1500s/1600s

1524

Giovanni da Verrazzano visits New York Bay

Giovanni da Verrazzano, an Italian explorer, becomes the first European to visit New York Bay. He arrives there while exploring the New World’s Atlantic coast at the behest of the King of France.

Giovanni da Verrazzano, an Italian explorer, becomes the first European to visit New York Bay. He arrives there while exploring the New World’s Atlantic coast at the behest of the King of France.

1609

Henry Hudson Anchors in New York Bay

The Half-Moon, captained by Henry Hudson and sailing under the Dutch flag, anchors in New York Bay. Hudson had been hired by the Dutch East India Company to help find a northeast passage that would provide a shorter route to India.[1]

The Half-Moon, captained by Henry Hudson and sailing under the Dutch flag, anchors in New York Bay. Hudson had been hired by the Dutch East India Company to help find a northeast passage that would provide a shorter route to India.[1]

[1] Ellis, David M., et al, A Short History of New York State, Cornell Univ. Press, 1957, p. 19.

1614

Albany Founded

Albany, then called Fort Nassau, is founded as a trading post.

1621

Charter Granted to the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch government grants a charter over the lands of New Netherland to the Dutch West India Company on June 3, 1621. “New Netherland” includes lands located on the east coast of North America between the Demarva Peninsula (including most of Delaware and portions of Maryland and Virginia) and southwestern portions of Cape Cod. It incorporates areas of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania. The Dutch West India Company is a commercial corporation chartered by the Dutch government to found colonies and develop sources of commerce on the African and North American coasts and in the West Indies. The Company is given a trade monopoly in the Americas[2] and is invested with comprehensive powers, including authority to employ soldiers and fleets; to build forts; to make treaties; to appoint governors and other public officers; and to take steps necessary to maintain order and administer justice.

[2] Ibid.

1623

New Netherland Colony Established

The New Netherland Colony is formally organized by the Dutch and a settlement is established in what later becomes known as Manhattan. The first colonial Director is Cornellis Jacobsen May, who serves for only a short period and is then succeeded by Willem Verhulst who, likewise, serves but a year or two.[3] At the time, the number of colonists is so small that there is no need for institution of any formal justice system.[4]

The New Netherland Colony is formally organized by the Dutch and a settlement is established in what later becomes known as Manhattan. The first colonial Director is Cornellis Jacobsen May, who serves for only a short period and is then succeeded by Willem Verhulst who, likewise, serves but a year or two.[3] At the time, the number of colonists is so small that there is no need for institution of any formal justice system.[4]

[3] The colonial directors are appointed by the Board of Directors of the Dutch West India Company. A council of four is created to assist each director – giving him advice, voting on local regulations, and serving as a court in those few instances where one is necessary. Ibid., p. 22.

[4] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, The Lawyers Co-Operative Publishing Company, 1906, p. 455.

1624

Fort Nassau Becomes Fort Orange

Fort Nassau (site of future Albany) becomes Fort Orange. It is the first permanent Dutch settlement in New Netherland, becoming home to some 34 Dutch families who had been recruited by the Dutch West India Company. A majority of these first settlers are Walloons, exiles from what is today Belgium. They are Protestants from part of the Netherlands then under the rule of Catholic Spain and they are seeking religious freedom in the new colony.[5]

[5] Shorto, Russell, The Island at the Center of the World, Random House (Vintage Books), 2004, pp 40, 45; Macy, Harry, Jr., The Original Families of New Netherland, New York Genealogical and Biographical Society (1999).

1626

Peter Minuit Becomes Director of New Netherland

Peter Minuit becomes Director of the New Netherland Colony. Such governmental authority for the Colony as is put in place is built on a Dutch model. Together with his council (including Dutch West India officials and two colonists), Minuit exercises all legislative, executive, and judicial powers in the Colony. Collectively, these officers are referred to as the New Netherland Court of Justice and their judicial authority extends to civil, criminal, and admiralty matters. And from 1629 on, following introduction of the patroon system in the Colony, the New Netherland Court of Justice also exercises appellate jurisdiction over decisions of the patroon courts and other local courts. Along with the Schout (an office, sometimes referred to as the Schout-Fiscal, that combines the powers of a prosecutor and a sheriff), these officers are subject to the appellate jurisdiction and supervision of Dutch authorities in Amsterdam.

Peter Minuit becomes Director of the New Netherland Colony. Such governmental authority for the Colony as is put in place is built on a Dutch model. Together with his council (including Dutch West India officials and two colonists), Minuit exercises all legislative, executive, and judicial powers in the Colony. Collectively, these officers are referred to as the New Netherland Court of Justice and their judicial authority extends to civil, criminal, and admiralty matters. And from 1629 on, following introduction of the patroon system in the Colony, the New Netherland Court of Justice also exercises appellate jurisdiction over decisions of the patroon courts and other local courts. Along with the Schout (an office, sometimes referred to as the Schout-Fiscal, that combines the powers of a prosecutor and a sheriff), these officers are subject to the appellate jurisdiction and supervision of Dutch authorities in Amsterdam.

1626

Minuit Purchases Manhattan Island

In November, Director Minuit purchases Manhattan Island from the Lenape Indians. While a myth persists that the purchase price was $24 worth of beads and other trinkets, the actual price is for 60 guilders worth of trade goods (or slightly more than $1,000 today).[6]

[6] As reported to the Directors of the Dutch West India Company by Peter Schaghen, a representative of the Dutch States General, following the arrival in Holland of a ship from New Netherland in the late summer of 1626. The present-day value of 60 guilders has been calculated by the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

1629

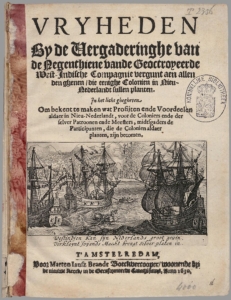

Dutch West India Company Grants Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions

On June 7, 1629, the Dutch West India Company grants a Charter of “Freedoms and Exemptions” (sometimes referred to as the Charter of “Privileges and Exemptions”), introducing the patroon system into the New Netherland Colony. In addition to providing land grants to the patroons, the Charter sets forth rules for the governance of their lands. These rules establish each patroon as chief magistrate of his lands.[7]

On June 7, 1629, the Dutch West India Company grants a Charter of “Freedoms and Exemptions” (sometimes referred to as the Charter of “Privileges and Exemptions”), introducing the patroon system into the New Netherland Colony. In addition to providing land grants to the patroons, the Charter sets forth rules for the governance of their lands. These rules establish each patroon as chief magistrate of his lands.[7]

[7] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, The Lawyers Co-Operative Publishing Company, 1906, p. 8. See also Scott, Henry, The Courts of New York State, Wilson Publ. Co., 1909, pp 329-332. While several patroonships were established in New Netherland, only one — Kilianen Van Rensselaer’s Rensselaerwyck — proved to be successful. The 1629 Charter. Of Freedoms and Exemptions, Historical Society of the New York Courts.

1631

New Netherland Receives New Directors

Peter Minuit is recalled to Holland. He is succeeded as Director of the Colony by Wouter van Twiller (1633) and then by Willem Kieft (1638). By the time Kieft arrives, New Amsterdam is a collection of 80-90 structures and perhaps 400 people. Principal colonial officials include Director Kieft, the provincial secretary, and the Schout-Fiscal. The Director makes the rules by fiat and, with his appointed council (consisting of two members of which he is one),[8] sits as a court to hear both civil and criminal cases brought by the Schout.

Peter Minuit is recalled to Holland. He is succeeded as Director of the Colony by Wouter van Twiller (1633) and then by Willem Kieft (1638). By the time Kieft arrives, New Amsterdam is a collection of 80-90 structures and perhaps 400 people. Principal colonial officials include Director Kieft, the provincial secretary, and the Schout-Fiscal. The Director makes the rules by fiat and, with his appointed council (consisting of two members of which he is one),[8] sits as a court to hear both civil and criminal cases brought by the Schout.

