B. The Life and Work of Rebecca Salome Foster

1. The Backgrounds of Rebecca and John A. Foster

Not a great deal is known about Mrs. Foster’s early life. She was born in 1848 into the large family of John Howard Elliott, a native of Great Britain who worked as a merchant, and Margaret Adele (Blue) Elliott of Mobile, Alabama. Rebecca was one of nine children, mostly daughters (although, as was unfortunately all too common for the time, not all may have survived into adulthood).[2] In 1850, the Elliott family was living in New Orleans. By 1860, the family had moved to New York City. The Elliotts relocated to Westchester County, or at least were recorded as living there in the summer of 1860, possibly as an escape from the summer weather of the City.[3]

On February 28, 1865, in Calvary Episcopal Church, 277 Park Avenue South at 21st Street in the Gramercy Park neighborhood of Manhattan, Rebecca married John Armstrong Foster.

John Foster was born in Schoharie County, New York, in 1833, the son of a physician who practiced in New York City for over 50 years.[4] John Foster served in the Civil War for a period and then, in 1862, when he was only 29, he took part in the raising of the 175th Regiment, New York State Volunteers, an infantry regiment, and served as a Lt. Colonel. Among other things, the regiment was engaged in operations in Louisiana and, in 1863, in the siege and assault against Port Hudson, the success of which, after the taking of Vicksburg, freed the Mississippi River for the Union. In this action the regiment’s commanding officer was killed and Foster was promoted to Colonel.[5] In 1864, the regiment participated in General Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign.[6]

Foster was an attorney. In early 1864, he was assigned to the Bureau of Military Justice in the War Department in Washington, which was presided over by the Judge Advocate General, General Joseph Holt.[7] Among the duties of the Judge Advocate General’s office was to administer military justice, including the prosecution of courts martial.[8] In or about February 1865, Colonel Foster served on, or acted as prosecutor in matters before, a commission that adjudicated court martial proceedings in Philadelphia, from which he may have taken some time off to head north to get married. This commission was chaired by the distinguished career Army officer, West Point graduate, and veteran of Fort Sumter, Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg, Major General Abner Doubleday of upstate New York.[9]

Two days after the assassination of President Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton designated three officers from the War Department to take leading roles in the investigation of the conspiracy that led to the crime, even while the military and detectives were searching for the conspirators and John Wilkes Booth was being pursued in Virginia. Colonel Foster was one of these officers.[10] He collected evidence, analyzed it, considered the possible culpability of witnesses and suspects, developed a theory of the case, directed the incarceration of suspects[11] and performed other activities to build the case. Secretary Stanton also designated a Judge Advocate from the west, Colonel Henry L. Burnett, to oversee preparation of the case for trial and ordered him to Washington to work directly under General Holt.[12] Colonel Foster provided evidence and prepared reports for Colonel Burnett in which, among other things, he described the actions of Booth, George Atzerodt, and other suspected conspirators on the day and night of the assassination, at Ford’s Theater and elsewhere in Washington and environs, and in the days afterward.[13] General Holt was the lead prosecutor at the trial of the Lincoln conspirators before a military commission and Colonel Burnett was his principal deputy at the trial.[14]

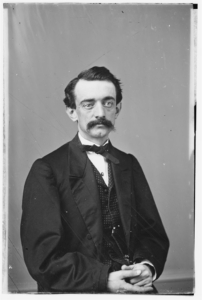

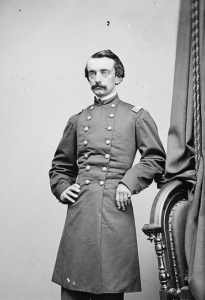

Foster officially left the Army in August 1865 and was brevetted as a Brigadier General in recognition of his distinguished service.[15] The Library of Congress has photographs of Foster, including in uniform, which are reproduced in this article, that apparently were taken by Mathew Brady or his assistants.

