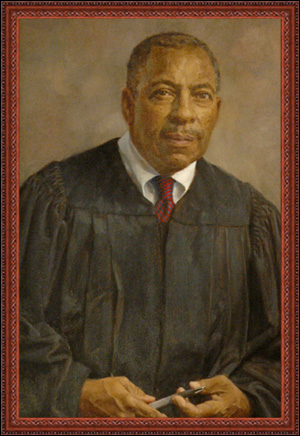

George Bundy Smith, the 101st Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals, is only the third African American ever appointed to serve on New York State’s highest court. Judge Smith was appointed to the Court of Appeals by Governor Mario C. Cuomo and was confirmed by the Senate in September 1992.

Years later, Judge Smith’s tenure on the Court of Appeals would be described as follows:

George Bundy Smith is widely acknowledged to be the most independent and dauntless voice on New York’s highest court. His opinions are known by close observers to be consistently the most fair and forthright and wise to issue from the Court of Appeals. Those who have had the privilege to work with him, learn from him, or otherwise spend time in this company know Judge Smith as extraordinarily gentle, generous, gracious, considerate, refined, humble, and yet bold, courageous and principled – in short, an utterly decent and admirable jurist and man . . . For many years, Judge Smith has been the most prolific author of dissents on the New York court . . . They reveal a judge committed to fundamental fairness, decency, equity, equality, the rule of law, and good (often times uncommon) common sense.1

[Judge Smith’s ] deep and abiding passion for justice is matched only by his passion for hard work to secure it . . . His several hundred opinions for the Court of Appeals are characteristically thoughtful and lucid, the product of his prodigious effort to reach the just result and express it precisely, clearly and convincingly.2

Early Years

Judge Smith was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1937 to Reverend Sidney R. Smith, Sr., and Beatrice Bundy Smith, a teacher and government worker, who greatly influenced her children. He was raised in racially segregated Washington, D.C. with his twin sister Inez, and older brother Sidney, Jr. The experience of growing up in a society where the color of one’s skin determined, among other things, where you lived, went to school, and what public accommodations you could use, left an indelible impression upon young George. He vividly remembers that the schools designated for ‘white students only’ had beautiful lawns, current text books, working science lab equipment, and athletic facilities. The schools designated for ‘colored’ students did not enjoy these same circumstances or benefits.

Judge Smith’s lifelong commitment to hard work and academic excellence had its genesis in the D.C. public schools. His grade school efforts resulted in receiving a full scholarship to the prestigious Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts for his high school education. Judge Smith was the only African American in his class. He graduated from Phillips Academy in 1955 and attended Yale University, where he was one of four African American students in a class of one thousand. While attending Yale, Smith studied in Paris, France, and received a Certificate of Political Studies from the Institut d’Etudes Politiques in 1958. He graduated from Yale in 1959. Judge Smith was an active participant in the civil rights movement and, indeed, his life was shaped by it. When he graduated from Yale, it was the early years of the movement. Inspired by the great Thurgood Marshall, counsel for the victorious plaintiffs in the landmark school desegregation case, Brown v. Board of Education,3 and future first African American United States Supreme Court Justice, Smith decided to embark upon a legal career. He applied to Yale Law School and at his urging Inez also applied. They were both admitted and graduated in 1962. Remarkably, by 1995, Smith and his twin sister, now Judge Inez Smith Reid, would be sitting on the highest state appellate courts in New York and the District of Columbia, respectively.4

In May 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized Freedom Rides on buses to the segregated south to advocate integration of bus, rail, and air terminals as prescribed by recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions. The Freedom Riders were black and white men and women who rode buses in nonviolent protest of the south’s Jim Crow laws. White mobs stoned and fire bombed some of the buses and beat many of the Freedom Riders; local police did nothing to protect them. John Lewis, future Congressman from Georgia, was one of the Freedom Ride leaders who was beaten and arrested. Smith responded to the call from Yale Chaplain Dr. William Sloane Coffin, Jr., to join the Freedom Rides even though he was in the midst of law school exams. George Smith, Reverend Coffin, Reverend Wyatt T. Walker, Reverend Ralph David Abernathy and others on this historic mission were arrested and convicted for sitting down and ordering coffee at a bus terminal lunch counter after some in the group had purchased tickets to ride from Montgomery, Alabama to Jackson Mississippi. In 1965, their convictions were overturned by a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court.5 George Smith and the Freedom Riders were represented by Professor Louis H. Pollak of Yale Law School, a federal judge in years to come, with the assistance of attorneys from the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. These outstanding attorneys included Constance Baker Motley, one of the chief legal strategists for the desegregation cases and the first African American female federal judge, Jack Greenberg, Director-Counsel, and James M. Nabrit, III.

