By John F. Werner and Robert C. Meade Jr.[*]

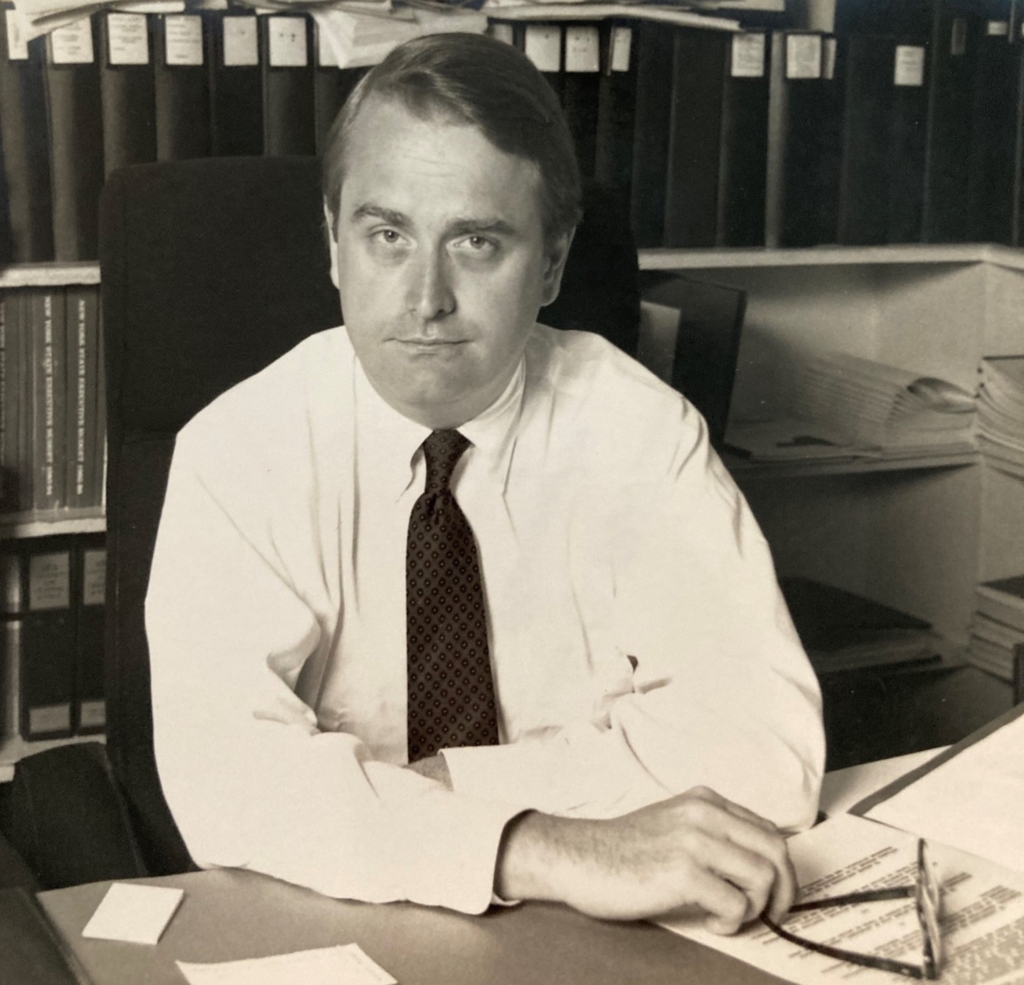

It has been 12 years since the untimely passing of Matthew T. Crosson, who served as Chief Administrator of the Unified Court System for four very busy and productive years and as Deputy Chief Administrator for several years before that. The skills, talents, leadership, and dedication Matt displayed made him an outstanding administrator. His contributions to the Court System and the public it serves were very substantial and thus we take this opportunity to remember him and reflect with gratitude upon his career and person.

It has been 12 years since the untimely passing of Matthew T. Crosson, who served as Chief Administrator of the Unified Court System for four very busy and productive years and as Deputy Chief Administrator for several years before that. The skills, talents, leadership, and dedication Matt displayed made him an outstanding administrator. His contributions to the Court System and the public it serves were very substantial and thus we take this opportunity to remember him and reflect with gratitude upon his career and person.

Matt Crosson was born in 1949 in Connecticut. He graduated from Georgetown University and took his Juris Doctor degree from Fordham University School of Law in 1974. Following in the footsteps of his father, he began his legal career as an Assistant District Attorney in the New York County District Attorney’s Office. He served there for almost a decade and was, among other things, Deputy Chief of the Frauds Bureau. In that role, he focused on the investigation and prosecution of banking fraud, embezzlement, securities fraud, and international arms trafficking. He is credited with having created a consortium of multistate law enforcement organizations specializing in white collar crime, which continues today under the name National White Collar Crime Center.

In 1983, Matt became Assistant Counsel to Governor Mario M. Cuomo, in which position he was responsible for legislation and other matters relating to the justice system of New York State.

Matt joined the state court system in 1985, when he was designated Deputy Chief Administrator for Management Support under then-Chief Administrator Joseph W. Bellacosa. Judge Bellacosa describes Matt in his role as Deputy Chief:

I recruited Matt and stole him away from Governor Mario M. Cuomo’s Counsel’s Office as my Mr. Inside, as I played Mr. Outside as Chief Administrative Judge in dealing with the many responsibilities and constituencies of managing the Judicial Branch of New York State’s vast and complicated system of government in the mid-1980s …. Matt was the perfect side-kick in my years, with his prodigious range of talents that proved themselves: brilliant creative mind and manager, diligent workhorse, and an always ready-at-hand gift for unearthing research, empirical backup, and evidentiary support to persuade and implement policies. He was first and foremost a classy perfectionist, personally and professionally, smoothed over by a dry and wry sense of quick humor to break tensions — the coolest, steadiest cat to have beside one through crisis management eruptions, as well as the daily day-to-day performance of duties. Through it all and above all, Matt was a dear, trusted friend ….[1]

