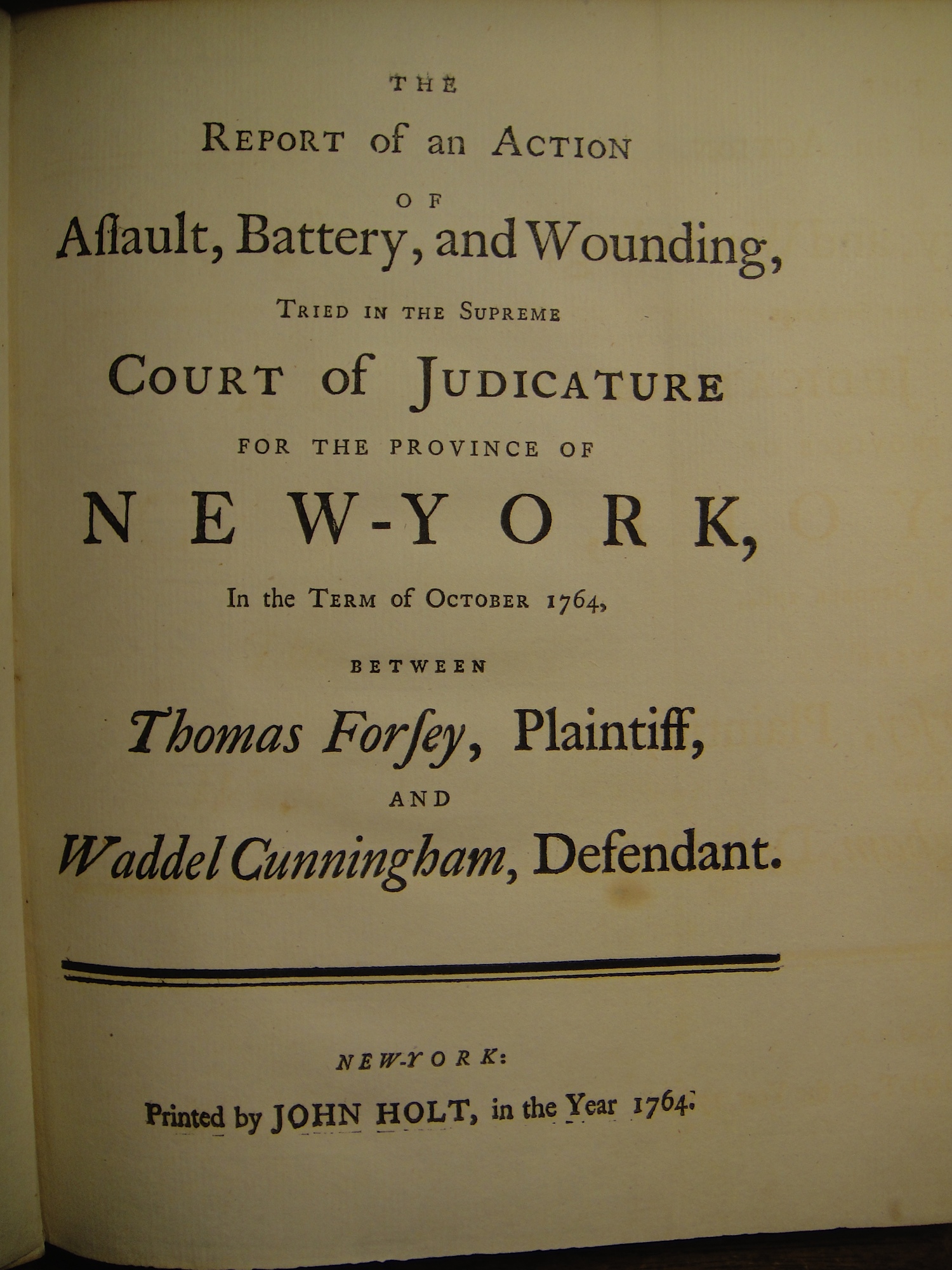

On July 29, 1763, an altercation broke out between two respectable business men, one armed with a sword and the other with a horsewhip. The dispute was over an unpaid debt of £150 and Cunningham, the creditor’s representative, seriously injured Thomas Forsey with the sword. Although Forsey’s life hung in the balance for some time, he eventually recovered. Cunningham was charged with criminal assault and, in January 1764, he was convicted and fined £30. Forsey then brought a civil action against Cunningham in the Supreme Court of Judicature, claiming damages of £5,000. On October 25, 1764 the trial commenced before Chief Justice Daniel Horsmanden and Associate Justices David Jones, William Smith (the elder), and Robert Livingston. A jury was empaneled and at the conclusion of the trial which lasted ten hours, returned a verdict in favor of Forsey and awarded him damages of £1,500. On October 27, 1764, the court reconvened. Cunningham’s attorney moved to set the verdict aside, but the court denied the motion and entered judgment for Forsey.

Under the common law, a judgment from a jury trial could only be reviewed by a writ of error bringing up for review issues of law but not of fact. But in this case, Cunningham apparently had an instruction from the King to appeal to the Lieutenant Governor (then acting Governor) and Council if the damages exceeded a certain amount. Cunningham presented a certified copy of the instructions to the court, but Chief Justice Horsmanden responded that “the King’s Instructions were to the Governor and that they were Judges of Law and not to be directed by any other Instructions.”

Disregarding the court, Cunningham went to Lieutenant-Governor Colden, who sought an opinion from Attorney General John Tabor Kempe. Kempe’s opinion was not supportive of Cunningham’s position but Colden nonetheless issued an order staying the judgment and a second order requiring the Supreme Court judges to appear before the Provincial Council to defend their denial of the appeal. Chief Justice Horsmanden defended the common law and argued that the representatives of the Crown did not have the authority to amend or reverse a jury verdict. Justice Smith stated that judges were “limited in their proceedings by the course of practice, in three of the great courts of law at Westminster, and no appeal from any verdict, taken in either of those courts, was ever known to have been allowed or entered there,” and Justice Livingston and Jones each maintained that an appeal lay only through a writ of error. Colden, who had no legal training, refused to accept any limitation on the royal prerogative.

The Provincial Council issued an opinion supportive of the judges of the Supreme Court of Judicature and Colden appended a dissenting opinion. Throughout the controversy, Colden had written frequent reports on the case to the Board of Trade in London. His opponents likewise brought their message to the authorities in England. On November 2, 1765, the English Attorney General and Solicitor General issued a joint opinion affirming that in a jury trial, an appeal could proceed only by a writ of error. The opinion arrived in New York in early 1776 and the challenge to jury verdicts in the Province of New York came to an end.

Further Reading

Henry M. Greenberg, “The Birth of Judicial Independence in New York.” New York Law Journal, Law.com (January 23, 2026).

Sources

Thomas E. Carney and Susan Kolb. The Legacy of Forsey v. Cunningham: Safeguarding the Integrity of the Right to Trial by Jury. 69 Historian, 663 (Winter 2007)

Daniel Joseph Hulsebosch. Constituting Empire: New York and the transformation of constitutionalism in the Atlantic World, 1664-1830 (2005)