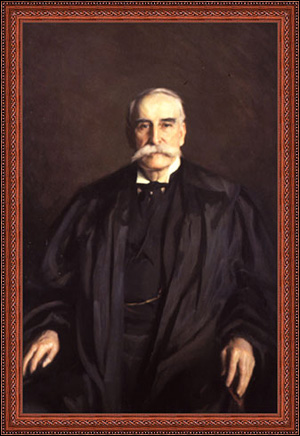

In 1913, William Sulzer, then Governor of New York, was put on trial for various charges relating to abuses of the powers and duties of the office of Governor. Edgar M. Cullen, Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, presided over Sulzer’s impeachment trial. The entire state turned its eyes to Albany to watch the drama unfold, but the star that met the public’s gaze was not Governor Sulzer or a lawyer trying the case. Rather, it was Chief Judge Edgar Cullen that commanded the attention of everyone at the trial. He presided over the impeachment trial with such dignity and presence that some watching the proceedings likened him to a king. One reporter described Chief Judge Cullen’s presence at the impeachment trial this way:

‘Like a king’ does not mean much to us who have known kings and such and found them to be mostly second rate or third rate [men] with a trick of wearing state clothes on occasion with manner, but pictorially it does very well describing a man with an outward dignity native and to the manner born.

With Edgar M. Cullen, it is truly something more than looks and bearing: it is the jurist of perfect balance and great and ready knowledge, great memory, quick perception, alert alike to forensic tricks and real points, distinctly, thrillingly alive in the present and profoundly versed in the past. . . .

The man so ‘like a king’ as he sits in his silken robes facing the Senate in the onyx chamber, when he stands on his feet is six feet tall or maybe an inch thereunder. His seventy years sit somewhat heavily on him. His eyesight is no longer the best. His hearing is somewhat impaired. His gait is not what it was . . . but by and large the first and last impression that he gives sitting there is one of dignity, clearness, sincerity – the upright Judge, with all that the phrase implies of power to get at the truth and courage to recognize it.1

William Sulzer is lucky indeed to have his case before such a presiding Judge, whatever the outcome must be. Nothing in his favor will be lost for want of keen perception by that master mind among the judges who assist the State Senate in trying the case.2

In the end, the outcome for Sulzer was an unpleasant one. The Court of Impeachment voted 43 to 12 to remove Sulzer from office. All of the Judges on the Court of Appeals, except Chief Judge Cullen, voted for Sulzer’s removal. Throughout the proceeding, Chief Judge Cullen vigorously denounced Sulzer’s actions, but voted against impeachment because the misconduct charged was not attributable to Sulzer’s official conduct as Governor and, thus, not a proper basis for impeachment. To protest the conviction, Chief Judge Cullen refused to be present during the final vote in the trial.

Presiding over Sulzer’s impeachment trial was one of the greatest challenges that Judge Cullen would face in his judicial career. The atmosphere of the Court at that time was one of constant political feuding and yet, Judge Cullen’s impartiality and learned rulings went unchallenged. His great knowledge of the law, as he applied it to the novel questions that arose during the trial, won him the praise of the State and the Nation. He displayed the same dignity and grace that defined his 33-year judicial career, knowing that the Sulzer trial would, in many people’s minds, mark the end of that career. The Sulzer trial came to a close in October 1913 and Judge Cullen was mandated by the constitution to retire, at age 70, in December of that year. The retirement marked the end of a highly distinguished judicial career that began in Brooklyn, New York – where Judge Cullen’s story begins and ends.

Life Before the Bench

Edgar Montgomery Cullen was born in Brooklyn, New York, on December 4, 1843, to Doctor Henry James Cullen, one of the most eminent physicians of Brooklyn, and Eliza McCue, sister of Judge Alexander McCue of Brooklyn. Judge Cullen had four sisters-Margaret, Charlotte, and Mary Elizabeth, and Countess Caroline de Valle, of Madrid, Spain. He also had an older brother, Henry James Cullen, Jr., a lawyer and leader of the Democratic party in Brooklyn.

Edgar Cullen was raised in a nice section of Brooklyn, inhabited mostly by the well to do business men of New York and their families. Every morning the men of the area crossed the Wall Street ferry, while the ladies looked after their mansions. Edgar and his brother and sisters played with the children of the other families of the elite. However, Edgar Cullen’s father had emigrated to America from Ireland as a child, and Henry Cullen Sr. instilled a reverence for democracy in his children.

Edgar was a bright child, and after he was out of primary school, his parents sent him to prepare for college at the famed Kinderhook Academy. He excelled at Kinderhook and, after mastering the advanced grades there, attended Columbia College. He graduated from Columbia College in 1860, at age 17. He then studied civil engineering at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York.

