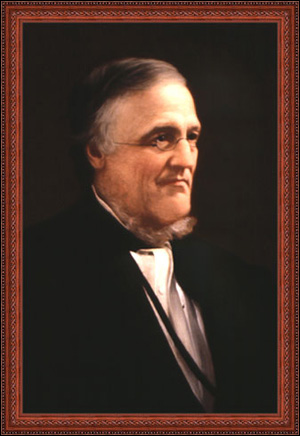

In his 1897 volume Celebrated Trials, Henry Lauren Clinton describes Martin Grover as unique among the judges who have sat on the New York state bench. Grover’s irrepressible humor and distinctive demeanor guarantee him that position for all time.

Martin Grover was born on October 11, 1811, in Laurens (some histories say Hartwick), Ostego County. His father was a farmer of limited means, but “was endowed with that energy of character and unbending integrity that so distinguished his son.”1 Educated at Hartwick Academy, Grover won the commendation of his teachers, who likened his quest for knowledge to “‘a miser seeking for gold.'”2 Grover did not attend college, but studied law with William G. Angel and was admitted to practice at the age of 21.

Some time after 1835, Grover and Angel formed the partnership of Angel & Grover in Angelica, Allegany County. A few years later, Grover formed another kind of partnership-marriage-with Angel’s niece, Emily Whitmore. Angel & Grover was engaged in nearly every important case tried at the Angelica bar.3

As an attorney, Grover “was distinguished more for strength than for polish. He spoke rapidly and used plain, blunt language, but in his efforts before juries he exercised an ingenuity that rarely failed to make an impression.”4 He was dubbed “the ragged lawyer.”5 He wore “square-toed boots to the day of his death, — nicely blackened, to be sure, but that was probably because he could not keep them away from the hotel porter; and broad clothes always sat uneasy and wrinkled upon him, and his trousers were always as short as his temper sometimes was.”6 He was known for coming into court with a wisp of hay in his hair, and “to his last day he had a trick of brushing his head with his hand as he entered court”7-mannerisms likely aimed at winning over rural juries, as he did.

Grover’s intellect was unquestioned. Fellow lawyers admired his extensive legal learning and vast fund of information on subjects such as philosophy, history, biography, metaphysics, statistics, and politics.8 He had a remarkable power of retaining what he learned, and a marvelous grasp of the law’s application to the facts of any given case. That, coupled with his sense of humor, often resulted in stunning courtroom victories.9

Grover, for example, once defended a man accused of murdering his wife by throwing her down a well. The prosecution called a clergyman who testified to attending the wife’s funeral and observing the accused looking across the church and winking at some of girls during the officiating clergyman’s prayers. After Grover’s vigorous cross-examination of the clergyman, the courtroom “convulsed with laughter, and the clergyman left the stand in great rage.” The clergyman then “hissed out at Grover, so as to be heard all over the court-room: You are a gentleman!” Grover replied: “Hold on; go right back on the witness stand. I’ve long wanted a witness I could prove that fact by. But I give you fair notice if you swear I am a gentleman there are a thousand men in Alleghany County, where I live, that will impeach you.”10 Grover’s client was acquitted.

Grover’s years in practice were an excellent prelude for his next career: politics. Widely known as an able debater and an adroit politician,11 in 1844, he was elected to the House of Representatives as a Democrat and served from March 4, 1845 to March 3, 1847. Grover did not, however, adhere to all of the principles of the 19th century Democratic Party, most especially the Party’s support for the extension of slavery in the free territories.

In 1850, Grover officially joined the Republican Party, and in 1853, unsuccessfully ran as the Free-Soil’s candidate for New York Attorney General. During the 1853 political convention, he took an active part in the heated slavery debates, urging “that there is a provision in the Constitution which requires us to surrender slaves, and that, like every other provision, must be faithfully and cheerfully lived up to.”12

As he later explained, “[t]hrough my whole life I have been opposed to the extension of Slavery to Free Territory. I have never doubted the power of Congress to prohibit it in the Territories, and that it was their duty so to exercise that power as to prevent its extension. This doctrine I learned years ago. It was Democratic doctrine,” but now the Democratic Party has announced the direct opposite doctrine as the Party’s fundamental principle.13

In 1857, Grover was elected, as a Republican, to fill a vacancy in the Supreme Court for the Eighth Judicial District14 and in 1859 he was reelected for a full term.