Despite the danger around him during the Freedom Ride, Smith, true to his legendary quiet and calm nature, continued to study for his law school exams. It has been reported that when Rev. Coffin marveled and asked Smith how he could be studying at a time like that, Smith grinned and stated, “sticks and stones can break my bones but law exams will kill me.”6 This was an early example of Judge Smith’s self-effacing humor, and his determination always to be prepared and never to waste a precious moment. Today, anyone familiar with Judge Smith will attest to the fact that he is never without his briefcase, stuffed with work, whether on the subway or at a family gathering. Moreover, his colleagues on the court will further attest that Judge Smith is indeed always prepared.

Legal Career

After law school, Smith was determined to use his legal skills to right the wrongs of segregation. His career began at the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. There, he spent a lot of time in Alabama and Georgia, and tried a range of civil rights cases including school desegregation and demonstration cases. One of his most significant experiences involved drafting appellate briefs in the successful effort led by Ms. Motley to gain the admission of James Meredith to the University of Mississippi.

Smith’s next legal positions were as law secretary to three outstanding jurists: Civil Court Judge Jawn Sandifer (1962-1964), a former civil rights’ attorney; Supreme Court Justice Edward Dudley (1967-1971), the first African American ambassador; and the Honorable Harold A. Stevens, Presiding Justice, Appellate Division, First Department(1972-1974) and the first African American to serve on the Court of Appeals (Interim Appointment 1974). These experiences were critical to Judge Smith’s professional development.

In 1974, instead of continuing as Judge Stevens’ law secretary at the Court of Appeals in Albany, New York, Smith accepted the position of Administrator of Model Cities for New York City. Model Cities was a federally funded program developed as a part of the Johnson Administration’s War on Poverty to improve the quality of life in urban areas.

In May 1975, Judge Smith was appointed to an interim term on the Civil Court by New York City Mayor Abe Beame. In November 1975, Judge Smith was elected to the Civil Court, where he was assigned to the Family Court, Criminal Court, and as an Acting Justice of the Supreme Court. Judge Smith was later elected to the Supreme Court where he sat from January 1980 to December 1986. Governor Cuomo then appointed him to the Appellate Division, First Department where he served as an Associate Justice from January 1987 until his appointment to the Court of Appeals in September 1992. His term will expire in September 2006.

Judge Smith, a member of the New York and District of Columbia bars, continued his pursuit of knowledge and excellence by obtaining graduate degrees at New York University (MA, 1967 and PhD, 1974) and the University of Virginia Law School (Graduate Program for Judges – Master’s Degree in the Judicial Process, 2001).

Despite the demands of the judiciary and his personal endeavors, Judge Smith has remained committed to contributing to the education of lawyers. Since 1981, he has been an Adjunct Professor of Law at Fordham University Law School, teaching courses in New York Criminal Procedure. He has also taught at New York Law School and Baruch College.

Professional Associations and Community Service

Judge Smith has always been a leader. He is a role model and mentor to attorneys and judges of all stripes but most particularly for African Americans. Judge Smith is a staunch advocate for increasing the diversity of the bar and the bench. He unceasingly urges African Americans to become attorneys and to seek judgeships. Judge Smith believes that it does improve the quality of our judicial system when that system reflects the people it is serving and that differing life experiences and perspectives are critical to obtaining justice. To achieve these goals, Judge Smith believes that there must be organizations that have this focus. For that reason, he has been actively involved in many professional organizations. He served as President of the Harlem Lawyers Association. In 1984, the Harlem Lawyers Association and Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant Lawyers Association merged to form the Metropolitan Black Bar Association (MBBA); Judge Smith is one of the founders of the MBBA. Judge Smith served as the MBBA Chairman of the Board (1984-1988) and is currently a Board Member (1988-present). He is also a member of the Judicial Friends, a New York City organization of predominantly African American judges, and the Association of the Bar of the City of New York (Vice President, May 1988 – April 1989). In the past, Judge Smith held memberships with the Judicial Council of the National Bar Association and the New York County Lawyers Association.

