Born Carl Bernard Zanders, Jr., in Apopka, Florida, on April 24, 1926, Fritz Winfred Alexander, II was later given the name of his mother’s brother, a Gary, Indiana, lawyer with whom he went to live after his mother became ill.1 Upon surveying the Judge’s long and illustrious legal career, it becomes apparent that the elder Alexander gifted to his young nephew not only his euphonious name, but also imparted a drive for excellence, an inclination toward public service and social justice, and a passion for the rule of law.

Judge Alexander’s appointment to the Court of Appeals on January 2, 1985 by Governor Mario Cuomo marked a significant milestone in the Court’s history: he was the first Black American to be appointed to a full fourteen-year term on the Court.2 Upon his nomination, the fourteen-member Committee on Judicial Selection of the New York State Bar Association judged him to possess “pre-eminent qualifications” and concluded that he was “well-qualified” for the position of Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals. Although the Judge was keenly aware of historical and social import of his appointment, he was adamant that his paramount allegiance on the Court was to the people of New York and to the rule of law. At his confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee (which voted his nomination unanimously), he acknowledged the “symbolic significance” of his status as the first Black American to be elevated to a full term on the Court of Appeals,3 and upon taking the bench insisted that he was appointed not because of his race, but because he was “a good judicial choice,” and that his paramount role was “to serve the people of this state as a judge of this court.”4 On the occasion of his leaving the Court after only seven years into his term, and four years shy of the mandatory retirement age of 70, he remarked that he most wanted to be known “as a jurist who sought to discharge his responsibilities to the very best of his ability, to serve justice and the rule of law, and about whom it can be said ‘job well done.”5

While Alexander sought to downplay his race, even as a judge he was not immunized from racial prejudice and discrimination. In her memorial remarks after his death in 2000, Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye remembered that the Judge shared personal accounts of his experiences of invidious discrimination “not with bitterness but with clear resolve to effect change.”6 It is not surprising, then, that when confronted by racism from the infamous Ku Klux Klan, Judge Alexander took the incident in stride. Sometime between Friday night, January 16, 1981 and the following Saturday morning, the suite of judges’ chambers on the 17th floor of the Criminal Courts Building at 100 Centre Street in Manhattan was burglarized.” According to the New York Times report, six chambers were invaded, nine typewriters stolen, and “the chambers of a black State Supreme Court justice ransacked and the letters ‘KKK’ scrawled on the walls . . . Only the chambers of Justice Fritz W. Alexander, who is black, were defaced.”7 Characteristically, Judge Alexander didn’t want the incident “blown out of proportion.”8

Undoubtedly Alexander’s attitude in that situation was born of long experience. At age 16, he was the youngest graduate in the 1942 class of the all-Black Theodore Roosevelt High School,9 which had been established in 1927 as a result of the exclusion by whites of Blacks from the Gary high schools.10 After high school he served in the United States Naval Reserve as a quartermaster, 2nd class during World War II, and also during the Korean conflict. As a student at Dartmouth College he participated in officer training from 1944 through 1946, and was enrolled in a selective training module, the “V-12 program,” which was designed to give officer candidates preliminary training during World War II.11

One of only four Black students in the Dartmouth College class of 1947, Alexander excelled academically, socially, and athletically. He majored in government there and was inducted into The Green Key Society, an honorary student service organization charged with service to and leadership in the Dartmouth community.12 He was elected its treasurer in April 1946.13 As a six foot, 200 lb. center on the Dartmouth football team, his “bulk and fight” was credited with bolstering the “middle of the Green line.”14 The team profile described Alexander as “Never one to take a step backward when contact with the ball-carrier is evident.”15 He proved a formidable force in the boxing ring as well, despite having suffered football injuries that would vex him throughout his life. He was Dartmouth’s 1945 heavy-weight champion, albeit by default.16 Given his reputation for facing challenges head-on, one can only imagine Alexander’s disappointment when his opponent, “John Bennett of Hitch” failed to show up for what the Dartmouth Log said “might have been the fight of fights.”17

Alexander maintained close ties with Dartmouth in the years after his graduation. He co-founded the Black Alumni of Dartmouth Association in 1971, and served as its first president (1973-1975).18 Dartmouth was established in 1769 to educate American Indians and had its first Black American graduates in the 1820s, so Alexander felt that the college had formally acknowledged the value of a diverse student population without fully embracing and implementing the idea. No doubt motivated by the isolation he experienced at Dartmouth during the 1940s, he challenged the school to live up to its charter commitment to diversity.19 In his memorial remarks at the Riverside Church in New York City on May 20, 2000, Dartmouth President James Wright recognized Alexander’s role in the fight against racial inequality at the college, saying that “[h]is leadership, his vision, his commitment to basic principles helped Dartmouth through some critical transition years in the 1970s.”20 Alexander was credited with increasing the participation of Black alumnae in recruitment, alumni relations, and with urging the college to integrate diversity, equal opportunity, and affirmative action principles in the life and governance of the school.21 At Alexander’s insistence, Dartmouth College appointed its first black trustee, Harry Dodds.22

