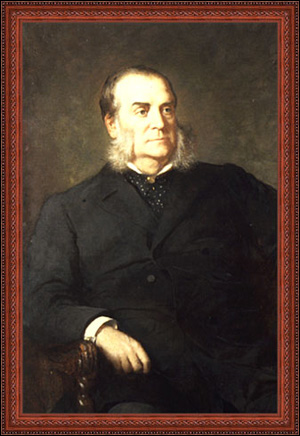

Born on April 16, 1818 “of the best New-England stock,”2 Judge Folger was the son of Thomas Folger, whose family had settled on Nantucket nearly 200 years prior, and Hannah Gateskill from London, England. He received his education at the common schools of Nantucket and at Plainfield Academy in Connecticut. Judge Folger and his family moved from Nantucket to Geneva, New York in 1831. In 1836, he graduated at the top of his class from Hobart College, which at the time was called Geneva College. He studied law at Canandaigua, New York in the office of Mark H. Sibley and Alvah Worden and with Bowen Whiting of Geneva and John M. Holley of Lyons. Judge Folger and his wife, Susan Worth Jr., were married on June 18, 1844. They had three children – Susan, Jennie, and Charles.

A Successful Politician

After his 1839 admission to the bar, Judge Folger returned to Geneva, opened a law office and launched a successful political career.3 Judge Folger followed the Silas Wright wing of the Democrat Party. He later joined the Barnburners, a radical element of the Democrat Party that opposed slavery and seceded from the Democratic state organization in 1847.4 Like many fellow Barnburners, Judge Folger left the Democrat Party to help organize the Republican Party in New York.

At nearly six-foot-tall, Judge Folger was “large in body, grave and dignified in demeanor, but animated in the excitement of conversation or debate.”5 His “prodigious physical strength” enabled him to save the life of a train engineer in the early 1850s. According to a New York Times article, a moving train hit a stationary train from behind, killing a man caught between the two trains. Those who witnessed the incident grew angry and a riot ensued.

“The indignation of the crowd at the station was so intense that an attempt was made to lynch the offending engineer then and there. They had dragged him from his engine and were about to proceed summarily to punish him, even to the taking of his life, when Charles J. Folger, then a young and very athletic man, plunged into the crowd, and, throwing the rioters right and left, took the engineer under his personal charge and protected him from violence.”6

When this incident occurred, Judge Folger’s remarkable judicial career was already well underway. It began with an 1844 appointment to the Ontario Court of Common Pleas. He also served as Master and Examiner in Chancery until the adoption of the 1846 Constitution abolished that court. In 1851, he was elected County Judge of Ontario County and held that position for four years.

Judge Folger also engaged in local politics. He served as President of Geneva’s Board of Trustees and, in 1857, became Geneva’s first chief of police. He owned the village’s first jail, or “lock-up,” and rented it to the village for $80 a year.7

A Distinguished Senator

According to Judge Charles Andrews, Judge Folger entered the Senate in 1861 without previous legislative experience and, in his first term, rarely addressed the Senate because he was timid and did not trust his debating skills. Judge Andrews told the attendees of a Hobart College Commencement address held after Judge Folger’s death that,

on one occasion a bill was being pressed which had met with [Judge Folger’s] strong opposition in committee, but seemed likely to pass the Senate. He sat uneasily in his chair hesitating, and yet not daring to rise, until at the last springing to his feet he assailed the bill with such passionate strength of argument and invective that he carried the Senate and the bill was defeated.8

Judge Andrews added that Judge Folger’s “timidity passed away” and his speeches “were characterized by breadth, logic and a kind of sledge-hammer force calculated to carry conviction. He took and gave blows, and when he struck it was with no gloved hand.”9

A distinguished State Senator, Judge Folger was president pro tem for four years and Chairman of the Judiciary Committee. A New York Times article described him as an “uncompromising enemy of all jobbery and corruption”10 In 1864, he authored what became known as the Folger Anti-Strike Bill, titled “An act to punish interference with employers and employees,” which made it unlawful for workers to unite for the purpose of conducting a strike.11 Labor unions protested the bill vigorously in all major cities throughout the state, forcing it to a halt in the Judiciary Committee. In New York City’s Tompkins’s Square, 15,000 workers denounced the proposed bill. One delegate at the New York City meeting called upon all present to pledge themselves to defeat Judge Folger for governor, should he become a candidate, as it was thought at the time to be his ambition.12

While serving in the Senate, Judge Folger was appointed as a delegate to the 1867 New York Constitutional Convention. In July 1867, he received a letter from Susan B. Anthony, who lobbied his support for women’s suffrage at the Convention. She stated that if the new Constitution gave women the right to vote, “the thousands of women of the state who believe women should have the right to vote will become the most active and powerful workers for the success of the new Constitution and all of us together with the Republicans could and would surely triumph.”13 She warned him that “any other course will be a failure,” adding that “suffrage is the one right which no one person or class has the right to give or withhold.”