When the Civil War broke out, Edgar Cullen immediately joined the Union Army as a volunteer and was commissioned as second lieutenant in the First United States Infantry. He was in armed combat, including the battles of Corinth and Farmington. In 1862, President Lincoln and Governor Morgan commissioned Edgar Cullen as colonel of the Ninety-sixth New York Volunteers, making Cullen-at age 19-the youngest colonel in the entire Union Army. He served in the Union Army until 1863, when he received a serious hip injury during battle. The injury left him with a slight limp that would stay with him throughout his life. After the injury, he returned to Troy, New York to complete his civil engineering studies at the Polytechnic Institute. He also received a graduate degree from Columbia University in 1863. Edgar Cullen officially resigned his command from the Union Army in 1865.

After finishing his schooling in civil engineering, Edgar Cullen aided in the building of the South-Side Railroad, now the Montauk Point Branch of the Long Island Railroad. However, Cullen soon found himself bored in that field. His uncle McCue suggested that he try the field of law instead. Cullen took his uncle’s advice, began studying law in his uncle’s law office and was admitted to the New York State bar in May 1867. He established a successful private practice as a partner in the firm of McCue, Hall & Cullen, reorganized in 1870 as Hall & Cullen. In 1872, at age 29, he was appointed Assistant District Attorney in Kings County and served in that capacity until 1875. That year, Governor Tilden appointed Cullen to his staff as engineer-in-chief with the rank of brigadier general.

Cullen’s Judicial Career

Judge Cullen’s judicial career began in 1880, when as a Democrat, he was elected to the position of Supreme Court Justice for the second judicial district of New York. Judge Cullen soon attracted attention for his courage, honesty, and impartiality. One famous example of Judge Cullen’s courage on the bench is when he issued an injunction against John Y. McKane – “The Czar of Coney Island.” In 1893, McKane and his followers had been interfering with the poll watchers, in an attempt to fix the elections in the Borough of Gravesend-a notoriously politically corrupt area. Judge Cullen issued an injunction against McKane and his followers to desist from interfering with the poll watchers and the elections. McKane replied, “[I]njunctions don’t go here” as he tore up the injunction.3 McKane eventually got his just desserts and went to Sing Sing Prison. The subsequent reform cleaned up politics in the Borough of Gravesend.

A famous example of Judge Cullen’s impartiality and tenacity came in 1894, when he presided over the trial of Martin Hughes, William C. Schriener and Thomas Hughes, Inspectors of Election in the Fourth Election District of Southfield. The three were charged with ejecting a Republican poll watcher from the polling place. Due to rampant political corruption, the public expected an acquittal-Martin Hughes was a prominent member of the Democratic General Committee. However, Judge Cullen was determined to run a fair trial, and that included insuring that the jurors were not corrupted. He insisted that the trial be completed on the night it was given to the jury, even though the case did not go to the jury until 11 p.m. Further, because the location of the trial had no hotel to speak of, no telegraph office, was two miles from a railroad station, and had no telephones (as lightning had burned them out), Judge Cullen, the court officers, witnesses, and the attorneys camped out in the courtroom for the night. Shortly after midnight, the jurors returned with a guilty verdict. This guilty verdict paved the way for more guilty verdicts and pleas from various members of the Democratic Party.

However, Judge Cullen did not experience a backlash from his own party. Rather, when he was up for re-election in 1894, Judge Cullen’s popularity was so widespread he was nominated by both parties. When accepting the Republican nomination, Judge Cullen again displayed his unflinching honesty, stating:

That I am a Democrat, you all know. That party faith may influence a judge in the decision of principles which are cardinal doctrines of his party, may well be. Nay, I go further; such should be the case; otherwise the profession of political faith would be mere political hypocrisy. But in the application of those rules of justice, honesty, and fairness, which people of all parties hold alike-aye, even in the application of those principles are party tenets-certainly the judge should know no distinction between man and man, or party and party, but award according to his light the same justice to each.4

Given Judge Cullen’s widespread popularity, it was no surprise that when the four Appellate Departments were created in 1896, New York’s Governor Levi Morton appointed Judge Cullen to the Second Department’s bench. Judge Cullen faithfully served the Second Department until he was appointed to the Court of Appeals, as an auxiliary judge, by Governor Theodore Roosevelt in 1900. This appointment was made pursuant to an amendment to the State Constitution authorizing the Governor, upon the request of the Court of Appeals, to appoint up to four Justices of the Supreme Court to serve temporarily as members of the Court of Appeals. In 1904, when Alton B. Parker resigned as Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, to run for President of the United States, Judge Cullen won the nomination for the Chief Judgeship from both the Republican and Democratic parties. In 1904, Governor Odell appointed Judge Cullen to the position of Chief Judge. Chief Judge Cullen served on the Court of Appeals until his retirement in December 1913, which was mandated by the constitution because of his age.