After Dartmouth, Alexander studied at New York University Law School and graduated in 1951. Alexander was initiated into the judiciary in October 1970, when New York City Mayor John V. Lindsay appointed him as an interim judge on the city’s Civil Court, and that same year was elected to a ten-year term as a Judge of the Civil Court from the Fifth Municipal Court District. He served as Acting Justice of Supreme Court from time to time between 1972 and 1975, sitting in the Criminal Branch and the Appellate Division, and sat by designation in the Family Court (1974-1975). He also took an academic turn, serving as an Adjunct Professor of Law at Cornell Law School in 1974-75. In 1977, he was appointed to an interim term as a Justice of Supreme Court, and was elected to a full fourteen-year term from the First Judicial District with the backing of the Democratic and Liberal parties. In 1982, the Governor designated him to sit as an Associate Justice of the Appellate Division, First Department. With his appointment to the Court of Appeals in 1985, he filled the seat left open when Judge Hugh R. Jones retired.

By 1992, Alexander had established a reputation for his deliberative approach to jurisprudence, his strong commitment to individual rights, and for the “three-alarm” chili which he occasionally cooked up for other judges.23 That year, just four years shy of the Court of Appeal’s mandatory retirement age, and seemingly at the pinnacle of his career, Alexander stunned many of his colleagues and friends when he voluntarily left the Court to join the administration of his New York University School of Law classmate and former law partner, David Norman Dinkins, the first African-American mayor of the City of New York. 24 In a move that “took the legal community by surprise,”25 Alexander left behind what he described as “the relative tranquility of the Court” 26 for New York City’s chaotic criminal justice system to take on what one reporter described as “a relentlessly fractious criminal-justice system as a bureaucratic traffic cop, mayoral troubleshooter, and (on occasion) interagency mud-wrestling referee.”27 According to New York Newsday, Alexander’s toughest task in his new job would be “forcing a bloated NYPD to shoo more cops out from behind desks and onto the streets.”28 Not surprisingly, “many were critical of his choice. They saw it as folly, a step in the wrong direction.”29 Even Dinkins himself said that he was surprised when Alexander accepted the thankless job of overseeing the city’s Police, Fire, Correction and Probation departments.30

While his decision to leave one of the nation’s most prestigious legal positions at the height of his career confounded many of his colleagues, the move was consistent with his well-established commitment to family and friendship, and his penchant for confronting important challenges. A year into the job, Alexander expressed no regrets about his decision, and explained that it was “home and friendship” and the challenge of the job, that led him to step down from the bench,31 as well as a longing for something different after twenty-two years as a judge.32 The opportunity to assist his longtime friend David Dinkins, to help his beloved New York City through its fiscal and civil woes, along with the chance to be closer to home and to his wife, Beverly, apparently was an irresistible combination.

Then-Chief Judge Sol Wachtler apparently had mixed emotions about the move. At the official ceremony at the Court marking Alexander’s departure, Wachtler observed that “[t]he choice he made to relinquish his seat on this Court and to accept a new responsibility speaks eloquently of Judge Alexander’s character. It tells us about his loyalty to friends, his dedication to the people of the City he loves and his willingness to confront any challenge.”33 A few months later, though, he took a different view in a speech before the Legislative Correspondents Association, derisively quipping that “[i]f he [Judge Alexander] follows the trajectory, his next job will be school crossing guard.”34

In addition to the challenge of the job and the opportunity to spend more time with his family, Alexander made it clear that his long standing and close association with former classmate and law partner, Mayor Dinkins played a decisive role in his decision to accept the post. Calling Mayor Dinkins his “very dear friend,” Alexander said “I love the City of New York . . . [t]he Mayor needed someone to fill this spot . . . and I’ve always been at his side in situations where I could be of help to him. So here I am.”35 He and Dinkins had been students together at New York University School of Law, where he served on the Moot Court Board, as president of his class and vice-president of the Student Bar Association.36 Dinkins and Alexander had lived in the same apartment building in the 1950s “the Riverton Apartments in Harlem”.37 After working for a time with the law firm of Demov, Morris, Levin & Hammerling following his admission to the New York State bar in 1952, Alexander joined Dinkins and Thomas Benjamin Dyett in 1958 to form Dyett, Alexander & Dinkins, “the leading black law firm in New York City in its day.”38 The firm, with which Alexander was affiliated until 1970, served a largely black clientele39 and also represented institutional clients such as the United Mutual Life Insurance Company and Allied Federal Savings and Loan in Queens, New York.40 In 1965, as a member of the influential Carver Democratic Club in Harlem, Alexander helped coordinate Dinkins’ upset state assembly victory.41 Along with the likes of other influential Black American men such as United Nations Ambassador Ralph Bunche, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., federal appeals court judge A. Leon Higginbotham, Bill Cosby, and Jesse Jackson, Alexander and Dinkins were fellow members of Sigma Phi Pi, the oldest Black Greek letter fraternity in the United States. Described by the Washington Post as a “once-secret black fraternity that celebrates the professional and material success of black men,” the New York chapter of the organization, popularly known as the Boule, was founded by W.E.B. DuBois.42