Although Judge Folger’s response to Susan B. Anthony’s plea is uncertain, she may have had some effect on his attitude toward women’s rights. While Secretary of the Treasury, Judge Folger overturned a decision by Kenneth Raynor, solicitor of the United States Treasury, and granted Mary Miller of Louisiana a licence to captain a steamboat on the Mississippi River.14 Solicitor Raynor had denied Mary Miller a captain’s license despite the fact that examiners had found her competent to command a steamer.

Although Judge Folger’s role, if any, in the suffrage issue is unknown, he was an influential Convention delegate in other respects. The Convention members appointed him to draft an address to the people of the State that summarized the proposed constitutional amendments. His address emphasized the proposed amendments that were to stop the bribery of public officials and the improper influences of elections. Perhaps Judge Folger’s most important role at the Convention was chairman of the fifteen-member judiciary committee. Aided by Judge George F. Comstock (who had served on the Court of Appeals from 1856-1859), Judge Folger framed the judiciary article under which he would soon thereafter be elected associate judge of the Court of Appeals. Article VI provided that the Court of Appeals would consist of seven members – a Chief Judge and six Associate Judges – elected to fourteen-year terms. This contrasted with the then-existing eight-judge Court consisting of four judges elected statewide for an eight-year term and four elected Supreme Court Justices who served ex-officio for one-year terms.15 The judiciary article was the only part of the proposed new Constitution that was ratified by the people.

Judge Folger resigned his position as Senator in 1869 to accept the appointment of Assistant United States Treasurer in New York, a position he held until elected to the Court of Appeals in 1870. Although Judge Folger was a Senator at a time when “the public treasury was open to plunderers” and “legislation was sold for money,” he “emerged from the murky atmosphere of that time with character untouched, and retired from the Senate with stainless honor, enjoying the public confidence and esteem.”16

A Respected Jurist

Despite his unblemished reputation, Judge Folger’s election to the Court of Appeals in 1870 was surrounded by controversy. Word spread that his and Charles Andrews’ victories were secured by votes from Boss Tweed’s Democrat machine. According to one critic, F. A. Conkling, the “election of Judges Folger and Andrews, by beating their colleagues on the Republican ticket, was effected through an understanding between Tweed and the Republican leaders, by casting a number of machine Democratic votes for those two Republicans in Democratic districts of New York City.”17 Claiming that the election was “one of the most shameful that has ever disgraced the City annals,” the New York Times stated that the infamous Canal Ring and Boss Tweed fixed the election because they knew “that sooner or later the swindling nature of the so-called ‘contracts’ and ‘awards’ by which they were profiting would be discovered and restitution demanded. To head off assaults of this kind it was necessary to influence the court of highest resort.”18

In 1870, Judge Folger received a Doctor of Laws from Hobart College. After 10 years on the bench as an Associate Judge, he became Chief Judge, filling the vacancy created by Chief Judge Sanford E. Church‘s death in 1880. Later that year, he received the Republican nomination for Chief Judge and was elected to that position, which he held for only a year and a half. In 1881, he resigned to become President Chester A. Arthur’s Secretary of the Treasury.

During his tenure on the Court of Appeals – spanning 11 years and 40 volumes of New York Reports – Judge Folger was known among his colleagues for his careful preparation, sharp intellect and solid judgment. Judge Andrews stated that “[i]f I were called upon to characterize Judge Folger’s most prominent traits as a judge, I should say they were largeness and breadth of view, combined with a disposition to adhere to precedents, although they might not satisfy his judgment, great conscientiousness, the habit of patient, assiduous investigation before reaching conclusions, and absolute independence and fearlessness in declaring them.”19 “His mind was like a prism,” Judge Andrews continued,

separating every argument into its original elements, and receiving light from all quarters. He regarded nothing as unworthy of examination, and when this process analysis was past, however much he may have doubted before, he generally reached the solid ground of conviction, and then collecting the results of his investigation, he stated his conclusions in the words of nervous force and energy, though often quaint and odd, paying little regard to the niceties of style or polished diction.20

Upon Judge Folger’s retirement, the Judges of the Court drafted a letter honoring him; the letter and his response are published in 84 NY Preface. His colleagues described Judge Folger’s opinions as “second to none” and “clear, learned, and able discussions of the questions considered.”21 In response, Judge Folger wrote that

the dearest of my recollections of the Court of Appeals will be of the harmony of intercourse, the uniform courtesy, the mutual confidence, the unvarying respect for one another, the cordial appreciation, the brotherly love, that held us in happy, personal and official relations. When I reflect on all these things, I wonder almost to sobbing, that I could have been led to give up the place of formal Head of such a Court, the nominal Chief of such a body of Judges.

