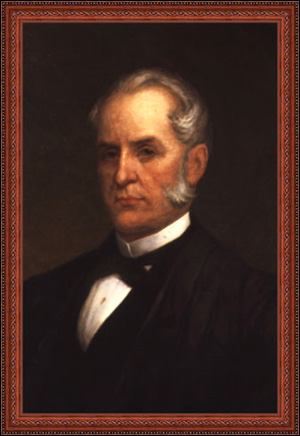

Along with Judges Benjamin Cardozo and Rufus Peckham Jr., Judge Ward Hunt has the distinction of having been a judge of the Court of Appeals who later sat on the United States Supreme Court. He is also known for having been the trial judge in the federal prosecution of Susan B. Anthony for voting in Rochester, New York in 1872.

Ward Hunt, born on June 14, 1810, in Utica, New York, to Montgomery and Elizabeth (Stringham) Hunt, was the third of eight children.1 Mrs. Hunt was the daughter of Capt. Joseph Stringham of New York. The family was originally from Westchester County. Judge Hunt was a descendant of Thomas Hunt who resided in Stamford, Connecticut circa 1650. For many years, Judge Hunt’s father, Montgomery Hunt,2 was the cashier at the First National Bank of Utica.

Education

For his early education, Judge Hunt attended Oxford and Geneva Academies in Utica. In both schools, future New York State Governor Horatio Seymour was a classmate. After brief study at Hamilton College, he graduated with honors from Union College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1828 at the age of 18.3 He went on to study law in Utica in the practice of Hiram (later Judge) Denio (1799-1868), and then from 1830-1831 at the Tapping Reeve House in Litchfield, Connecticut. Judge Hunt was admitted to the bar in New York in 1831.

A Life of Law and Politics

Due to poor health, Hunt was not able to assume practice immediately but was forced to spend the winter in New Orleans in order to recuperate. Upon his return, he established a law partnership with Hiram Denio, his former mentor. In private practice from 1832 to 1865, Hunt established a large and lucrative practice in part due to his legal skills and in part due to clients from his father.4 During this time, Hunt was also associated with Benjamin F. Cooper, William L. Walradt, Montgomery H. Throop (a codifier of New York State laws), and Daniel Waterman, Jr. However, Hunt had a calling to the bench “for which he was eminently fitted by what is generally called a “judicial mind.”5

In 1838, he was elected to the New York State Legislature, where he served one term. In 1844, while in practice, he was elected Mayor of Utica. He later ran for a seat on the Court of Appeals and received the Democratic nomination over Philo Gridley6 but was defeated at the polls. According to one commentator, he lost due to his successful defense of a police officer who fatally shot an Irishman, costing him the Irish vote and the election.7

Undaunted, Hunt ran a second time in 1853 and again lost, this time to William J. Bacon. This time his defeat was due to his break with the Jacksonian Democrats over his opposition to the extension of slavery into the northern states and his support of the candidacy of Martin Van Buren and Adams on the Free-Soil ticket in 1848. In 1855, Hunt helped form the Republican party, which regarded him as a possible candidate for the US Senate at the party’s caucus in Albany.

In 1865, he was elected to the Court of Appeals by more than 32,000 votes to replace his mentor Judge Denio who had become a Court of Appeals Judge in 1853. In 1868, with the death of Judge William B. Wright and the resignation of Judge John K. Porter, Ward Hunt became Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, and held that position only until the end of 1869. Due to a restructuring of the Court and a constitutional amendment, Judge Ward became a Commissioner of Appeals from 1870-1872.8 In 1872, United States Supreme Court Justice Samuel Nelson resigned. At the urging of Senator Roscoe Conkling (a friend of Judge Hunt), President Ulysses S. Grant nominated Judge Hunt to serve on the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court Justice

The Senate confirmed Judge Hunt’s nomination on December 11, 1872, and he took the bench on January 9, 1873. A column in the New York Times lauded the choice:

No appointment which President Grant has made has been based upon stronger recommendations than that of Judge Ward Hunt to the Supreme Court of the United States. For nearly thirty years, Judge Hunt has been well known as a leading lawyer of New York, and has occupied the highest judicial position which the State can bestow with the greatest credit.9

