Though Rufus W. Peckham, Jr. spent nine years on the New York State Court of Appeals, his most famous writing may be an opinion he penned as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

In the notorious case Lochner v. New York (198 US 45 [1905]) Justice Peckham, a zealous defender of personal property rights, handed labor activists a serious defeat in their efforts to reform labor laws and protect the health and safety of workers. In the 5-4 decision invalidating New York’s law prohibiting bakers from working more than ten hours a day or more than 60 hours in one week, the Supreme Court held that the law was not a valid exercise of the state’s police powers and that regulation of the health and safety of workers unconstitutionally interfered with Lochner’s right under the Constitution’s contract clause to engage freely in his business. Labor leaders and reformers contended that baking-which involved long hours and arduous conditions-was a hazardous profession and that the state was within constitutional parameters in regulating it. The Court, and Justice Peckham, disagreed. Believing the law was not justified on health grounds but was rather a thinly veiled attempt to limit work hours and hinting that the labor reformers might have communist sympathies, Justice Peckham wrote that “[t]he freedom of master and employee to contract with each other . . . cannot be prohibited or interfered with without violating the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of liberty” (198 US at 64).

In a biting dissent, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. accused the majority of imperiously employing their own personal views of laissez-faire economics to strike down reasonable laws passed by elected representatives of the State’s citizens. He wrote that “[s]ome of these laws embody convictions or prejudices which judges are likely to share. Some may not. But a constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory” (198 US at 75).1 Indeed, Justice Peckham has long been remembered for invoking the concept of substantive due process in the context of economic civil liberties. A series of subsequent Supreme Court opinions weakened Justice Peckham’s central holding and what has been called the “Lochner age” was dealt its final blow with West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (300 US 379 [1937]), which, though not explicitly overruling Lochner, finally upheld a state’s minimum wage statute.2

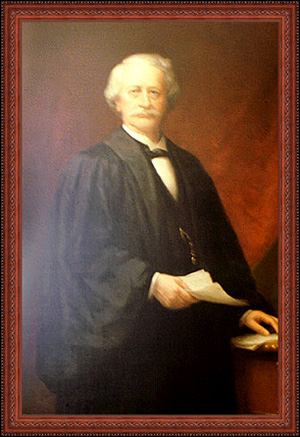

Long before joining the Supreme Court, Justice Peckham had reached the highest echelons of the legal profession. Born in Albany, New York on November 8, 1838 into a distinguished family of attorneys, Justice Peckham was the son of Rufus W. Peckham, Sr. (1809-1873), a lawyer, Congressman and Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals (1865-1867) who perished at sea in 1873. Justice Peckham’s uncle George was also a renowned New York attorney as was the Justice’s brother Wheeler. The Peckham men were said to have born an uncanny resemblance to each other. Rufus W. Peckham, Jr. could easily have been mistaken for his father, with his bushy white hair and mustache, cameo face, and piercing eyes.

Educated at the Albany Boys’ Academy, from which he was graduated in 1856, Justice Peckham also studied privately with tutors in Philadelphia. After completing his formal studies, he embarked for a year of travel and further education in Europe, returning to Albany to read law with his father. Ruminations on his childhood are few and far between, and it appears that the relationships which sustained him throughout his life were developed after Justice Peckham reached adulthood. Upon his death, the State Bar Association’s commemoration committee wrote that “there are few of us who can remember [Justice Peckham] in the days before he became a Judge, in the freedom from restraint and reserve of ordinary professional life.”

Having privately studied the profession, Justice Peckham was admitted to the New York bar in 1859 and practiced in his father’s firm for ten years. While he neither attended university nor had a formal legal education, Justice Peckham was an exceptionally gifted oral advocate and in both civil and criminal law was almost uniformly successful. After Rufus W. Peckham, Sr. was elected state Supreme Court justice and then associate judge of the Court of Appeals, his son continued the law partnership with his father’s former law partner Lyman Tremain, another highly respected advocate of his day. Over the course of ten years Justice Peckham developed into a highly regarded lawyer in his own right, representing primarily corporate clients. Among his more famous clients was the Albany & Susquehanna Railroad, for whom he acted as counsel in its famous fight against the raid of the company by the Erie Railroad, co-owned by American robber barons Jay Gould and James Fisk. As an advocate, Justice Peckham was described by his colleagues as “vigorous” and of “forceful character, frank and outspoken.”3 After a decade in private practice in Albany, however, Justice Peckham, like his father before him, heeded the call of public service.