As Deputy Mayor, the Judge helped steer Dinkins through a series of fiscal and civil crisis plaguing New York City at that time, and was at the center of all the major decisions of the Dinkins administration. He was a steadfast backer of Dinkins, as illustrated by an editorial he wrote in 1992 in which he defended Dinkins against charges that he took sides against the police after the death of a young Hispanic man during a confrontation with police officers. In a letter to the editor of the New York Times, Alexander charged opponents of Dinkins with “concocting ever more fantastic tales about the events surrounding the Washington Heights disturbances that followed the death of Jose Garcia last month,” and maintained that “[t]o suggest that comforting Mr. Garcia’s family was to ‘take sides’ against the police . . . spins a fantasy that only encourages dissension and, worse, risks further violence.”43

On the Court: A Centrist, and Champion of Individual Rights

Although Judge Alexander balked at the appellation, he was widely perceived as a centrist, albeit with liberal leanings. A relatively infrequent dissenter, Judge Alexander wrote 108 majority opinions, 18 dissents, and two concurrences during his tenure on the Court. Hailed by many as a “champion of individual rights” and of the rights of the accused, he refused to pigeonhole his judicial decision-making. Of his jurisprudential approach, he said: “I never tried to categorize myself. I call them as I see them.”44 Court watchers concurred, and described Alexander’s approach as “very fact-specific,” characterized by “a pragmatic dedication to justice on a case by case basis,” not dictated by a personal judicial agenda45 or an “overarching judicial philosophy.”46 Research conducted by the New York Law Journal and other organizations illustrate his “middle-of-the road” jurisprudence:

“During nearly seven years on the bench, Judge Alexander wrote opinions in 44 criminal cases, with 21 rulings favoring prosecution and 23 the defense. Of Judge Alexander’s 27 writings in the tort field, the breakdown was 10 favoring plaintiffs and 17, defendants . . . [s]tatistics kept by the Bronx District Attorney’s Office show that in close to 160 criminal cases decided since September 1990, Judge Alexander has ruled almost evenly for the prosecution and defense. In state constitutional cases, Judge Alexander aligned evenly with each side in 32 cases that have split the court since the start of 1990.”47

Judge Alexander’s role as a “swing-vote” is suggested by an analysis of 12 cases in which the Court was divided between prosecution and defense. In 10 of those cases, he aligned with the defense, and a Legal Aid survey of cases where the Court divided in either memoranda or opinions in 1990 and 1991 found that Judge Alexander voted for the defense in 29 of 43 cases studied.48

Despite his frequent alignment with the defense in criminal cases, in People v. Kern, 75 N.Y.2d 638 (1990), writing for a unanimous Court Judge Alexander held that, like the prosecution, defendants have no right to use peremptory challenges in a racially discriminatory manner to exclude persons of a particular race from service on a criminal jury. The case arose from the highly publicized “Howard Beach incident,” in which the defendants were convicted of manslaughter for their participation in an attack by a group of white teen-agers upon three black men in the community of Howard Beach in Queens, New York. The attack occurred during the early morning hours of December 20, 1986, after the three victims left their disabled car on the nearby Cross Bay Boulevard and walked into the Howard Beach neighborhood to seek assistance. The Judge wrote that “such racial discrimination has no place in our courtrooms and that such conduct by defense counsel is prohibited by both the Civil Rights Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of our State Constitution.” He rejected the position, supported in an amicus brief by the Legal Aid Society that “[t]he antidiscrimination clause of the State equal protection provision is inapplicable to the use of peremptory challenges by criminal defendants and their attorneys”49 Looking at the issue from the societal perspective rather than from the perspective of the accused, he stressed “the rights both of the excluded jurors and the community-at-large,”50 and reasoned that “[r]acial discrimination in the selection of juries harms the excluded juror by denying this opportunity to participate in the administration of justice, and it harms society by impairing the integrity of the criminal trial process.”51

