In Cron v. Hargro Fabrics (91 NY2d 362, 368 [1998]), the Court of Appeals held that the plaintiff’s full “performance of her obligations under the contract within a year is insufficient to take the oral contract out of the statute . . . and we decline plaintiff’s invitation to hold her unilateral performance sufficient to do so.” For this proposition the Court cited, among other cases, Broadwell v. Getman (2 Denio 87 [1846]). Denio Reports continue to appear from time to time, well worn but still useful after a century and a half.

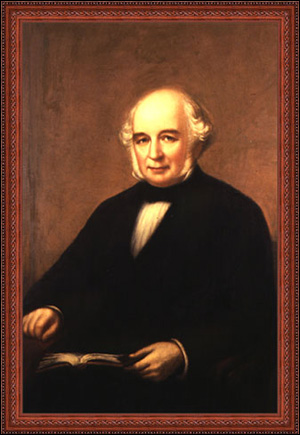

Denio published five volumes of case reports, mostly from the Supreme Court of Judicature, which preceded the creation of the New York Court of Appeals. In 1853, he became a Judge of the Court and served for 13 years, twice as Chief Judge. According to the 1911 Legal and Judicial History of New York, “Judge Denio was an almost ideal judge, and scarcely anyone who ever sat in our court of last resort served the state better than he. His opinions rank with the foremost that were ever written in any court in the entire country.”1 Indeed, few people have achieved so constant a presence in our court system.

Hiram Denio (pronounced Da-NIGH-o) was born in Rome, New York, on May 21, 1799, the third son of Israel Denio, a Revolutionary War veteran. His grandfather, Aaron Denio, was from Deerfield, Massachusetts and fought in the French and Indian War. The family is a mixture of English and French Canadian ancestry.

An Early Star

Judge Denio received his schooling at the Fairfield Academy in Fairfield, New York, located in Herkimer County, and began studying for the practice of law at age 17 with Judge Joshua Hathaway in Rome. He also received legal training in Whitesboro from Henry R. Storrs, whom Senator Henry Clay pronounced “the most eloquent man he ever listened to.”2 Upon admission to the bar in 1821, Judge Denio established a private practice in Rome, a thriving community situated on the soon to be finished Erie Canal. While in Rome, he was appointed Oneida County District Attorney, and served in that capacity from 1825 to 1833.

As District Attorney, Judge Denio moved his office from the northern county seat, Rome, to the southern county seat, Utica. Judge Ward Hunt later observed that:

in every criminal case, he was thoroughly prepared, both on the law and the facts. His indictments were accurately drawn, and always stood the test of criticism. He tried his cases with zeal and vigor. Indeed it was sometimes said that he sought convictions with too much earnestness. But he never asked a conviction unless satisfied of a prisoner’s guilt. Being so satisfied, he seldom failed to impress his conviction upon the jury. Culprits complained, but the public were content.3

In 1829, he married Mary Ann H. Pitkin of Farmington, Connecticut, with whom he had three children-Mary, Elizabeth and a son who died in infancy. During his tenure as District Attorney, Judge Denio was also engaged in private practice in Utica with E. A. Wetmore.

In 1834, he was appointed Circuit Judge in the Fifth Judicial Circuit and Vice Chancellor.4 According to Judge Hunt, “he was the model of a circuit judge. While no proper argument was shortened, no time was lost in tedious harangues.”5 His time as a Circuit Judge was short-lived, however. Four years into his term, illness forced him to resign from the Circuit Court, and he again returned to private practice. He formed the law firm of Denio and Hunt with Ward Hunt, later himself a Judge of the Court of Appeals and a Justice of Supreme Court of the United States. According to an account in the Utica Morning Herald, for some time the firm of Denio and Hunt “served in the fore-front” of the legal profession in the Mohawk Valley.6 Judge Denio served as Bank Commissioner from 1838 to 1840, and then became a clerk of the State Supreme Court in Utica, continuing his private practice.

Denio’s Reports

Between 1845 and 1848, Judge Denio served as Supreme Court Reporter, publishing five volumes of Denio’s Reports. That was a time of major transition in New York court structure and the merger of the courts of law and equity. He reported on the decisions of the old Supreme Court of Judicature, also referred to as simply the Supreme Court, as well as those of the highest court in New York, The Court for the Trial of Impeachments and Correction of Errors.7 The latter court heard appeals from the Chancellor as well as from the Supreme Court, which, although possessing original jurisdiction, served mainly as an appellate tribunal during this period of New York history. Volume 3 of Denio’s Reports also contains reports of some of the first cases argued in the New York Court of Appeals during its November 1847 and January 1848 terms.