In further service to the profession, Judge Smith was a Commissioner of the New York State Ethics Commission for the Unified Court System from 1989 – 2001.

Ever tireless, Judge Smith’s other community activities include membership in these organizations: Harlem Dowling-Westside Center for Children and Family Services (Board of Directors); One Hundred Black Men; Grace Congregational Church (Chairman of the Board of Trustees, 1980-present); Horace Mann-Barnard School (Trustee, 1977-1999); and Phillips Academy (Trustee, 1986-1990, and Alumni Council). Judge Smith’s work at Grace Congregational Church is especially important to him because he believes that churches are crucial to helping youngsters, providing housing and otherwise improving the lives of people.

Honors and Awards

Throughout his career, Judge Smith has been the recipient of numerous honors and awards. Only a few will be noted here. In May 2004, Judge Smith was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Law Degree from Fordham Law School for his years of dedication and excellence in teaching at that institution.

In 2005, the Albany Law Review, State Constitutional Commentary, was dedicated to Judge Smith. Articles of tribute were submitted by John D. Feerick, Professor and former Dean of Fordham Law School, the Honorable Judith S. Kaye, Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York, the Honorable Inez Smith Reid, D.C. Court of Appeals, and Kenneth G. Standard, then President of the New York State Bar Association.7

In November 2005, the Judicial Friends honored him at their annual Rivers, Toney, Watson Dinner with the Lifetime Achievement Award for his “dedication to scholarship and commitment to fairness and equality.”8 Judge Smith, a man noted for using few but always well chosen words, accepted the award “in the name of all those who struggled and struggled and struggled so that one day African Americans could sit where I am and could sit in other places.” He told his audience that, “[t]he fight [for diversity on the bench] is not over . . . those of you who sit here must continue. African Americans have got to be prepared to take the tough cases and to put in time, time, and time, until you solve that problem.”9

In December 2005, the New York County Lawyers Association (NYCLA) presented Judge Smith with the William Nelson Cromwell Award for his service to the profession and the community. NYCLA “was founded in 1908 as the first major bar association in the country that admitted members without regard to race, ethnicity, religion or gender.”10

Significant Opinions and Dissents

Judge Smith is a prolific writer, on and off the bench. He has authored hundreds of decisions while on the Court of Appeals, as well as during his tenure on the Appellate Division. The following is a brief survey of his most significant Court of Appeals opinions and dissents.

In People v. Wesley (83 NY2d 417 [1994]), the Court of Appeals addressed the admissibility of DNA profiling evidence and concluded that the evidence was properly admitted against the defendant in that case, under Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923). Judge Smith, authoring the majority opinion, set forth general guidelines to determine the admissibility of DNA evidence, and held that DNA evidence meets the Frye test for admissibility because “such evidence has been accepted and found reliable by the relevant scientific community.” 83 NY2d at 420. The Court further concluded that a proper foundation for the evidence had been made at trial.

In People v. Benevento (91 NY2d 708 [1998]), the Court of Appeals tackled the weighty issue of the constitutionally guaranteed right to the effective assistance of counsel. Following a conviction of second robbery, the defendant appealed, arguing that he did not receive a fair trial because he was denied the right to effective counsel. The Appellate Division reversed the conviction and, on appeal, the Court of Appeals reversed, concluding that the defendant had received “meaningful representation.” 91 NY2d at 709. The Court determined that in New York State the standard for ineffective assistance of counsel was not the same standard as in Strickland v. Washington which held that a reviewing court must determine that counsel made an error and the defendant was prejudiced by that error, and that there is a reasonable probability that the result of the case would have been different but for that error. Rather, in Benevento, the Court held that the New York courts will consider the fairness of the process as a whole to determine if counsel’s representation was meaningful or denied the defendant a fair trial.