Judge Alexander’s individualist libertarian inclination is probably best represented by the opinion he wrote in the case of Rivers v. Katz,52 67 NY2d 485 (1986), in which the Court reviewed the scope of the State’s authority to forcibly administer antipsychotic drugs to individuals involuntarily committed to state facilities. Concluding that the Due Process Clause of the New York State Constitution protects the common law right of individuals who are mentally ill to make treatment decisions for themselves, and that the State may not forcibly administer antipsychotic drugs to a patient in a mental health facility over the patient’s objection, Judge Alexander elegantly observed that:

In our system of free government, where notions of individual autonomy and free choice are cherished, it is the individual who must have the final say in respect to decisions regarding . . . medical treatment in order to insure that the greatest possible protection is accorded with the furtherance of his own desires. This right extends equally to mentally ill persons who are not to be treated as persons of lesser status or dignity because of their illness.”53

Other opinions of note penned by Judge Alexander include a dissent in which he argued that prison officials had violated the privacy rights of a prisoner by banning him from participating in a program allowing conjugal visits after it was discovered that the prisoner had AIDS;54 and a majority decision which rejected claims by the Mercury Bay Boating Club of New Zealand that the deed of trust for the America’s Cup sailing competition barred the San Diego Yacht Club from using a catamaran, a boat that was inherently faster than the monohull used by the New Zealanders.55 The New Zealand challengers had argued that the catamaran made a mockery of the race, and that the competition was a “gross mismatch” because multihulled vessels were so much faster than monohulls.56 Judge Alexander, writing for a 5-2 majority, concluded that the San Diego team was the rightful recipient of the 139-year-old silver trophy because “nothing in the deed [of trust] limit[ed] the design of the defending club’s vessel.”57 Thus ended a three-year legal battle over the yachting world’s most renowned prize.

Both the bench and the bar considered Alexander to be the consummate jurist: meticulous, pragmatic, and eminently collegial. He was described as “perceptive and thorough on the bench, warm and sociable off, with a sense of humor that belied his sometimes formal bearing.”58 He was valued by Judge Wachtler as “an intelligent, articulate legal thinker” and “a man of sensitivity and compassion,”59 while Judge Kaye saw him as “consummately collegial, respectful, good-humored.” Kaye observed that “[t]he only thing I can ever recall about Fritz Alexander that was even close to sharp was his ‘three-alarm chili’ that he often threatened to, and sometimes actually did, produce.”60 In a “Letter to the Editor” to the New York Law Journal on the occasion of his passing, Michael Letwin and Mitchell J. Briskey, president and vice president for criminal appeals, respectively, of the Association of Legal Aid Lawyers, UAW, local 2325 wrote:

[T]he historical significance of his path-breaking career speaks for itself. He opened doors through which many shall one day pass; his contribution to opening the New York bar and judiciary to people of color will not be forgotten. We are writing to note particularly that he was a rare judge who never lost sight of our client’s essential humanity no matter how horrid the crimes for which they were convicted. While we differed on many occasions, he was a person of principle who did not lose his heart as he found success. Judge Alexander unfailingly treated our lawyers with respect. He encouraged our public service and supported advocacy on behalf of the downtrodden and despised. We hope to someday encounter a judge of his historic achievement and undiluted humanity again. In the meantime, he will be missed.61

After the Court

Despite Judge Wachtler’s sardonic prediction about the Judge’s future prospects upon his premature departure from the Court, Alexander continued to be active in the legal profession and in the civic life of the State and City of New York after leaving city administration in the wake of Dinkins’ failed reelection bid in 1993. Among other important post-Dinkins positions, he was appointed in 1994 as a Distinguished Jurist-In-Residence at his alma mater, New York University School of Law, and that same year joined Epstein Becker & Green in Manhattan as special counsel, where he focused on litigation matters.62 By appointment of then Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye, he chaired the Commission on Alternatives to Incarceration charged with considering alternative sanctions for nonviolent offenders in New York. That commission released a report proposing that prosecutors not be allowed to block a judge from sentencing nonviolent drug offenders to a state-sponsored drug treatment program.63