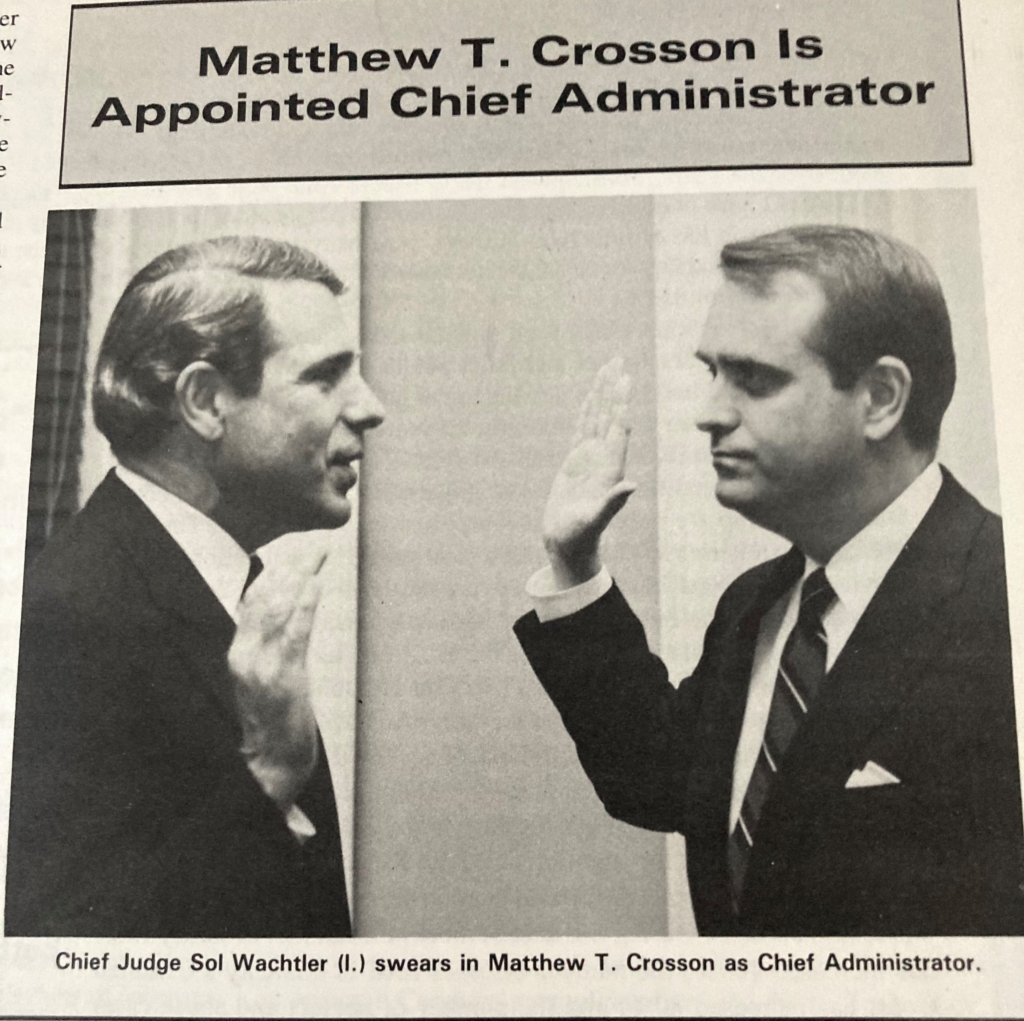

In his roles as Deputy Chief Administrator and later Chief Administrator, Matt worked closely with Chief Judge Sol Wachtler, who provided energetic leadership for the Court System on many fronts in those years. Judge Wachtler met Matt after the former was appointed Chief Judge. “Matt was one of the most intelligent persons I had ever met,” Judge Wachtler writes, “and what began as a professional relationship matured into a deep friendship.” In his view, “[a]lthough I was credited with significant administrative accomplishments during my tenure as Chief Judge,” the accomplishments achieved during the years when Judge Bellacosa and Matt Crosson were Chief Administrator “were all due to the creative and dedicated administrative abilities of Joe Bellacosa and … Matt Crosson.” He adds:

Joe Bellacosa, my dear friend and my first Chief Administrative Judge, did a remarkable and tireless job of meeting with jurists and non-judicial personnel in assessing … needs and lobbying the legislature to accomplish positive objectives. But perhaps Joe’s greatest accomplishment was luring Matt Crosson away from Governor Mario Cuomo’s counsel’s office — something for which Mario never forgave either me or Joe.

In those years, the New York State Court System faced many challenges. Judge Wachtler recalls:

When I was appointed Chief Judge, I was the beneficiary of an excellent administrative team which had been put in place by my predecessor, Chief Judge Lawrence Cooke; however, I thought it important to appoint a new Chief Administrator with whom I had a close personal and working relationship [that would be Judge Bellacosa]. Because of the increase in caseloads [and other factors], it was necessary to improve the jurisdiction and functioning of the courts in general and the New York Court of Appeals in particular. I thought there was a need to create an individual assignment calendar system … and that there was an acute need to garner additional funding to increase the number of judges and non-judicial personnel necessary to meet the heavy demands on the court system occasioned by the crack epidemic. I also thought it was imperative to increase judicial salaries and the compensation of our highly professional non-judicial personnel.

Among other things during his tenure as Deputy Chief Administrator, Matt served as chairman of the Court Facilities Capital Review Board, which oversaw the design, financing, and construction of courthouses in New York State. He conceived and wrote the legislation that became the Court Facilities Act of 1987, which led to significant increases in court construction. Judge Wachtler describes Matt’s work on this critical subject as follows:

It was Matt who said that “justice degraded is justice denied” when he set himself to the task of repairing our broken courthouse infrastructure. When the Unified Court System was created, the state took over the payment of salaries and benefits for the judicial and non-judicial personnel. However, the providing and maintaining of courthouses remained the responsibility of the municipalities. As time went by, New York’s courthouses became rundown and inadequate. This was not only a downstate problem; outdated and inadequate courthouses upstate were also falling apart. [2]

After an assessment of needs, Matt came up with the idea of compelling every municipality to submit a plan for renovating, rebuilding, or creating new courthouse facilities. According to his concept, after plans were approved by OCA, the municipality would be obliged to execute on those plans. If a municipality failed to comply, state aid to that municipality would be suspended. I thought Matt’s idea was brilliant, but I never believed it would pass the Legislature and then be signed into law. I was wrong. Today, almost every courthouse in New York State has been built, rebuilt, or overhauled because of Matt’s foresight, wisdom, and, most important, his ability to navigate the corridors of the state Legislature.

Judge Bellacosa was quoted as saying of Matt that “his singular responsibility and leadership for the courts’ facilities legislation stands out for me because it encapsulates so many of his gifts and skills. He shepherded that through to ultimate success with ingenuity, perseverance, and a doggedness which just plain wore out those who carried water for opposed special interests.”[3]

In 1989, Matt became the Chief Administrator of the Unified Court System. His extensive familiarity with the courts and his four years of experience in the administration of the Court System provided a solid foundation for his work in his new position.

Judge Wachtler recalls the difficulties that the Court System faced on the criminal side during Matt’s time in administrative leadership:

During the mid-eighties New York witnessed the AIDs epidemic, skyrocketing crime rates, and mass incarceration necessitated by the Rockefeller drug laws. The courts were so overwhelmed that Civil parts had to be closed down so that judges and other personnel could handle the exploding criminal court dockets. Rikers was so overcrowded with prisoners, who were not “state ready,” that floating prison barges, which the British had used as troop ships in the Falkland Islands, had to be floated off the shore of Hunts Point in the Bronx. Matt Crosson, with wisdom and ingenuity, guided the Court System through that maelstrom. Matt, with the assistance of other excellent OCA administrators, saw to it that the courts, and extraordinarily hard-working judges and non-judicial personnel, kept New York City from having to release prisoners, as was happening in many other cities.

On the civil side, the most important innovation under Judge Wachtler’s leadership was the introduction of the Individual Assignment System (“IAS”) and the championing of civil case management. Judge Wachtler created IAS, in his words, “to expedite the handling of cases and eliminate judge shopping ….”

It is hard to overstate the practical significance of the introduction of IAS for the civil side of the Court System. It is worth expending a few words to make clear why this was so. Prior to the introduction of IAS, the courts in New York had long operated with a master calendar system. Cases did not even come to the court’s attention until a motion or other application was made; the attorneys on the case would manage pre-trial proceedings themselves unless and until they reached a disagreement about a matter that required judicial action or until a judicial ruling was required on a question of law. When the cases did reach the court, they were not assigned to judges of the court. Instead, motions and ex parte applications, and trial-ready cases too, were placed on centralized calendars. Motions and other applications were assigned to Special Term Parts and judges rotated through those Parts.