A Loyal Treasury Secretary

With “great reluctance,” Judge Folger left the bench to accept President Arthur’s appointment “because he felt that he could not in honor disregard the demand which was made upon him.”22 Despite pleas from his associates at the Court to decline the invitation, Judge Folger “yielded to what he deemed his duty to his party, but more than all to the demand of personal friendship and to the sentiment of personal loyalty, which was one of his chief characteristics, and which when appealed to he never set aside or disregarded.”23 In a letter to Judge Andrews, Judge Folger stated: “You and I know very well that I was not only reluctant, but strongly opposed to taking this place, and that nothing but the condition of things as I found them in Washington when I came here in October brought me to consent.”

Judge Folger immediately applied himself to learning the details of the operations of the treasury and felt it his duty to eliminate abuses and protect the treasury from unlawful and improper intrusion. As Secretary, he reduced the public debt and presided over the greatest surplus the government had ever had at that time. Observing that times had changed since the 1789 Treasury Secretary was charged with devising plans for collecting revenue, he stated that “[w]hat now perplexes the secretary is not wherefrom he may get revenue enough for the pressing needs of the government, but whereby he shall turn back into the flow of business the more than enough for those needs, that has been drawn from the people.”24 He considered several options, including using the surplus to pay off the federal debt. Ultimately, he advocated reducing the customs duties. Judge Folger also initiated the civil service administration in the Treasury Department.

An Unlikely Candidate

In 1882, Judge Folger received the Republican nomination for Governor of New York. An unlikely candidate, he received the Republican nod over the Republican incumbent, then-Governor Alonzo B. Cornell. Many Republicans felt that Judge Folger was the only man who could win, and that Governor Cornell could not be reelected. The Republican Party was divided, as Governor Cornell announced his determination to fight for renomination.25 Ultimately, however, the party nominated Judge Folger.

Some Republican officials asked Judge Folger to decline the party’s nomination. In an acceptance letter, Judge Folger stated “[a]s I sought not the nomination, as I was not glad when it came to me, as I could always have seen, and could now see, it go to another without one twinge of regret, I have no personal reason why I should not refuse it with alacrity. But the matter is not solely or chiefly personal. It has wider and vastly more important scope.”26 Judge Folger believed that his declining the nomination “would produce the utter collapse of the Republican party” because “on the late eve of a highly important election@ it would be impossible Ato name another person for the office who would be likely to meet with party acceptation.”27

Although he accepted the nomination, he neither campaigned nor resigned his cabinet office. Judge Folger stated that, if elected, he would aim “to be the representative of the whole party, subservient only to my duty to be the chief magistrate of the whole people, unmoved by the appeals of faction, unswerved by the appliances of private interests, acknowledging no claim of mere partisanship, looking supremely for the good of the Commonwealth.”28 He did not, however, get the opportunity to pursue that lofty goal. Grover Cleveland, then the obscure mayor of Buffalo who would become President in 1884, defeated Judge Folger by almost 200,000 votes – an unprecedented plurality. Judge Folger’s substantial loss allegedly damaged President Arthur’s influence such that his own nomination for the presidency became improbable.29 After the election, Judge Folger wrote that “[a]s I had anticipated defeat, with no ray of other expectation, I was not overcome or cast down when it came, and congratulated myself that the certainty that it would come saved me from much personal abuse.”30

At some point in 1884, Judge Folger became seriously ill while in New York and traveled to Geneva, hoping it would aid his recovery. Despite his deteriorating condition, he attended to his cabinet duties by reading and responding to messages from Washington. On September 4, 1884, Judge Folger died of, among other complications, a heart condition. Upon his death, President Arthur and many other Washington and New York officials gathered in Geneva for his funeral. His two daughters, then living in the Adirondacks, and son, Captain Charles Folger of Alexandria, Virginia, were among those who survived him. Judge Folger was buried in Geneva, by the side of his wife who had died seven years earlier.31