Despite his exemplary record, Judge Alexander’s professional life after the Court was not without some controversy. In 1996, the Judge became embroiled in a dispute over a $350,000.00 commission he was awarded for serving as a court-appointed receiver in a $62 million dollar real estate foreclosure action in the case of Bank of Tokyo v. Urban Food Malls (650 NYS 2d 654) (1996). Lawyers for Urban Food Malls attempted to oust Alexander after it was discovered that he had had a brief romantic involvement in the 1970s with the judge who had appointed him as receiver in the case, Judge Jane S. Solomon. The lawyers also sought Judge Solomon’s recusal, claiming that she had not been candid when she appointed Alexander to collect five million dollars in rent owed by the defendants to the Bank of Tokyo. Ethics experts observed that nothing in the Code of Judicial Ethics barred judges from appointing receivers who are close friends or who dated in the past, and the Appellate Division, First Department found no legal reason for Judge Solomon’s recusal, and as to the issue of Judge Alexander’s disqualification, that there was “no basis, legal or factual, to remove Mr. Alexander as receiver. The claims of impropriety and appearance of impropriety are completely unsupported.”64 Although Judge Solomon eventually relinquished the case after initially refusing to do so, during the recusal hearing she insisted that the long-past relationship was “irrelevant,” and that she had not been in contact with Alexander for a decade. She is reported to have said that “By the time he and his wife invited me to the wedding, he was an old friend. It was history.”65 The Appellate Division agreed, stating that “there clearly was no legal basis for recusal.”66 The court noted that the “long-past romantic relationship between the Justice and Mr. Alexander (neither of whom, incidentally, was married at the time). . . . does not constitute a ground for disqualification or trigger any disclosure requirements.”67 As receiver, Alexander was entitled to keep up to 5% of all rents and fees collected, and, although the disputed $350,000 fee was less than the maximum amount allowed under state law, according to the office of court administration it was higher than any single commission earned by a receiver in NYC that year.68

This incident was a minor flap in an exemplary career that spanned four decades. Over the course of his professional life, Judge Alexander was affiliated with numerous professional organizations, including the American Bar Association, the National Bar Association (a Black lawyers’ group that encourages young Blacks to enter the law (founding member), the Metropolitan Black Bar Association, the New York State Bar Association, the American Judicature Society, and the Advisory Committee of the Center for Judicial Conduct Organizations of the American Judicature Society. He was Vice President of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York and served on the Association’s Lectures and Continuing Education committee and its Centennial Study on Decentralization in Government in New York City. He was Trustee of New York University Law Center Foundation, a member of the Board of Trustees of New York University, and a Director of the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. He received numerous awards, including honorary doctor of law degrees from the law schools at Pace University, the State University at Albany, the College of New Rochelle, and Long Island University. He was an honorary member of the Order of the Coif, and, in addition to numerous awards from professional, civic, and community organizations he received the Golda Meir Memorial Award from the Jewish Lawyers Guild; the Arthur T. Vanderbilt Gold Medal, the highest honor awarded by New York University School of Law; and the Wm. A. Hastie Award from the Judicial Council of the National Bar Association. Alexander served as president of the Harlem Lawyers Association, was a founding member of 100 Black Men, Inc., a member of the Board of Directors of Harlem Neighborhoods Association, Inc., former director and executive vice president of United Mutual Life Insurance Company, member of Board of Managers and Treasurer of United Charities, and served on the Board of Directors of New York City Mission Society.

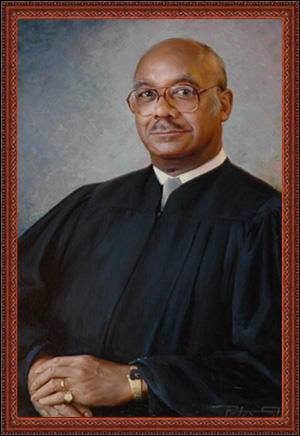

As fate would have it, on April 8, 2000, less than two weeks before he succumbed to cancer and just two days before his 74th birthday, the Black, Latino, Asian, & Pacific American Law Alumni Association (BLAPA) of New York University School of Law honored Judge Alexander and his life’s work at its annual dinner party. Judge Kaye remembers that on that occasion at their mutual alma mater, Alexander was surrounded by a diverse group of students, “beaming with pride and choked with emotion at the personal, institutional and societal progress that ceremony represented.” Judge Alexander’s portrait, which was unveiled at that ceremony, now graces the walls of the law school’s library. The law school also established a scholarship in his name, the Alexander Fellows, designed to help recent graduates who want to pursue careers in law teaching to prepare for the teaching market.

Although the breadth and depth of this life lived in the law can barely be summed up in words, Judge Judith Kaye perhaps captured its essence when she said that (by any measure Fritz Alexander’s life was important, meaningful, well lived “a path-breaking career; a champion of American justice; a learned, sound, caring jurist; a much-loved husband, father and grandfather; a cherished colleague and friend.” 69

Indeed.

Progeny

Judge Alexander was survived by two daughters and a son. Karen Alexander-Harris, currently President of the New Jersey Cable Telecommunications Association, is a graduate of Brown University and a specialist in energy, environmental and telecommunications. Kelly Alexander Carbonneau lives with her husband Mike and daughter Danielle in the Caribbean isle of St. Maarten, where they operate a car rental company. Fritz the III, a resident of suburban Atlanta, works in the facilities management field, currently managing support operations for the law firm of Womble Carlyle Sandridge and Rice.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Published Writings Include:

‘Frost Finds Satisfaction in Army’s Caste System Report,’ The Dartmouth (May 31, 1946).