As part of his duties as a Supreme Court Justice, Hunt was required to hear trial-level cases as a federal circuit court judge. His best known decision was United States v. Anthony (24 F. Cas. 829, 830 [N.D. Cir. Ct., 1873]):

On November 1, 1872, [Susan B.] Anthony and her three sisters entered a voter registration office set up in a barbershop. The four Anthony women were part of a group of fifty women Anthony had organized to register in her home town of Rochester. As they entered the barbershop, the women saw stationed in the office three young men serving as registrars. Anthony walked directly to the election inspectors and, as one of the inspectors would later testify, ‘demanded that we register them as voters.’10

At the eighth ward of the City of Rochester, in November 1872, Anthony demanded the right to vote, citing the Fourteenth Amendment and her citizenship rights. When the voting inspectors would not yield, she is quoted as saying “If you refuse us our rights as citizens, I will bring charges against you in Criminal Court and I will sue each of you personally for large, exemplary damages!” She went on to say, “I know I can win. I have Judge Selden as a lawyer. There is any amount of money to back me, and if I have to, I will push to the last ditch in both courts.”11 The men finally gave in and allowed fourteen women to register to vote. On November 5, 1872, Anthony along with seven or eight other women voted. In a letter to her friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Anthony reported that she voted a straight Republican ticket.12

On November 18, Anthony was arrested and charged with illegal voting in violation of the 1870 Enforcement Act, a federal offense. After she refused to enter a plea, a hearing was held to establish whether or not she had cast a “willful and knowing” illegal vote. The hearing was adjourned to December 1872, and at the end of the hearing, Commissioner William Storrs found that Anthony had violated the law. She refused bail and was jailed. Reportedly, Anthony thought that by remaining in jail the case would get to the Supreme Court on a habeas corpus petition. Ultimately, however, Judge Selden,13 her attorney paid her bail.

A grand jury indicted her for “knowingly, wrongfully, and unlawfully” voting for a member of Congress “without having a lawful right to vote . . . the said Susan B. Anthony being then and there a person of the female sex.” The trial was initially set for May 1871 but the prosecutor believed that Anthony had influenced the potential jury pool with her lectures throughout Monroe County, and asked Justice Hunt to change the venue to Canandaigua, in Ontario County. Judge Hunt agreed and set a new date for June 17, 1873. Anthony lectured for 21 days in Ontario County before her trial.

In the United States v. Anthony decision of June 18, Justice Hunt, sitting as a Circuit Justice determined that the rights identified under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments were guaranteed to citizens of the United States not citizens of the states.

He thus ruled that each state had the right to set-out its voting qualifications:

If the state of New York should provide that no person should vote until he had reached the age of thirty years, or after he had reached the age of fifty, or that no person having gray hair, or who had not the use of all his limbs, should be entitled to vote, I do not see how it could be held to be a violation of any right derived or held under the constitution of the United States. We might say that such regulations were unjust, tyrannical, unfit for the regulation of an intelligent state; but, if rights of a citizen are thereby violated, they are of that fundamental class, derived from his position as a citizen of the state, and not those limited rights belonging to him as a citizen of the United States (US v. Anthony, 24 F. Cas. 829, 830 [1873]).

After deciding that the Fifteenth Amendment said nothing about women having the right to vote, Justice Hunt held that “The regulation of the suffrage is thereby conceded to the states as a state’s right” (id. at 831). Refusing to submit the case to the jury, he directed the court clerk to enter a verdict of guilty against Anthony, then turned to the panel and stated “Gentlemen of the jury, you are discharged.”14

The next day, Judge Selden, Anthony’s attorney, made a motion for a new trial, which Justice Hunt denied. He then had a heated exchange with Susan B. Anthony:

COURT: Has the prisoner anything to say why sentence shall not be pronounced?

ANTHONY: Yes, your honor, I have many things to say; for in your ordered verdict of guilty, you have trampled under foot every vital principle of our government. My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all alike ignored. Robbed of the fundamental privilege of citizenship, I am degraded from the status of a citizen to that of a subject; and not only myself individually, but all of my sex, are, by your honor’s verdict, doomed to political subjection under this, so-called, form of government

COURT: The Court cannot listen to a rehearsal of arguments the prisoner’s counsel has already consumed three hours in presenting.