Many thought that the loss he suffered in the November 1882 Gubernatorial election caused him great sadness and shortened his days.32 The Judge, however, “did not believe that the ‘chief end of man’ was to hold office,” and, in relation to his candidacy for governor, stated, “I had much rather become a private citizen and take a place in some secluded room in the pursuit of my profession, with reasonable compensation for reasonable work, and end my days in quiet.”33 Indeed, his close friends knew that “he yearned to the last for his old place on the bench.”34 In May 1881, Judge Folger wrote: “I was in Albany for two hours the other day, regretful that the judges had left. I wished to see them in their silks. I did see their fine new room. How can they help but write ornate opinions?”35

Judge Folger contemplated retirement after fulfilling his duties as a cabinet member. Just two years before his death, then-Secretary Folger wrote:

When I am through with the job I now have on hand it will be high time for me to retire; to doze in the sunshine in the spring, to meditate in the shade in the summer, and to nod by the fireside in the winter, and in livelier moments to keep the spark of life in moderate glow by talk with a few friends, and communion with a few loved authors.36

Unfortunately, as Judge Andrews noted, Judge Folger did not have the opportunity to experience this pleasant retirement. He died as he had lived, “with the harness on, in the full strength of his intellect, still engaged in the discharge of his high duties.”37

Progeny

Judge Folger had three children-Susan, Jennie, and Charles. Charles married Vashti Susan Depew. Of that union, a daughter, Mirabel Depew Folger (1876-1946) married Orlo James Hamlin in 1899. The Hamlins became the parents of three children: Mirabel McCoy Hamlin, Hannah McCoy Hamlin, and Susan Darling Hamlin. Mirabel McCoy Hamlin married Robert A. Digel in 1923. They had five children, including Robert A. Digel, Jr., of Smethport, Pennsylvania. Orlo Hamlin’s father, Henry Hamlin, founded the Hamlin Bank and Trust Company of Smethport, Pennsylvania, which is active today, having celebrated its 125th anniversary in 1988. Robert A. Digel, Jr., Judge Folger’s great-great-grandson, is its chairman of the board, and his son, Martin J. Digel is president. The Eliza Starbuck Barney Genealogical Record lists both Judge Folger and his wife, Susan Worth Jr., who died in 1877. For information regarding the Folger family, visit the Nantucket Historical Society’s genealogy web page at http://12.46.127.86/bgr/BGR p/index.htm.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Bergen, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932 Columbia University Press (1985).

Browne, Some Characteristics of Charles James Folger, 30 Alb LJ 201, 284

Burnham, Leading in Law and Curious in Court, Banks and Brothers ‘ 143, at 115-117 (1896).

Chadbourne, The Public Service of the State of New York http://www.courts.state.ny.us/history/elecbook/chadbourne_coa/pg1.htm (last visited July 27, 2005).

Charles James Folger, 30 Alb LJ 201 (1884-1885).

Chester, Legal and Judicial History of New York, Vol I, National Americana Society New York, at 389-390 (1911).

Chester, Legal and Judicial History of New York, Vol II, National Americana Society New York,

at 210 (1911).

The Chief Judgeship of the Court of Appeals, 55 Alb LJ 204, 205 (1897).

Conkling, The Judiciary, reprinted from The Albany Times.

Current Topics, 1 Alb LJ 355, 356 (1870).

Dougherty, Legal and Judicial History of New York, Vol. II, National Americana Society New York (1911).

Dougherty, Constitutional History of the State of New York (1915) (2d ed.).

Harper’s Weekly, Oct. 8, 1870, at 653 (drawing).

History of Ontario County, New York and Its People, Vol. I at 168 (1911).

I. History of the Bench and Bar of New York, McAdam, et al. eds., New York History Company (1897).

Sams & Riley, The Bench and Bar of Maryland, A History 1634 to 1901, Vol. II, The Lewis Publishing Company (1901).

Smith, History of the Cabinet of the United States of America, The Industrial Printing Company, at 232 (1925).

There Shall be a Court of Appeals, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York, (1997) (booklet on file with the Court of Appeals).

Various articles published in The New York Times from the 1860s to 1884.

Whaleman’s Shipping List and Merchants’ Transcript, obituary, Sept. 9, 1884.