‘Hold Funeral Services for Dean Strong This Afternoon at 4.30 as College Mourns,’ The Dartmouth (June 10, 1946).

‘Duke Promises Variety of Selections Tomorrow Night,’ The Dartmouth (May 3, 1948).

‘Peace and Provocation in New York City,’ Editorial, New York Times, Aug. 12, 1992.

‘Tribute to Judge Kaye,’ New York University Annual Survey of American Law, xxix (1994).

Sources Consulted

Alumni Profile, Career Ladder Takes Judge Alexander To New York’s Highest Court, New York University Law School Magazine, Fall 1985, at 9.

Baker, Black Fraternal Groups Play Big Role in Funding Wilder’s Presidential Bid; Candidate Makes Use of Untapped Exclusive Middle-Class Clubs, Washington Post, Nov. 23, 1991, at A4.

Bates, Elite Fraternity Widens Agenda for Black Men Organizations: At the Prompting of a Younger Generation Prosperous and Prominent Members of the Once-secret Boule are Focusing More on Social Activism, Los Angeles Times, July 18, 1990, at E1.

Carroll, et al., Dinkins Scores with Fire Dept., NY Newsday, June 12, 1992, at 20.

Chambers of Black Judge Defaced During Break-In, NY Times, Jan. 18, 1981.

Feehan, Catherine & Karnis, Elisa, Is There High Ground In the Middle of the Road? A Review and Analysis of the Jurisprudence of the Honorable Fritz W. Alexander II, 8 St. John’s J. Legal Comment. 531(1993).

Goldstein, Judges’ Prior Relationship Impacts Case, NY Law Journal, May 1, 1996, at 1.

Goldstein, OCA Announces Plan to Speed Criminal Cases, NY Law Journal, Dec. 4, 1996, at 1.

Goldstein, No Ethical Lapse Found By Trial Judge, Receiver, NY Law Journal, Dec. 5, 1996.

Green Key Society website, Dartmouth College, http://www.dartmouth.edu/%7Egreenkey/who.html (last accessed August 15, 2005).

Letwin & Briskey, Letter to the Editor: Judge Alexander Remembered, NY Law Journal, Apr. 27, 2000 at 2.

NY Law Journal, Today’s News: Update, May 24, 1994; Feb. 24, 1997.

New York University School of Law, News, Events and Calendars, Faculty Archived News, http://www.law.nyu.edu/newscalendars/ (accessed August 1, 2005).

Obituary Notices, New York Times, April 25, 2000; NY Law Journal, April 25, 2000; NY Times, April 26, 2000; Albany Times Union (NY), April 27, 2000.

Remarks of Sol Wachtler, Chief Judge, State of New York at Ceremony Marking the Departure of Associate Judge Fritz W. Alexander, II, 79 NY2d ix (March 24, 1992)

Remarks of Judge Alexander Upon Leaving the Court, 79 N.Y.2d xi (March 24, 1992).

Remarks of Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye in Reference to the Death of Honorable Fritz W. Alexander, II, 94 N.Y.2d vii (May 2, 2000).

Remarks by President James Wright, Dartmouth College, Memorial Service for Fritz Alexander, at Riverside Church, New York City ( May 20, 2000 (copy courtesy of the Raumer Collection, Dartmouth College.)

Sack, Alexander’s Departure Leaves Cuomo Tricky Task of Picking a New Judge, NY Times, Feb. 9, 1992, at 36.

Senate Confirms Judge Alexander, NY Times, Jan. 30, 1985, at B2.

Spencer, Commission Gears Up To Screen Candidates for Court of Appeals, NY Law Journal, Feb. 10, 1992, at 1.

Spencer, Agreement Reached on Courts Bond Issue: $472 Million to Finance 8 Major Projects, NY Law Journal, Mar. 10, 1993.

The Dartmouth, May 25, 1945; Sept. 28, 1945.

‘This Far By Faith: Black Hoosier Heritage: Education and the Professions,’ Indiana Humanities Council, http://www.indianahumanities.org/thisfar.htm (accessed October 15, 2005).

United Press International (UPI), Alexander Confirmed for Appeals Court, Jan. 29, 1985.

Viewpoints: Into the Trenches: Can he improve public safety?, NY Newsday, Feb. 11, 1992, at 44.

Wilkerson, Two Court Appointees From Different Backgrounds: Fritz Winfred Alexander 2d, NY Times, Jan. 30, 1985, at B6.

Wise, Wachtler Court at 5: Panel Defies Labels, But Individual Trends Emerge, NY Law Journal, Jan. 21, 1992, at 1.