ANTHONY: May it please your honor, I am not arguing the question, but simply stating that reasons why sentence cannot, in justice, be pronounced against me. Your denial of my citizen’s right to vote, is the denial of my right of consent as one of the governed, the denial of my right to a trial by a jury of my peers as an offender against law, therefore, the denial of my sacred rights to life, liberty, property and-

COURT: The Court cannot allow the prisoner to go on.

ANTHONY: But your honor will not deny me this one and only poor privilege of protest against this high-handed outrage upon my citizen’s rights. May it please the Court to remember that since the day of my arrest last November, this is the first time that either myself or any person of my disfranchised class has been allowed a word of defense before judge or jury.

COURT: The prisoner must sit down-the Court cannot allow it.

ANTHONY: All of my prosecutors, from the eighth ward corner grocery politician, who entered the complaint, to the United States Marshal, Commissioner, District Attorney, District Judge, your honor on the bench, not one is my peer, but each and all are my political sovereigns; and had your honor submitted my case to the jury, as was clearly your duty, even then I should have had just cause of protest, for not one of those men was my peer; but, native or foreign born, white or black, rich or poor, educated or ignorant, awake or asleep, sober or drunk, each and every man of them was my political superior; hence, in no sense, my peer. Even, under such circumstances, a commoner of England, tried before a jury of Lords, would have far less cause to complain than should I, a woman, tried before a jury of men. Even my counsel, the Hon. Henry R. Selden, who has argued my cause so ably, so earnestly, so unanswerably before your honor, is my political sovereign. Precisely as no disfranchised person is entitled to sit upon a jury, and no woman is entitled to the franchise, so, none but a regularly admitted lawyer is allowed to practice in the courts, and no woman can gain admission to the bar-hence, jury, judge, counsel, must all be of the superior class.

COURT: The Court must insist the prisoner has been tried according to the established forms of law.15

On June 18, 1873, Justice Hunt sentenced Anthony to pay a fine of one hundred dollars and the costs of prosecution, a penalty she refused to pay and in fact never paid.16

Justice Hunt took a somewhat different view when it came to the voting rights of males of African descent in United States v. Reese (92 US 214, 216-222 [1875]). The case involved the legal responsibility of Kentucky voting inspectors to accept the votes of males of African descent. The majority held that while the Fifteenth Amendment provided for the punishment of electors for racial discrimination against citizens of the United States and residents of the state, it did not provide for the punishment of inspectors of elections who were charged only with collecting and counting votes. Also, the majority held that the indictment was insufficient and thus, affirmed the opinion of the lower courts. The ruling weakened the Enforcement Act of 1870 and impeded implementation of the Fifteenth Amendment. Justice Hunt dissented:

I hold, therefore, that the third and fourth sections of the statute we are considering do provide for the punishment of inspectors of elections who refuse the votes of qualified electors on account of their race or color. The indictment is sufficient, and the statute sufficiently describes the offence (see 92 US 214, 245, supra).

. . .

The persons affected were citizens of the United States; the subject was the right of these persons to vote, not at specified elections or for specified officers, not for Federal officers or for State officers, but the right to vote in its broadest terms (see 92 US 214, 248, supra).

Justice Hunt found that the provisions of the Enforcement Act requiring inspectors to accept the vote of males of African descent were in fact constitutional and violations were punishable by law.

In United States v. Cruikshank, 92 US 542, 556 [1875], however, a case from Louisiana involving a band of individuals who conspired to prevent a male of African descent from voting, Justice Hunt sided with the majority in holding that based on Reese, there was no violation of the Enforcement Act of 1870. The court reasoned that the “right to vote in the States comes from the States; but the right of exemption from the prohibited discrimination comes from the United States. The first has not been granted or secured by the Constitution of the United States; but the latter has been.”

The Court then found that it is not a constitutional violation for two or more people to combine to prevent someone from voting. The Court upheld state regulations, bondholder claims, and police powers as against claims of racial equality under the Fourteenth Amendment.

After writing 149 Supreme Court opinions, eight of which addressed constitutional issues, and four dissenting opinions (dissenting 18 times without opinion) Justice Hunt’s health once again was in decline. He suffered from gout, and heard his last case in the December 1878 term.