From his father’s law firm, the younger Rufus W. Peckham followed the paternal footprints to the office of District Attorney for the City and County of Albany, which office he held from 1869 until 1872. During his years as a prosecutor, he also served as a special assistant to the state Attorney General in a series of criminal cases, bringing him further attention and renown for his demonstrated skills and talents.

Justice Peckham immersed himself in Democratic politics as both a supporter of other candidates, in a move that would prove quite professionally rewarding, he befriended future President Grover Cleveland (President from 1885 to 1889, and again from 1893 to 1897) during the future President’s years in upstate New York, and as an active participant in electoral events. He represented his Congressional district at the National Democratic Convention of 1876 and during that election cycle was an ardent supporter of Samuel J. Tilden for the Presidency.

In 1883 Justice Peckham successfully ran for office as judge of the state Supreme Court. He served in that capacity for three years before election to the Court of Appeals, where he remained until President Cleveland nominated him to the United States Supreme Court in 1895. Highly versatile and an agile thinker, Justice Peckham wrote a number of Court of Appeals opinions with such depth that lawyers considered them to be treatises on the topics. Examples are: impeachment of one’s own witness (Becker v. Koch, 104 NY 394 [1887]), the limit of government regulations in the face of real property rights (NY Health Dept. v. Trinity Church Corp., 145 NY 32 [1895]), the right to privacy as related to reproduction of one’s image (Schuyler v. Curtis, 148 NY 754 [1896]) and taxation of charitable institutions (Colored Orphan Asylum v. The Mayor of New York, 104 NY 581 [1887]).

While serving on the Court of Appeals, Justice Peckham invested in a large estate and tract of land near Albany at Knowersville. Apparently wanting to explore the land as well as the law, he determined to use the land for agricultural purposes, hiring a farmer to grow and harvest hay. But Justice Peckham’s enthusiasm may have exceeded his knowledge of farming. After his workers had harvested the bales, Justice Peckham returned to the estate one day noting that the fields had been cut clean, but confused as to what the piles of wet grass were doing on his property. He was quite surprised to learn that the wet grass he believed to be refuse was in fact the very hay he had set out to harvest.4

With deep roots in New York State, the entire Peckham family was invested in both its land and its politics. Justice Peckham’s older brother Wheeler, another esteemed attorney in the Peckham family tradition, was as politically active in Democratic politics as his younger brother. Having supported the upstate faction of the New York State Democrats, Wheeler Peckham had also developed a friendship with President Cleveland, whom he supported in a series of political battles against the downstate faction. On July 7, 1893, fellow New Yorker and United States Supreme Court Justice Samuel Blatchford died, creating a vacancy for President Cleveland to fill. The President first nominated William B. Hornblower,5 one of the greatest courtroom lawyers of his day, but Senator David Hill, Democrat of New York who had been in a patronage squabble with President Cleveland, torpedoed the nomination in an exercise of political power against his adversary.6 The President then nominated Wheeler H. Peckham who was also unwittingly caught in the political tug-of-war between Senator Hill and President Cleveland (who had defeated Senator Hill in the 1892 Democratic presidential primary).7 Senator Hill urged his fellow Senators to reject the President’s nomination of Wheeler, which they did by a vote of 32-41. Senator Edward Douglass White was ultimately confirmed for that contested Supreme Court seat.

Two years later President Cleveland had the opportunity to appoint another Supreme Court justice due to the death of Justice Howell E. Jackson. The President turned to Rufus W. Peckham, Jr. who, perhaps in part due to Senator Hill’s weakened political position, was confirmed in six days.