Judge Denio appears to have had mixed feelings about the law reforms effectuated by the New York Constitution of 1846. In the final volume of his reports, he prepared a dedication to the “Surviving Justices of the Late Supreme Court of Judicature.” He noted that the original Supreme Court, or at least it was then existing, had been abolished, and remarked:

that court, which, during the whole period of our political existence, has been the highest legal tribunal of original jurisdiction has been abolished by the fundamental law. A new system, required, perhaps, by the increase in population has been substituted for that which has worked so well. . . . [W]hen it has been seen that many of the most able among the members of the legal profession have been, in the first instance, chosen to seats in the new court, . . . no serious apprehension need be entertained that our rights will suffer for want of adequate legal representation.8

However, Judge Denio was apparently not so enamored of the merger of law and equity, which brought in a new system of legal procedure:

Under the specious name of reform, and in professed obedience to a constitutional provision looking only to the modes of practice, all the decisions under which legal rights and remedies had been arranged, and the whole nomenclature of legal science, as learned and practiced in this court has been abolished. The ancient simplicity of the common law has been made to give place to a system in which every case is made a special one.9

While in private practice, Judge Denio collaborated with William Tracy and in 1852 edited a two-volume edition of the Revised Statutes of New York. He also argued 14 cases in the newly-created Court of Appeals-five for the appellant and nine for the respondent, amassing a record of eight wins and six losses. His biggest win by far came in Newell v. People ex rel. Phelps (7 NY 9 [1852]), where the Court of Appeals struck down as unconstitutional an 1851 statute that authorized the use of canal proceeds for the completion of the Erie Canal enlargement.

His Years on the Court

In June 1853, then Governor Horatio Seymour, also a Utica native, appointed Judge Denio to a vacancy on the Court of Appeals created by the resignation of the Court’s first Chief Judge, Freeborn G. Jewett. Judge Denio was elected for the remainder of Judge Jewett’s term in November 1853 and reelected for a full eight-year term in November 1857. He served as the Chief Judge in 1856 and 1857 and again from July 1, 1862 through December 31, 1865, when his term of office expired.10

Judge Denio earned a reputation as a fair and balanced Judge. As noted by Judge Ellis Roberts, Judge Denio possessed

a cast of mind eminently judicial, with studious habits that never wearied, with conversance with the principles as well as the letter of the law seldom surpassed, and with integrity never questioned[;] he deserves to rank with the magnates of the bar, of [Oneida] County and the state and as a member of the Court of Appeals his decisions are accepted as standards and models. He was not a man to startle observers by brilliance and eccentricity. His prudence, his common sense, his thorough conscientiousness were his marked characteristics. . . . As he was without dogmatism, he could admit and correct errors. In every sense he was a good judge, and in some respects his associates have pronounced him among the best and foremost that ever sat upon the bench of our highest tribunal.11

Although Judge Denio was a Democrat, he was not a dogmatic one, as illustrated by vote for President Abraham Lincoln during 1860 and his support of the Union’s efforts during the Civil War. Upon Judge Denio’s death, Judge William J. Bacon remarked, “I can never forget the ringing words he addressed to the first public meeting held in this city [Utica] after the fall of Fort Sumter. He sounded the clarion note which called us all to the platform of duty.”12 Judge Denio’s lack of partisanship is also evidenced by two of his most significant opinions: Lemmon v. The People (20 NY 562 [1860]) and People ex rel. Wood v. Draper (15 NY 532 [1857]).

Lemmon v. The People (20 NY 562) involved a case very similar in its facts to Dred Scott v. Sanford (60 US 393 [1856]), but the Court of Appeals did not follow the much-criticized result in Dred Scott. Judge Denio was the only Democrat to vote with the majority in this case.13

Juliet Lemmon, a citizen of Virginia, was in transit from that state to the State of Texas, bringing her household and property, including eight slaves. They traveled to New York, there to board a steamer for Texas. On November 6, 1852, Lemmon and her slaves spent the night in a house in New York City. While there, Louis Napoleon, “a vigilant colored man of New York,”14 obtained a writ of habeas corpus and served it upon Mrs. Lemmon. The writ alleged that all of Mrs. Lemmon’s slaves were free by virtue of Chapter 137 of the Laws of 1817 as amended in 1841. The original 1817 statute outlawed slavery in New York and provided, with certain exceptions, that any slave brought into the state would be free. The 1841 amendment repealed all the exceptions, including a provision that persons in transit through the state could keep their slaves, provided that they did not remain in New York more than nine months. Thus, because the statute’s plain language required the manumission of Lemmon’s slaves, the only question on appeal from the sustained grant of the writ of habeas corpus was the statute’s validity under the federal Constitution.