In January 1879, he suffered a paralytic stroke to his right side and never returned to full health. He served on the Supreme Court until 1882 when Congress passed an act allowing him to retire with less than ten years of service on the court. On February 17, 1882, one day after the bill was enacted, Judge Hunt resigned with full pension. In a letter dated March 4, 1882 and published at 105 US ix-x [1882], his associate justices wrote:

Dear Judge Hunt, -Your resignation as one of our number having taken place just at the beginning of the February recess, we have had no opportunity until now of expressing to you our regret that your long-continued illness made such a step necessary. We have none of us forgotten how faithfully you labored, while health permitted, to perform your full share of the work that was constantly pressing upon us, and we cannot but feel that if you had been more careful of your strength, and less determined to do all of what you conceived to be your duty, the necessity for this separation would not have existed. Your absence from the bench has not taken from us the recollection of your conscientious service while there, nor of your uniform kindness and courtesy everywhere and on all occasion.

With sincere regard we remain your friends and former associates,

M.R. Waite,

Sam F. Miller,

Stephen J. Field,

Joseph P. Bradley,

John M. Harlan

Judge Hunt died in Washington, D.C. on March 24, 1886, and is interred in Utica, New York.

Progeny

On November 8, 1837, Judge Hunt married Mary Ann Savage, a daughter of New York State Chief Justice Savage (1779-1863), with whom he had three children: Eliza, born October 5, 1838, married Arthur B. Johnson of Utica, New York; John Savage Hunt, born December 9, 1839, held a commission in the Fourth Regiment of the US Artillery; Ward, Jr., born September 5, 1843, became a lawyer. The first Mrs. Hunt died in 1846. On June 18, 1853, he married Maria Taylor, the daughter of James Taylor, Esq., who for many years was the Cashier of the Commercial Bank of Albany. His second wife survived him. There were no children from the second union.

His grandson, Ward Hunt,17 died on August 31, 1901, in Castile, New York. He practiced with the law firm of Waterman & Hunt in Utica before moving to Colorado Springs, Colorado, for health reasons. He later moved back to the Utica, New York, area after his father died and his own health began to decline. Ward Hunt had one son, John Savage Hunt, who practiced law in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

John Savage Hunt died in Utica, NY at the age of 45.17 Admitted to the bar on August 12, 1893, he had been a leading mining lawyer in Colorado Springs. According to the El Paso County, Colorado Bar Association, Mr. Hunt was a founding member of the Colorado Bar Association. As yet, no living progeny have been found.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Albany Law Journal, “Judge Hunt and the Commission of Appeals,” January 11, 1873.

Bergan, History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, New York, Columbia University Press, (1985).

Collections of Schaffer Library, Union College, Schenectady, New York 12308, “Ward Hunt,” 1828.

Cushman, [Ed.], The Supreme Court Justices, Illustrated Biographies, 1789-1993, Congressional Quarterly, Inc. (1993).

Fairman, Mr. Justice Miller and the Supreme Court, 1862-1890, Harvard University Press (1939), 373-400.

Hooker, “Judge Hunt and the Right of Trial by Jury” in Isabella Beecher Hooker, The Constitutional Rights of the Women of the United States. An Address before the International Council of Women, Fowler & Miller, (1888).

In Memoriam, “Ward Hunt, LLD,” 118 US 701-702 (1886).

Kutler, “Ward Hunt: The Justices of the United States Supreme Court 1789-1968: Their Lives and Major Opinions, Vol. II.” Friedman, L. and Israel, F.L., [Eds.] Chelsea House Publishers in assoc. with R.R. Bowker Co., (1969), 1221-1239.

Memoranda, 105 US, ix-x [1882].

National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Vol. 2, New York: James T. White & Co., 1891, 475-476.

New York Daily Times (1851-1857), Sep. 24, 1853.

New York Times, December 9, 1872, pg. 4, column 2.

New York Times, January 10, 1873, pg. 5, column 5.

The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States 417 (Kermit L. Hall, James W. Ely, Jr., Joel B. Grossman & William M. Wiecek, eds., Oxford U.P. 1992).