After his confirmation to the United States Supreme Court, Justice Peckham restricted his already limited social life and stopped giving any sort of public addresses. Such introversion did not, however, prevent him from maintaining a presence in the national and New York Democratic political landscape. He continued to advise President Cleveland on some matters and was even mentioned as a potential nominee for a future New York gubernatorial election. Prior to the Democratic nomination of New York State Court of Appeals Judge Alton Parker for the Presidency in 1891, Justice Peckham’s name was prominently mentioned as a candidate for the office and again it was bandied about as a possibility for the 1900 presidential election.

Justice Peckham developed many close friendships with his colleagues during his nine years on the Court of Appeals and his tenure on the United States Supreme Court. The senior justice of the United States Supreme Court, Melville W. Fuller (Chief Justice from 1888-1910), in eulogizing Justice Peckham said that he was

one of the ablest jurists who ever sat on the American Bench. He was absolutely pure in mind and thought, and free from everything that would prevent him from rendering an honest judgment in any case brought before him. He had strong political convictions; but when on the Bench he knew no litigants’ politics and cared nothing for them. His sole desire was to administer the law as it was and to give each party in every case his just rights.

In addition to his close working relationships with his fellow judges, Justice Peckham maintained friendships with a number of famous tycoons, among them J. Pierpont Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and John D. Rockefeller. In fact, during his years outside public service, Justice Peckham served as counsel or trustee or both for many banking, insurance, and other corporations, and his own investments were considerable. In 1884 he was elected a trustee of the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York, and continued in that capacity for twenty-one years. His associates on the board of trustees of that company included many of the most powerful capitalists in the world, such as George F. Baker, Henry H. Rogers, William Rockefeller, James Speyer, and many others of lesser, but still enormous, power.

Though many people believed these relationships predisposed Justice Peckham to a pro-business position as a jurist, his powerful opinions in a series of antitrust cases should belie any such inference. In a case against the Trans-Missouri Freight Association, for example, Justice Peckham held against a combination between railroads trying to fix rates. In the opinion, he wrote that such conduct violated Federal antitrust statutes, which made invalid all restraints of trade, not merely unreasonable restraints (United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Ass’n, 166 US 290, 328 [1897]). The Supreme Court soon thereafter backed away from the position that all restraints of trade violated Federal law. In yet another opinion by Justice Peckham, the Court recognized that those restraints “merely ancillary or incidental to another legitimate purpose” were not necessarily illegal (Addyston Pipe & Steel Co. v. United States, 175 US 211 [1899]). However, in Addyston Pipe & Steel the Court still held against the business, declaring that an agreement between manufacturers and dealers against competition between them in certain states and territories was a violation of the antitrust laws. Confident of the rightness of his results and thoughtful in his reasoning and analysis, Justice Peckham’s writing style, according to one Supreme Court historian, “more nearly approached that of an essayist than any other Justice.”8

Justice Peckham received honorary degrees from Union College in 1894, from Yale in 1896, and from Columbia in 1901. In 1866 he married Hariette M. Arnold, daughter of D.H. Arnold, a prominent New York merchant and president of the Mercantile Bank of the city. The couple had two sons, both of whom predeceased Justice Peckham, causing their father great grief. In 1909, while still an active Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, Justice Peckham suffered a particularly debilitating asthma attack. Though he had been in ill health for some time, the attack appears to have marked the beginning of a precipitous decline in his health, which culminated in the fatal heart attack he suffered on October 24, 1909, while trying to regain his health at his estate in Altamont, New York. His body was laid to rest in the family plot at Rural Cemetery in Albany.

The name of Rufus Wheeler Peckham, Jr. was sure to live on in New York State history, associated not only with legal and judicial distinction, but also with the maritime industry. In 1943 the Bethlehem Steel Company launched a 10,000 ton ship named in honor of Rufus W. Peckham, Jr. The Peckham, a World War II ship, was launched on February 13, 1943 and was active until 1959, when it wrecked and sank.

Progeny

Rufus W. Peckham, Jr. had two sons who predeceased him. One son, Rufus, also a lawyer who practiced in the New York City office of his uncle Wheeler’s law firm, died childless in 1899. While Rufus died without heirs, the other son, Henry, left at least two sons, Harry and Rufus. The only living descendant presently identified is Rufus W. Peckham, Jr., an attorney in the Washington, D.C. area.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

21 Green Bag 662 (1909).

30 Alb. L. J. 160 (1884-1885).

55 Alb. L. J. 210 (1897).

60 Alb. L. J. 190, 190-191 (1899-1900).

Battershall, Henry Arnold Peckham and Rufus Wheeler Peckham, Jr: A Memoir, J.B. Lyon Co. (1909).

Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932 Columbia University Press (1985).

Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, page 1396.

Browne, The New York Court of Appeals, 2 Green Bag 277, 337-338 (1890).

Collection of newspaper obituaries in the New York State Library.

Hall, 8 Green Bag 1, 1-4 (1896).

Hayes, Wheeler H. Peckham, 18 Green Bag 57 (1906).

History of the Bench and Bar of New York, Vol. 1, p. 442, New York History Co., 1897.

History of the Supreme Court of the United States, Charles H. Kerr & Co., Chicago, 1925, p. 627.

“The Insurance Year Book,” 1905, p. 175.

King, Melville Weston Fuller: Chief Justice of the United States 1888-1910, Macmillan Co., 1950, p. 191.

Lasky, Rufus W. Peckham, His Life and Times: A Study in American Conservatism, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University, 1951.

Legal and Judicial History of New York, Vol. III, National Americana Society, New York, 1911, p. 47-48.

Obituaries, New York Times, October 25, 1909, p. 1 and October 26, 1909, p. 8.

Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, Hall, Kermit L., ed., 1992, pp. 626-627.

Pratt, Rhetorical Styles on the Fuller Court, 24 Am. J. Legal Hist. 189 at 208, 21, 213 (1980).

Proceedings of the Bar and Officers of the Supreme Court of the United States in Memory of Rufus Wheeler Peckham, December 18, 1909.

Proceedings of the Special Meeting of the New York State Bar Association in Commemoration of the Life and Services of the Late Mr. Justice Rufus W. Peckham, December 9, 1909.

Proceedings in The Senate on The Investigation of The Charges Preferred Against John H. McCunn,@ etc., Albany, 1874: pp. 80, 100, 102, 110, 134, 142.

Schwartz, A Book of Legal Lists, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 36.

Spencer, Mr. Justice Peckham and the Sherman Act, 21 Green Bag 614 (1909).

There Shall be a Court of Appeals, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York, (1997) (booklet on file with the author).

Endnotes

- It appears that Justice Holmes did not hold Justice Peckham in great intellectual regard. When asked once what Justice Peckham was like “intellectually,” Justice Holmes answered “I never thought of him in that connection. His major premise was ‘God damn it.'”

- Though Lochner v. New York may be Justice Peckham’s most notorious writing, the most maligned opinion in which he concurred is likely Plessy v. Ferguson (163 US 537 [1896]), approving of laws segregating public facilities on the basis of race and prohibiting African Americans from using those facilities.

- Justice Peckham also defended some of the more notorious figures of the day. In 1872 he was one of the counsels to Tammany judge John H. McCunn, defending Judge McCunn against corruption charges. The defense was ultimately unsuccessful and Judge McCunn was convicted of eight counts, impeached and removed from office.

- 30 Alb. L. J. 160 (1884-1885).

- William B. Hornblower (1851-1914) would later serve on the Court of Appeals in 1914.

- Although President Cleveland won the presidential election in 1892, Senator Hill and his downstate New York political allies remained powerful in state politics. They claimed success in having their candidate elected governor and in taking over both houses of the state legislature. Prior to blackballing Wheeler Peckham’s nomination, Senator Hill doomed another nomination to the same Supreme Court vacancy, claiming “senatorial courtesy” a Senate custom dating back to at least 1789 by which a high-level federal nominee must not be offensive to the nominee’s home state Senator on risk of invoking the tradition, which virtually ensures defeat in the Senate.

- Wheeler H. Peckham gained fame by, among other accomplishments, prosecuting the corrupt New York City Tweed Ring in 1873 as an appointed Special Deputy District Attorney and Special Deputy Attorney-General.

- Walter F. Pratt, “Rhetorical Styles on the Fuller Court,” 24 Am. J. Legal Hist. 189 at 208, 21, 213 (1980).