Kieft is a reckless and ineffective leader. The colonists react by demanding the establishment of judicial and municipal tribunals like those they had enjoyed in Holland. There, for more than a century, every town and village had had its own local tribunal. This tribunal combined the attributes of a court and a municipal government. It consisted of several magistrates (called the burgomaster [a kind of mayor], the schepens [a kind of alderman], and the schout [the prosecutor/sheriff]). While there was no formal system of popular representation, generally a town’s propertied individuals would annually elect men who then would choose the burgomaster and schepens. Kieft responds by creating a council of 12 men nominated by the colonists. This is the first popularly chosen body in what later becomes New York State.[9]

[8] Shorto, Russell, The Island at the Center of the World, p. 114.

[9] Ibid., p. 121.

1640

Second Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions Adopted

The Dutch West India Company adopts a further Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions for the New Netherland Colony. In part, this Charter expressly directs that the colonial Director (now being referred to as the “Governor”) and his council act as a court to determine all questions concerning the Company’s rights and all other complaints; and, also, that they act as an orphan’s and surrogate’s court (where they are to observe the customs of Amsterdam and the principles of Roman Dutch law)[10], and as judges in criminal and religious matters. Provision is also made for appeals from local tribunals to the Governor and his council from judgments for more than 100 guilders and from criminal sentences.[11]

[10] Setaro, Franklyn C., The Surrogate’s Court of New York: Its Historical Antecedents, 2 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. (1956), p. 286..

[11] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, pp 10-11.

1641

Adriaen Van der Donck Arrives at New Netherland

Adriaen Van der Donck arrives at New Netherland. Hired by the patroon Killian Van Rensselaer as a schout for Rensselaerwyck, Van der Donck becomes the first lawyer in the colony.[12]

[12] Shorto, Russell, The Island at the Center of the World, p. 103.

1647

Peter Stuyvesant Becomes Governor

Peter Stuyvesant becomes the colonial Governor, replacing Willem Kieft who had been recalled to Holland the previous year. Governor Stuyvesant establishes a court of justice to decide all civil and criminal cases, with himself as the presiding justice and the colonial Vice Director and two local citizens he selects to assist him. He also establishes a board of nine men to serve as a permanent advisory body[14] and to assist the court of justice by providing a source of arbitrators to whom civil cases might be referred.[15] This arbitral service reflects a common feature of Dutch jurisprudence. Decisions of the arbitrators (who serve in rotating panels of three) are binding on the parties to the affected proceedings, subject to appeal to the Governor and his council.

Peter Stuyvesant becomes the colonial Governor, replacing Willem Kieft who had been recalled to Holland the previous year. Governor Stuyvesant establishes a court of justice to decide all civil and criminal cases, with himself as the presiding justice and the colonial Vice Director and two local citizens he selects to assist him. He also establishes a board of nine men to serve as a permanent advisory body[14] and to assist the court of justice by providing a source of arbitrators to whom civil cases might be referred.[15] This arbitral service reflects a common feature of Dutch jurisprudence. Decisions of the arbitrators (who serve in rotating panels of three) are binding on the parties to the affected proceedings, subject to appeal to the Governor and his council.

The members of the tribunal of nine men are chosen by the Governor from 18 men selected by the colonists. This tribunal is created in response to continuing public discontent with the absence of popular government and provides a vehicle for some limited input from the colonists.

In 1649, Adrien Vander Donck, the first lawyer in the Dutch Colony, serves as the president of the nine men. A political activist, he is an antagonist to Governor Stuyvesant, leading disaffected colonists in efforts to campaign for representative government in New Netherland.

[14] Some regard this board as the first legislative government in New Amsterdam. See Lankevich, George J., New York City: A Short History, New York University Press, 1998, pp 12-13.

[15] Ellis, David M., et al, A Short History of New York State, Cornell Univ. Press, 1957, p. 24.

1650

Third Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions Issued

The Dutch governing body in Holland, the States-General, issues a revised Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions[16] and orders that a new court be established in the Colony consisting of a Schout, two Burgomasters, and five Schepens, all to be elected popularly. This order is a further response to continued colonial protests about the dictatorial management of the New Netherland Colony and to provide an effective forum for the adjudication of debts, especially those owed local merchants by the Dutch West India Company.[17] The Schout, Burgomasters, and Schepens Court mandated by the States-General is modeled after the judicial system in place in Holland.

When this court is first established by Governor Peter Stuyvesant in 1653, he determines to make all appointments to it.

Formally known as the “Worshipful Court of the Schout, Burgomasters and Schepens,” this court enjoys unlimited civil and criminal jurisdiction (in non-capital cases), and usually decides cases before it without a jury. It also acts at times as a court of admiralty and as a probate court (exercising jurisdiction over wills and the estates of widows and orphans).[18] While referred to as a “court” and effectively constituting the first regularly sitting formal court system for the Colony, the body also discharges executive and legislative responsibilities: although their duties are nominally judicial, the Schout combines the offices of a sheriff and a district attorney; the Burgomasters are like mayors; and the Schepens are like aldermen. At this point, New Amsterdam is still so small that sharp governmental divisions remain unnecessary.

On the civil side, the Court follows fairly simple procedures and makes frequent use of arbitrators chosen by the litigants or appointed by itself. On the criminal side, the Schout serves as a prosecutor.

Shortly after the Court is established in New Amsterdam, similar courts are set up in Breuklin (Brooklyn) and elsewhere on Long Island (in the area of the so-called “five Dutch Towns”).[19] Also, in 1652, Governor Stuyvesant, acting on his own prerogative, establishes a court in Albany that is independent of the patroon courts.[20]

From all these courts, appeal may be taken to the Governor and his council at New Amsterdam (the colonial seat).

[16] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, p. 12.

[17] Klein, Milton M. (ed), The Empire State: A History of New York, p. 99.

[18] Scott, Henry, The Courts of New York State, pp 333-340.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

1653

New Amsterdam Becomes a City

With the signing of a municipal charter, New Amsterdam becomes a city.

1655

Court of Orphan Masters Established

A separate court, the court of orphan masters, is created to exercise jurisdiction over matters involving orphans. This court, a forerunner of today’s Surrogate’s Court, is established because the Schout, Burgomasters, and Schepens Court is overwhelmed with the number of children orphaned during a recent Native American war in the Colony.

1657

Flushing Remonstrance Delivered to General Stuyvesant

The Flushing Remonstrance–a plea for religious toleration for Quakers in New Netherland–is delivered to Governor Stuyvesant following his imposition of a law against the hosting of Quaker missionaries in the Town of Vlissingen (later Flushing). The Remonstrance declares that the people of Flushing will not obey this law. It is an early, if somewhat incomplete, effort to recognize some liberty of conscience among the Dutch colonists; and it is regarded by many as a precursor of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

The Flushing Remonstrance–a plea for religious toleration for Quakers in New Netherland–is delivered to Governor Stuyvesant following his imposition of a law against the hosting of Quaker missionaries in the Town of Vlissingen (later Flushing). The Remonstrance declares that the people of Flushing will not obey this law. It is an early, if somewhat incomplete, effort to recognize some liberty of conscience among the Dutch colonists; and it is regarded by many as a precursor of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

Governor Stuyvesant, along with members of the Colony’s orthodox Calvinist clergy, does not react well to the Remonstrance. They spend the next four years trying to root out Quakerism in the English towns of Long Island.[21]

[21] Klein, Milton M. (ed), The Empire State: A History of New York, p. 86.

1664

Colonial Judicial Structure Expands

By this time, the Colony’s judicial structure consists of:

- The patroon courts;

- The Burgomaster, Schepens, and Schout Court in New Amsterdam;

- The Burgomaster knockoffs on Long Island, in Albany, Canorasset, and Middleburgh; and

- The Appellate Court of Amsterdam.