As a Judge, Grover’s character rested “on a granite base,” free of political influence. “In the discharge of his judicial duties, party, politics and friends, were alike forgotten. His integrity was never called in question in his public or private relations.”15 Notwithstanding these accolades, Grover simply could not contain his sense of humor on the bench, and his courtroom was described as a “circus.” There were reports that Grover “was often personal, even to the extent of abuse. He would purposely mispronounce a lawyer’s name to annoy him; ‘Mister Lorrykew,’ for Larocque, is a well known example.”16

In 1859, Grover was designated to serve ex officio on the Court of Appeals. In 1865, he accepted the Democratic nomination for the Court of Appeals, officially switching back to the Democratic Party, a move the New York Times criticized: “The Judge only lowers his own character and proves his unfitness for the Bench, by lending the sanction of his name to the wretched jugglery of the Albany Convention. If the people were fools such a trick might succeed.”17

That same day, the Times published a September 20, 1865 letter of explanation from Grover:

I had differed with some of my associates as to the power and duty of Congress to exclude slavery from the free territories of the Union; that for that cause my political action has, of late years, diverged from that of many of my early associates. That cause of difference is now removed. By the result of the war, slavery is entirely eradicated in the country. . . . That war is now happily and gloriously closed, with a Union preserved and undivided, and human slavery terminated.18

Grover won the 1867 election to the Court of Appeals for an eight-year term and, when the present court was formed under the 1870 Constitution, he was elected for a 14-year term.

As a Court of Appeals Judge, Grover continued his unique style, with some refinement. Notably, he began to dress “with scrupulous care and taste.” He did not, however, have the ability to “sit quietly, look grave, and silently listen to the arguments of Counsel.”19

Given the Court’s heavy backlog, the bench was generally cold, and most Judges did not read the parties’ submissions before oral argument. Grover was the exception. He had a “dreadful habit” of sitting up at night, and reading the record for the next day’s argument.20 Sometimes Grover knew more about the case than counsel, and he thoroughly enjoyed questioning counsel and presenting his own suggestions for the case. The Green Bag editorialized that “[t]he worst of it was that he was usually right; but then he was out of his place, and I doubt that anything was gained for justice by this conduct.”21

Grover helped direct counsel to the asset of brevity, instructing one lawyer that “[t]he court cannot look at all these cases, you know. You pick out three or four that you set the most store by, and we’ll try to look at ’em.” Grover found shrewd ways to worry counsel. He would yawn, or look around and smile (not to say grin) satirically, interrupt, and assume to ‘run the court.'”22 Chief Judge Sanford E. Church was sometimes “visibly amused, sometimes annoyed.”23

The press also picked up on Grover’s dialect, noting that he would tell counsel to address a specific “pint,” rather than “point,” during oral argument. One lawyer attempted to “give [Grover] as good as he sent,” by arguing to the Court “I say, as his Honor, Judge Grover, frequently observes, I don’t think there’s much in that pint.” Grover was “visibly annoyed, and the rest of the judges could hardly conceal their merriment.” Grover had the last laugh, however, as “the court beat him on that very ‘pint.'”24

Astute counsel learned to prepare for Grover’s interruptions. When Grover asked “Where do you get your law?” a young lawyer responded “From the Court of Appeals. Permit me to read a decision handed down by Judge Martin Grover.” Grover rejoined, “That is good law. Keep right on, young man.”25

The bar generally overlooked Grover’s “faults of manner,” and respected him, “because they knew him to be honest, independent, learned, and clear-sighted.”26 His many opinions were concise, straightforward, thoroughly researched and well reasoned.27 Such opinions include Adams v. Perry (43 NY 487), Kinee v. Ford (43 NY 587), Madison Ave. Baptist Church v. Baptist Church (46 NY 131), White v. Howard (46 NY 144), and Clinton v. Myers (46 NY 511).