Wise, New York State Court of Appeals: Special Report 1991-92. The Constitutional Balance: No Drastic Shift Seen With New Judge ‘ Alexander, Smith Views Compared, NY Law Journal, Nov. 2, 1992, at S2.

Endnotes

-

The details of Judge Alexander’s early life and legal career are taken generally from various sources, including AMERICAN BENCH (Marie T. Hough et al. eds., 6th ed. 1991-92) and various news articles and obituary notices cited above (‘Sources Consulted’). For a detailed analysis of the Judge’s jurisprudence see Catherine M. Feehan & Elisa Karnis, Is There High Ground In The Middle of the Road? A Review and Analysis of the Jurisprudence of the Honorable Fritz W. Alexander II, * St. John’s J. Legal Comment 531 (1993).

-

Harold Stevens had been appointed to the court in 1974 to fill a vacancy for one year (at the time, Judges of the Court of Appeal were elected, and Stevens’ run for the spot was unsuccessful). United Press International (UPI), Alexander Confirmed for Appeals Court, Jan. 29, 1985 (hereafter Alexander Confirmed).

-

At the time of Judge Alexander’s appointment he told the Senate Judiciary committee: “I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge the symbolic significance of my elevation to the Court of Appeals.” ‘Senate Confirms Judge Alexander,’ NY Times, Jan. 30, 1985. While he expressed hope that he could serve as an inspiration, especially to “the minority youth who so desperately need to be made to feel that there is a real future for them” ‘Alexander Confirmed,’ supra note 2, he nevertheless emphasized his belief that he had not been nominated “because [he] was black but rather because [he] was a good judicial choice.” Isabel Wilkerson, ‘2 Court Appointees from Different Backgrounds: Fritz Winfred Alexander 2d,’ NY Times, Jan. 3, 1985 (hereafter Different Backgrounds). “The fact that I am black is an accident of birth. I am here to serve the people of the state as a judge of this court.” Id.

-

Different Backgrounds, supra note 3.

-

Judge Alexander Remarks Upon Leaving the Court, 79 N.Y.2d ix, x (1992) (hereafter Judge Alexander Remarks on Leaving).

-

Remarks of Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye In Reference to the Death of Honorable Fritz W. Alexander, II, 94 N.Y.2d vii, viii (May 2, 2000) (hereafter Judge Kaye Memorial Remarks); Obituary, NY Law Journal, Apr. 25, 2000.

-

‘Chambers of Black Judge Defaced During Break-In,’ NY Times, Jan. 18, 1981.

-

Id.

-

GaryOnline, http://www.garyin.com/obit/2000/2000%2OBITUARIES_1page4.html (last accessed Feb. 20, 2006).

-

‘This Far By Faith: Black Hoosier Heritage: Education and the Professions,’ Indiana Humanities Council, http://www.indianahumanities.org/thisfar.htm (last accessed Oct. 15, 2005).

-

E-mail correspondence with Sarah Hartwell, Reading Room Supervisor, Raumer Special Collections Library: Archives, Manuscripts, Rare Books, Dartmouth College (Aug. 11, 2005) (on file with the author) (hereafter Hartwell e-mail). For information about the ‘V-12’ program at Dartmouth see http://www.dartmouth.edu/~library/Library_Bulletin/Aprl1999/King.html.

-

Green Key Society website, http://www.dartmouth.edu/%7Egreenkey/who.html.

-

Correspondence with Hartwell (see note 12), Aug. 15, 2006 (on file with the author).

-

The Dartmouth, Sept. 28, 1945.

-

Remarks by President James Wright, Dartmouth College, At the Memorial Service for Fritz Alexander, ’47, Riverside Church, New York City ‘ May 20, 2000 (copy on file with the author courtesy of the Raumer Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College) (hereafter James Wright Remarks).

-

The Dartmouth, May 25, 1945.

-

Id.

-

James Wright Remarks, supra note 15.

-

Id.

-

Id.

21 Id. President Wright noted that Judge Alexander ‘assumed a pivotal role in negotiations with the Dartmouth College administration during the early seventies to advance the cause and increase the involvement of the African-American community of students and alumni in the life of the College. That involvement resulted in the establishment of the Black Alumni of Dartmouth Association as a formal organization, recognized by the College in 1971. Fritz was elected as its first President.’ -

Id.

-

Judge Kaye Memorial Remarks, supra note 6.

-

Feehan & Karnis observe that ‘[w]hen Judge Alexander decided to retire from the bench, many were critical of his choice. They saw it as folly, a step in the wrong direction.’ Feehan & Karnis, supra note 1, at 559.

-

Spencer, Commission Gears Up To Screen Candidates for Court of Appeals, NY Law Journal, Apr. 6, 1992 (hereafter Commission Gears Up).