During his years of service on the Court of Appeals and on the bench, Judge Cullen had a reputation for having a remarkable capacity to dispatch whatever business was before him efficiently, together with the highest quality of knowledge of the law. He is said to have had a remarkable memory, and it was not unusual to see him turn from the consultation table at the Court of Appeals to select a report and turn to a page where there was a decision supporting his position. One of his colleagues at the Court of Appeals remembers an incident when Chief Judge Cullen, during a particularly difficult legal discussion, slapped the consultation table and exclaimed to his colleagues “back to the books!”5

Judge Cullen was also said to employ a “military touch” to clear the Court of Appeals’ calendar. During the round table discussions of cases, Chief Judge Cullen would open the record of a case and ask the designated Judge to discuss it. At the slightest sign that the Judge had done only a cursory examination of the case, Chief Judge Cullen would slam the record shut and move on to the next case. In this way, the Judges were encouraged to put forth perpetual effort to clear the calendar without sacrificing quality. However, Judge Cullen softened this “military touch” with a constant courtesy and helpfulness that won him the adoration of his colleagues. Alton B. Parker said of Chief Judge Cullen:

It would not be just to say that Judge Cullen could write a more carefully balanced opinion than Judge Vann, a stronger one than Judge O’Brien, a more comprehensive brief opinion than Judge Landon or one expressed in more delightful English than Judge Werner. Nor could it be said that he had a larger command of cases which had come before him than Judge Haight, whose service on the Bench covered forty-two years, nearly all of which was in an Appellate Court. It is, however, his just due to say that considering every element which contributes to the making of a great Judge, he had no superior in that Court, nor was any member of it more greatly beloved by his associates than he.6

But it was not just his colleagues on the bench that respected his legal accomplishments. Judge Cullen received honorary law degrees from Harvard, Columbia, and Union Universities. He was also a respected member of many professional and social associations, including the Brooklyn Bar Association, the Lawyers Club, the Hamilton Club, the Brooklyn Club, and the University Club of New York.

As for his personal life, Judge Cullen spent his years on the bench carrying for his mother and sisters. Judge Cullen never married and, according to the New York Sun, never made time for romance.7 He chose the quiet, private life that he deemed befitting a public figure, even though he may have preferred a more social arrangement. General George W. Wingate, a close friend of Edgar Cullen, had this to say about the Judge’s life:

After getting up in the morning he would look over a newspaper, and eat a frugal breakfast, then examine any papers which had been submitted to him, hear those lawyers who called to see him on legal subjects, go to court and stay there from ten o’clock until half-past four or five, take a ride on horseback in the park in the late afternoon, eat a simple dinner and spend his evening working in his library upon cases which he had to consider, or reading law reports… In consequence, from his getting up in the morning until going to bed at night, his life was one continuous legal grind, only broken by an occasional brief fishing or shooting trip in the vacation season. These customs have continued much in the same way during his service in the Court of Appeals…

his life was not in accordance with his natural inclination. Judge Cullen is a genial man who loves the society of his friends; has a keen sense of humor, likes to fish and shoot and enjoys all things in moderation. The almost hermit’s life he has lived was not followed by him because it was pleasant, but because he considered it to be his duty and so considering it, he has adhered to it without regard to how it might affect him personally.8

Judge Cullen did not live his life of “one continuous legal grind” for lack of opportunity to leave it. His skills were so widely recognized that he was offered many opportunities to leave the bench for other positions. In 1893, he was allegedly offered the Collectorship of the Port of New York by Hugh McLaughlin. When asked about whether he would accept the lucrative position, Judge Cullen replied “Nothing on earth could persuade me to accept the office. I am satisfied where I am and intend to stay there as long as the people will let me. I have not sought the Collectorship, do not want it, and will not have it.”9

President Grover Cleveland also offered Judge Cullen a Cabinet position as Attorney General of the United States of America. Judge Cullen declined that position as well. It was also rumored that Judge Cullen was seriously considered by President Cleveland as a candidate for the United States Supreme Court. However, Judge Cullen saw his usefulness in the state judiciary and stayed there as long as he was allowed.

After the Bench

After retiring from the bench, Edgar M. Cullen re-entered private practice, becoming a member of the firm Cullen & Dykman, with offices in Brooklyn, New York. Judge Cullen, who had always been careful about publicly expressing his personal political opinions, became an outspoken proponent for the preservation of individual rights and was vehemently opposed to the national prohibition movement. He spoke out against, what he saw as, the decay of individual liberties in America through the over-interference of government. At an address to the New York Bar Association, which was later published, Judge Cullen stated “I am frank to admit that having been brought up in the then substantially universally accepted faith in the maxim that ‘Who is governed least is governed best’ it is hard for me, at my age, to divest myself of my early predilections.”10 Judge Cullen was also anti-suffragist, believing that women had no place in the political arena.