In People v. Calabria (94 NY2d 519 [2000]), the Court addressed whether prosecutorial misconduct had deprived the defendant of the opportunity for a fair trial. In that case, the trial court had denied the People’s request to order the defendant to turn over a photograph of a police lineup because the chain of custody had not been preserved. Disregarding the lower court’s ruling, the People asked defense counsel for photographs of the lineup in the presence of the jury. In addition to other objectionable prosecutorial tactics, the People implied during closing arguments that defense counsel had tried to keep the photos of the lineup from the jury. Judge Smith wrote for the Court’s majority that, while each instance of misconduct on its own may not have prejudiced the defendant’s rights, the “cumulative effect of such conduct substantially prejudiced defendant’s rights.” 94 NY2d at 523.

In Local Gov’t Assistance Corp. v. Sales Tax Asset Receivable Corp., (2 NY3d 524 [2004]), the Court addressed the constitutionality of N.Y. Public Auth. Law ‘ 3240(5) (the “MAC Refinancing Act”) under N.Y. Const. art. VII, ’11, N.Y. Const. art. VIII, ‘2, and N.Y. Const. art. I, ‘ 10. By way of background, during the 1970s, the New York State Legislature created the Municipal Assistance Corporation (MAC) which issued bonds to finance New York City’s debt. To pay the debt service, MAC received a portion of state sales tax revenue. In the early 1990’s, as part of a fiscal reform program, the State created the Local Government Assistance Corporation (“LGAC”) to distribute State sales tax revenue and issue bonds as funding for various public services. Establishing a “trapping mechanism,” under the fiscal reform program, LGAC was required to certify to the State Comptroller and Commissioner of Taxation and Finance its debt service and financial requirements each year and the Comptroller was prohibited from distributing any State sales tax revenue until LGAC received the moneys requested. In 2003, the New York State Legislature enacted the MAC Refinancing Act, redirecting the portion of the State sales tax revenue to New York City so that the City could finance the remainder of the MAC debt by issuing new bonds through a public benefit corporation called the New York Sales Tax Asset Receivable Corporation (“STARC”). The MAC Refinancing Act also required LGAC to make annual payments to the City, which the City then assigned to STARC for the purpose of paying the debt service on the newly issued bonds. The LGAC refused to participate in the STARC transaction, challenging the constitutionality of the MAC Refinancing Act on both state and federal grounds. The Court held that the financing scheme did not circumvent the appropriation requirement because the payments to the City were the product of a valid legislative appropriation, as the clear legislative intent was for the State to appropriate the funds to LGAC. The Court further concluded that the City was not required to pledge its faith and credit because it owed no legal obligation to STARC or its bondholders should LGAC fail to make its payments to STARC. Finally, the Court held that the Act did not impair the rights of LGAC bondholders under U.S. Const. art I, ’10 because the Act did not subordinate the rights and obligations of the LGAC bondholders to those of STARC bondholders.

In a direct appeal pursuant to N.Y. Const. art VI. ‘ 3(b) and N.Y. Crim. Proc. Law ‘ 450.70, the Court, in People v. LaValle (3 NY3d 88 [2004]), addressed the constitutionality of the State’s death penalty statute. LaValle was convicted of first degree murder in the course of first degree rape. With a sharply divided Court, Judge Smith authored the majority opinion that upheld the defendant’s conviction but vacated the death sentence and remitted the case to the Supreme Court for re-sentencing.

On appeal to the Court, the defendant raised a number of issues regarding both the guilt phase and the penalty phase, from the onset of jury selection through the prosecutor’s summation, which the defendant argued merited reversal. With regard to the defendant’s guilt, the Court held, “defendant’s guilt was established beyond a reasonable doubt, and that the verdict of guilt was not against the weight of the evidence.” 3 NY3d at 102. Thus, the Court found that the errors proffered by the defendant amounted to harmless error, which did not warrant reversal.

With regard to the penalty phase of the defendant’s trial, however, the defendant challenged the constitutionality of CPL 400.27(10), which required the trial court to instruct jurors that if they failed to reach a unanimous decision on a sentence of death, the Court would impose a sentence of imprisonment for a minimum of 20 to 25 years and a maximum sentence of life in prison. Judge Smith wrote that the instruction was unconstitutional and thus, “under the present statute, the death penalty may not be imposed.” 3 NY3d at 131. The Court reasoned that the instruction created “the unacceptable risk that. . . .may result in a coercive, and thus arbitrary and unreliable sentence.” 3 NY3d at 120. The Court explained that juries might be pressured to agree to a death sentence out of the fear that the court would impose a lesser and more lenient sentence making the convicted killer eligible for parole.