1664

New Netherland Becomes New York

The British seize New Netherland and rename it New York.[22] King Charles II, by royal patent, gives his brother James, the Duke of York and presumptive heir to the British throne, property rights granting him the entire Atlantic coast, from Maine to the Allegany Mountains and that portion bounded on the east by the Connecticut River and on the west by the Delaware River. Under this patent, James enjoys virtually unlimited authority, including plenary power to make laws provided they are not inconsistent with the common law of England.[23] To help implement this authority, he appoints Colonel Richard Nicolls to serve as colonial Deputy-Governor and his agent.[24]

The British seize New Netherland and rename it New York.[22] King Charles II, by royal patent, gives his brother James, the Duke of York and presumptive heir to the British throne, property rights granting him the entire Atlantic coast, from Maine to the Allegany Mountains and that portion bounded on the east by the Connecticut River and on the west by the Delaware River. Under this patent, James enjoys virtually unlimited authority, including plenary power to make laws provided they are not inconsistent with the common law of England.[23] To help implement this authority, he appoints Colonel Richard Nicolls to serve as colonial Deputy-Governor and his agent.[24]

The formal transfer of power from the Dutch to the British is effectuated through the Articles of Capitulation (or, as they are also known, the Articles of Surrender[25]). These Articles form the basis for Dutch surrender of the Colony. Their terms, agreed to between Peter Stuyvesant (who, thereafter, retires from public life) and Deputy-Governor Nicolls, provide that:

- Dutch colonists may, if they wish, return to Holland;

- Dutch colonists who wish to remain in New York may do so, and, if they do, continue to enjoy their own customs and rights to inheritance;

- Contracts made during Dutch rule will continue to be subject to Dutch law;

- Past judgments of Dutch courts may not be called into question;

- Inferior Dutch civil officers/magistrates may remain in office for the duration of their existing terms;

- All newly-selected magistrates must take an oath of allegiance to the British Crown; and

- Dutch colonists will enjoy liberty of conscience.[26]

At the time of Stuyvesant’s surrender to the British, New Netherlands consists of only about 8,000 colonists occupying small settlements on New York Bay and along the banks of the Hudson.[27]

[22] At the same time, New Amsterdam is renamed “New York” and Beverwijck is renamed Albany (recognizing that the James, the Duke of York, is also the Duke of Albany). Shorto, Russell, Taking Manhattan, W. W. Norton Pub. Co, 2025, p. 271.

[23] Ibid., p. 30.

[24] Nicolls is designated “Deputy-Governor”, and not “Governor”, because, as the new owner of the province, the Duke of York is technically the Governor. Shorto, Russell, Taking Manhattan, p. 271.

[25] Shorto, Russell, Taking Manhattan, p. 265.

[26] Ibid., p. 28. See also Chester, Alden, Courts and Lawyers of New York, A History: 1609-1925, Vol. I, p. 289.

[27] Ibid., p. 18.

1665

Duke’s Laws Ratified

The Duke’s Laws, delivered by James, the Duke of York, to Deputy-Governor Nicolls and intended to serve as New York’s first legal code, are ratified at a convention of delegates from each of 17 towns in the English-controlled areas of the Colony held at Hempstead, Long Island.[28] Although they were not formally excluded from the convention, there are very few Dutch delegates in attendance.[29] This is because there is a perception that Deputy-Governor Nicolls did not intend that the Duke’s Laws, although nominally framed for the governance of the entire colony, should supersede Dutch law in those areas; and that they should only apply in the formerly British-controlled areas (eastern Long Island and parts of Westchester).

The Duke’s Laws, delivered by James, the Duke of York, to Deputy-Governor Nicolls and intended to serve as New York’s first legal code, are ratified at a convention of delegates from each of 17 towns in the English-controlled areas of the Colony held at Hempstead, Long Island.[28] Although they were not formally excluded from the convention, there are very few Dutch delegates in attendance.[29] This is because there is a perception that Deputy-Governor Nicolls did not intend that the Duke’s Laws, although nominally framed for the governance of the entire colony, should supersede Dutch law in those areas; and that they should only apply in the formerly British-controlled areas (eastern Long Island and parts of Westchester).

The Duke’s Laws, which are based on English law, Roman-Dutch law, and the laws and regulations of Britain’s New England colonies,[30] provide for a new judicial organization in the province. This includes creation of the office of Justice of the Peace (commissioned for various towns) and institution of the following courts:

- A local court for each town to be held every few weeks by the town constable and the town’s overseers for the trial of small (under £5) civil actions. While these courts are provided in response to calls for self-government–the overseers are subject to popular election by freeholders–they can also be presided over by Justices of the Peace appointed by the Governor. Appeals from the judgments of these courts are to be taken to a Court of Sessions.

- A Court of Sessions originally for each of the three main three districts, or ridings (east, west, north), into which the Colony had been divided (the Towns of Long Island, Westchester, and Staten Island, respectively), but later also for New York City and plantations in the upper Hudson Valley. Meeting twice annually and presided over by all the Justices living in the riding, the Court of Sessions is the workhorse of the system, exercising non-capital criminal jurisdiction and civil jurisdiction in cases involving more than £5 but less than £20. All actions except those involving equity jurisdiction are to be tried by juries (comprised of the overseers of the towns in each riding). The Court of Sessions, which will sit continuously in New York until 1894,[31] also sits as a probate court, exercising jurisdiction today entrusted to Surrogate’s Court — provided that the Governor or one of his councilors should be present on such occasions. Appeals from judgments of a Court of Sessions can be taken to the Court of Assizes.

- A Court of Assizes (or General Assizes) for the entire colony. This court sits once annually in New York City in late October (although the Governor could call it into session more frequently) and is presided over by the Governor and his council, plus any of the provincial Justices of the Peace wishing to attend. The court is primarily an appellate forum to which appeals from all inferior tribunals can be taken but it also enjoys original jurisdiction of all cases, typically taking cognizance of equity cases, capital crimes, and civil actions involving more than £20. Notably, this Court exercises executive and legislative powers as well as judicial authority.[32]

In addition to establishing these courts, the Duke’s Laws empower the Governor to provide for a Court of Oyer and Terminer, presided over by judges that he names, to exercise jurisdiction over a capital case where the next sitting of the Court of Assize is more than two months away.

Notably, there is no provision for a formal Court of Chancery under the Duke’s Laws. All the established courts enjoy equity jurisdiction (to be exercised by their judges sitting without juries) within the limits otherwise applicable to them.

Finally, the Duke’s Laws also introduce the jury system in New York.

[28] Ibid. p. 30.

[29] See http://moglen.law.columbia.edu [Chapter 1. Beginnings 1664-1691, at pp 7-8].

[30] Scott. Henry Wilson, The Courts of the State of New York: Their History, Development and Jurisdiction (1909).

[31] Scott, Henry, The Courts of New York State, pp 347-352. The Courts of Sessions will be abolished under New York’s 1894 Constitution except in New York County, where it will continue to serve until its abolition in 1962.

[32] Ibid, pp 345-346.

1665

New Municipal System Established in NYC

In June 1665, Deputy-Governor Nicolls abolishes the remaining Dutch forms of government in New York, including the Court of Schout, Burgomasters, and Schepens in New York City.[33] At the same time, he establishes a new municipal system for the City — including a Mayor, Aldermen, and a Sheriff — in keeping with English custom. This new system includes a court to be known as the Mayor’s Court, the members of which are to be the Mayor, the Aldermen, and the Sheriff. This Court is to exercise civil jurisdiction. [34] At first, introduction of the Mayor’s Court is more a matter of form than substance. There is no radical departure from the Court of the Schout, Burgomasters, and Schepens except that regular trial by jury is introduced.[35] By and large, over the next several years, Dutch law continues to be followed.[36]

[33] Nelson, William E., Legal Turmoil in a Factious Colony: New York, 1664-1776, 38 Hofstra Law Rev., p. 19.

[34] Scott, Henry, The Courts of New York State, pp 341-344.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Over the next 156 years, however, the Mayor’s Court will serve as the Municipal Court for New York City. See Chester, Alden, Courts and Lawyers of New York, A History: 1609-1925, Vol. I, p. 336.

1667

Second Anglo-Dutch War Ends

The second Anglo-Dutch War ends with the Treaty of Breda pursuant to which the Dutch Republic formally cedes New Netherland to the British.

1673

Dutch Rule Restored to New York

There is a brief hiccup in British rule. Dutch warships sail into New York harbor and the British surrender to them whereupon Dutch rule is restored in the province. This proves to be but a brief restoration, however, as British rule returns the following year (1674) with the signing of the Treaty of Westminster (ending the third Anglo-Dutch War).

1674

British Rule Returns to New York, Andros Named Governor

With the return to British rule, Edmund Andros is named Governor of the province of New York. He commences negotiations for the handover of Dutch territories with the Dutch Governor, Anthony Colve. This handover takes place in late 1674. By its terms, existing property holdings are left undisturbed, and the province’s Dutch inhabitants are permitted to maintain their Protestant religion.