Despite its historical pedigree, this mechanism for the allocation of judicial business was open to the criticism that it was highly inefficient. A judge (other than one in a one-judge venue or, to a lesser degree, judges in counties with small inventories) typically did not acquire familiarity with all or many of the issues in any given case and any particular case would almost inevitably be handled by more than one judge over its lifetime. If ten motions were made in a case, they might be handled by as many as ten different judges. The system wasted the knowledge about the facts and legal issues that a judge would gain in the course of handling a motion. When cases were ready for trial, they would be placed on a centralized trial calendar from which they would be distributed without regard to whether the judge to whom the case was assigned for trial had had previous involvement with the case or not.

Under a pure IAS system, cases would be assigned to judges for all purposes through a random assignment process. All applications would go before one judge and that judge would also try the case. Knowledge of the case would be accumulated by the assigned judge over time, not wasted through the involvement of multiple judges; attorneys would not have to re-educate multiple judges about the issues involved; and consistency in the rulings issued was assured to the maximum extent possible.

The IAS system also allowed for the possibility of active supervision of the pre-trial disclosure process by the assigned judge. Such involvement could lead to greater efficiency in discovery, the avoidance of disclosure motions, the minimization of costs for the parties, and more expedited proceedings.

The theoretical benefits of IAS were plain to anyone who considered the matter with an open mind. The question was — an important question that arises in many forms under many circumstances in many a bureaucracy — whether the theoretical benefits could be realized in the real world, particularly in courts with large inventories. By the time the introduction of IAS was being considered, the Court System and its entire staff working on civil cases had long since become habituated to the master calendar system and looked upon that system as the natural way of doing things. Knowledge about the new system would have to be acquired by all judges and staff over time before it could be expected that IAS would be implemented with maximum possible efficiency. Further, in the courts, as in other bureaucracies, any new initiative will often be opposed by some segment of the staff simply because it is unfamiliar and that opposition will be an obstacle to the smooth and expeditious implementation of the new idea. The challenges facing Matt Crosson as Deputy Chief Administrator and Chief Administrator were to identify the technical means needed to handle the work under the new system and so bring the Chief Judge’s vision to life and find ways to empower and encourage the staff to make the journey.

The technical challenges were formidable. Under the master calendar system, the staff placed all motions filed in the court on the calendar of Special Term, Part I and delivered the papers on the motions to that Part, and would have to track the weekly or bi-weekly assignments of judges flowing through that Part. With the advent of IAS, however, each judge would have his or her own Part and the staff would need to create motion calendars for every Part every week. Each Part, of which in the largest courts there could be as many as 50 or so, would have a motion day and attorneys would have to make motions returnable in the correct Part and for the correct motion day, whereas under the master calendar system, a motion need only have been made returnable in Special Term, Part I on any business day. The motions returnable on the motion day of each Part would have to be calendared for that day in that Part and the papers for all of those motions would have to be delivered to the Part, and delivered on time. Thorough and accurate records would have to be kept as to the status of each motion. Adjournments, the recording of which was centralized under the master calendar system, would have to be accurately processed in each Part for every motion day. After decisions were rendered, the decisions and the motion papers for the motions in question would have to be collected from each Part or from the Chambers of each judge and transmitted to the clerk’s office for processing. Notations would have to be made in the court’s records for every motion once decided to the effect that a decision had been issued so that the motion no longer would appear as “open” in the court’s records. In short, under the new system, there necessarily was a considerable amount of theretofore unknown administrative activity and movement of papers around the courthouse.

To keep track of the history of activity in each case, the Court System created a mainframe computer application known as the “Civil Case Information System” (“CCIS”). This application was put into place in the 13 largest counties in the state in 1986. Local computer applications were used elsewhere. Matt as Deputy Chief Administrator for Management Support was in a critical position as CCIS was created and rolled out and as other applications were developed in other venues. He provided vital leadership in this time of challenge for the Court System. He also had a large role to play in effectuating the operational adjustments made by the clerks of each court as they ceased to work with the centralized calendars and implemented individualized ones for every Part. This transition continued for several years during Matt’s time as the Chief Administrator.

Throughout the transition from master calendars to IAS, Matt worked very closely with court personnel, and especially with the then-Chief Clerk of the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County, Jonathan Lippman, Esq., and with the Unified Court System’s then-Counsel, Michael Colodner, Esq. Messrs. Lippman and Colodner, reporting to Matt, immersed themselves in drafting of new Uniform Rules necessary to effectuate the transition to IAS. Chief Clerk Lippman was very much on the frontlines when it came to the operational changes necessary to effectuate IAS in New York City and beyond. Later, in 1989, Matt recruited Chief Clerk Lippman to serve as Deputy Chief Administrator for Management Support.[4]

This transition was a mammoth one: the implementation of the IAS system was surely the greatest operational change on the civil side that the clerks of that time across the state had ever seen in their careers and that the courts as organizations had encountered, at least for decades. The arrival of CCIS and other computer applications alone ushered in a whole new world for all of the clerks in the Court System on the civil side. Every clerk had to learn how to work with an entirely new piece of equipment — a computer — and a medium that was theretofore unknown and must surely have seemed strange and perhaps even bewildering to many a clerk, records having been kept by hand prior thereto. Each clerk had to achieve a level of mastery with the relevant application so as to be able to work with it efficiently and effectively on a daily basis. Even all of the Chambers had to gain some understanding of how CCIS and the other applications worked, the information they provided, and the limits on their capabilities.

Inevitably, there were difficulties that had to be overcome, including, as alluded to, the need to persuade some judges, court staff and members of the trial bar of the efficacy of IAS. Adjustments had to be made to CCIS and the other applications as the courts gained experience with them and the operations of the IAS system. It took some years before things ran smoothly. But, looking back today on this great undertaking, we think it is clear that the transition was effectuated just about as successfully as could reasonably have been expected of an organization as vast as the New York State Court System. Nothing vital to this effort was overlooked and the direction and training made available proved to be highly efficacious. Matt was at the center of this vast effort and it could not have happened without him. He provided the leadership under which the administration and staff of the courts, including his loyal management team and the Administrative Judges in Judicial Districts across the entire State, brought into being the vision of the Chief Judge.

In time, the introduction of IAS led the courts to address the large and important task of individualized case management in civil cases, a matter on which the courts of New York, and indeed courts all around the country in both state and federal systems, continue to labor energetically today. Steps taken in the area of case management include the development of “standards and goals.”

In the private sector, a business can understand and measure its success or lack thereof and take appropriate action in response by generating and keeping a close watch on key points of data, about the number of products produced, the number of employees, profitability, and the productivity of the employees. When, however, the purpose of an organization — the court — is the elusive one of providing justice, it is more difficult for that organization to take stock of successes and failures and to make necessary changes and improvements. But it is nevertheless important for the courts to track their work insofar as practicable and to be guided by what the data reveal.