Lemmon v. The People took almost six and a half years to reach the Court of Appeals, during a time of increasing unrest in this country over the question of slavery. Virginia actually took over the appeal for Mrs. Lemmon. The case was argued by two titans of the New York Bar, Charles O’Conor for the appellant Lemmon and William M. Evarts for the respondent Negroes seeking freedom.15 Joseph Blunt, the State’s Attorney General, appeared for the People to defend the constitutionality of the statute.

In a 5-3 decision, the Court affirmed the grant of the writ of habeas corpus and held the former slaves were properly freed. Judge Denio authored the Court’s majority opinion. He placed the Court’s decision on the power reserved to the states by the United States Constitution. This included, the Court observed, the power of the states to determine the legal status of persons within their borders. It flatly disagreed with a central premise of Dred Scott-although the majority did not cite that decision-by holding that New York law and not Virginia law governed on the question of whether the Negroes were free citizens or mere property. Judge Denio noted that Article IV, ‘ 2 of the federal Constitution, dealing with fugitive slaves, did not apply because the slaves were not fugitives but had been voluntarily brought into the state by Mrs. Lemmon. The Court rejected the argument that the New York law which gave the slaves their freedom violated the federal Constitution’s Privileges and Immunities Clause. According to Judge Denio,

[w]here the laws of the several states differ, a citizen of one State asserting rights in another must claim them according to the laws of the last mentioned state, not according to the laws which obtain in his own.16

The Court also rejected the argument that the New York statute violated the Commerce Clause, reasoning that even if that clause might have some bearing on slaves involuntarily brought into the state by “consequence of a marine accident or by stress of weather,” the clause did not apply to this case because Mrs. Lemmon voluntarily brought her slaves into New York.17 Judge Denio concluded:

Upon the whole case, I have come to the conclusion that there is nothing in the National Constitution or the laws of Congress to preclude State judicial authorities from declaring these slaves thus introduced into the territory of this State, free and setting them at liberty.18

Judge Denio’s opinion in Lemmon is a competent, dispassionate and logically constructed writing. In one sense, it is representative of its time because of the highly formalistic style, but in another more fundamental sense it is thoroughly modern because it eschewed the Attorney General’s proffer to have the case decided on Natural Law grounds. The opinion is also a model of judicial self-restraint, deciding the questions squarely before the Court and nothing more. One can only wonder whether a terrible and bloody Civil War could have been avoided if Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney took a similar approach in Dred Scott.

A second major opinion for Judge Denio-one for which he took considerable criticism from his Democratic Party, according to the Utica Morning Herald and Judge Amasa J. Parker-also shows his independent and nonpartisan approach to judicial decisionmaking. In People ex rel. Wood v. Draper (15 NY 532 [1857]) the Court upheld the constitutionality of the state law which created a Metropolitan Police District, unifying in some respects the police forces in the counties of New York, Kings, Richmond and Westchester. The law was challenged on the ground that the Legislature and Governor exceeded their power under the State Constitution of 1846, which reserved to the electors or local authorities the right to elect or appoint county, city, town and village officers. The Court held that the State Legislature may constitutionally establish new civil divisions of the state, embracing the whole or parts of different counties, cities, villages or towns, provided the divisions recognized by the Constitution are not abolished nor their capacity rendered “less suitable for the purpose for which they are recognized and employed by the constitution.”19 The Court concluded that the law at issue did not abolish the counties and localities mentioned in the Constitution.

Judge Denio also left his mark on other aspects of constitutional law. In People ex rel. Hackley v. Kelly (24 NY 74 [1861]), a case interpreting the State Constitution’s self-incrimination clause, Judge Denio observed:

constitutional provisions are not leveled at the evils most current at the times in which they are adopted, but, while embracing these, they look to the history of the abuses of political society in times past, and in other countries, and endeavor to form a system which shall protect the members of the State against those acts of oppression and misgovernment which unrestrained political or judicial power are, always and everywhere most apt to fall into.20

In Still v. Village of Corning (15 NY 297 [1857]), Judge Denio wrote for the Court that the Legislature had the power to create new inferior judicial tribunals.