-

Judge Alexander Remarks on Leaving, supra note 5.

-

Viewpoints: Into the Trenches: Can he improve public safety?, NY Newsday, Feb. 11, 1992.

-

Id.

-

Feehan & Garnis, supra note 24 at 559.

-

Newman, Fritz Alexander II, 73, Judge Who Became a Deputy Mayor, NY Times, Apr. 25, 2000, at B8 (hereafter Newman Obit.).

-

Commission Gears Up, supra note 25.

-

Feehan & Karnis, supra note 1, at note 4 (citing Feb. 22, 1993 interview with Alexander in New York, New York).

-

Remarks of Sol Wachtler, Chief Judge, State of New York at Ceremony Marking the Departure of Associate Judge Fritz W. Alexander II, 79 N.Y.2d ix (March 24, 1992) (hereafter Judge Wachtler Remarks).

-

Carroll et al, Dinkins Scores With Fire Dept., NY Newsday, June 12, 1992.

-

Commission Gears Up, supra note 25. Alexander described his decision this way: ‘The answer is too complex for even me to understand. Part of it is David Dinkins, who is striving mightily to bring the City he and I love through these days of fiscal difficulty; a part of it is the City I have come to love that must survive these difficult times; a part of it is a sense that these times are historic, even if troubled, and an era of which I want to be a part. Ever since David’s election I have had the sense that I should be a player, a member of his team . . . Some people say that I am joining a losing cause, but I don’t believe that. Some say that the City is finished, and that it cannot recover from its fiscal woes, and I don’t believe that either. And while I have no delusions about the job, apparently Mayor Dinkins believes that I can help him and make a contribution. Be assured that I shall do my utmost.’ Judge Alexander Remarks On Leaving, supra note 5.

-

Newman Obit., supra note 30.

-

Id.

-

Feehan & Karnis, supra note 1.

-

Id.

-

Newman Obit., supra note 30.

-

Id.

-

See Bates, Elite Fraternity Widens Agenda for Black Men Organizations: At the prompting of a younger generation prosperous and prominent members of the once-secret Boule are focusing more on social activism, Los Angeles Times, Part E, (July 18, 1990) and Baker, Black Fraternal Groups Play Big Role in Funding Wilder’s Presidential Bid; Candidate Makes Use of Untapped Exclusive Middle-Class Clubs, The Washington Post (Nov. 23, 1991).

-

Alexander, Peace and Provocation in New York City, NY Times, Aug. 12, 1992 (Editorial Desk).

-

Feehan & Karnis, supra note 1 at 558.

-

Id.

-

Wise, New York State Court of Appeals: Special Report 1991-92: The Constitutional Balance: No Drastic Shift Seen With New Judge – Alexander, Smith Views Compared, NY Law Journal at S2, col. 3, (Nov. 2, 1992) (hereafter ‘Views Compared’).

-

Id..

-

Wise, Wachtler Court at 5: Panel Defies Labels, But Indiviual Trends Emerge, NY Law Journal, Jan. 21, 1992, at 1.

-

75 N.Y. 2d at 638.

-

Id. at 654.

-

Id. at 652.

-

67 N.Y.2d 485 (1986).

-

Id. at 493.

-

Matter of Doe v. Coughlin, 71 NY2d 48 (1987).

-

Mercury Bay Boating Club v. San Diego Yacht Club, 76 NY2d 256 (1990).

-

Id. at 259.

-

Id. at 261.

-

Newman Obit., supra note 30.

-

Judge Wachtler Remarks, supra note 33.

-

Judge Kaye Memorial Remarks, supra note 6.

-

Michael Letwin & Mitchell J. Briskey, Letter to the Editor: Judge Alexander Remembered, NY Law Journal, Apr. 27, 2000, at 2.

-

Today’s News: Updates, NY Law Journal, May 24, 1994.

-

See generally Today’s News: Updates, NY Law Journal, Nov. 16, 1994 and Dec. 4, 1996.

-

229 A.D.2d at 17.

-

Goldstein, Judges’ Prior Relationship Impacts Case, NY Law Journal, May 1, 1996, at 1 (hereafter Judges’ Prior Relationship).

-

229 A.D.2d at 26.

-

Judges’ Prior Relationship, supra note 65.

-

Id. According to the NY York Law Journal article, the failure of Justice Solomon to disclose the relationship when she appointed Judge Alexander in June 1995 ‘had raised questions about the obligation of judges when their private and public lives collide.’ Id. The Appellate Court ultimately concluded that allegations that either judge acted improperly was ‘spurious’ and ‘totally meritless.’ Id.

-

Judge Kaye Remarks, supra note 6.

Comments · 1