With the return to British rule, Edmund Andros is named Governor of the province of New York. He commences negotiations for the handover of Dutch territories with the Dutch Governor, Anthony Colve. This handover takes place in late 1674. By its terms, existing property holdings are left undisturbed, and the province’s Dutch inhabitants are permitted to maintain their Protestant religion.

The people of the colony call for a legislative assembly.[37]

[37] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, p. 27.

1678

Court of Admiralty Established

The Duke of York directs Governor Andros to establish a Court of Admiralty. This Court will not be a regularly sitting tribunal; rather, the Governor can call it into being on an ad hoc basis upon issuance of a special commission. Even with introduction of this Court, most admiralty matters are actually heard in the Mayor’s Court.

1681

Thomas Dongan Becomes Governor

Governor Andros is recalled to England. He is replaced by Thomas Dongan in 1682. It is a time of fiscal crisis and much discontent in the province. In his commission from the Duke of York, Governor Dongan is given responsibility for erecting such a court structure as he deems necessary, which structure should be operative until the Duke directs otherwise. Governor Dongan also is instructed to call a representative assembly. This is largely in response to widespread public unrest across New York and general resistance to the collection of import duties.[38]

Governor Andros is recalled to England. He is replaced by Thomas Dongan in 1682. It is a time of fiscal crisis and much discontent in the province. In his commission from the Duke of York, Governor Dongan is given responsibility for erecting such a court structure as he deems necessary, which structure should be operative until the Duke directs otherwise. Governor Dongan also is instructed to call a representative assembly. This is largely in response to widespread public unrest across New York and general resistance to the collection of import duties.[38]

[38] Ellis, David M., et al, A Short History of New York State, p. 32.

1683

New York’s Provincial Assembly Convenes

New York’s provincial Assembly is convened in October by Governor Dongan at Fort Amsterdam (or, as it is later known, Fort James), sitting at the southern tip of Manhattan near the present Battery. This body is empowered to pass laws subject to approval by the Governor and by the Duke of York.[39]

[39] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, p. 430.

1683

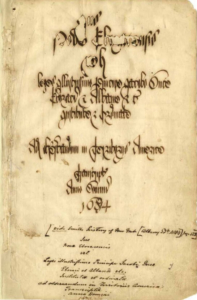

Assembly Adopts Charter of Liberties and Privileges

The Assembly adopts a Charter of Liberties and Privileges, which provides for religious toleration and outlines a form of government that, with minor modifications, remains in place until the American Revolution. Many have regarded this Charter, which closely resembled modern constitutions in form and substance, as New York’s original constitution.[40]

[40] Ibid., p. 433.

1683

Assembly Reorganizes Provincial Courts

Also in 1683, the provincial Assembly enacts “An Act to settle courts of justice”. This Act continues the office of Justice of the Peace while recognizing four distinct tribunals:

- A Town Court for each town for the trial of small (up to 40 s) causes but having no criminal jurisdiction.

- A Court of Sessions in each county to sit quarterly or half-yearly (except in Albany, where it is to sit three times each year, and in New York City, where it is to sit four times each year) and to have unlimited civil and criminal jurisdiction.

- A Court of Oyer and Terminer and General Gaol Delivery for the entire province to exercise both original and general appellate jurisdiction and to replace the Court of Assizes. There are two judges of this Court commissioned by the Governor each of whom, together with four local Justices of the Peace, is to hold a circuit of the court in every county in the colony twice yearly.

- A Chancery Court colony-wide to be held by the Governor or his council, with the Governor empowered to appoint a Chancellor to serve in his stead. Sitting bi-monthly and considered to be the highest provincial court, Chancery Court has jurisdiction over all matters in equity.

Governor Dongan makes only one change in relation to the act creating this court structure. He establishes a Court of Judicature (or Court of the Exchequer), which is to be held monthly by the Governor and his council for the purpose of determining suits or matters arising between the King and inhabitants of the province concerning lands, rents, rights, profits, and revenues.

1684

New York City Mayor and Aldermen Petition Governor Dongan

The New York City Mayor and aldermen together petition Governor Dongan for a City charter. They also request that the Governor and his council appoint a Recorder to serve as a judge and to assist the Mayor and the aldermen in managing the City. Governor Dongan complies with this last request and the Recorder presides over the City’s Court of Sessions.[41]

[41] Chester, Alden, Courts and Lawyers of New York, A History: 1609-1925, Vol. I, pp 413-414.

1684

Assembly Abolishes Court of Assizes

The Assembly abolishes the Court of Assizes. The Governor acts as Surrogate and he and his council constitute the Court of the Exchequer.

1685

James, Duke of York Becomes King James II

Upon the death of Charles II, the Duke of York becomes King James II of England. Henceforth, New York is no longer the private possession of a royal English subject but, instead, an American province of the Crown.[42] King James proceeds to veto the 1683 Charter of Liberties and Privileges approved by the provincial Assembly.

Upon the death of Charles II, the Duke of York becomes King James II of England. Henceforth, New York is no longer the private possession of a royal English subject but, instead, an American province of the Crown.[42] King James proceeds to veto the 1683 Charter of Liberties and Privileges approved by the provincial Assembly.

[42] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, p. 31.

1685

Governor Dongan Receives a New Commission

King James issues a new commission to Governor Dongan, retaining him in office with the title, “Captain General and Governor in Chief”.[43] No provision is made for a colonial Assembly. Under Dongan’s new commission, appeals in court cases can be taken to the Governor and his Council where the amount involved exceeds £100; and further appeal can be taken to the King and his Privy Council where the amount involved exceeds £300. The new commission also provides the Governor and his council with exclusive legislative power in the province; that exercise of this power is subject to approval by the King and his Privy Council; that the Governor may create courts of law or equity, as needed; and that the Governor is to appoint Judges and Justices of the Peace.

[43] Ibid.

1686

New York City & Albany Receive New Municipal Charter

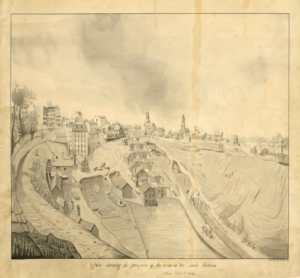

Governor Dongan grants New York City a new municipal charter, which, among its provisions, includes several modifying the local court structure. At the same time, Dongan grants a charter conferring municipal status upon Albany (for the next 100 years, or until 1785, Albany and New York City remain the only cities in New York). This Albany charter (referred to locally as the Dongan Charter) is almost identical to the one awarded to New York City.[44]

The most significant aspect of New York City’s new charter is its clear separation of the legislative and judicial functions. Before this charter, these functions had been combined in the City’s Mayor’s Court. Under the new charter, however, while the same officers will discharge both functions, they will do so in discrete settings. Also separated under the charter are civil and criminal judicial powers. The result is that there now are three tribunals for the City:

- A Common Council, in which the officers sit to discharge legislative duties;

- The Mayor’s Court (technically, a Court of Common Pleas, although it is popularly referred to at the time by its Dutch title, the “Mayor’s Court”), in which civil actions are tried; and

- The Court of Oyer and Terminer (and later the Court of Quarter Sessions) for the trial of criminal cases. In addition, the City’s new charter establishes a Court of Chancery and a Court of the Exchequer. [45]

Later, after the American Revolution and New York’s attainment of statehood, the Mayor’s Court will become the Court of Common Pleas for the City and County of New York.[46]

The new charter for Albany establishes the first municipal officers for the city (at that time, the northernmost outpost in the New York province), which include a mayor, a recorder, and two aldermen plus two assistant aldermen from each municipal ward. Together these officers comprise the Common Council, and all of them, except the assistant aldermen, exercise judicial powers along with their legislative authority.

[44] Ibid., p. 33.

[45] Chester, Alden, Courts and Lawyers of New York, A History: 1609-1925, Vol. I, pp 416 et seq. See also Scott, Henry, The Courts of New York State, pp 341-344.

[46] Scott, Henry, The Courts of New York State, pp 341-344.