After the Court

Judge Denio was a strong proponent of reforming the structure of the Court of Appeals as it existed under the 1846 Constitution. Under that Constitution, four of the eight Court of Appeals Judges were elected by statewide vote. The other four judges were appointed from “the class of the Justices of the Supreme Court having the shortest time to serve.”21 The constant shifting of the judicial personnel made the Court unwieldy and it was difficult to preserve a uniform and consistent course of decisions. In 1857, then Chief Judge Denio wrote to the Assembly Judiciary Committee asking for a change in the selection process for Judges on the Court, noting the importance of collegiality on a multi-member appellate court.22 This reform was ultimately accomplished by the Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868.

Upon his departure from the Court in December 1865, Judge Denio continued to serve as a trustee for Hamilton College in Clinton, New York. He also received an LL. D. degree from Madison College, later Colgate University. He also continued to devote “a large portion of his valuable time, without any remuneration whatsoever, to the protection of the earnings of the poor, deposited in the Savings Bank of Utica.”23 A great believer in lifelong learning, at the age of 60 Judge Denio “learned the French language, to enable him to peruse such French works as he desired to read, and he read them with facility.”24

Judge Denio suffered a paralytic stroke on October 17, 1868. He partially recovered from the effects of the stroke but he was never again fully himself. The Judge died at his residence in Utica on November 5, 1871, at the age of 72, and is buried at Forest Hill Cemetery in Utica. Upon his death the Utica Morning Herald observed that his life proved “that eminence involves no sacrifice of worth, [and] that purity of personal character is consonant with personal, professional and political success.”25

On the day following his death, the members of the Oneida County Bar met at the courthouse in Utica to pay tribute to a man they loved and respected. There, Judge Denio was heralded by the titans of the Bench and Bar including Judges A.S. Johnson, Francis Kernan, Ward Hunt, William J. Bacon, C.H. Doolittle, Robert Mason and attorney John F. Seymour. Judge Hunt observed:

His career affords an example to all young men. With no aid of friends or family, with no advantage of money, without the benefit of a liberal education, his career was an entire success. He was laborious in duties, and attentive, spending his days not only, but his evenings in his studies.

He held many offices of public trust, and many positions of private confidence. He was always equal to the occasion.26

Two weeks later, on November 21, 1871, the Court of Appeals convened in the State Capitol in Albany to pay tribute to Judge Denio.27 Judge Amasa J. Parker, a longtime Supreme Court Justice who had sat on the Court of Appeals with him for one year pursuant to the provisions of the 1846 Constitution, gave the principal tribute. Judge Parker observed:

His mind was peculiarly adapted to the discharge of the judicial office. It was clear, comprehensive and discriminating, and singularly free from prejudice or bias. He had trained it to close attention, and to the mastery of details. In seeking out and selecting for consideration the true questions involved, he looked at the whole case with conscientious and characteristic fidelity. Though tenacious of his opinions, when deliberately informed, he never failed to treat, with respect, the opinions of those who differed from him. He felt deeply the great responsibility of making a decision from which there could be no appeal.

Judge Parker went on to praise Judge Denio for his personal qualities, which he found “worthy of imitation.” All who knew Judge Denio loved him “for the child-like simplicity of his nature, the unselfish spirit which actuated him, the courtesy of his manner, and the truthfulness and sincerity which governed every action of his life.” Judge Parker observed:

I speak, I am sure, of the opinion of the bar, when I say that no judge ever sat on the bench in this State or elsewhere in whose learning, ability, and purity the public or the profession felt more confidence. History, which rarely fails to do justice to those who have passed away, will inscribe his name on the same page with Kent and Spencer and Bronson. Like them, he will be justly spoken of by those that follow him, as a great lawyer and a great judge.

Chief Judge Church added:

For eminent ability, profound learning and incorruptible integrity, Judge Denio is justly entitled to a position in the very front rank of distinguished jurists which this State and country have produced.

Progeny

Research has not revealed any direct descendants of Judge Denio still living. Only his daughter Elizabeth H. Denio married. She married Dr. Louis Tourtellot of Utica, who was the first assistant physician at the Lunatic Asylum in the area. They had three children: Louis D. Tourtellot (born 1863), Francis Tourtellot (born 1865) and Annie P. Tourtellot (born 1869). The direct genealogy trail ends here, but for more on the Denio family-descendants of Hiram Denio’s great-grandfather and grandfather, both named Aaron Denio-please check the History of the Denio Family web page at http://denio.tripod.com/aaron.htm.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Assembly Document 45, Jan. 28, 1857.

Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, Columbia University Press (1985).

Browne, Irving, The New York Court of Appeals, 2 Green Bag 277 (1890).