One goal of the system of justice, of course, is to provide justice in a timely manner. Standards and goals, however generic, offered some means for judging how well or ill the courts were doing in achieving this objective. These measures served both to promote understanding of the productivity of the courts and to spur innovations and greater efficiency. Standards and goals in civil cases began with a standard for the completion of judicial proceedings in the post-note-of-issue phase of the litigation (15 months from filing of the note of issue). Over the years, the measures expanded to the pre-note-of-issue phase as the courts sought to make progress managing cases from their early days to disposition. Standards were also created for criminal cases. Matt was able to report that, in 1991, 84 % of the felony dispositions statewide were achieved within the standard and goal, which was six months from filing of the indictment, and 79% of note-of-issue dispositions in civil cases were brought about within the 15-month standard.[5]

In regard to case management and standards and goals, too, Matt faced obstacles that needed to be overcome inasmuch as more than a few judges, staff members and attorneys, being accustomed to case management in the hands of the lawyers, were resistant to change. A major task shouldered by him, then, was to persuade the hesitant of the importance of the new direction to achievement of the goals of the courts and to the provision of a better quality of justice for all the citizens of New York State. The goal was to bring everyone on board in pursuit of this great common objective.[6]

When Matt became the Deputy Chief Administrator, the courts of the state carried on business using rotary telephones, and decisions, orders, and other documents were created on typewriters. Matt led the Court System to adopt digital technology and integrate it into the conduct of judicial business. This was the beginning of a vast sea-change for New York’s courts. In 1986, as indicated, record-keeping in the Court System began to be supported by a mainframe computer system and various local applications, but there were no personal computers in use. Later, computers were made available on a limited basis. Decisions, orders, and other documents began to be created using word processing software. Applications were provided to the courts to enable judges and court attorneys to cite-check cases and perform other tasks digitally. The authors vividly recall when a computer was placed in the library of the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County at the New York County Courthouse to enable attorneys of the court to cite-check cases. As one might expect given the difficulty and drudgery of cite-checking using the red-bound hardcover Shepard’s citators (often, to cite-check a single case one had to consult a main volume, multiple supplements, and paper-bound updates), the arrival of the computer created a great stir and it was in very high demand. No one at the court realized it then (though Matt no doubt did), but that computer was a trojan horse; digital technology in time was to render the traditional law library, including the venerable library in which that machine was located, a relic of the past.

The path that Matt charted led to even greater changes and improvements in productivity in the years afterward. In time, personal computers displaced typewriters, e-mail became ubiquitous, the conduct of legal research on-line became routine and was effectuated by judges and court lawyers on individual personal computers and tablets, including remotely at night and on the weekends, and the courts made information known to the bar and the public through websites and other electronic means. Eventually, these steps led, in 1999, to the establishment by the Court System of a program for the electronic filing and service of litigation documents. This program has dramatically altered the way in which litigation is conducted in New York, the operations of the courts, and the functioning of the offices of the County Clerks across the entire state. Just as digital technology made obsolete typewriters, Shepard’s, and hard-copy case reporters, e-filing has rendered the record rooms of the County Clerks statewide largely superfluous. E-filing has greatly increased efficiency and productivity for the courts, the County Clerks, and the bar. It was Matt who, to a significant degree, first pointed the Court System to the digital pathway it was to follow and still follows today.

Matt was required to keep the Court System on an even keel during a tumultuous time in 1991. Faced with a fiscal crisis, the Governor purported to cut 10 percent from the budget of the Judiciary. This led to a dispute between the Chief Judge and the Governor. In Judge Wachtler’s recollection, “while the Governor and the legislature were increasing the budget of the Department of Corrections, they were decreasing our very lean budget by the same percentage.” Unfair criticism of the courts during the surge in crime contributed to the reduction in the budget. “A consequence of this kind of rhetoric,” Judge Wachtler writes, “was that it made it easy for the Governor and State legislators to deny Matt, and the Office of Court Administration, desperately needed resources.”[7] The Chief Judge contended that the Governor was obliged under the Constitution simply to forward the budget of the Judiciary, an independent and equal branch of government, to the Legislature without revision, though with whatever recommendations he deemed appropriate.[8]

There were some 700 vacancies in May 1991 when a hiring freeze was imposed.[9] Later that year, layoffs were initiated in the civil courts because of the shortage of funds.[10] In some courts, this led to the closing of Parts, reduction in the number of trials held, delays in the disposition of motions, and the like.[11] In New York City, almost one-third of the civil courtrooms in Supreme Court were closed and small-claims sessions were reduced from four nights a week to one.[12] Litigation ensued over the issue of the Governor’s authority under the Constitution to cut the Judiciary budget.[5] The dispute was finally resolved by an agreement in January 1992.[13]

Matt was required to keep the courts functioning to the maximum extent possible under the very trying circumstances of the budgetary shortfall. This he did with the patience and calm that were customary to him. By March 1992, Matt was looking forward to a restoration within months of employees lost in 1991-92 and to re-establishment of lost court services.[14]

It was under the leadership of Chief Judge Wachtler and Matt that the Court System in 1992 began to enhance the processing of commercial cases. New York State was and had long been the commercial capital of the United States and it was important, therefore, that New York’s court system facilitate the conduct of commercial litigation with as much efficiency as possible and that the New York courts keep pace with the ever-growing sophistication of the commercial world out of which the cases emerged. With the goal of modernizing and improving the way in which these difficult cases were handled, extensive planning was undertaken in 1992 to develop a pilot project for commercial cases in which concentrated and specialized judicial attention would be brought to bear on the cases. The plan was to establish, in January 1993, four Commercial Parts in the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County, where many of the world’s great commercial enterprises are headquartered or have major offices and where much commercial litigation has long been brought. Commercial cases were concentrated in these Parts and highly-experienced, veteran Justices, designated by Matt with input from the Honorable Stanley S. Ostrau, the Administrative Judge of the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County, were assigned to the Parts (i.e., Justices Myriam Altman, Herman Cahn, Ira Gammerman, and Beatrice Shainswit). The Parts, which commenced operations in January 1993 as planned, enabled the Court System to devote to these complex cases judicial expertise in commercial law and skill in the administration of the inventories, particularly with regard to supervision of disclosure, which in commercial litigation can easily become protracted and inordinately costly absent skilled, energetic, and effective judicial oversight.

The Commercial Parts proved to be a very great success. The commercial bar was most enthusiastic about the Parts, the quality of their work, the knowledge of commercial law and familiarity with discovery problems in the commercial context displayed by the Justices, the productivity of the Parts, and the expedition with which the cases were handled. At the same time, the removal of these complicated matters from the inventories of the general Parts allowed those Parts to improve their handling of the non-commercial cases in the inventory. The success of the Commercial Parts was so great that, in 1995, they matured into the Commercial Division, in time expanding into other venues around the state. The Division has been and remains to this day a very successful part of the administration of civil justice in New York State.