In Courtroom Television Network LLC v. State of New York (5 NY3d 222 [2005]), the Court tackled the constitutionality of N.Y. Civ. Rights Law ’52 under the Federal and State Constitutions, which purportedly prohibited audio-visual coverage of most courtroom proceedings. The plaintiff argued that the statute denied it the right of access to trials guaranteed by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution and art. I, ‘ 8 of the New York State Constitution. Holding that “Civil Rights Law ’52 is constitutional under both the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, and article I, section 8 of the New York State Constitution” (5 NY3d at 234), the Court concluded that neither the Federal nor the State Constitutions guaranteed the media the right to televise court proceedings. Thus, because the press had access to the courtrooms and was free to report on the proceedings without cameras, the statute did not violate the First Amendment of the State and Federal Constitutions.

Never afraid to go against the majority on thorny legal issues, Judge Smith has authored many dissenting opinions during his tenure on the Court. For example, Judge Smith was the lone dissenter in People v. Parris (83 NY2d 342 [1994]), a case concerning the denial of an order suppressing evidence seized pursuant to a warrantless arrest. In that case, the defendant was apprehended by the police after a 911 report of a burglary during which a description of the defendant was relayed to officers by the 911 caller. The majority held that the prosecution failed to prove probable cause because the caller’s thin physical description of the burglar indicated that his account was conclusory and without a factual basis. Judge Smith disagreed, asserting that, because the 911 call specified both that a person had entered the premises and offered the intruder’s description, the arresting officer could have reasonably inferred that the basis of the informant’s information was personal observation.

In Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. State of New York (86 NY2d 307 [1995]), the Court of Appeals held that the plaintiffs had properly stated a cause of action under the Education Article of the New York State Constitution. The complaint alleged that the State’s educational financing scheme failed to provide students in New York City with a sound basic education. Subsequently, in Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. State of New York (100 NY2d 893 [2003]), the Court of Appeals determined that the plaintiffs had established their case that the funding scheme violated the Education Article. The case was remanded for further proceedings including a determination of how much funding was necessary for New York City schools. Judge Smith joined the majority but in a concurring opinion, stated that the remedy should be statewide and should include a revision of the present formula for allocating school funds.

In Johnson v. Pataki (91 NY2d 214 [1997]), the issue was separation of powers in state government and the bounds of executive authority. On March 21, 1996, Governor George Pataki issued Executive Order No. 27, pursuant to Art. IV, ‘ 3 of the New York Constitution and Executive Law ‘ 63, ordering the Attorney General to replace Bronx District Attorney Robert T. Johnson in a possible capital case against Angel Diaz, an alleged killer of a police officer, because of Johnson’s alleged “blanket policy” against the death penalty. The Executive Order stated that Johnson’s policy violated the District Attorney’s statutory duty to determine death penalty eligibility on a case-by-case basis and also raised the possibility that future death sentences would be challenged on proportionality grounds.

Johnson and Bronx County voters and taxpayers challenged the legality of the Executive Order in separate Article 78 proceedings. Supreme Court dismissed these petitions, holding that the superseder was a valid action authorized by statute and was nonjusticiable, and that the Governor’s action was justified by the District Attorney’s public “blanket policy.” Subsequently, the Attorney General charged Diaz with first degree murder and announced his intention to seek the death penalty. During appeal to the Appellate Division, Diaz committed suicide. The Appellate Division concluded the appeal was not moot despite Diaz’ death and affirmed the trial court’s decision. The Court of Appeals affirmed, holding that (1) mootness did not apply because the decision would still affect the remaining parties, and (2) the Governor’s power to supersede the District Attorney was properly grounded in Executive Law ‘ 63(2). Judge Smith dissented, disagreeing with the Court on both points.

Although Judge Smith acknowledged the Governor’s general authority to supersede a District Attorney, he stated that the Governor does not retain “unfettered and unreviewable discretion” (91 NY2d at 238) in the exercise of such power, and concluded that action under Executive Law ‘ 63(2) is subject to rational basis scrutiny. Judge Smith further emphasized the District Attorney has a constitutional, statutory, and common-law prosecutorial authority to determine whether and how to prosecute a criminal matter, and raised significant concerns about an unconstitutional intrusion by the executive branch on legislative power.