1688

Andros Becomes Governor of the Dominion of New England

Governor Edmund Andros returns to New York two years following his appointment as Governor of the Dominion of New England. The Dominion is a short-lived union of English colonies in New England and the mid-Atlantic region. Before he is deposed, King James had ordered the inclusion of New York in that Dominion.

There is some evidence that changes in the Dominion’s judiciary, made two years before, may perhaps have been imported into New York upon its entry into the Dominion. These changes include institution of quarterly Sessions Courts to exercise criminal jurisdiction and inferior Courts of Common Pleas with very limited civil jurisdiction. There also is a Superior Court of Judicature, which has broad civil jurisdiction and limited appellate authority, and a Court of Chancery.

1689

Governor Andros Arrested Following Boston Revolt

In the wake of the so-called Boston Revolt — an uprising following King James’ deposition and sparked by public discontent with the administration of Governor Andros and English rule in the Dominion — Governor Andros is arrested and returned to England for trial. Shortly thereafter, Joseph Dudley, the Chief Judge of the Dominion, is likewise arrested and returned to England.

1689

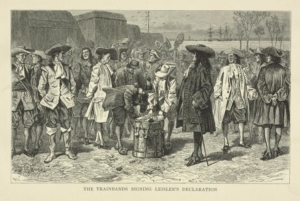

Leisler’s Rebellion Occurs

Andros’s deputy in New York, Francis Nicholson, is very unpopular. His delay in recognizing the new Protestant British monarchs, William and Mary, furthers local fears of a French invasion and that there is a plot afoot to restore Catholic power in New York. These fears lead to an insurrection and the informal formation of a Committee of Safety to defend the province against any invasion and Catholic efforts to destroy Protestantism in its territory. This Committee is headed by a wealthy merchant, Jacob Leisler, who earlier had served as a judge of the Admiralty Court and Justice of the Peace. Leisler declares himself to be the acting Lieutenant-Governor of the province. During his tenure (which comes to be known as Leisler’s Rebellion), New York’s representative assembly is reconstituted and other steps are undertaken to weaken the ruling oligarchy of patroons, merchants, and landlords for the benefit of the province’s lower classes.[47] Also, property is purchased to establish a French Huguenot settlement north of Manhattan, which later becomes the city of New Rochelle.[48]

Andros’s deputy in New York, Francis Nicholson, is very unpopular. His delay in recognizing the new Protestant British monarchs, William and Mary, furthers local fears of a French invasion and that there is a plot afoot to restore Catholic power in New York. These fears lead to an insurrection and the informal formation of a Committee of Safety to defend the province against any invasion and Catholic efforts to destroy Protestantism in its territory. This Committee is headed by a wealthy merchant, Jacob Leisler, who earlier had served as a judge of the Admiralty Court and Justice of the Peace. Leisler declares himself to be the acting Lieutenant-Governor of the province. During his tenure (which comes to be known as Leisler’s Rebellion), New York’s representative assembly is reconstituted and other steps are undertaken to weaken the ruling oligarchy of patroons, merchants, and landlords for the benefit of the province’s lower classes.[47] Also, property is purchased to establish a French Huguenot settlement north of Manhattan, which later becomes the city of New Rochelle.[48]

[47] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, p. 34. See also Wikipedia, “Jacob Leisler”, last edited 1/28/2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacob Leisler.

[48] Id.

1691

Henry Sloughter Becomes Governor

Governor Henry Sloughter arrives in New York. Sloughter, whose commission designates him as Captain-general and Governor-in-Chief of New York, immediately has Leisler arrested on a charge of treason. After trial by a special court of Oyez and Terminer, Leisler is convicted and sentenced to hang.[49]

[49] Ellis, David M., et al, A Short History of New York State, p. 35.

1691

Provincial Assembly Meets

Sloughter’s commission also authorizes him to call a provincial Assembly. This Assembly first meets on April 9, 1691. It proves to be the first permanent representative body in New York.[50] At this point, the province consists of fewer than 20,000 people.[51] The Assembly’s first major act is to enact a new Charter of Liberties recognizing the rights of people of the province and setting forth the manner of provincial government.[52]

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, p. 439.

1691

Assembly Enacts Statute to Organize the Province’s Courts

Prodded by Governor Sloughter, New York’s provincial Assembly enacts a statute prescribing the provincial court system. Entitled “An act for the Establishing Courts of Judicature for the Ease and benefitt of each respective Citty, Town and County within this Province”, this statute includes provisions creating a court structure that largely continues courts then in operation and that is in most respects generally modeled after the English court system.[53]

Of particular note is the fact that the new provincial court structure is the result of legislative action. Prior to this time, English tradition had uniformly dictated that court structures be decreed by the King and his subordinates. Sloughter’s commission as Governor exemplified this tradition, leaving creation of the provincial courts to him subject to specific directions that he not establish any courts that had not theretofore been created. Governor Sloughter, however, perhaps in response to public calls for more representative government, disregards his commission and, instead, recommends that the Assembly enact legislation erecting the provincial courts. The resulting statute provides for:

- Justice of the Peace Courts (to replace existing Town Courts). Presided over by lay people appointed by the Governor, these courts serve as the principal provincial courts. Ordinarily they sit individually, in panels of two or three Justices of the Peace, although occasionally — twice yearly in all counties except New York and Albany; four times yearly in New York City, where it is colloquially referred to as “Quarter Sessions”; and three times yearly in Albany — they sit together as a Court of Sessions. Individually, Justices of the Peace have power to try small civil cases (involving damages of up to 40 s) and certain criminal matters, and to enforce a wide variety of local administrative regulations (e.g., game laws, fire regulations, licensing ordinances). Also, where specially commissioned (in each county except Albany and New York), Justices of the Peace can sit as a Court of Common Pleas to hear civil matters. In less populated areas of the province, they also can be charged by the Governor to hold Courts of Common Pleas to hear probate and intestate succession cases — cases that might otherwise be heard by the Governor himself. Sometimes Justices sitting as a Court of Common Pleas can be joined by a Supreme Court Justice. When sitting as a Court of Sessions, Justices of the Peace exercise criminal jurisdiction — although they also can exercise criminal jurisdiction out of Sessions Court over relatively small criminal matters. Also, in the Court of Sessions, which is substantially modeled after the English Quarter Sessions’ Courts, Justices exercise executive, legislative, and administrative responsibilities. For instance, they oversee maintenance of jails, stocks, and whipping posts; discharge certain social welfare-related tasks like supervising the local overseers of the poor; and promulgate various regulatory ordinances (bearing on such matters of county concern as tax collections, liquor retailing, and, more generally, the morals, manners, health, and welfare of the community). Various laws adopted by towns must be confirmed in the Court of Sessions. From time to time, beyond their roles in and out of this Court, Justices will sit in Mayor’s Courts in Albany and New York City. These Courts are known as Courts of Common Pleas and they hear particular commercial cases.

Conferring civil jurisdiction over relatively small matters upon the provincial courts represents a significant departure from English practice, which then has no uniform system for handling such matters. Not so with criminal jurisdiction, where the provincial courts — in which Justices exercise broad powers — fairly well follow English institutions. - A Supreme Court of Judicature, to serve as the highest trial court of general civil and criminal jurisdiction in the province (general jurisdiction being understood to mean all the jurisdiction exercised by three distinct British trial courts, i.e., Kings Bench, Common Pleas, and Exchequer). This Court enjoys power to establish rules and ordinances, and to regulate practice before it. Originally established to sit only in New York City, the provincial Assembly soon changes the law so that, once each year, one of the Court’s Justices will ride circuit to hear cases around the province. This is done to accommodate litigants outside the City, who otherwise must bring witnesses and even jurors sometimes great distances so that they can have their cases tried before Supreme Court. When on circuit, a Justice is sometimes assisted by local Justices of the Peace. In all cases, however, a Justice may only conduct trials. Commencement of a lawsuit and filing of the pleadings therein still must be done in New York City; and, likewise, judgment in the case must be rendered in the City before the Supreme Court sitting there en banc. Occasionally, a Supreme Court Justice is required to preside over a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer and General Jail Delivery — in New York City, Albany, and sometimes elsewhere — to try persons who have been arrested and jailed between regular Supreme Court sessions. This Court of Oyer and Terminer should not be confused with the pre-existing Court of Oyer and Terminer, which had been established by the provincial Assembly in 1683. This 1691 Court becomes the criminal branch of Supreme Court while the original Court (which was presided over by two Justices commissioned by the Governor to ride circuit twice a year to hear civil and criminal cases and appeals) is abolished. To be sure, however, the Supreme Court, sitting en banc, does not hear many criminal cases. Those are most often heard by the circuit judges, in the Sessions Courts, or by Justices of the Peace.

