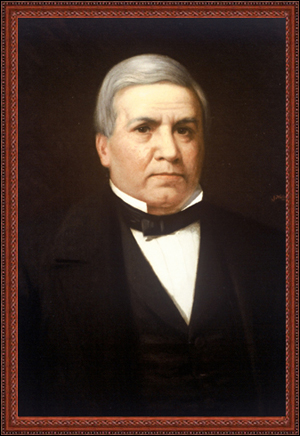

In a memorial address honoring Judge William B. Wright, poet and lawyer Alfred B. Street said of him: “His taste was cultured by much and varied reading, and he twined the fresh roses of literature with the dry lichens of the law. As a writer his style was beautifully concise and clear, his ideas showing through the clearness like objects through crystal water.”1 By all accounts, Wright appears to have been a self-made man who honorably served the public as a Surrogate, a delegate to the 1846 Constitutional Convention, an Assemblyman, a Justice of the State Supreme Court, and a distinguished Judge of the Court of Appeals, both as an ex officio and permanent member, and for a brief time, as Chief Judge.

William B. Wright was born in Newburgh, Orange County New York on April 16, 1806, to Samuel, a ship carpenter, and Martha (Brown) Wright. Wright’s mother died at an early age, when young Wright was still in his early teens. At thirteen, Wright worked in a bookstore and two years later became a printer’s apprentice. After his apprenticeship, he studied law with Ross & Knevals, leading members of the Orange County Bar at the time. A year after his admission to the bar in 1827, Wright was selected as editor of a short-lived Whig campaign journal, called “The Beacon.” In 1831, Wright moved to Goshen, Orange County, practiced law in the office of Samuel J. Wilkin, and served as an editor for the “Orange County Patriot,” later revived as the “Goshen Whig.” In 1834, Wright returned to Newburgh and opened a law office. In addition, he became an associate editor of “The Newburgh Telegraph,” a democratic newspaper, taking no part in its political writing, however. In 1835 or 1836, Wright again opened a law office, this time in Monticello. Around this time period, he was elected a justice of the peace in the Town of Thompson, and later, Surrogate of Sullivan County, serving from 1840-1844. Wright also continued to pursue his journalistic interests by contributing columns to the “The Sullivan County Whig.” Wright was elected to serve as a Sullivan County delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1846, and thus participated in the debates that reformed the New York State judiciary and created a new state high court where Wright would finish his career. As the Convention delegates debated the challenging and contentious issues of judicial reform (such as the merger of law and equity and the composition, method of selection, and terms of office for Court of Appeals Judges), Wright observed that one of the primary reasons for the convention was the “imperious necessity for judicial reform . . . [a benefit] expected by the people.”2 Wright also defended the debates’ length of time and range of topics, stating that whatever time spent on the

discussion of this great and important subject will not be wasted; nor will it be so regarded by those we represent. The people expect that upon this subject, more than upon all others, there shall be a full, frank and liberal exchange of sentiment, and that we shall approach it, not in the spirit of professional selfishness, nor with the contracted views of hostility towards an enlightened class of fellow citizens, but with minds . . . elevated above the influences of the meaner passions that cling to man in his best estate.3

After the Constitutional Convention, Wright was elected to the New York State Assembly and served from 1846 to 1847, resigning upon his election to a two-year term as Justice of the Supreme Court from the Third Judicial District. Although Wright’s career in the Assembly was short-lived, his name was submitted for Assembly Speaker, losing however, to William C. Hasbrouck of Newburgh in a close and spirited contest. Wright was eventually selected to chair the Assembly’s Ways and Means committee and spoke out on such issues as the location of the New York and Erie Railroad, and “school appropriation.”

Upon Wright’s election to the Supreme Court, he was immediately chosen to serve, along with fellow Supreme Court Justices Samuel Jones, Thomas A. Johnson, and Charles Gray, as one of the first ex officio judges on the newly formed Court of Appeals from 1847 to 1848, a post for which he was again selected in 1856 and 1860. In 1849, he was reelected to the Supreme Court, this time for an eight-year term, and again in 1857, filling an unexpired four-year term that arose upon the death of Justice Malbone Watson. On November 5, 1861, Wright was elected to a judgeship on the Court of Appeals, sitting on the Court until his death in 1868. Judge Wright briefly ascended to the position of Chief Judge on January 1, 1868, following the expiration of Chief Judge Henry E. Davies‘ term. Unfortunately, Wright held this position for only a few weeks as he died of kidney disease during the January 1868 term. During his time on the Court, Judge Wright penned several significant decisions, including Levy v. Levy (33 NY 97 [1865]) on charitable trusts and Sparrow v. Kingman (1 NY 242 [1848]), on estoppel in pais, but probably his most noteworthy writing was his concurring opinion in Lemmon v. The People (20 NY 562 [1860]), a pre-Civil War case dealing with the contentious issue of slavery.4