In People v. Tortorici (92 NY2d 757 [1999]), the Court addressed the trial court’s role in ordering a competency hearing under Criminal Procedure Law 730. The defendant Tortorici held a classroom of University of Albany students hostage and was indicted on fifteen counts of assault, kidnapping and several other charges. After a psychiatric examination, the defendant was declared unfit to stand trial. Following two months of psychiatric treatment, the defendant was certified fit for trial and convicted on all counts.

During pre-trial proceedings, the defendant insisted that he be absent from his own trial. Moreover, in response to the defense’s claim that the defendant was not responsible due to mental disease or defect, a court-appointed psychiatrist examined the defendant and concluded that he was unfit to stand trial but that he clearly understood the charges against him and the purpose of the proceedings. The trial court accepted the report but ruled the defendant fit to stand trial, based, in part, on its personal observations of the defendant.

In the Court of Appeals, the defendant argued that the trial court abused its discretion in failing to order a separate competency hearing, sua sponte. The majority affirmed, ruling that the trial court did not abuse its discretion. Judge Smith dissented, concluding that the People failed to meet its burden of proving the defendant’s competency by a preponderance of the evidence. Judge Smith focused on the defendant’s numerous psychological problems, as well as the court-appointed psychiatrist’s evaluation that the defendant was unfit to stand trial. Judge Smith also took issue with the trial court’s reliance on personal observations of the defendant’s competency, questioning whether the trial judge had any meaningful interaction with the defendant on which to base these observations after the defendant’s waiver from the pre-trial hearings and trial, particularly since the record lacked any evidence of further contact.

The two separate appeals in In re Muhammad F. (94 NY2d 136 [1999]) arose out of separate motions to suppress evidence against a juvenile and adult passenger, stemming from their arrests by plainclothes officers driving unmarked cars during a nighttime “safety check” of livery cabs. The officers in both cases were members of the New York City Taxi-Livery Task Force, created to combat rising levels of violent crime against cab drivers. The Task Force did not have any written procedures for the “safety checks,” but had oral instructions to stop a percentage of vehicles “in a set basis and not just arbitrarily.” (94 NY2d at 140.) In both instances, Appellate Division held the evidence was the result of an unconstitutional seizure and ordered the evidence suppressed.

The Court of Appeals affirmed, applying Brown v. Texas (443 U.S. 47 [1979]). The Court recognized the strong public interest in protecting livery cab drivers from violent crime but held that there was no evidence that roving (instead of fixed) checkpoints were an effective means of advancing that interest or that less intrusive methods were unavailable to the police. Judge Smith dissented, concluding that a police procedure stopping every third cab to check the driver’s safety was reasonable and not arbitrary. In light of the serious violent crime problem against taxi drivers, he maintained the State’s interest in protecting drivers outweighed “the individual’s interest in being free from governmental interference.” (94 NY2d at 152, quoting People v. John BB, 56 NY2d 482, 487 (1982).)

A deeply divided Court considered whether a plaintiff could maintain a claim for negligent inflection of emotional distress based on the ministerial acts of one of New York City’s medical examiners in Lauer v. City of New York (95 NY2d 95 [2000]). The principal issue was whether the City owed a duty to the plaintiff where the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) erroneously determined the cause of death of an infant, causing the police to launch a homicide investigation with the plaintiff, the child’s father, as the main suspect. Although a subsequent examination revealed the error, the medical examiner failed to correct the death certificate or notify the authorities and the family of the proper cause of death. When a newspaper exposé 17 months later revealed the medical examiner’s omission, the plaintiff learned, for the first time, of the OCME’s error, but not before the plaintiff endured 17 months of police investigation, divorce, and ostracism from his community. The plaintiff sued the City and the medical examiner for negligent infliction of emotional distress.

On appeal, the majority refused to impose a duty on the OCME that would run to the public at large, stating that the OCME owed a statutory duty only to the district attorney, not the plaintiff in this case. The Court also stated that no “special relationship” existed between the father and the OCME.