But How are Their Decisions to Be Known, Celebrating 200 Years of New York State Official Law Reporting, New York State Law Reporting Bureau, Albany (2004) (booklet on file with author).

Chester, Courts and Lawyers of New York: A History, American Historical Society (1925) (4 volumes).

Chester, The Legal and Judicial History of New York, National Americana Society (1911) (2 volumes).

Cookenham, History of Oneida County from 1700 to the Present, S.J. Clarke Publishing Co. (1912).

Dedication to the Surviving Justices of the late Supreme Court of Judicature, 5 Denio iii.

Francis Brigham Denio and Herbert Williams Denio, A Genealogy of Aaron Denio of Deerfield Massachusetts, 1704-1925, Capital City Press (1926).

Gigante, A House Divided, Columbiad Magazine, Fall 1999, Reprinted on Web at http://afroamhistory.about.com/libray/prm/blhousedivided4.htm (last accessed 3/29/2005) (available on file with the author).

History of the Bench and Bar of New York (various editors) (1897).

In Memoriam 60 Barb (Barbour’s Reports) 659 (1872).

Lincoln, The Constitutional History of New York (1906).

Proceedings on Announcement of the Death of Hon. Hiram Denio, 46 NY 695 (1872).

The Police Imbroglio in the Court of Appeals, The New York Times, January 17, 1857 in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

There Shall be a Court of Appeals, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State Of New York (1997) (booklet on file with the author).

Utica Memorial Herald November 6, 1871, Reprinted in Durant, History of Oneida County Everts & Fariss, Philadelphia (1878).

Wager, ed. Our County & Its People, Boston History Co. (1896).

Published Writings Include:

To this author’s knowledge, Judge Denio did not publish any books of his own. Of course, all of Judge Denio’s opinions for the Court of Appeals were published as were some of his Circuit Court opinions. Judge Denio was the editor of 5 volumes of Denio’s Reports. He published his Tribute to the Surviving Justices of the late Supreme Court of Judicature in Volume 3 of Denio’s Reports. In addition, he edited along with William Tracy a copy of the Revised Statutes of New York in 1852. All of the briefs that Judge Denio wrote and filed with the Court of Appeals are public documents. Many of the private letters written to Judge Denio and some written by Judge Denio are on file in the offices Oneida County Historical Society in Utica, New York.

Endnotes

- Chester, The Legal and Judicial History of New York, National Americana Society (1911), at 224.

- Obituary Notice, Utica Morning Herald, November 6, 1871. Henry Storrs later went on to serve as a member of Congress and a County Court Judge.

- In Memoriam, 60 Barb 659, 662.

- The Circuit Court and the Court of Chancery were abolished by the Constitution of 1846.

- 60 Barb at 662.

- Obituary Notice, Utica Morning Herald, November 6, 1871.

- The Court for Impeachments and the Correction of Errors (or Correction of Errors for short) consisted of the President of the Senate, the Chancellor, the three Justices of the Supreme Court and the 32 State Senators. The Court was abolished by the Constitution of 1846 and in its place the Court of Appeals was created. During this same constitutional reform, the courts of law and equity were merged.

- 5 Denio iii-iv.

- id. at iv.

- Judge Denio was the only Judge to serve two different terms as Chief Judge. He accomplished this feat because under the rule in effect then, the elected Judge, who had the shortest time to serve on the Court, was automatically the Chief Judge. Judge Denio’s 13 years on the Court was an extremely long tenure for this era (see Bergan, The History of The New York Court of Appeals, Columbia Univ. Press [1985], at 42).

- Obituary Notice, Utica Memorial Herald, November 6, 1871.

- 60 Barb at 664.

- Giagante, Slavery and a House Divided Part 4: Lemmon v. People, Columbiad Magazine, Fall 1999.

- Springfield Daily Republican, October 12, 1857, at 2.

- Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, Columbia Univ. Press (1985), at 69. Later, Judge Denio along with four of his other colleagues on the Court wrote a letter to President Lincoln seeking to secure a seat on the Supreme Court of the United States for Mr. Evarts.

- 20 NY at 609.

- 20 NY at 612.

- 20 NY at 615.

- 15 NY at 542.

- 24 NY at 81-82.

- Const of 1846, Art VI, ‘ 2.

- 1857 Assembly Document 45, January 28, 1857.

- 60 Barb at 669.

- 60 Barb at 667.

- Obituary Notice, Utica Morning Herald, November 6, 1871.

- 60 Barb at 662.

- The tribute, from which the following quotations are taken, begins at 46 NY 696.