Published Writings

As far as we can tell, Judge Folger did not publish any books or articles of his own. He did publish a writing in connection with a law suit he brought against the United States to recover commissions made from his sales of internal revenue stamps while he served as Assistant Treasurer of the United States in New York. Known as AFolger’s Case,@ the 1877 opinion is reported at 13 Ct.Cl. 86. In denying his claim, the United States Court of Claims determined that the statute under which the Assistant Treasurer sold such stamps did not provide for his compensation. Judge Folger also published writings as a State Senator and as Secretary of the Treasury, many of which appeared in The New York Times. For example, he published his March 20, 1868 remarks to the New York State Senate concerning a bill to abolish the contract system associated with the canals and, in February 1882, The New York Times published a letter he wrote as Treasury Secretary concerning a bill that would prevent the over certification of checks by officers of national banks.

Endnotes

- The Folger Family, New York Times, Nov. 2, 1881.

- Id.

- See Chadbourne, The Public Service of the State of New York, http://www.courts.state.ny.us/history/elecbook/chadbourne_coa/pg11.htm (last visited July 27, 2005); Judge Charles J. Folger, New York Times, Aug. 25, 1880; see also Francis Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, 1985 at 114.

- See Judge Folger Appointed, New York Times, Oct. 28, 1881.

- Chadbourne, The Public Service of the State of New York, http://www.courts.state.ny.us/history/elecbook/chadbourne_coa/pg11.htm (last visited July 27, 2005).

- How Judge Folger Saved a Life, New York Times, May 22, 1880.

- City of Geneva, New York, Police Dept. History, http://www.geneva.ny.us/index.asp?Type’B_BASIC&SEC’%7B19C8C0D2-CF19-4FE8-8551-E85C0CB964AD%7D (last visited May 5, 2005) (available on file with the author).

- Andrews, Charles James Folger, Address at Hobart College Commencement, 32 Alb LJ 33, 35 (1886).

- Id.

- Judge Charles J. Folger, New York Times, Aug. 25, 1880.

- New York State AFL-CIO, A History of the New York State AFL-CIO, http://www.nysaflcio.org/documents/History.PDF (last visited May 5, 2005) (available on file with the author).

- See id.

- Susan B. Anthony Letter, dated July 7, 1867, Gilder Lehrman Online Exhibits, http://viking.coe.uh.edu/~mkalayci/cuin6397/final_project/suzi/4360_page3/4360_3.htm (last visited June 27, 2005) (available on file with the author).

- By All Means Commission the Ladies, Harper’s Weekly, Feb. 16, 1884, http://www.harpweek.com/09Cartoon/BrowseByDateCartoon.asp?Month’February&Date’16 (last visited July 15, 2005) (available on file with the author).

- There Shall be a Court of Appeals, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York, at 4 (1997).

- Andrews, supra note 8, at 35.

- Conkling, F.A., The Judiciary, at 5 (May 1890).

- Influence of the Canal Ring on the Court of Appeals, New York Times, March 31, 1875, at 1.

- Andrews, supra note 8, at 36.

- Id.

- Remarks on Retirement, 84 NY Preface.

- Andrews, supra note 8, at 37.

- Id.

- Charles J. Folger, Secretaries of the Treasury, Office of the Curator, http://www.treas.gov/offices/management/curator/collection/secretary/folger.htm (last visited July 1, 2005) (available on file with the author).

- See Platt, The Autobiography of Thomas Collier Platt, at 168 (1910).

- Mr. Folger’s Acceptance, New York Times, Oct. 3, 1882.

- Id.

- Id.

- The American Presidency, Encyclopedia Americana, Arthur, Chester Alan, http://ap.grolier.com/article?assetid’0022680-00&templatename’/article/article.html (last visited May 3, 2005) (available on file with the Court of Appeals).

- Andrews, supra note 8, at 38.

- See Secretary Folger Dead, New York Times, Sept. 5, 1884, at 1.

- Judge Folger’s defeat in the 1882 Gubernatorial election did not have a profound effect on him as many believed because, at least at that time, he did not desire to be Governor. On April 5, 1882, Judge Folger wrote,

“I do not want to be governor. Few will believe it. Few will think that I am not ambitious. Few will ever understand how my judgment and my desires yielded to friendship and a sense of duty, when I came (to the Treasury Department). I have proposed to myself to work steadily on in the place of trust, until the end. I am not ambitious. Give me a competency – nay, a little more, so that I can have pictures and books and horses – and friends about me – and though bounded by a nut-shell, I count myself as king of infinite space.”

Charles James Folger, 30 Alb LJ 201, 201 (1884-1885). - The Late Judge Folger, New York Times, Sept. 7, 1884, at 2.

- Browne, Some Characteristics of Charles James Folger, 30 Alb LJ 284, 286 (1885).

- Id.

- Andrews, supra note 8, at 38.

- Id.