Appeals from judgments of the Supreme Court are rare as the distances involved, and the related expense and delay, are prohibitive. There is provision, however, for appeals to the Governor in cases involving more than £100; and to the King of England in cases involving more than £300. There is no provision for appeal from Supreme Court in a criminal case, although occasionally, where exceptionally large fines are involved, appeal to the King is permitted.

There are originally five Supreme Court Justices (a Chief Justice plus four Associates also known as puisne justices) all of whom are appointed by the Governor. The first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature is Joseph Dudley, a native of Roxbury, Massachusetts. Ten years later, the number of Justices is reduced to three. The Justices of the Supreme Court hold office at the King’s pleasure. - A Court of Chancery consisting of the Governor and the Council (although the Governor could appoint a Chancellor to sit in his stead) to handle equity matters. In practice, however, this Court seldom sits. Instead, equity matters, along with other matters such as probate and intestate succession, generally are handled by other courts, including the Supreme Court of Judicature.

- A Court of Errors consisting of the Governor, the Council, and the principal judges to hear appeals in civil cases involving £100 or less. Where a greater amount is in controversy, appeal must be taken to the King and his Privy Council.

Beyond these statutory courts, there also is a Court of Admiralty — established by the Executive. This court does not sit very often because admiralty jurisdiction also lies in the Supreme Court and the Mayor’s Courts (dating from the era of Dutch rule), and those courts generally hear such admiralty cases as arise.

This court structure incorporates many of the main features of the Dominion Act. Most significantly, the structure ensures a significant degree of central control over the courts — by the appellate process it creates and through the broad jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

The statute establishing this court structure is effective for only two years but is renewed several times by the colonial Assembly, expiring finally in 1698.

[53] L. 1691, c. 4 (found in vol. 1 of the Colonial Laws of New York).

1692

Assembly Passes Act to Regulate the Probate of Wills

The provincial Assembly passes an act regulating the probate of wills and providing for the administration of intestate estates. The Assembly also directs that Supreme Court sit twice annually for New York and Orange Counties together, and once annually for all other counties. Further, it provides that a single Supreme Court Justice should “goe the circuit”, i.e., hold court while being assisted by two or more of the local Justices of the Peace in the county where court is being held.

Originally, the Duke’s Laws (ratified in 1665) had vested jurisdiction over decedent’s estates in the Courts of Sessions and the Mayor’s Court. Gradually, beginning during the tenure of Governor Nicolls (1664-1668), this jurisdiction was assumed by the Governor and, through his delegation (i.e., at his prerogative), by the Governor’s Secretary. Over time, this practice is continued, and the delegation becomes formalized to the point where, under Governor Sloughter, it is settled, and the institution of a prerogative office is made official. The Assembly’s 1692 enactment largely memorializes this practice, with the Governor’s delegate recognized as the Prerogative Court, except that, in more remote counties of the province, the Courts of Common Pleas can act to take proof of wills and transmit the record of their findings to the Prerogative Court. Also, the Assembly’s enactment authorizes the designation of freeholders in towns to take charge of the estates of those dying intestate. Ultimately, this class of officials takes the name “surrogate”, which title has survived to this day.

Introduction of circuit riding for the Supreme Court may have suggested a contemporary legislative intent to decentralize the Court. It is unclear, however, whether, in so doing, the Assembly was striving to make the Supreme Court into a county institution or merely into a circuit bench.

The Circuit Court’s criminal jurisdiction is exercised through commissions conveying distinct powers to the affected judges. An assize commission would give authority to the Circuit Judge to conduct trial; a gaol delivery commission would authorize the judge to deliver a defendant from jail for trial in a venue on the basis of indictments already found by a lower court of inferior jurisdiction; an oyer and terminer commission would require empanelment of a grand jury to return an indictment, which then could be tried. In combination, these instruments confer upon the circuit-riding judge all necessary original jurisdiction over felonies and misdemeanors.

1698

Governor & Assembly Engage in Power Struggle Over New York’s Courts

The original statute fixing the colonial court structure expires but, in the following year, the Assembly passes an act to revive it. Governor Bellamont, however, declines to approve this act.

These events play out during an ongoing power struggle between the Assembly and the Governor. Ostensibly, the failure to continue statutory authorization for the courts leaves the province without a lawful court system. But the Governor believes that, inasmuch as all of his predecessor’s commissions had included a general provision authorizing them to erect and establish courts, he, too, enjoys such authority. And, so, in May 1699, with this legal understanding and driven generally by the view that courts and their operations fall squarely within the King’s (and his delegates’) prerogative, and with his Council’s concurrence, the Governor by ordinance directs that all the courts previously established and continued until 1698 should be re-established. For many years thereafter, the provincial judiciary continues to exist by such executive fiat. The Governor’s ordinance also clarifies that Supreme Court should remain a centralized institution, situated in New York City; and that when single Justices sit outside the City, they are riding circuit.

Following its acts of 1691 and 1692, and the several acts of the later 1690’s continuing the 1691 court structure, the provincial Assembly is never again able to effect major revisions of New York’s court structures. It is not for want of trying, however. Throughout the 18th century, many efforts are made to change the courts but, in the main, they are rebuffed by the Governor and the Crown; and the Assembly is only able to affect operations in the lowest courts. Even there, the changes it makes are only modest. Any important changes made to the larger court structure and operations invariably are the result of ordinances issued by the Governor and his Council.

1700s

1701

Court of Chancery Established

English authorities order creation of a Court of Chancery, to be held monthly and presided over by the Governor and his Council. While such a court had been established by the provincial Assembly in 1691, it never sat. In 1701, however, there begins an extended period of debate and controversy in New York concerning Chancery’s use. The English government very much wants such a court to exercise jurisdiction over the Crown’s many claims for provincial revenue that are in arrears. At the same time, the public resists such claims and efforts to facilitate their collection. Indeed, the provincial Assembly quickly passes resolutions declaring the Court to be illegal. Over the ensuing decades, there will be a continuing tug of war on this issue.[55]

[55] See generally, NYS Court of Chancery, Historical Society of the New York Courts.

1702

Court of Chancery Suspended

The Court of Chancery is suspended by the Governor’s Council pending study and report by two Supreme Court Justices. It is revived two years later (1704) through exercise of the gubernatorial prerogative power.[56]

[56] Nelson, William E., Legal Turmoil in a Factious Colony: New York, 1664-1776, 38 Hofstra Law Rev., p. 25.

1704

Supreme Court’s Annual Terms Increases

The number of annual terms of the Supreme Court is increased to four.

1708

Court of Chancery Challenged

Local opposition to the Court of Chancery is renewed. The Assembly position is that, unless it has consented thereto, executive effort to create such a Court is ultra vires.

1712

Controversy Ensues as Governor Robert Hunter Becomes Chancellor

Governor Robert Hunter assumes the role of Chancellor. This action rekindles public disagreement over the King’s assertion of a prerogative to establish courts for the province. It leads to an Assembly resolution condemning the Governor’s action: “Resolved, That the erecting of a Court of Chancery without consent in general assembly is contrary to law, without precedent, and of dangerous consequence to the liberty and property of the subjects [and] That the establishing of fees, without consent in general assembly is contrary to law.” It is suggested that one of the root reasons for the strong provincial opposition to Chancery Court lies in the fact that many large landowners in New York — beneficiaries of significant land grants from Governors (who had incentive to sell lands, often as frauds on the crown, to boost their compensation through the fees they could collect upon these transactions) — are concerned that the legitimacy of their holdings could later be challenged in that Court.