Judge Smith dissented, concluding that the OCME owed the plaintiff a duty once the medical examiner learned his original characterization of the boy’s death as a homicide was erroneous. At that point, according to Judge Smith, it was foreseeable to the medical examiner that a prudent exercise of reasonable care necessitated his communication of this evidence to the proper parties, and there was a violation of NY City Charter ‘ 557[g], which requires the OCME to “‘promptly deliver to the appropriate district attorney copies of all records relating to’ [the child’s] death.” (95 NY2d at 110.) Judge Smith further concluded that liability also flowed from the “special relationship” between the plaintiff and the City because (1) the OCME’s possession of the body created an affirmative duty to accurately determine cause of death, (2) the OCME knew that their failure to report exculpatory evidence to the police would damage the plaintiff, (3) the unique circumstances of the case called for a broad view of “direct contact,” and (4) the plaintiff justifiably relied on the defendant’s finding of cause of death because the OCME was the only one who could legally perform the autopsy.

The Court of Appeals in Horn v. New York Times (100 NY2d 85 [2003]) addressed the at-will employment doctrine in New York in deciding whether the New York Times could discharge its employee, a physician, because she refused to act unethically. The plaintiff sued the Times for wrongful termination and the newspaper moved to dismiss the claim under the at-will employee doctrine. The Appellate Division affirmed Supreme Court’s dismissal of the motion, fashioning a new exception to the at-will doctrine for physicians who are retaliated against by their employers for acting ethically. The Court of Appeals rejected this exception and dismissed the claim.

In his dissent, Judge Smith concluded that the at-will exception should apply to the plaintiff, likening the relationship between the plaintiff and her employer to the three “unique factors” of the lawyer-law firm relationship relied on by the Court when crafting the at-will exception in Wieder v. Skala (80 N.Y.2d 628 [1992]). Judge Smith rejected the majority’s characterization of the plaintiff as corporate manager, holding that “she was [not] hired to do anything but perform as a physician.” (100 NY2d at 101.)

Legal Publications

Judge Smith’s many legal publications include “You Decide! Applying the Bill of Rights to Real Cases,” a text for high school students coauthored with his wife, Dr. Alene L. Smith.

His law review articles reflect two subject areas that are of special interest to him: constitutional and criminal law. For example, in Prenatal Drug Exposure: The Constitutional Implications of Three Governmental Approaches (2 Seton Hall Const. L.J. 53 [1991]), Judge Smith and Gloria M. Dabiri, a former Law Clerk to Judge Smith and now a New York State Supreme Court Justice, examine the three approaches adopted by courts and administrative agencies to deal with the mother who gives birth to a drug-addicted or drug exposed child, and discuss the constitutional issues raised by each approach. In Police Encounters with Citizens and the Fourth Amendment: Similarities and Differences Between Federal and State Law (68 Temp. L. Rev. 1317 [1995]), Judge Smith and Janet Gordon, a former Law Clerk to Judge Smith, examine some of the similarities and differences between the guidelines of the United States Supreme Court and those of the highest courts in various states in the areas of police approaches to citizens on the street and beyond the curtilage of a home. In The Multimember District: A Study of the Multimember District and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (66 Alb. L. Rev. 11 [2002]), Judge Smith examines the concept of the multimember district with respect to the dilution of African American voting strength. He also authored or revised many publications in the law.

Progeny

Judge Smith married Dr. Alene L. Smith (nee Alene Lohman Jackson) August 22, 1964. She is a retired Hunter College Professor. The Smiths have two children, George Bundy Smith, Jr., ESPN journalist, and Beth Beatrice Smith, a college instructor.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Albany Law Review, Vol. 68, No. 2 (2005).

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Judicial Friends Honors ‘A Quiet Hero’: Associate Justice George Bundy Smith, Elizabeth Stull, published online Dec. 8, 2005, www.brooklyneagle.com.

New York County Lawyers Association, 2005 William Nelson Cromwell Award Recipient Associate Judge George Bundy Smith, http://www.nycla.org.

Published Writings Include:

Books and Treatises

George Bundy Smith, Chapter 15, Appeals to the New York State Court of Appeals, New York Civil Appellate Practice, New York Practice Series (2005), and revisions.

George Bundy Smith and Janet A. Gordon, revision of Chapter 55: Appeals Generally, Weinstein, Korn and Miller, New York Civil Practice (1996)

George Bundy Smith, revision of Chapter 26: Appeals, Weinstein, Korn and Miller, CIVIL PRACTICE LAW AND RULES MANUAL, Matthew Bender (1995).