“There Shall be a Court of Appeals”, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York [1997].

Utica Morning Herald and Daily Gazette, obituary, March 25, 1886.

Published Writings

While we know of no published articles or books by Judge Hunt, letters of his are on file at the New York Historical Society and the University of Chicago addressed to William Evarts, and Henry S. Randall, prominent New York attorneys at that time.

Endnotes

- Ward Hunt’s siblings were Frances (b.1806), James Stringham (b.1808-d.1862), Lydia (b.1813), Montgomery, jr. (b.1816-d.1854), John Stringham (b.1818), Cornelia (b.1820), and Elizabeth (b.1823-d.1828), http://trees.ancestry.com/owt/person (visited July 20, 2005).

- “His father was Monty Hunt, who had come to Utica in the previous year to represent the Manhattan bank of New York, and who in 1812 was active in the organization of the bank of Utica, now the First National”, Utica Morning Herald and Daily Gazette, Tuesday, March 25, 1886.

- Judge Hunt received honorary doctor of law (LL.D.) degrees from Union College and Rutgers in 1870.

- The 1850 census for the City of Utica, County of Oneida, State of New York, Ward Hunt was listed as a male, age 36, a lawyer, owning real estate valued at $10,000. His three children were listed as Eliza (11), John (10), and Ward, jr. (7). His brother John Hunt (25) is listed as a clerk. The census had to have been completed before 1850 because the ages are lower than what they would have attained in 1850.

- Obituary, New York Times, January 10, 1873.

- New York Daily Times (1851-1857), Sep. 24, 1853. Gridley (1796-1864) served ex-officio on the Court of Appeals in 1852.

- Cushman,[Ed.], The Supreme Court Justices, Illustrated Biographies, 1789-1993, Congressional Quarterly, Inc. (1993).

- Bergan, History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, New York, Columbia University Press,[1985], p. 92, 116-117.

- New York Times, December 9, 1872, p. 4, col. 2.

- This is an account by law Professor Douglas Linder published in the Jurist Legal News & Research, “The Trial of Susan B. Anthony For Illegal Voting”, http://64.233.161.104/search?q=cache:0g8Wmrn06m4J:jurist.law.pitt.edu/famoustrials/ant (visited February 28, 2005). See also, An account of the Proceedings of the Trial of Susan B. Anthony on the Charge of Illegal Voting at the Presidential election of Nov, 1872 and the Trial of Beverley W. Jones, Edwin T. Marsh and William B. Hall, The Inspectors of Election by Whom her Vote was Recorded. Rochester, N.Y.: Daily Democrat and Chronicle Book Print, 3 West Main St, 1874.

- Id.

- Id.

- Judge Henry R. Selden (1805-1885) served on the New York State Court of Appeals from 1862-1864. Anthony was also represented by John Van Voorhis (1891-1905), father of John Van Voorhis who served on the Court of Appeals from 1953-1967.

- “Arrest and Trial”-http://secure.palmdigitalmedia.com, (visited February 28, 2005), excerpt from American Women of Achievement by Barbara Weisberg and Matina S. Horner, Chelsea House Publishers (1988).

- Linder, supra, p. 12.

- United States of America v. Anthony, Cir. Ct., N.D.N.Y., June 17-18, 1873, http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/history/dubois, (visited March 1, 2005), Susan B. Anthony: “May it please your honor, I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty. All the stock in trade I possess is a $10,000 debt, incurred by publishing my paper-The Revolution-four years ago, the sole object of which was to educate all women to do precisely as I have done, rebel against your man-made, unjust, unconstitutional forms of law, that tax, fine, imprison, and hang women, while they deny them the right of representation in the Government; and I shall work on with might and main to pay every dollar of that honest debt, but not a penny shall go to this unjust claim. And I shall earnestly and persistently continue to urge all women to the practical recognition of the old revolutionary maxim, that Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.” See also Hammond, Comment, “Trial and Tribulation: The Story of United States v. Anthony,” 48 Buffformatting checked, November 7, 2005alo L Rev 981 (2000).

- Information on the grandson and great-grandson taken from the Utica Herald-Dispatch and Daily Gazette, Thursday, September 5, 1901.

- Information taken from the Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, June 27, 1911.