B. The Life and Work of Rebecca Salome Foster

9. The Tombs and “Five Points”

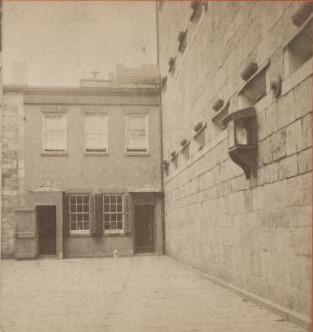

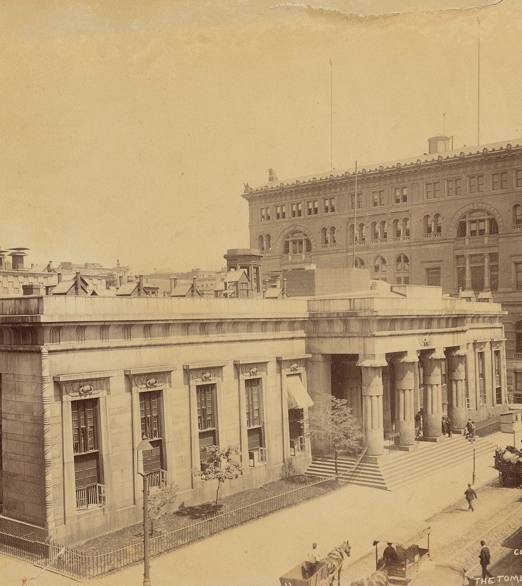

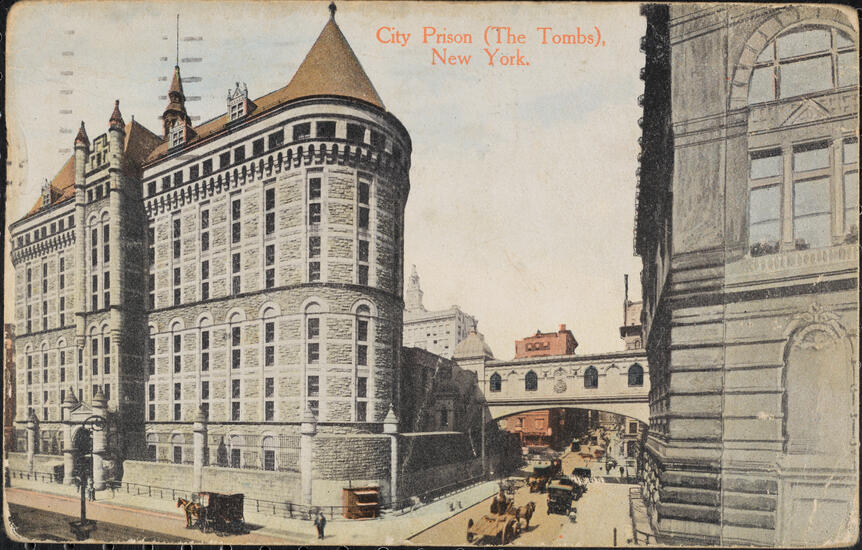

The original Tombs where Mrs. Foster worked daily was built between 1835 and 1840 and was known officially as “The Halls of Justice and House of Detention.” It replaced a pre-Revolutionary War prison in City Hall Park that was torn down in 1838. The new structure occupied a full block on the west side of Centre Street between Elm (today’s Lafayette), Leonard and Franklin Streets (the former location of the Tombs is today the site of Collect Pond Park),[163] and also housed the quarters of the Court of Special Sessions and the Police Court, which dealt with offenses to public order such as public drunkenness. The prison quickly became known as “the Tombs” because of its Egyptian Revival-style architecture, a name that has been used for its successors up to the present day.

The builders of the prison chose poorly when they decided to construct it where they did, on the former site of Collect Pond, which is depicted in an illustration in Section B (2) of this article, and which derived its name from a corruption of a Dutch word for “small body of water.” This substantial pond, in places 60 feet deep, and fed by an underground stream, was the source of the City’s drinking water in the colonial period. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the pond was a favorite spot for picnics and ice skating. In 1796, one of the first experimental steamboats was launched on the pond. By the early 19th century, however, the City had allowed commercial enterprises, including tanneries and a slaughterhouse, to locate at the pond and use its waters. As a consequence, the pond became polluted and it was filled in and leveled by 1813. Unfortunately, the filling of the pond was badly done. The site of the former pond emitted noxious odors and mosquitoes bred there happily. The deterioration of the area caused a decline in the value of property there and made the zone one ripe for the development of a slum.[164]