Indeed, the Commercial Parts became a model for many other states in this country and even around the world, from many areas of which visitors came to New York County in particular to examine the operations of the Parts and later the Division. A study of the development of commercial courts in the decade or so after the establishment of the Commercial Parts in New York concluded that the Commercial Parts pilot program was “a critical point of origin for the decade long trend in creating business and commercial courts.”[16] The authors also found that “New York’s efforts … had a powerful impact in other jurisdictions.”[17]

Matt did not devote his energies only to the inventory of the largest and most complicated cases. In 1990, the Court System established a Town and Village Courts Resource Center to provide information, advice, and legal research to these important courts. This was the first time that the Court System made such resources available to these courts.[18]

Matt was very sensitive to the vital imperative that the Court System of New York ensure the equal application of the law to all citizens in the courts and fair and equal treatment of all in the operations of the Court System, including staff members of the courts and those interested in becoming staff members. For example, in the early 1980’s, then-Chief Judge Lawrence Cooke appointed a Task Force on Women in the Courts. Following the issuance of the Task Force’s report in 1986, a Judicial Committee on Women in the Courts was established by Chief Judge Wachtler, the Hon. Kay McDonald, Chair, succeeded by the Hon. Betty Weinberg Ellerin. Matt was very supportive of the important work of the Committee. Matt understood well the challenges facing women lawyers and the need to expand opportunities for women in the law, both in the courts and in the profession generally, an understanding no doubt made deeper and more concrete for him by the fact that his wife, Elaine, is herself an attorney. These efforts by the Committee, which remains active today, and by the Court System generally contributed to a notable increase in the number of women judges in New York and of women within the ranks of the Court System in the years since the Committee’s creation.

In 1988, Chief Judge Wachtler established the New York State Judicial Commission on Minorities and appointed Franklin H. Williams as its chair. Mr. Williams was a distinguished attorney and civil rights leader, who, among other things, had served as a high-ranking Peace Corps official and a United States Ambassador. The Chief Judge charged Ambassador Williams with the responsibility for conducting research on the treatment of minorities in the court system. The Commission issued a thorough report, beginning with an interim report in May 1990. The work of the Commission proved to be highly persuasive and influential. The Commission was established as a permanent entity within the Court System and renamed the Franklin H. Williams Judicial Commission on Minorities and it remains active today.[19] Matt was deeply involved in the establishment of the Commission, assisted in its work, and led the implementation of its recommendations for improvements to the operations of the Court System in this area. Much progress has been made since 1988 and more progress will no doubt be made in the years ahead building upon the foundation that was created then.

Within the structure of the Central Administration, Matt was similarly supportive of the then-Office of Equal Opportunity (Adrienne A. White, Esq., Department Head) (now the Office of Diversity and Inclusion). Matt understood and promoted throughout the Court System the principle that our courts need to be committed to equality and fairness, gender, racial, and religious, for all people and that the staffing and operations of the Court System must reflect this commitment. By 1992 a Workforce Diversity Program was in operation that aimed to expand opportunities for women and minorities in all job categories within the Court System, and efforts along these lines have continued in the years since.[20]

Another area in which Matt was active was that of justice for children. In 1988, Chief Judge Wachtler established the Permanent Judicial Commission on Justice for Children. The Commission was aimed at developing a consensus among experts in the field of juvenile justice on ways to achieve comprehensive changes to the Family Court and the entire juvenile justice system.[21] As intended, the work of the Commission continues today.[22]

It was apparent in these and other major undertakings and in all of the daily work of the Court System that Matt was blessed with many gifts that together made him a superb administrator. He was, as Judge Wachtler noted, highly intelligent. He had a reputation, richly deserved, for being exceptionally well-organized. He had an astonishing capacity to absorb and retain information and organize it in his mind, including information about the operational details of our vast and complicated court system. He was not rigid or inflexible in his thinking, but rather was open-minded and learned from experience. He prioritized the work and the goals of the Court System, not the needs of ego. Although he knew a great deal about all the subjects with which he was called upon to deal, he did not mislead himself into believing that he always knew all that he needed to know and he was never afraid to call upon the staff of the courts to add to his bank of information. He also understood the complexity of such a large organization as the Court System. He realized that operational mechanisms that might work in Supreme, Criminal might not be suitable to the Family Court or the Surrogate’s Court, and that procedures employed in one part of the state might not be advisable elsewhere.

Further, a job such as that of Chief Administrator imposes innumerable challenges and the demands placed upon the Chief Administrator’s time are very significant. It is vital, therefore, that the Chief Administrator manage his or her time as effectively as possible, that he or she give priority to the most important matters and not become distracted by countless issues of secondary importance. A person can easily be overwhelmed by the burdens of the office, but Matt was always in command.

Matt was a close analyst of ideas. This came naturally to him, but was perhaps also influenced by his time as an Assistant District Attorney. He always made sure to examine ideas and proposals with great care, to study all aspects of a proposal, to look for benefits but also be aware of potential weaknesses, to challenge and test ideas, and to consider all possible implications and potential pitfalls before moving ahead. In this process, he was not only open to, but actively encouraged, the submission of ideas and suggestions from his staff and other administrators. He did this, of course, with his senior staff at the Office of Court Administration. But he also took great pains to consult with the staff members of the courts who were in a position to offer useful insights, make productive suggestions, or challenge ideas. He respected and consulted closely with, not just his senior staff, but also the District Administrative Judges of the courts and with the Chief Clerks around the state. He encouraged all of them to offer ideas and to make criticisms since he was keen enough to recognize that they had deeper understanding than anyone else of the operations of their different courts and the needs of the bar practicing in them and the litigants who came before those courts. What mattered to him was the identification of better ways of doing things, not where those ideas might originate.

Likewise, as appropriate, he was willing to delegate matters to senior administrators, Administrative Judges, and Chief Clerks because he was fully aware that he could not do everything himself — no one human being could. He was never a micro-manager and his sense of self was never so invested in his work that he felt a need to be seen to be at the front of every line. He believed that a thoughtful operational philosophy, one that emphasized collaboration, deliberation and cooperation, was the best route to an efficient and productive court system. He strove to build and sustain a team approach to the operations of the courts. Something Newsday wrote about Matt’s work on Long Island after he left the Court System applies very much to his work for the latter; he “discovered early on a very simple truth that eludes too many in positions of leadership. Nothing gets done without cooperation, and with it, anything is possible.”[23]

Judge Joseph J. Traficanti served as Deputy Chief Administrative Judge for the courts outside New York City when Matt was the Chief Administrator. The Judge describes Matt’s philosophy of leadership as follows:

I came to the DCAJ position with little experience in judicial administration on the state level and minimal experience on the district level. Luckily, Matt had those qualities and gently and patiently passed them on to me. He was a superb supervisor in many ways. He supported me and others by permitting us to “do our own thing” in that he encouraged new ideas and initiatives and evaluated fairly the pros and cons, realizing that one size did not fit all. E.g., what worked in New York City may not work in Albany and what worked in Albany did not necessarily work in Buffalo. His inclination was to support new and innovative ideas at the OCA, Deputy Chief Administrative Judge, and district levels. He invited, even encouraged, input through his open-door policy and always returned phone calls. He knew how important teamwork and collaboration were between and among OCA, the district administrative judges, executive assistants (so called in those days), the bar, and what he called “our partners in government.”

