This son of a farmer from Albion, New York, having no formal legal education, would live to be the second-longest serving Chief Judge on the Court of Appeals (after now-Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye). His term spanned a decade (all as Chief Judge), and his writings cover 38 volumes of the New York Reports.

Sanford Elias Church was born in Milford, Otsego County, April 18, 1815, the son of Ozias and Permelia Church. In 1835, his family moved to Albion, where he would reside until his death, except for one year in Rochester. His only formal schooling was at Monroe Academy – a boarding school erected in 1826, one of the earliest schools for advanced education in New York. At 19, he began the study of medicine. But his employment as a deputy in the town clerk’s office, where he copied deeds into the deed books, brought him into contact with members of the legal community and led him to abandon medicine for the law. During his apprenticeship with Benjamin R. Bessac, he earned money by working on petit cases in the justice courts. Two years later, in 1840, he became Bessac’s law partner.

At this time, Church was becoming active in Democratic politics. In 1841, he was elected to the State Assembly, a feat for any Democrat in an overwhelmingly Whig district, but particularly for Church, who, at 26, was the youngest member. Despite his age, he was respected and influential, the main voice behind George P. Barker‘s election as Attorney General.

In 1842, Church was admitted to the bar of the Supreme Court of New York. A year later, he associated himself with Noah Davis, Jr.,1 an old friend from the Albion clerk’s office, who was then Presiding Justice of the First Department of the Supreme Court. Their firm, Church and Davis, was one of the most highly esteemed in the state. Upon dissolution of his partnership with Davis in 1857, Church & Sawyer was formed in Albion. About 1862, Church took Judge Henry Rogers Selden‘s2 place in the firm of Selden, Munger & Thompson in Rochester, which became Church, Munger & Cooke. He continued there until he was elected to serve on the Court of Appeals.

Meanwhile, Church became ever more influential in the political arena. In 1845, he was appointed District Attorney of Orleans County. He was one of the original “Barnburners” of the Democratic party. He and Noah Davis, Jr. joined the Free Soil Party and spoke at Free Soil Rallies across the country against the expansion of slavery into the states that were newly forming in the West. However, when the Free Soil Party dissolved upon losing the presidential bid in the 1852 election, Church rejoined the Democrats. During the Civil War, many Barnburners became abolitionists, but Church did not; rather, he spoke of states’ rights and maintaining a solid Union.3 He actively sought volunteers to fight to save the union and when the Orleans County war committee was formed in summer 1862, he was elected chairman.

In 1846 and 1849, respectively, Church was a Democratic candidate for both Congress and the Senate, although unsuccessful. In 1850, however, he was elected Lieutenant-Governor, under Governor Washington Hunt. In 1852, he was reelected to that position, under the Governorship of his friend and fellow Democrat Horatio Seymour. From 1857 through 1859, Church served as State Comptroller and was a delegate to the Democratic National Conventions of 1844, 1860, 1864, and 1868. At the Democratic National Convention held in New York City in July 1868, the New York State delegation chose him as its nominee for the United States presidency; however, Seymour was ultimately nominated to run against Ulysses S. Grant. Church’s name was continually mentioned for the presidency and, in 1874, he was strongly urged to run for Governor. Nevertheless, he refused to seek the nomination, stating that he could not afford it and would not accept campaign money from the Democratic machine.4

In the spring of 1870, Church was nominated by the Democratic Convention for Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, newly formed pursuant to amendments to the judiciary article of the Constitution. Elected by a majority of 87,000, he defeated Henry R. Selden and George F. Comstock, both of whom had been judges on the previous Court. The Associate Judges elected to the bench were William F. Allen (Church’s cousin), Rufus W. Peckham, Martin Grover, Charles J. Folger, Charles A. Rapallo, and Charles Andrews.

Chief Judge Church successfully led the Court through challenging times:

The new Court of Appeals found its task by no means easy; it was called upon to construct a new system of jurisprudence, based on the most radical changes. The Code of Procedure more than once came under judicial condemnation; and the Married Women’s Acts of 1848, 1849, 1860 and 1866 brought many puzzling inquiries before the court. These were followed by many laws permitting parties to be witnesses in their own behalf. Indeed, New York State was pioneering reforms of jurisprudence, and the lot of the judge was not enviable.5

Church wrote several ground-breaking decisions. He and Noah Davis, Jr. would ultimately bring down the New York City Tammany Hall ringmaster William M. “Boss” Tweed. Judge Davis presided over Tweed’s trials on charges of conspiracy, perjury, and larceny. The first trial, conducted in 1873, ended in a hung jury. Tweed was tried again on 220 separate counts and was convicted, but was released after serving one year on the ground that consecutive sentences were impermissible.6 The Legislature subsequently passed chapter 49 of the Laws of 1875, authorizing the State to bring another action. Tweed was ultimately convicted and sentenced to 12 years in prison and fined $12,750. On appeal to the Court of Appeals, Chief Judge Church, writing for the Court, upheld the conviction.7 Boss Tweed escaped in 1875 from the Ludlow Street jail in New York City and fled to Spain. He was caught one year later, while working as a seaman on a Spanish ship, and brought back to New York. Tweed died in debtor’s prison in 1878.