The construction of the new prison was not adequate for the conditions at the site.[165] The Tombs was dark, dank, and, thanks to the former pond, more than damp. Only months after the Tombs opened, the building began to sink, causing cracks in the foundation through which water leaked, forming pools on the floor. The prison was plagued by water problems from then on. Difficulties with the building persisted for years. More than once a Grand Jury condemned the structure as unhealthy and unfit for its purpose.[166]

The Tombs was primarily a place of detention for those awaiting trial and not released on bail. By the 1880’s, if not before, the prison was overcrowded.[167] But the prison also had a secondary, quite solemn purpose — executions by hanging took place inside the Tombs. A bridge that connected the women’s section to that of the men was known as the “Bridge of Sighs” because condemned men passed over it on their way to their execution.[168]

One writer described the Tombs as “this home of the wretched”:

For a half century The Tombs has been a synonym for sin and suffering. Here every suspected criminal is taken while awaiting trial and sentence. Here criminals have become still more hardened in their sinful career, and here, too, many a person, the victim rather than the guilty person, has become disheartened… Over the heavily barred gateway of this prison might well be engraved the words: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.”[169]

Charles Dickens came to New York City in 1842 and, not being a typical tourist, he paid a visit to the Tombs, which he described as “this dismal-fronted pile of bastard Egyptian, like an enchanter’s palace in a melodrama …” [170] Dickens was well familiar with prisons and the harshness of aspects of life in the 19th century (his father had been imprisoned in the Marshalsea Prison for failure to pay his debts when Charles was 12 years old (about which Charles wrote in Little Dorrit (1857)), at which point the boy had been forced to leave school to work in a factory). Still, Dickens was shocked by what he saw inside the Tombs. He wrote:

What! do you thrust your common offenders against the police discipline of the town, into such holes as these? Do men and women, against whom no crime is proved, lie here all night in perfect darkness, surrounded by the noisome vapours which encircle that flagging lamp you light us with, and breathing this filthy and offensive stench! Why, such indecent and disgusting dungeons as these cells, would bring disgrace upon the most despotic empire in the world![171]

Of the prison yard he wrote:

The prison-yard in which [a jailor] pauses now, has been the scene of terrible performances. Into this narrow, grave-like place, men are brought out to die. The wretched creature stands beneath the gibbet on the ground; the rope about his neck; and when the sign is given, a weight at its other end comes running down, and swings him up into the air — a corpse.[172]

Herman Melville in his famous story about the mysterious, phlegmatic, and taciturn Bartleby the scrivener had the Wall Street attorney who narrated say of the Tombs that “[t]he Egyptian character of the masonry weighed upon me with its gloom.” In keeping with that gloom, in the concluding section of the story, Bartleby was carried off to the Tombs as a vagrant at the instance of his landlord, declined to eat his food, and died in the yards of the prison.[173]

Apparently, Mark Twain also understood that the Tombs was a widely-recognized symbol and reality of harsh or at least rigorous treatment of persons suspected and accused of crime. In the novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873), which gave its name to the entire era, Twain and his co-author, Charles D. Warner, have one of the principal characters, who gets into grave trouble with the law, incarcerated there.