Governor Robert Hunter assumes the role of Chancellor. This action rekindles public disagreement over the King’s assertion of a prerogative to establish courts for the province. It leads to an Assembly resolution condemning the Governor’s action: “Resolved, That the erecting of a Court of Chancery without consent in general assembly is contrary to law, without precedent, and of dangerous consequence to the liberty and property of the subjects [and] That the establishing of fees, without consent in general assembly is contrary to law.” It is suggested that one of the root reasons for the strong provincial opposition to Chancery Court lies in the fact that many large landowners in New York — beneficiaries of significant land grants from Governors (who had incentive to sell lands, often as frauds on the crown, to boost their compensation through the fees they could collect upon these transactions) — are concerned that the legitimacy of their holdings could later be challenged in that Court.

After deliberation of the issue in the Governor’s Council and consultation with London, the Governor continues to sit as Chancellor. The controversy remains, however, and persists for many years thereafter.

1727

Assembly Resolves that the Court of Chancery is Illegal

The Assembly passes a resolution declaring Chancery Court to be illegal. This action is likely inspired by the Assembly Speaker, Adolph Phillipse, who recently had lost a suit in that Court. Following passage of this resolution, Governor William Burnett, who then served as the Chancellor and who in that capacity had signed the decree against Phillipse, dissolves the Assembly. The next year, in response to these events, the Governor’s Council undertakes to promote reforms of many of the Chancery Court’s abuses — reforms that are adopted.

1731

Assembly Enacts Montgomerie Charter For New York City

The Assembly enacts the Montgomerie Charter for New York City. Under this charter, several changes are made in the City’s court structures. They include:

- Addition of authority for local Justices of the Peace to exercise jurisdiction over felonies at large, and

- designation of the Mayor, Deputy Mayor, Recorder, and Aldermen as ex officio Justices of the Peace.

This basic structure will define municipal administration for over a century.[57]

[57] Ellis, David M., et al, A Short History of New York State, p. 46.

1735

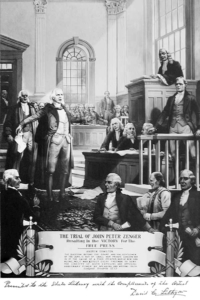

Seditious Libel Trial of John Peter Zenger Held in New York City

The trial of John Peter Zenger is held in New York City. Zenger is a printer who publishes a weekly journal that harshly criticizes New York’s incumbent governor, William Cosby. While Zenger does not actually write the offending material — it is the work of others — he is charged by the authorities with seditious libel. At first, it appears to be an open and shut case, the truth of the offending material being irrelevant under prevailing law (i.e., English common law, which seeks to punish not just false accusations against the government but simply any accusation against the government that is intended to hold it in “hatred or contempt” or to promote discontent or hostility among British subjects or to incite efforts to change Church or state law other than by lawful means). Zenger’s lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, however, convinces the jury that the dispositive issue should be whether, in fact, the allegedly libelous material is true. Thereupon, Zenger is promptly acquitted and several of the cornerstone principles of American law — freedoms of speech and of the press — are thereby inspired.

The trial of John Peter Zenger is held in New York City. Zenger is a printer who publishes a weekly journal that harshly criticizes New York’s incumbent governor, William Cosby. While Zenger does not actually write the offending material — it is the work of others — he is charged by the authorities with seditious libel. At first, it appears to be an open and shut case, the truth of the offending material being irrelevant under prevailing law (i.e., English common law, which seeks to punish not just false accusations against the government but simply any accusation against the government that is intended to hold it in “hatred or contempt” or to promote discontent or hostility among British subjects or to incite efforts to change Church or state law other than by lawful means). Zenger’s lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, however, convinces the jury that the dispositive issue should be whether, in fact, the allegedly libelous material is true. Thereupon, Zenger is promptly acquitted and several of the cornerstone principles of American law — freedoms of speech and of the press — are thereby inspired.

1737

Jurisdiction of Justices of the Peace Expands

By a further statute enacted by the provincial Assembly, Justices of the Peace are given jurisdiction over actions involving damages of 40 shillings or less.

1741

Supreme Court Justice Daniel Horsmanden Charged with Revising New York’s Judicial Laws

A Supreme Court Justice, Daniel Horsmanden, is commissioned to prepare a revision of laws in force affecting the colonial system of justice. Also, by colonial statute, the Supreme Court is given nisi prius jurisdiction ex officio.

A Supreme Court Justice, Daniel Horsmanden, is commissioned to prepare a revision of laws in force affecting the colonial system of justice. Also, by colonial statute, the Supreme Court is given nisi prius jurisdiction ex officio.

The Horsemanden revision of the laws is never completed. Some blame this on the fact that Justice Horsmanden is quite old when he undertakes his commission; and it is suggested that later efforts to impose a mandatory retirement age for judges are prompted by his example.

The nisi prius system, which originated in England, had been established in the colony toward the end of the 17th century. It allows for the trial of a case in the venue where the parties and witnesses reside (and jurors can be drawn), while leaving jurisdiction over preliminary proceedings and final judgment in the hands of a New York City-situated Supreme Court. This system saves the expense and inconvenience in the trial of matters arising at a distance from the City while assuring that the more technically and, potentially, politically challenging initial and final proceedings in such matters remain subject to the oversight of judges who are better-trained and, coincidentally, apt to be more sensitive to the Crown’s concerns. Historical evidence suggests that, despite its early establishment, the nisi prius practice actually takes many years to evolve, with greater reliance upon it depending upon population growth in the counties outside New York City and greater use of the information procedure in prosecuting regional crime.

1761

Debate Over Commissions of Supreme Court Justices Ensues

In the early 1760s, there is a serious debate in New York on the question whether its Supreme Court Justices should be appointed by the Royal Governor to serve at his pleasure or to serve during good behavior (as is then the case with English judges).[58] In the wake of this debate, the provincial legislature enacts a statute providing that Justices should hold their commissions during good behavior. Governor Colden refuses to assent, however. The incumbent Justices then petition the Governor in Council to renew their commissions during good behavior. The Governor postpones consideration of their petition pending instruction from England. The Justices threaten not to act unless their wishes are granted. The issue of tenure then becomes linked to judicial salaries. Ultimately, several Justices agreed to accept commissions for service at the Governor’s pleasure.

[58] Ellis, David M., et al, A Short History of New York State, pp 45-46.

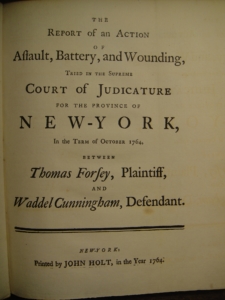

1764

Forsey v. Cunningham Decision Upholds Right to Trial by Jury

The case of Forsey v. Cunningham — a civil suit for assault in the Supreme Court of Judicature — results in a jury verdict and judgment for the plaintiff. The losing defendant then attempts to overturn the judgment by bypassing a writ of error in the courts and appealing directly to the Acting Governor. The provincial council, however, rules that any appeal from a jury verdict must proceed through the courts. This ruling is seconded by the English Attorney General and Solicitor General. The decision in Forsey is regarded as pivotal in upholding the right to trial by jury and in establishing that, in New York, the law was not what the Governor or even the Assembly by statute commanded; rather it was what local people, either jurors or trial judges beholden to local constituencies, or in the case of Supreme Court justices, to the bar, declared the law to be.[59]

The case of Forsey v. Cunningham — a civil suit for assault in the Supreme Court of Judicature — results in a jury verdict and judgment for the plaintiff. The losing defendant then attempts to overturn the judgment by bypassing a writ of error in the courts and appealing directly to the Acting Governor. The provincial council, however, rules that any appeal from a jury verdict must proceed through the courts. This ruling is seconded by the English Attorney General and Solicitor General. The decision in Forsey is regarded as pivotal in upholding the right to trial by jury and in establishing that, in New York, the law was not what the Governor or even the Assembly by statute commanded; rather it was what local people, either jurors or trial judges beholden to local constituencies, or in the case of Supreme Court justices, to the bar, declared the law to be.[59]

[59] Nelson, William E., Legal Turmoil in a Factious Colony: New York, 1664-1776, 38 Hofstra Law Rev., pp 37-39.

1772

Somerset v. Stewart Ends Slavery in England

Lord Mansfield writes the decision in Somerset v. Stewart, a case understood by many to have ended slavery in England. Somerset holds that, in order for there to be slavery in England, it must be authorized by positive law. At the time of the decision, slavery had never been authorized by statute within England and Wales; nor supported in England by the common law.