In that appeal (a case with facts similar to the infamous U.S. Supreme Court case of Dred Scott v. Sanford (60 US 393 [1857]), a Virginia slaveowner was served with a writ of habeas corpus as she passed through New York on the way to boarding a steamer for Texas. The writ alleged, that under New York law, her slaves must be freed. The writ asserted that Chapter 137 of the Laws of 1817, as amended in 1841, outlawed slavery in New York, and that any slave brought into the state would be freed. As the plain language of the law required the release of Lemmon’s slaves, the only issue on appeal was whether the statute was valid under the U.S. Constitution. Agreeing with much of Judge Hiram Denio‘s majority opinion, Judge Wright concluded that the state law was constitutional, holding that the state’s authority is derived from its power to determine a person’s status within their borders. Judge Wright opined that New York,

[a]s a sovereign State . . . may determine and regulate the status or social and civil condition of her citizens, and every description of persons within her territory. This power she possesses exclusively; and when she has declared or expressed her will in this respect, no authority or power from without can rightly interfere, except [in the case of fugitive slaves]; and in this, only because she has, by compact, yielded her right of sovereignty [in the Constitution].5

Thus, the Judge concluded that states have the “undoubted right to forbid the status of slavery to exist in any form, or for any time, or for any purpose, within her borders, and declare that a slave brought into her territory from a foreign State, under any pretence whatever, shall be free.”6 The Judge noted however, that such authority is not unlimited of course, and did not include the ability of states to change the status of citizens into slaves because “slavery is repugnant to natural justice and right, has no support in any principle of international law, and is antagonistic to the genius and spirit of republican government.”7 Lastly, although Judge Denio’s majority opinion failed to address the much criticized Dred Scott decision, Wright confronted it head on, stating that Dred Scott merely recognized “the exclusive right of the [State] to determine and regulate the status of persons within her territory . . . and all beyond this was obiter.”8

Although Judge Wright legalistically rejects all the asserted grounds for declaring the New York law unconstitutional, the language used indicates a personal antipathy to slavery. In fact, such a strong viewpoint may have been foreshadowed by the appearance of Judge Wright’s name, along with other state and local candidates, on a New York Times campaign advertisement during his 1861 Court of Appeals campaign, that was entitled “People’s Union Ticket,” and had a slogan “The Union Must And Shall Be Preserved.”9

Progeny

In 1846, Judge Wright married Martha Crissey of Monticello, New York, who predeceased him by ten years. The couple’s only child, Katherine, married Lieutenant-Commander La Rue Perrine Adams of Monticello, who died around the same time as Judge Wright. Both men were interred in one tomb in Kingston. Judge Wright also had one brother, George W. Wright and two known cousins, Captain William Wright of Newburgh and Alexander Wright of Goshen.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, Columbia Univ. Press (1985).

Browne, 2 Green Bag 277 (1890).

In Memoriam, 37 NY 693 (1868).

New York Times Advertisement, ProQuest Historical Newspapers, at pg. 5, November 1, 1861.

New York Times Obituary, ProQuest Historical Newspapers, at pg. 1, January 13, 1868.

Obituary, Republican Watchman Newspaper, January 1868 (exact date unknown).

There Shall be a Court of Appeals, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York (1997).

Published Writings

Beyond his decisions, we are unaware of any published writings by Judge Wright.

Endnotes

- In Memoriam, 37 NY 693 (1868).

- Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, Columbia Univ. Press (1985), at 27 (citing Proceedings, Constitutional Convention, 1846, ppg. 480).

- Id. at 480-481.

- For a more detailed discussion of the case, see the biography of Judge Denio in this volume.

- Id. at 616.

- Id. at 616-617.

- Id. at 617.

- Id. at 624.

- New York Times Advertisement, ProQuest Historical Newspapers, at pg. 5, November 1, 1861.