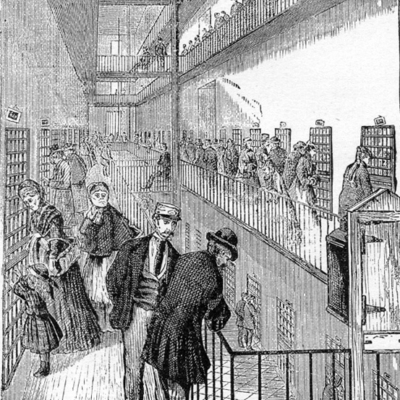

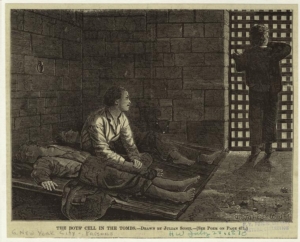

We get a very clear understanding of what conditions were like inside the Tombs during the years when Mrs. Foster was working there from a report issued in 1896.[174] The Prison Association of New York was required by law to inspect the prisons in New York State and to report annually to the Legislature on what it found. A committee of the Association inspected the Tombs for two days in 1895. At that time, there were three facilities inside the Tombs: the original structure and two much smaller prisons, one holding alleged petty offenders and the other women and boys. The committee noted that cells in the main facility had been constructed against the walls and opened on a central court, as can be seen in some illustrations that appear in this section and in Section B (7) of this article. There were four tiers or stories of cells, with a narrow gallery running outside the cells on each tier overlooking the court. Each cell was about ten feet long and six feet wide, with a single bed about three feet wide.[175] The arrangement of the cells precluded the admission of adequate light and ventilation from outside the walls. There were narrow slits through the rear wall, but the air and light inside the cells came principally from the central court through the grated doors. The prison was, still, 60 years after its opening, “dark, damp and ill-ventilated.”[176] There was an uncovered water closet in each cell, and these, the committee members found, “are old, rusty and more or less dirty and offensive. The cells are dark, ventilation is necessarily defective, and the smell, characteristic of a badly ventilated prison, is always present.”[177]

The prisoners were allowed no exercise in a yard or the open air. Exercise in the Tombs consisted of this: the prisoners were allowed out of their cells twice a day for an hour and permitted to walk around the gallery outside the cells. The rest of the day, 22 hours a day, they were locked in the cells.[178]

There were 298 cells in the prison. During the committee’s visit there were about 470 prisoners detained, which was the typical number. Thus, most of the cells housed two prisoners each, but some would not infrequently accommodate three.[179]

In the cases where two or three men occupy one of these cells, they pass twenty-two hours of the day in this cell together. The cell contains no chair or table. There is no place to sit down except upon the narrow bed. They sleep together in this narrow bed, usually lying one with his head at one end of the bed and the other with his head at the other end, whenever two occupy the cell; when there are three occupants, the third man lies on a mattress or blanket on the floor. And in such a cell they remain, in some instances for months, day and night, in the cold of winter, and the sweltering heat of summer, breathing the foul air of the prison, and the fouler exhalations from the closets in the cells.[180]

The permanent overcrowding of the cells “is nothing but a means of indescribable torture to a decent man, and a prolific school of vice and crime to a criminal.”[181]

There were no decent bathing facilities in the prison, only a rusty old tub in one cell on each floor. There was no employment or activity for the detainees of any sort, nor adequate hospital facilities. All meals were taken in the cells, without the benefit even of a table on which to place plates and utensils. The prison was “defective in every modern appliance.”[182]

The members of the committee did not employ euphemisms in stating their opinion of the conditions they saw.

Such treatment of dogs would be gross cruelty; and when it is considered that the men so treated have not been convicted, and in many instances never are convicted of any crime, and that the prison is only intended to be a place for safe detention and not a place for punishment, no language which can be employed can be too severe in denunciation of such an infamy.[183]

“The provisions for women prisoners,” the committee found, “are entirely inadequate; and in short, almost everything about the design and arrangement of the Tombs prison deserves unqualified censure.”[184]

The committee therefore concluded that no attempt ought to be made to refurbish or utilize the Tombs. “The Tombs prison, as it has existed for years past, is a disgrace to the city of New York. It ought to be immediately demolished. It cannot be made decent.”[185] A new facility, the committee recommended, one “designed as a place of safe detention and not of punishment, and built in accordance with modern ideas of prison construction,” should be put up in its place.[186]

Unlike many another governmental report, this one, by itself or perhaps in conjunction with others of like tenor, achieved results: the old Tombs was demolished. A new prison was built at the same location in 1902.[187] In 1894, a Criminal Courts Building, also situated on the west side of Centre Street, had been constructed across Franklin Street from the original Tombs. The new Tombs was connected to the court building by another “Bridge of Sighs” to ease the transfer of detainees to the court for legal proceedings.

It is nothing short of amazing that Mrs. Foster spent each day of the entirety of her career working, without recompense, in the horrible conditions of the Tombs described by the Prison Association committee.