In early May 1922, at age 78, Edgar Cullen suffered a stroke, from which he died, three weeks later, in his Brooklyn home. Edgar M. Cullen, always caring for his sisters, left them a small fortune of approximately $500,000. His memorial service was attended by a notable gathering of jurists, public officials, and men prominent in civic and professional life. In Brooklyn, New York, they gathered to say farewell to “the man who was born to be a Judge, just as Emerson was born to be a poet.”11

Progeny

Judge Cullen never married and had no progeny.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Brooklyn Bar Association, New York Times, Feb. 28, 1901 in ProQuest Historical

Newspapers.

(Chadbourne/Electronic Book/Justices of the Supreme Court-Edgar M. Cullen [accessed July 28, 2005]).

Clarke, The Master Mind at the Impeachment Trial of Governor Sulzer, New York Sun, Sept. 28, 1913.

Collectorship of New York, New York Times, June 6, 1893 in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Columbia University General Catalogue, 126 (1912 ed).

Cullen, The Decline of Personal Liberty in America, 48 Am L Rev 345, 346 (1914) in HeinOnline.

Cullen in Parker’s Place, New York Times, Sept. 18, 1904, in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Edgar M. Cullen, New York Herald Tribune, May 24, 1922; Edgar M. Cullen Jurist, Dies at 78, New York Times, May 24, 1922.

Election Inspectors Found Guilty, New York Times, May 30, 1894 in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Governor Names Judges, New York Times, Jan. 2, 1900, in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

History of the Bench and Bar of New York (various editors) 1897.

In Memoriam, 239 NY 637-641 (1925).

Judges Cullen and Werner, 66 Alb L J 311 (1904-1905) in HeinOnline.

Judge Cullen Dies at Home in 79th Year, Brooklyn Times, May 23, 1922.

Judge Cullen Left Fortune To Sisters, New York Times, June 1, 1922, in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Legal Notes, 64 Alb L J 373 (1902-1903) in HeinOnline.

Memorial Address in Honor of Edgar M. Cullen, delivered by Alton B. Parker at The Lawyers Club, June 6, 1922.

Obituary of Henry J. Cullen, Jr., New York Times, Mar. 8, 1892, in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Removal Vote Does Not Bar Sulzer from Holding Future Office, New York Times, Oct. 13, 1913 in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Review of Probate Practice, 8 Queen’s L J 337 in HeinOnline.

Wingate, The Honorable Edgar Montgomery Cullen, Bench and Bar News Series, Jan. 1914, Vol 7, No. 3.

Published Writings Include:

The Case Against National Prohibition: Interview given to George MacAdam and Published at New York Times Magazine, Feb. 28, 1918 and New York Times, Feb. 24, 1918.

Man Is For Justice, Woman For Mercy: Letter to the New York Times, Sept. 3, 1915.

The Decline of Personal Liberty In America: Address delivered to the New York State Bar Association and Published at 48 Am L Rev 345 (1914) in HeinOnline and American Liberty in Danger, Declares Judge Cullen, New York Times, Feb. 8, 1914 in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

The People and the Law: Address Delivered at the Nineteenth Annual Meeting of the Maryland State Bar Association, July 1914.

Endnotes

- Clarke, The Master Mind at the Impeachment Trial of Governor Sulzer, New York Sun, Sept. 28, 1913.

- Id.

- Edgar M. Cullen, New York Herald Tribune, May 24, 1922; Edgar M. Cullen Jurist, Dies at 78, New York Times, May 24, 1922.

- History of the Bench and Bar of New York (various editors) 1897.

- Collectorship of New York, New York Times, June 6, 1893 in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Review of Probate Practice, 8 Queen’s L J 337 in HeinOnline.

- Memorial Address in Honor of Edgar M. Cullen, delivered by Alton B. Parker at The Lawyers Club, June 6, 1922.

- Clarke, The Master Mind at the Impeachment Trial of Governor Sulzer, New York Sun, September 28, 1913.

- Wingate, The Honorable Edgar Montgomery Cullen, Bench and Bar News Series, Jan. 1914, Vol 7, No. 3.

- Cullen, The Decline of Personal Liberty in America, 48 Am L Rev 345, 346 (1914) in HeinOnline.

- Brooklyn Bar Association, New York Times, Feb. 28, 1901 in ProQuest Historical

Newspapers.