In Manhattan Brass Co. v. Thompson (58 NY 80 [1874]), Chief Judge Church wrote on the right of married women to contract. At that time, single women had the legal capacity to make contracts, to hold property, and to sue and be sued. Married women’s rights, however, were much more limited. In Manhattan Brass, based on the current common law principles, Church upheld the determination of a referee that the plaintiff could not sue Mrs. Thompson for the debts of her husband, even though she had executed a writing saying that she would be responsible for the fulfillment of any contract made by her husband with plaintiff. Chief Judge Church wrote that, although “the facts developed at the trial and found by the referee, present a strong case of moral liability against the [wife] for the payment of this debt[,]” after careful examination, he could not “find a principle within the adjudications which would justify a decision adjudging such liability.”8 He went on to state that, if and when the Legislature changed the common law such that a married woman’s property rights were distinct from those of her husband, and that a married woman could contract the same as an unmarried woman, “it might well be claimed that the rights of married women would have been as well if not better protected practically, sound public policy, and business morality more promoted, and a flood of expensive and vexatious litigation prevented.”9 Eventually, the Legislature passed the Act of 1884, providing that “[a] married woman may contract to the same extent, with like effect and in the same form as if unmarried, and she and her separate estate shall be liable thereon, whether such contract relates to her separate business or estate or otherwise, and in no case shall a charge upon her separate estate be necessary.”10

On May 14, 1880, at age 66, and in seemingly good health, Judge Church died suddenly of unknown causes. Just the day before, he had been writing the opinion in Burr v. Butt Co. (81 NY 175 [1880]). An estimated 6,000 people — including judges, clerks, and reporters of the Court of Appeals — gathered in the small town of Albion for Church’s wake and funeral. Church is buried at the center of Mount Albion Cemetery in Albion, New York. An elaborate marble canopy supported by red granite pillars — a baldacchino — covers his tomb. In Medieval times, baldacchinos of silk and gold thread were held over honored persons and sacred objects.

Upon the Chief Judge’s death, the Court and his chair were draped in black cloth for 30 days. Judge Charles J. Folger, who took over as Chief Judge, gave a speech in Church’s honor, which is published at 77 NY 633. Judge Folger noted that, upon Church’s election to the position of Chief Judge, “[w]hile none doubted his general ability or the purity of his character, it is not too much to say that at the time of his nomination and election, doubts were held by some of the wisdom thereof.” Judge Folger pointed out that Church had no prior judicial experience and was more renowned in politics. However, Folger went on to say:

the ten years of the judicial life of Judge Church have demonstrated that he had in an eminent degree the qualities that fitted him for the duties of his place, and have fully justified the wisdom of his selection. Others who have preceded him on the bench may have had greater and more exact learning in the law. None have excelled him in that equipoise of faculty which enables a judge to fairly weigh and determine causes that come before him. . . . He was not the slave of precedent, fearing to walk in dark places without light from the wisdom of others. . . . The Bar knows that he has led the business of the Court with a kindness of disposition, an evenness and serenity of temper, a gentleness in restraint, a nobleness of courtesy, a patience of hearing to tyro or veteran, that pleased and satisfied and so soothed all as to make even defeat seem half success.

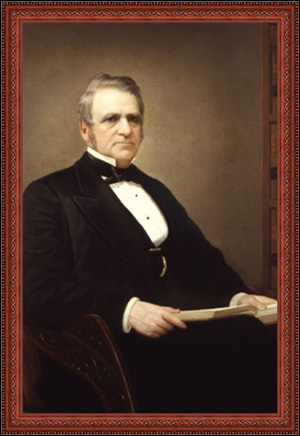

Church was described as a man “of commanding stature, robust physique, and distinguished presence. His head was massive; his countenance strong, sagacious, and benevolent. His manners were not warm nor yet austere, but grave and dignified impressing one with a sense of his sincerity.”11

Progeny

Judge Church was survived by his wife Ann Wild (whom he married in 1840), daughter Nellie, and son George B. His son was an insurance agent, and is thought to have been Superintendent of Insurance for the State. A whole line of Judge Church’s grandsons, however, have been attorneys in Albion. George B.’s son, Sanford T. was admitted to the State bar in 1898; his son, Sanford B., in 1931; and his son, Sanford L., in 1956. Sanford A. Church, Esq., the great, great, great grandson of Judge Church (admitted 1985), is currently an Orleans County Public Defender. He also runs the small town general law practice of Church & Church, which dates back to 1826. The Church’s have been partners in the practice since 1903, when Sanford T. partnered up with a man named Ramsdale. Sanford A. and his father Sanford L. were partners from 1989 through 2000, when Sanford L. retired. According to Sanford A., it remains to be seen whether his fourteen-year-old son, Sanford B., will continue the legal tradition. For the time being, he aspires to be a basketball player.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Alexander, III A Political History of the State of New York (Henry Holt and Co. 1909).