1776

American Revolution Creates Disarray in New York’s Courts

With the coming of the Revolution, the provincial courts fall into disorder. Many are presided over by loyalists to the Crown; and the American patriots often openly ignore or oppose their efforts to execute the duties of office. In September, as the British take New York City, the British commander, General William Howe, shuts down civil courts in the City and elsewhere within the British lines.

1776

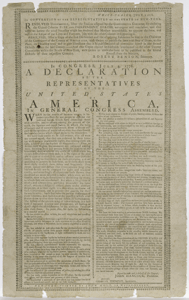

New York’s First Constitutional Convention Opens & New York Ratifies the Declaration of Independence

In response to urging by the Continental Congress that, in the wake of independence, each colony establish its own form of government, New York’s first Constitutional Convention opens in New York City.

In response to urging by the Continental Congress that, in the wake of independence, each colony establish its own form of government, New York’s first Constitutional Convention opens in New York City.

On June 30, 1776, anticipating an attack by the British, New York’s fourth provincial congress adjourns to White Plains, where, in the courthouse on July 9, it ratifies the recently issued Declaration of Independence. This congress includes 104 delegates from the State’s 14 counties and sits as the State’s first Constitutional Convention (called the “Council of Representatives”). Its task is to produce a State Constitution for the new state of New York.

1777

New York Adopts Its First Constitution

New York’s first Constitution is adopted in Kingston, to be effective April 20, 1777. It is written under the most trying circumstances, i.e., while working on the Constitution, the members of the Convention must scramble up the Hudson River (from White Plains to Harlem, then to King’s Bridge, Philipse Manor, Fishkill, Poughkeepsie, and Kingston) to elude the invading British army. Given these circumstances, it is not possible for the people of the new state to vote on their new constitution — so the Convention merely calls it into being.

New York’s first Constitution is adopted in Kingston, to be effective April 20, 1777. It is written under the most trying circumstances, i.e., while working on the Constitution, the members of the Convention must scramble up the Hudson River (from White Plains to Harlem, then to King’s Bridge, Philipse Manor, Fishkill, Poughkeepsie, and Kingston) to elude the invading British army. Given these circumstances, it is not possible for the people of the new state to vote on their new constitution — so the Convention merely calls it into being.

The new Constitution, which is primarily the work of John Jay, George Clinton, Alexander Hamilton, Robert Livingston, and Gouverneur Morris, includes no separate article devoted to the Judiciary, and just a few provisions regulating the courts — in effect carrying over the provincial judicial system, which, at the time the Constitution is adopted, consists of a Court of Chancery, a Supreme Court, a Court of Common Pleas, and Justice Courts.[60] The few provisions of the new Constitution that affect the courts address:

- Judicial selection, providing that all the primary judicial officers (i.e., Supreme Court Justices, the Chancellor, and certain County Judges) shall be selected by a Council of Appointment (made up of the Governor and four Senators selected by the Assembly).

- Terms of judicial office and mandatory retirement, providing that judges will hold office during good behavior subject to mandatory retirement at age 60.

- Impeachment and the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and the Correction of Errors, establishing a single forum to (1) act as an impeachment court, and (2) serve as New York’s appellate forum of last resort.

In serving as an impeachment court, this Court will consist of the President of the Senate (i.e., the Lieutenant Governor) as presiding officer, all State Senators, the Chancellor, and the Supreme Court Justices (or a major part of them). Impeachment and conviction by this Court will be the sole means by which an errant judge may be removed from office.

In serving as an appellate court, the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and the Correction of Errors is modeled after the English House of Lords. While the Chancellor and the Supreme Court Justices are to be active members of the Court, the constitutional framers carefully exclude them from playing any role in the decision of appeals before the Court where those appeals are from their decisions (although the constitutional text makes plain that, even under those circumstances, the Justices may participate in the deliberative process — at least to the extent of explaining the reasons for their judgments). - Council of Revision, providing that the Governor, Chancellor, and Supreme Court Justices shall sit together as a Council of Revision to determine the constitutionality of legislative enactments before they can become law. Each bill that passes the Senate and Assembly must be presented to this Council for its approval; and should the Council find the bill objectionable, it may return the bill to the Legislature within ten days in which event it will not become law unless it is re-passed by the Legislature with a two-thirds supermajority vote. With this Council of Revision in place, there is little reason for the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and the Correction of Errors to sit to determine the constitutionality of laws. Indeed, between 1777 and 1847, the Court declares only three statutes unconstitutional. Another reason that the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and the Correction of Errors declares so few statutes unconstitutional lies in the obvious fact that the Court is dominated by members of the Senate who likely would be disinclined to overturn statutes that they themselves already had approved.[61]

- Judges holding other offices, barring Supreme Court Justices and the Chancellor from holding other offices except that of delegate to the General Congress; and, likewise, certain County Judges from holding other offices except those of Senator and delegate to the General Congress.

- Continuation of the common law and colonial legislative enactments in effect on April 19, 1775 (the date on which the battle of Concord was fought), and the acts of the subsequent colonial and state legislatures in force on April 10, 1777 (ten days before adoption of New York’s Constitution), not inconsistent with the new Constitution. By expressly adopting the common law of England, however, the Constitution incorporates the English Bill of Rights of 1689 into the law of New York.

- Bar admission, providing for court regulation and supervision of the admission of attorneys to the Bar.

In fact, no rules regulating bar admission are actually adopted by the courts until 1797, when Supreme Court adopts a rule requiring that, to be admitted to the bar, one must serve a regular clerkship of seven years’ duration with a practicing attorney of the court to which a person seeks admission (although four years of classical studies undertaken after a person attains age 14 could be substituted). No examination is needed for admission.

The State’s first Constitution contains no Bill of Rights. Only the right to trial by jury is guaranteed.

[60] Article XXXV of the 1777 Constitution provides, in relevant part: “That such parts of the common law of England, and of the statute law of England and Great Britain, and of the acts of the legislature of the colony of New York, as together did form the law of the said colony on the nineteenth day of April in the year of our Lord, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five, shall be and continue the law of this state, subject to such alterations and provisions as the legislature of this state shall, from time to time, make concerning the same . . .” (emphasis added)

Inasmuch as the 1777 Constitution included no provision specifically addressing court structure (e.g., nothing enabling a Supreme Court), it may be concluded that its framers intended that the Supreme Court of Judicature, which had been created in 1691 by an early act of New York’s colonial legislature, simply be continued as part of the law of the new State.

[61] Lincoln, Charles Z., Constitutional History of New York, Vol. 1, p. 162.

1777

John Jay Becomes New York State’s First Chief Justice

1777

Robert Livingston Becomes New York State’s First Chancellor

1779

Richard Morris Becomes Chief Justice

1784

Legislature Regulates Court for the Correction of Errors

1787

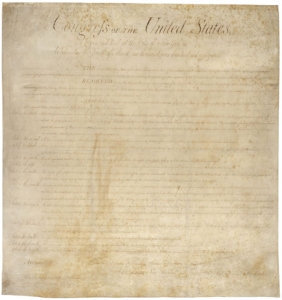

Bill of Rights Enacted in New York

A Bill of Rights is enacted as a statute in New York. It includes a variety of protections including:

- Due process,

- Prohibition of excessive bail/fines and cruel or unusual punishment,

- Free elections, and

- Freedom of speech and debate in the Legislature.

No formal Bill of Rights had been included in the State Constitution adopted in 1777 although there were several clauses guaranteeing basic rights including male suffrage based on residency, a right to counsel in both criminal and civil trials, freedom of religion, abolition of religious establishments, and the guarantee of due process.

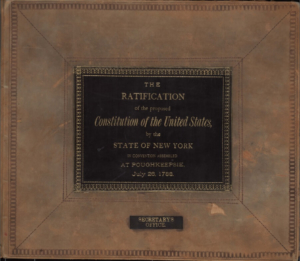

1788

New York Ratifies the U.S. Constitution

1790

Robert Yates Becomes Chief Justice

Robert Yates, an Associate Justice of the State Supreme Court from Albany, succeeds Richard Morris as Chief Justice.

1797

Albany Becomes Capital of New York State