Matt sought to institutionalize this collaborative philosophy of administration. Both as an occasion to promote consultation and the exchange of ideas and as a concrete manifestation of his commitment to these goals, Matt conducted regular meetings with the district Administrative Judges. Judge Traficanti writes:

[Matt’s] openness [to collaboration] led to bringing the Administrative Judges from outside New York City together at two-day regular quarterly meetings with prepared and pre-distributed agenda covering the issues of the time, e.g., electronic recording, Standards and Goals (new and shocking to the Administrative Judges of the time), etc. At these meetings he supported special programs such as leadership formation, substance abuse programs, and automation initiatives as the Court System moved towards the age of technology. The real goal at the time was the transformation of the Administrative Judges into a collective advisory team, as well as enhancing the idea of judicial leadership on the district level. This was surprisingly innovative to the 12 Administrative Judges outside of New York City (including the Presiding Judge of the Court of Claims), who had been selected Administrative Judge because they were the senior Supreme Court Justice of the district. They all adapted to this system, albeit in varying degrees.

Despite his mastery of detail, Matt always made sure that he took time to focus attention on larger matters, on structural challenges, and on developing innovations that might bring about large-scale improvements in the workings of the courts. The administrator’s acuity in identifying large challenges and foresightedness are very important to the success of a vast organization like the Court System. An administrator, with the best of intentions, eager to stay on top of things, can become so absorbed by the to-do list and today’s schedule of meetings as to have little time to think about larger questions and about the future and its needs. Matt, however, was always prescient and visionary. We can see examples of this throughout his career in the Court System and before and afterward. For example, as we discussed, Matt saw the future when it came to technology at a time when few others did. He perceived very early the changes that were on the horizon as a result of the advance of technology and he recognized how those changes could bring benefits to the New York Courts, to litigants, and to the bar. After careful study, he urged that those changes be embraced. In the early 1990’s, he assembled court administrators at the New York City Bar Association for a demonstration, which he conducted personally, of how desk-top computers, local and wide-area networks, and e-mail could and would change our lives and impact fruitfully the workings of the courts. Characteristically, he sought to overcome the doubts of the resisters — and there were resisters — not by heavy-handed insistence on mandates and directions from on high, but by patience, calm, good humor, and, above all, by reason, which was one of the main pillars of Matt’s approach to his work. Matt’s vision about technology was, of course, correct. The importation of digital technology into the Court System changed it profoundly, bringing about a vast increase in productivity, an achievement that today we take for granted. As alluded to earlier, the path Matt put the Court System on back then continues to bring new benefits to the courts of New York today.

So extensive and diverse was the work that landed on Matt’s desk during his years in the Court System that it is not possible to do more here than, by way of the illustrations recorded here, touch upon some of the other matters for which he had responsibility and concerning which he provided devoted, energetic, and highly innovative leadership.

It is most important that the Court System respond to the needs of communities facing special problems in the administration of justice. One way to do that when circumstances make it appropriate is by the establishment of community courts. The Midtown Community Court in Manhattan, the nation’s first community court and a national model to this day, was established in 1992 when Chief Judge Wachtler, Mayor David Dinkins, and Matt conducted a ribbon-cutting ceremony before a large crowd on a busy street in midtown. This court focused attention on the adjudication of quality-of-life crimes and, as warranted, has sentenced offenders to community service rather than prison and has provided on-site social services. Judge Wachtler credits this initiative to Matt and Judge Robert G.M. Keating.[24] This innovation during Matt’s tenure was later expanded to other venues in New York City and the state.[25]

Another area in which Matt’s foresight and vision were displayed is that of alternative dispute resolution. Matt recognized that court-annexed ADR could assist the Court System to provide more expeditious and less costly resolution of some legal disputes than disposition by a determination by judge or jury, especially in comparatively simple cases in which modest sums were at stake. The Community Dispute Resolution Centers Program, now a unit of the Court System’s Statewide ADR Office, provides a statewide network of community forums for the resolution of disputes in lieu of litigation. In 1984, the Program, which was supervised by the Chief Administrator, was made a permanent component of the Unified Court System.[26] In that period, ADR was also made available in the New York City Civil Court.

Matt sought ways to expand further the possibilities of ADR in the Court System. By the early 1990’s, for instance, Administrative Judges and Chief Clerks were being encouraged to learn about ADR, including by attendance at seminars on the subject. When the Commercial Division emerged from the experiment with Commercial Parts, it established an influential mediation program. By 1996, an advisory committee was making recommendations to the Court System for the increased use of court-annexed ADR.

Matt was admired by those who worked with him for his fine personal qualities, including steadiness under pressure, evenness of temper, good humor, and personal rectitude. In all of Matt’s work on behalf of the Court System and the citizens of New York he displayed rock-solid intellectual honesty and a fierce devotion to, and demand for, the highest ethical standards.

Administrative responsibility can be daunting, unsettling, and draining. Administrative Judge Ostrau used to say that one of his privileges serving in that capacity was on innumerable occasions to make, at one and the same time, one person happy and everyone else angry. Matt coped well with the unceasing pressures of his position and the burdens of the workload it brought, never allowing them to distract him from his goal of moving the New York State courts ahead.

For Judge Wachtler,

Matt was a committed administrator who could be tough when he had to be, but who never lost his amazing sense of humor. He recognized his own fallibilities and had a keen sense of the human frailty in all of us. I never knew him to be partisan, unfair, or purposefully insensitive.

Matt’s Irish background perhaps had something to do with his dry sense of humor, although he did not make a great display of this background (with the exception that he always enjoyed marching with the Court System’s pipe band in the St. Patrick’s Day parade).

Animating everything Matt did was his deep understanding of the importance of the mission of the courts to the functioning of a free society. As Judge Traficanti, who later served as a consultant on the judiciary in a number of foreign countries, writes:

Many of Matt’s public statements, speeches, and private musings inevitably addressed his hard and fast commitment to the bedrock principles of our society — commitment to democracy and the rule of law. He continually emphasized these principles, having no way of knowing (nor did I) that I would be touting them in Eastern Europe and Central and Southeast Asia in their emerging democracies. Sure, I knew and believed it all in theory, but Matt had a way of making these principles come alive for audiences — whether they be judges, judicial employees, or a complainant who had just lost a lawsuit. I was fortunate to acquire from him some of those skills and was able to share them in my consultant work. I could mentally hear him discuss the importance of justice being independent, timely, fair, and transparent — the foundation of the trust and confidence which any public institution must have to remain relevant among the people it serves.

He said that a truly independent judiciary is the golden thread running through any society that can call itself civilized going back to the beginning of written history.

Matt was wise to see the alternative — justice administered on the streets through clans, families, gangs, paramilitaries. A trusted, independent judicial system is the vital alternative.

Judge Traficanti notes also that the independence of the judiciary was critical to Matt and that he understood that the judiciary had to be active in safeguarding its unique role.

Matt saw that the judiciary had to speak for itself and portray its successes on a regular basis. He accurately saw that the judiciary, to have the trust and confidence of the body politic, must protect itself. Our part, he opined, is to be accountable and transparent …. How fortunate I was to absorb this since I have taught it repeatedly in several countries, warning those in their judiciaries that it is up to them to protect “their” institution. If a void is allowed to exist there are those from the other branches or outside the branches who will be happy to fill it.

Judge Traficanti believes that Matt would be “distressed and anguished to see the contemporary attacks on the judicial branch and on other institutions supporting the separation of powers and checks and balances we have survived by so far.”