35 Am. L. Reg. 244 (Jan.-Dec. 1887).

Browne, The New York Court of Appeals, Part II, 2 Green Bag 321, 322 (1890).

Chadbourne, Public Service of the State of New York, at 42, available at http://www.courts.state.ny.us/history/elecbook/chadbourne_coa/pg4.htm (accessed July 28, 2005).

Chester, I Legal and Judicial History of New York, at 388-389 (1911).

Freed, Brandes and Weidman, Married Women’s Rights, NYLJ, Feb. 26, 1991, at www.brandeslaw.com/litigationandprocedure/married_womens _rights.htm.

Hampden, Constitutional History of the State of New York, at 202-203 (2d ed 1915).

Harper’s Magazine, October 8, 1870, p. 653 (drawing).

Hastings, I A Treatise on the Law and Practice of Foreclosing Mortgaged Property (1913).

I History of the Bench and Bar of New York, at 279 (Edited by McAdam, et al. 1897).

Hon. Noah Davis, Jr., 66 Albany L.J. 343 (1904-1905).

In Memoriam, 77 NY 633 (1880).

Johnson, Sanford E. Church: Arguably Albion’s most Prominent Citizen, History & Leisure, August 1, 2003.

Law, Politics, and Corruption in New York City, Judge Noah Davis, at http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~cdavis2/noah.html.

Library of Congress, Today in History: December 4, Boss Tweed Escapes!, at http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/today/dec04.html.

Murphy, Biographical Sketches of the State Officers and Members of the Legislature of the State of New York, at 17-21 (1859).

Obituary, An Eminent Jurist Dead, The New York Times, May 15, 1880, at 1.

Obituary, The Dead Jurist, Rochester Daily Union and Advertiser, May 19, 1880.

Obituary, The Orleans American, May 20, 1880.

Our Great Loss, Orleans Republican, May 19, 1880.

Sanford Elias Church, Virtual American Biographies, at http://www.famousamericans.net/sanfordeliaschurch/.

Published Writings Include:

NY Supreme Court: In the Matter of the Petition of the New York Elevated Railroad Company, for Permission to Build a Railroad of Third Avenue, and other Streets of New York (Great Amer. Engraving and Printing Co. 1876).

The Great Need: A City Railroad as a City Work; Rapid Transit for the People at Cost and No Tribute to Monopolies: an Argument, addressed to Property Holders and the People (NY Rapid Tr. Assoc. 1873).

Speech, The Issues Defined! (Watkyns, NY, Aug. 28, 1868).

Canals and State Finances, Remarks delivered at the Convention (Sept. 3, 1867).

Speech, The Issues of the Day; The Revolutionary Designs of the Abolitionists (Batavia, October 13, 1863).

Endnotes

- Noah Davis, Jr., as Justice of the Supreme Court, served ex officio on the Court of Appeals in 1865.

- Henry Rogers Selden (1805-1885) was an Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals from 1862-1865.

- See Speech, The Issues of the Day; The Revolutionary Designs of the Abolitionists (Batavia, October 13, 1863).

- See Johnson, Sanford E. Church: Arguably Albion’s most Prominent Citizen, History & Leisure, August 1, 2003.

- Sullivan, History of New York State, reprinted in There Shall be a Court of Appeals, at 15.

- See People ex rel. Tweed v. Liscomb, 60 NY 559 (1875) (Opn by Allen, J.).

- People v. Tweed, 63 NY 202 (1875).

- Manhattan Brass & Mfrg. Co. v. Thompson, 58 NY 80, 83 (1874).

- Id. at 84-85.

- Laws of 1884, ch. 381, codified as amended at General Obligations Law ‘ 3-301. See Wiltsie, I A Treatise on the Law and Practice of Foreclosing Mortgaged Property ‘ 231, at 344-345 (1913). To the same effect, Chief Judge Church wrote the opinion in Yale v. Dederer (68 NY 329 [1877]) (holding A[i]t is better to adhere to a rule of doubtful property, which has been deliberately settled for a long series of years and repeatedly reiterated by all the courts of the State, than, by overturning it, to weaken the authority of judicial decisions, and render the law fluctuating and uncertain”).

- Browne, The New York Court of Appeals, II The Green Bag, Aug. 1890, at 322.