During the Court’s 1875 summer recess, Grover died at his home in Angelica. His death was “undoubtedly hastened by severe and unremitting judicial labor, carried on with too little regard to health.”28

On August 24, 1875, one day after Grover’s death, the New York Times reported that in the Supreme Court, General Term, Brooklyn, John H. Angell moved that in the memory of Judge Grover, the court should adjourn. Justice Gilbert granted the motion, stating in part:

Many, many Judges of this State have obtained prominence, and among them Judge Grover stands preeminent. His name will go down in history with the names of Kent, Walworth, and others. Judge Grover was a man of conspicuous vigor, clearness of intellect, great scope and breadth of mind, reasonable degree of learning in his profession, and of marked distinctness and uprightness of character, not only as a Judge, but in all the relations of life.29

On September 21, 1875, Court of Appeals Chief Judge Sanford E. Church delivered a memorial to Judge Grover, recognizing both his distinctive character and his extraordinary ability:

No doubt there were shades in his character; there will be when there are great prominences to cast them. He was very real and practical, and hence not pleased with forms, nor observant of conventionalities, or at times of courtesies. . . . There was, however, a well-spring of sympathy and kindness, of which those who know best among his rural neighbors, who have ever found him a ready and unpaid adviser, a discreetly generous helper, a most lenient creditor.

. . .

His rugged constitution and physical frame of power, at last yielded to the silent, weary, unremitted labor, too seldom alternating with the relaxations common with men of less assiduity of pursuit. He died before the measure of his years was full, and with a regretful sense, that there should have yet more time been spared to him, for yet more service. But he has left a noble fame, the record of a life clear and clean in its aims, pure in public ways and private paths, full of busy, useful labors, and of duties well discharged, and crowned with honor.30

Chadbourne’s Public Service of the State of New York echoed these sentiments:

Judge Grover was a man of large professional learning, untiring industry, and an almost unparalleled power of application; of unerring common sense and a keen appreciation of humor; of quick perception and broad comprehension; of sturdy honesty and boldly independent judgment; of a deep love of right and justice and hearty scorn of wrong; holding his opinions with extreme fierceness, but candid and reasonable in spirit; sometimes restive under argument, always patient in investigation; of plain manners and blunt demeanor, sacrificing not to the graces, and but little to the usages of polite society; of robust and massive frame, heavy in movement but not devoid of a single dignity; careless in his dress, unostentatious, democratic. Like Othello, he was rude in speech; like Ulysses, he was subtly wise.31

Grover’s will devised the house, lots, furniture, carriages, harnesses, horse, cow, $5,000 stock in the Angelica bank, and $22,000 cash to his wife. He left $5,000 to his sister-in-law Miss Clara Whitmore (presumably Emily Whitmore Grover’s sister), a gold watch to Martin Grover Whitmore, and $3,100 to his brother Evartus and unnamed sister. Emily Grover died in 1893. The couple had no children.

Judge Grover is buried in Angelica Cemetery in Angelica, New York, with what one imagines to be an eternal smile on his face.

Progeny

Judge Grover and his wife Emily Grover died without leaving any children.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Albany Law Journal, September 25, 1875, at 201.

Albany Law Journal, October 2, 1875, at 219.

Beers History of Allegany County, N.Y., 1806-1879 (F.W. Beers & Co. 1879) (Picture).

Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932 (1985).

Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, Grover, Martin http://bioguide.congress.gov.

Burnham, Leading in Law and Curious in Court (1896).

Chadbourne’s Public Service of the State of New York, available at The Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York website , at 6-7.

Chester, Courts and Lawyers of New York, A History 1609-1925, Vol. III (1925).

Chester, Legal and Judicial History of New York, Vol. II.

Clinton, Celebrated Trials (1897).

Close of the Soft-Shell Convention, New York Daily Times, Sept. 17, 1853, at 3.

Court of Appeals Proceedings, 59 NY 663.

The Democratic State Convention, Special Correspondence, New York Daily Times, Sept. 15, 1853, at 3.

Dougherty, Constitutional History of New York State from the Colonial Period to the Present Time (1911).

Editorial, New York Times, Sept. 29, 1865, at 4.

Google, Find a Grave, Martin Grover judge, http://64.233.161.104.

The Green Bag, Grover, Martin, Biographical Sketch: Vol. 2, 324 (1890).

Harper’s Magazine, October 8, 1870, p. 653 (drawing).

Hartwick History .

10 Ill. L. R. 243 (1915-1916).

Letter, The Democracy of Western New York, New York Daily Times, July 18, 1856, at 3.

Letter, Former President of Historical Society of Allegany County.

Letter, New York Times, Sept. 29, 1865, at 5.

McAdam et al, Editors, History of the Bench and Bar of New York, Vol. I (New York History Company 1897).

New York State Court of Appeals, History, Biographies, Martin Grover http://www.courts.state.ny.us/history/bios/grover_martin.htm.