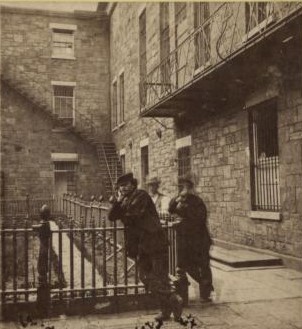

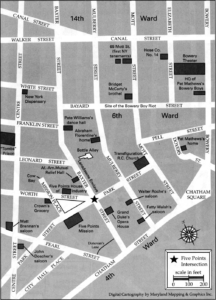

The wretchedness with which Mrs. Foster contended every day was not confined to the interior of the Tombs prison. The neighborhood very near the original Tombs, in which Mrs. Foster spent so much time, which today is Foley Square and environs, was then an impoverished district largely of immigrant housing, of shabby and crowded tenements and extreme poverty, and of the social problems, crime not the least of these, to which such conditions give rise. The neighborhood, of Gangs of New York fame, was known as “Five Points,” taking that name from an intersection of streets that produced five corners, and it was thoroughly infamous, and not just throughout New York City. The great influx in immigration to the United States that we described earlier had perhaps a greater impact on this district than any other in New York State, or even the country. One scholar has written of it that “Five Points was the most notorious neighborhood in nineteenth-century America:”

Beginning in about 1820, overlapping waves of Irish, Italian, and Chinese immigrants flooded this district … Significant numbers of Germans, African Americans, and Eastern European Jews settled there as well … [T]he densely populated enclave was once renowned for jam-packed, filthy tenements, garbage-covered streets, prostitution, gambling, violence, drunkenness, and abject poverty. “No decent person walked through it; all shunned the locality; all walked blocks out of their way rather than pass through it,” recalled a tough New York fireman. A religious journal called Five Points “the most notorious precinct of moral leprosy in the city, … a perfect hot-bed of physical and moral pestilence, … a hell-mouth of infamy and woe.” [188]

Dickens visited the Five Points, which he described in the following words:

Poverty, wretchedness, and vice, are rife enough where we are going now.

This is the place, these narrow ways, diverging to the right and left, and reeking everywhere with dirt and filth. Such lives as are led here, bear the same fruits here as elsewhere. The coarse and bloated faces at the doors, have counterparts at home, and all the world over … See how the rotten beams are tumbling down, and how the patched and broken windows seem to scowl dimly, like eyes that have been hurt in drunken frays …

What place is this, to which the squalid street conducts us? A kind of square of leprous houses, some of which are attainable only by crazy wooden stairs without …

Here too are lanes and alleys, paved with mud knee-deep, underground chambers, where they dance and game; the walls bedecked with rough designs of ships, and forts, and flags, and American Eagles out of number: ruined houses, open to the street, whence, through wide gaps in the walls, other ruins loom upon the eye, as though the world of vice and misery had nothing else to show: hideous tenements which take their name from robbery and murder; all that is loathsome, drooping, and decayed is here.[189]

The Tombs was a part of this area, located only a short distance from the Five Points intersection. To reach the intersection from the Tombs one only needed to walk one block south on Centre Street, turn left onto Worth Street, and proceed one cross-town block. Many of those who were incarcerated in the Tombs and who looked to Mrs. Foster for assistance, and the families of those persons, came from this impoverished neighborhood. Thus, Mrs. Foster’s work in the Tombs and her labor on behalf of the detained required that she frequent the neighborhood and its facilities on a daily basis. The ground-breaking publication of Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York in 1890, when Mrs. Foster was working there, shed unsparing light upon the harsh conditions of the area, which are visible today in Mr. Riis’s surviving photographs, including of the inside of the Tombs.[190] The faces of many poor immigrants and others who lived in the Five Points neighborhood now stare out at us from the streets and buildings and rooms photographed by Mr. Riis, and the modern viewer can only wonder how these persons endured such conditions. But they did, and they continued to do so for some considerable time before the work of Mr. Riis, Theodore Roosevelt, and many others led to the elimination of the Five Points tenements.

In working each day in the Tombs Prison, and walking the streets of the Five Points neighborhood on a daily basis, which almost no one else of her social station would have done or did, and doing her work in the wretched and dangerous tenements, saloons, and other establishments of the area, Mrs. Foster demonstrated clearly that she was a person of exceptional determination, dedication and courage.

Table of Contents

A. Introduction

B. The Life and Work of Rebecca Salome Foster

- The Backgrounds of Rebecca and John A. Foster

- New York City in the Late 19th Century

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Began

- What Mrs. Foster Did for Prisoners, Their Families, the Courts, and Others

- Mrs. Foster’s Work in Her Own Words

- Funding the Work

- Providing Legal Assistance

- Traveling Throughout the City and Elsewhere

- The Tombs and “Five Points”

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Came to an End

D. What Happened to the Memorial

E. The Foster Family and a Home for the Marble Relief

G. Endnotes