When Matt’s time as Chief Administrator came to an end, he could easily have found his way to a comfortable and highly-compensated post in a major law firm, but he chose instead to continue public service, in a new form. The choices of direction he made then and throughout his career say much about the kind of person he was. It is also revealing that after his departure, he continued to interest himself in the problems and successes of the Unified Court System, calling former colleagues from time to time to review developments. From these discussions colleagues realized that this was not simply a matter of natural curiosity about the fate and results of the countless programs and projects he had set in motion or promoted during his tenure as Chief Administrator and Deputy Chief Administrator. His interest went deeper than that: he remained devoted to promoting the rule of law and in the corner of all of those who sought to advance that great goal.

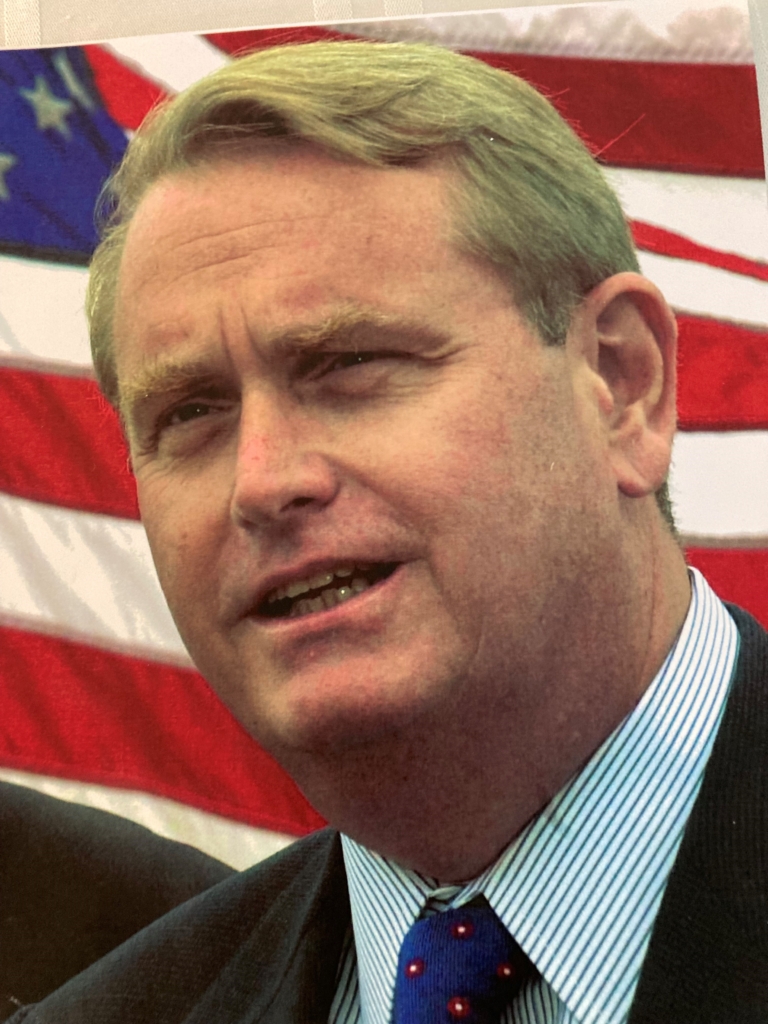

In 1993, Matt became the President of the Long Island Association. In that position, he became hugely influential. In the words of Suffolk County Executive Steve Levy, Matt “helped build the LIA into a powerhouse. When governors came to Long Island, they called the two county executives and Matt Crosson.”[27] Under his leadership, the Association grew in influence and stature and its membership increased by almost 75%.

As LIA President, Matt became a familiar figure to New Yorkers on Long Island and beyond from frequent appearances on television on a program for which he was the driving force. There, with the thoroughness and thoughtfulness that were characteristic of him, he focused attention on the problems of Long Island and New York State and sought to advance ideas for solving those problems, as well as issues of national interest. Matt’s program was a model of calm reflection and a sincere search for ways to improve life for everyone, an oasis of reason, especially compared to the ways in which public questions are too often addressed today. After his untimely passing, Newsday wrote of him in an editorial, entitled LI Owes Thanks to Matt Crosson, that he was

a man who was one of Long Island’s biggest and best advocates…. Though not a government official, he possessed the qualities we always say we want in our elected representatives. He was a leader, he had courage and he was a conciliator who brought all sides to the table.

As head of Long Island’s largest business group, [Matt] was a strong advocate for the business community. But more than that, he had a vision that addressed the quality of life for all Long Islanders. He wasn’t afraid to take on controversial issues, like building affordable housing and cutting the size of school district bureaucracies. [28]

Matt’s vision for Long Island and the downstate area continues to resonate today. Only the other day, an article appeared in Newsday that quoted Matt’s ideas for economic development on Long Island and noted progress that has been made recently in the implementation of those ideas in the context of the long effort to develop a life sciences industry on the island.[29]

In addition to his position at the LIA, Matt was a director or trustee of WNET, Inc., WLIW/21, the Long Island Housing Partnership and Dowling College, among other institutions.

In the spring of 2010, Matt assumed the position of President and Chief Executive Officer of the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce. Matt’s steady hand advancing and diversifying the business interests of the Las Vegas community would have been invaluable to all the citizens of that community, but, tragically, his contributions were cut short by his illness.

Matt was greatly blessed in his private life. Judge Bellacosa recalls that Matt

courted my first and outstanding law clerk at the Court of Appeals, Elaine Liccione, right under my unwary nose on his many visits in and out of my Chambers on official business. And when they finally decided to tell me of their courtship, they also asked me to officiate at their wedding — a most happy honor that began their beautiful, albeit shortened marriage, blessed and graced, however, by their wonderful son, Daniel.

In addition to Elaine and Daniel (as well as the students whose educations have been advanced by a scholarship established in Matt’s memory by the Crosson family), Matt left behind many friends and admirers in the Unified Court System and outside it. He left behind, too, a record of high service and great achievement, both in the Court System and in the wider community, the public benefits of “a brilliant career,” in Judge Bellacosa’s words. Matt left behind a model of what a public servant should be, a model that remains vital and relevant to this day, one that, were it followed generally, would make our country an immeasurably better, more just, and more humane place. Anyone would be proud to be able to boast of such a record, although a proclivity for boasting was not part of Matt’s makeup. There are many who remember and will continue to remember Matt’s work and the kind of person he was and who know that the Unified Court System and the system of justice in New York State today, as well as the larger community, are very much the better because of the imprint that Matt Crosson had upon them. May his memory continue to be a blessing.

[*] John F. Werner was the Chief Clerk and Executive Officer of the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County from 1989-2019. Robert C. Meade Jr. served as his deputy for many years. This article is a substantially expanded version of the article cited in Footnote No. 3. The authors express appreciation to the Judges who have contributed their recollections to this article and acknowledge with gratitude the assistance in the preparation of this piece provided by Michael F. McEneney, Esq., who had a distinguished career in the New York State Court System, and Allison M. Morey, Deputy Director, Historical Society of the New York Courts.

[1] Except as otherwise indicated, quotations in this article from Judges Bellacosa, Sol Wachtler, and Joseph J. Traficanti are from Messages of Oct. 17, 2022, Nov. 4, 2022, and Oct. 23, 2022, respectively.