George Bundy Smith and Janet A. Gordon, Chapter 48: Appeals to the Court of Appeals, Haig, et al., COMMERCIAL LITIGATION IN NEW YORK STATE COURTS, VOL. III, West’s NY Practice Series (1995).

Jay C. Carlisle and George Bundy Smith, revisions of New York Civil Practice: 1995 Jurisdiction: Sanctions and Professional Responsibility, Practicing Law Institute Litigation and Administrative Practice Course Handbook Series.

Jay C. Carlisle and George Bundy Smith, Introduction to New York Civil Practice: 1994 Jurisdiction; Venue; Consolidation and Severance; Sanctions, Practicing Law Institute Litigation and Administrative Practice Course Handbook Series.

Jay C. Carlisle and George Bundy Smith, Introduction to New York Civil Practice: 1993 Jurisdiction, Venue, Consolidation and Severance, and Sanctions, Practicing Law Institute Litigation and Administrative Practice Course Handbook Series.

George Bundy Smith and Alene L. Smith, YOU DECIDE! APPLYING THE BILL OF RIGHTS TO REAL CASES (1992).

Law Reviews and Journals

George Bundy Smith, The Multimember District: A Study of the Multimember District and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 66 Alb. L. Rev. 11 (2002).

George Bundy Smith, Choosing Judges for the State’s Highest Court, 48 Syr. L. Rev. 1493 (1998).

George Bundy Smith and Janet A. Gordon, The Admission of DNA Evidence in State and Federal Courts, 65 Ford. L. Rev. 2465 (1997).

George Bundy Smith and Gloria M. Dabiri, The Judicial Role in the Treatment of Juvenile Delinquents, 3 J.L. & Pol’y 347 (1995).

George Bundy Smith and Janet A. Gordon, Police Encounters with Citizens and the Fourth Amendment: Similarities and Differences Between Federal and State Law, 68 Temp. L. Rev. 1317 (1995).

George Bundy Smith and Gloria M. Dabiri, Prenatal Drug Exposure: The Constitutional Implications of Three Governmental Approaches, 2 Seton Hall Const. L.J. 53 (1991).

George Bundy Smith, The Standard of Conduct Required of Defense Attorneys and Prosecutors, 39 Brook. Bar. 99 (1988).

George Bundy Smith, Swain v. Alabama: The Use of Peremptory Challenges to Strike Blacks from Juries, 27 How. L.J. 1571 (1984).

Jawn Ardin Sandifer and George Bundy Smith, The Tort Suit for Damages: The New Threat to Civil Rights Organizations, 41 Brook. L. Rev. 559 (1975).

George Bundy Smith, The Failure of Reapportionment: The Effect of Reapportionment on the Election of Blacks to Legislative Bodies, 18 How. L.J. 639 (1975).

Addresses

George Bundy Smith, Voting: The Challenge to Democracy, delivered at Howard & Iris Kaplan Memorial Lecture, Hofstra University School of Law on February 2, 2005.

George Bundy Smith, State Courts and Democracy: The Role of State Courts in the Battle for Inclusive Participation in the Electoral Process, delivered at Brennan Lecture at New York University School of Law on March 2, 1999. Printed in 74 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 937 (1999).

George Bundy Smith, An Unfinished Struggle, delivered in commemoration of African-American History Month at Court of Appeals Hall on February 16, 1996, Printed in N.Y.L.J., February 21, 1996, at 2, col. 3.

Endnotes

- Vincent Martin Bonventre, Editor’s Foreward, State Constitutional Commentary, 68 Alb. L. Rev., No. 2 (2005).

- Judith S. Kaye, A Passion for Justice, State Constitutional Commentary, 68 Alb. L. Rev. 211 (2005).

- 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

- As of this writing, elder brother Sidney, Jr., has retired from a distinguished career as a biochemist and is attending divinity school.

- Abernathy v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 447 (1965).

- Inez Smith Reid, From Birth to the Bench: A Quiet but Persuasive Leader, State Constitutional Commentary, 68 Alb. L. Rev. 215 (2005).

- State Constitutional Commentary, 68 Alb. L. Rev., No. 2 (2005).

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Judicial Friends Honors ‘A Quiet Hero’: Associate Justice George Bundy Smith, Elizabeth Stull, published online Dec. 8, 2005, www.brooklyneagle.com.

- Ibid.

- www.nycla.org.