New York Times, Aug. 24, 1875, at 4.

Official State Canvas, New York Daily Times, Jan. 3, 1854, at 6.

Political, New York Times, Oct. 9, 1857, at 4.

The Political Graveyard: Index to Politicians: Grovenor to Guert,

http://politicalgraveyard.com/bio/grovenor-guert.html.

Proctor, Lawyer and Client; or the Trials and Triumphs of the Bar (1882).

Proctor, The Bench and Bar of New York (1870).

Proctor, The Judges and Lawyers of Livingston County and their Relation to the History of Western New York (1879).

Republican State Convention, New York Times, Sept. 24, 1857, at 1.

Sprague, Flashes of Wit from Bench and Bar (2d ed 1897).

State Affairs, New York Daily Times, Jan. 31, 1857, at 1.

Weed, Revising Constitution in 1867, New York Times, July 11, 1915, at SM11.

Wellman, Gentlemen of the Jury: Reminiscences of Thirty Years at the Bar, New York, 1924, pp. 182-183.

Published Writings

We are not aware of any publications by Judge Grover.

Endnotes

- F.W. Beers & Co., History of Allegany County, N.Y., 1806-1879, at 204.

- Lucien Brock Proctor, The Bench and Bar of New York, at 747 (1870).

- In 1843, Grover & Angel dissolved. Angel thereafter formed a partnership with his son until the elder Angel was elected county judge of Allegany County.

- Beers, at 204.

- Alden Chester, Courts and Lawyers of New York, A History 1609-1925, Vol III, at 1280 (1925).

- The Green Bag, Grover, Martin, Biographical Sketch: Vol 2, at 325 (1890).

- Id.

- Proctor, The Bench and Bar, at 747.

- Clinton, Celebrated Trials, at 288 (1897).

- Id. at 290.

- Beers, at 204-205.

- Close of the Soft-Shell Convention, New York Daily Times, Sept. 17, 1853, at 3.

- Letter, The Democracy of Western New York, New York Daily Times, July 18, 1856, at 3.

- Some reports state that Grover filled a vacancy left by Judge Sill, others that the post was vacated by Judge Mullett.

- Proctor, The Judges and Lawyers of Livingston County, at 13.

- The Green Bag, at 325. The Green Bag also printed the following poem:

“A western New York judge of sterling mental stuff,

Of shaven upper lip, of manners coarse and rough,

Disdaining all such foppery as clean apparel,

Once with a young attorney sought to pick a quarrel,

And with ill-timed severity in court did lash

The offending youth because he sported a moustache, —

Saying, ‘young man, that dirty hair about your mouth

You didn’t wear till you from Buffalo went South,

And left plain folks like us for the metropolis.

The bashful but deserving youth blushed deep at this,

But held his tongue, and bowing low to the rebuke,

Waited till summing up, when thus revenge he took:

‘The point is gentlemen, whether a custom’s provided,

With reference to which these parties are supposed

T’have contracted, — one, ’tis said, to Buffalo

Peculiar and unknown as farther south you go.

Such case may easily be, for from his Honor’s talk

You hear what’s strange to you is common in New York.

With us they let the beard grown on the upper lip

But this subjects one here to a judicial nip.

No custom’s universal, but customs vary

With each degree of latitude in which you tarry;

A New York judge takes pride in keeping free from dirt;

Not so with judges here, — look at his Honor’s shirt!’

The bar, with loud applause greeting this pity one,

Acknowledged Grover met his match in Fithian.” - Editorial, New York Times, Sept. 29, 1865, at 4.

- Letter, New York Times, Sept. 29, 1865, at 5. Grover also expressed his dissatisfaction with the Republican Party’s measures in regard to the war, especially the issue of depreciated currency.

- Clinton, Celebrated Trials, at 291.

- Burnham, Curious in Court, at 119 (quoting 36 Alb. L. J. 2).

- The Green Bag, at 326.

- Id. at 325-326.

- Id. at 326.

- Burnham, Curious in Court, at 119-120.

- Sprague, Flashes of Wit from Bench and Bar, at 15 (2d ed 1897).

- The Green Bag, at 326.

- Id. at 326.

- Chadbourne’s Public Service of the State of New York, at 52.

- New York Times, Aug. 24, 1875, at 4.

- 59 NY 663.

- Chadbourne’s Public Service, at 52-53.