[2] Judge Wachtler cites examples of courthouse conditions of the time: “A room in the clerk’s office of the Sutphin Boulevard courthouse in Queens was created in a walk-in safe. To access one of the judges’ Chambers in that same courthouse you had to walk up rickety stairs to gain access to the attic. The filthy and rundown courthouse in the Bronx … had to be completely rebuilt. In the Suffolk County Riverhead Courthouse, when a toilet was flushed upstairs, the lawyers trying a case in the basement had to stop talking.”

[3] Quoted in the authors’ article “Matt Crosson, Innovative Administrator Who Was Always Prepared” in Just Us, a publication of the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County (Spring 2011). Despite the clear success of Matt’s court facilities legislation over the course of several decades, not all courthouses in the state are today, 35 years after the Act, in pristine condition. For example, while major new courthouses have been built across the state, including in Bronx, Queens, Kings, and Richmond Counties, one of the last two courthouses constructed in New York County, 111 Centre Street, was built in 1960, over 60 years ago, and has not aged well, and the other, the New York Family Court at 60 Lafayette Street, was built in 1975 and has had problems of its own. The jewel that is the New York County Courthouse, which will celebrate its 100th anniversary in a few years, is in need of repair, as the authors discuss in an article about that great edifice written for the Historical Society. Work spaces in some older courthouses would not pass muster in the private sector. Maintenance and modernization by local governments appear to be falling short today in the cases of some older courthouses, the conditions of which contrast notably with the magnificent facilities of our federal court counterparts. The courts also face challenges that did not exist in 1987, such as those presented by magnetometers, security screening, and resultant lines of citizens awaiting access to some buildings, and by the mandates of the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990), particularly in regard to older facilities such as the New York County Courthouse. Work needs to be done to achieve fully for today and into the future Matt’s vision for modern, technologically-advanced, user-friendly court facilities throughout the entire far-flung court system.

[4] Deputy Chief Lippman remained in that position until 1996, after which he served as Chief Administrator (1996-2007), Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, First Department (2007-2009), and Chief Judge of the State of New York (2009-2015).

[5] Fourteenth Annual Report of the Chief Administrator of the Courts for the Calendar Year 1991, p. 6 (March 1992).

[6] As IAS evolved in the courts over the years, it became clear that there would not and could not be a single version thereof. Many courts struggled to achieve sound implementation of IAS and compliance with standards and goals applicable to case management before cases are ready for trial and after such readiness is accomplished. Variations of IAS tailored to the needs of different courts, localities, and case types developed across the state. One size can never fit all in this regard and the goal, as Matt understood so well, was and is to hone case management practices to the needs of different courts and types of cases. The IAS system was adversely affected to a certain degree by the coming and going of judges, changes in assignments, the ascension of judges to the Appellate Division, etc. The availability of adequate support from well-trained, experienced staff has been shown over these years to be critical to successful implementation of case management plans and such support has not always been in place, such as following workforce reduction programs in 2010 and 2011. Three decades after Matt left the court system, this effort remains a work in progress, and Matt very adroitly promoted the steps needed to achieve that progress.

[7] Judge Wachtler writes further: “Ed Koch, the then-Mayor of New York City, as well as other populist politicians, made it a practice to criticize and blame the crisis in New York City on ‘soft-hearted and soft-headed lazy judges.’ Because sitting judges are prohibited from responding to their critics, they become an easy prey for this kind of demagogic rhetoric. Whenever Koch took a swipe at the judiciary, his popularity soared, and he never missed an opportunity to tell his favorite story about a judge who was ‘liberal until he was mugged.’ These kinds of attacks brought him great polling numbers, but his disparagement affected not only the morale of the judges, but also the public’s confidence in our judiciary.”

[8] Elizabeth Kolbert, “Wachtler Says Cuomo Cut Judiciary Funds Unconstitutionally,” NY Times, April 11, 1991, p. B 5.

[9] See Annual Report cited in note 5 above, at p. 6.

[10] Judge Wachtler recalls that hundreds of non-judicial employees were furloughed. “Because the law compelled the ‘last hired to be the first fired,’ many young and recently married court employees who had just taken out mortgages were given ‘pink slips.’”

[11] Elizabeth Kolbert, “Fiscal Cuts Forcing Layoffs, Chief Judge Says,” NY Times, Sept. 6, 1991, p. B 3.

[12] Kevin Sack, “Cuomo and Chief Judge Settle Court Budget Fight,” NY Times, Jan. 17, 1992, p. B 4. The Annual Report of the Chief Administrator for 1991 described the reduction in court operations in detail. See Annual Report cited in note 5 above, at pp. 6-8.

[13] “Judge Wachtler Files His Suit to Get Courts More Money,” NY Times, Sept. 27, 1991, p. B 3. The Governor filed a responsive action in Federal court. Kevin Sack, “Cuomo Challenges His Chief Judge’s Lawsuit,” NY Times, Oct. 8, 1991, p. B 1. See Sam H. Verhovek, “No Truce So Far in Albany Fight on Court Budget,” NY Times, Oct. 17, 1991, p. B 2; Sam H. Verhovek, “Wachtler v. Cuomo: Duel of Ex-Friends,” NY Times, Oct. 29, 1991, p. B 1; “Wachtler Says New Budget Cuts May Lead to Release of Suspects,” NY Times, Nov. 29, 1991, p. B 4.

[14] See sources cited in note 12 above. The result was, in Judge Wachtler’s view, a victory for the courts. “We won that fight,” he writes, “and not only had the budget cuts restored, and the non-judicial personnel restored, we were also able to have funds added to our budget in order to provide long-needed salary increases.” Matt reported that the settlement reached included agreement that the Judiciary’s 1991-92 budget would not be cut and that the Governor would approve the Judiciary budget for 1992-93 at the same level with an additional $ 19 million. See Annual Report cited in note 5 above, at p. 8.

[15] Annual Report cited in note 5 above, at p. 8.

[16] Mitchell L. Bach & Lee Applebaum, “A History of the Creation and Jurisdiction of Business Courts in the Last Decade,” 60 Business Lawyer No. 1, p. 152 (Nov. 2004).

[17] Id. at p. 159.

[18] See Annual Report cited in note 5 above, at p. 12.

[19] See ww2.nycourts.gov/ip/ethnic-fairness/index.shtml.

[20] Annual Report cited in note 5 above, at pp. 9, 11.

[21] See Annual Report cited in note 5 above, at p. 15.

[22] See www.nycourts.gov/ip/justiceforchildren/index.shtml.

[23] “LI Owes Thanks to Matt Crosson,” Newsday – Long Island, Jan. 4, 2011.

[24] Judge Keating was the Administrative Judge of the New York City Criminal Court at the time. Prior to that, he had been, among other things, a chief assistant district attorney and the Criminal Justice Coordinator for Mayor Edward I. Koch. Later, he led the New York State Judicial Institute.

[25] Twentieth Annual Report of the Chief Administrator of the Courts pp. 36-37 (1997).

[26] See ww2.nycourts.gov/ip/adr/about-us.shtml.

[27] Quoted in the article cited in note 3.

[28] Article cited in note 23 above.

[29] Randi F. Marshall, “Putting Together LI Life Sciences Pieces,” Newsday, Sept. 28, 2022, accessible at www.newsday.com/opinion/columnists/randi-f-marshall/life-sciences-long-island-labs-tft8zf5e.