After the war, John Foster practiced law in New York City. He served for a time as an Assistant United States Attorney, was active in the Republican Party,[16] and was the senior member of a law firm, Foster, Glassey & Thomas, which had offices at 229 Broadway in Manhattan.[17] Rebecca Foster would on occasion assist him with his practice, including when he was appearing in court. The fact that her husband earned his living in the legal world directly contributed to the kind of work that Mrs. Foster chose to do.

Calvary Church played a central role in Mrs. Foster’s life and in the work she undertook on behalf of persons accused and convicted of crime, their families, and other outcasts. As she had done, her two daughters, Marie Louise and Jeanette, married at Calvary Church, in 1892 and 1893, respectively.[18] Mrs. Foster was, it appears, always a giving person. In 1878, for instance, she was the principal organizer of a fair to raise money for charity in New York City.[19] It seems that her good works on behalf of prisoners arose out of her church associations and were inspired by the Anglican missionary movement, which exerted significant influence in the last half of the 19th century. Of course, Christian missionaries, Catholic and Protestant, traveled to the far ends of the earth during those years and after, but they ministered locally as well. Many members of the laity sought to put their religious and ethical principles into action in the world by helping the poor of the cities. These workers conducted their efforts as extensions of their churches, in the settlement house movement of that time,[20] and in independent ventures.

An important spiritual advisor to Mrs. Foster was Rev. Henry Y. Satterlee (1843-1908), who from 1882 until 1896 was the rector of Calvary Church. During those years, Rev. Satterlee was active in mission work to the masses of poor then living on the city’s Lower East Side. In 1896, Rev. Satterlee was named the first Episcopal Bishop of Washington, D.C., but he maintained many of his associations in New York City, including that with Mrs. Foster. Rev. Satterlee is credited with founding the Cathedral Church of St. Peter and St. Paul, more commonly known as the National Cathedral, acquiring the property on which the Cathedral was built and overseeing its early construction. He performed the marriage ceremony for both of Mrs. Foster’s daughters at Calvary.[21]

The Rev. Mr. Satterlee was a powerful advocate for his faith and recruited many men and women to his congregation.[22] The power of his word was forcefully brought home to Mrs. Foster at a time of severe crisis in her life. Mrs. Foster had suffered a great tragedy in 1867, when her daughter, Lomie Elliott, died at age two. The grief this disaster brought on was compounded later, in 1878, when her only son, John Armstrong, died at age five.[23] The Rev. Mr. Satterlee’s biographer wrote of Mrs. Foster:

Her faith staggered and she drifted out into the gloom of unbelief. She was persuaded to see Dr. Satterlee. With his wise and understanding sympathy he threw a ray of hope into her life. She began to attend church to hear him preach. He invited her to come to his Monday meeting of workers among the poor. By degrees her faith reasserted itself as an active force impelling her to service.[24]

These events transformed Mrs. Foster’s life and appear to have helped greatly to set her on the course she was to follow for the whole of her life thereafter.[25]

Her life of service, then, was an outgrowth of her religious faith and her response to hardship and loss. She understood well what it means to suffer, and she felt kinship with, and compassion and sympathy for, others who had endured suffering too, including those, such as the vast numbers of immigrants on the Lower East Side, whose circumstances were decidedly different from her own. And yet, there was more behind her life’s work even than these things. She undertook her work also as a reflection of her gratitude for what life had given to her, because, she said, “at that time I and my family had everything to be thankful for in the world …”[26] At a certain point, she said, “I resolved that if I could save but one woman, my life would have been well lived.”[27]

After her work began, however, the life of her family took another tragic turn. In time, General Foster came to practice law alone because, it appears, “[h]e had contracted habits which proved his professional and social ruin, and he could no longer be tolerated by his partners … [H]is desire for drink gradually lost him nearly all his friends.”[28] It was reported that he had become mentally irresponsible by 1887. The following year, without reason, he abandoned his family “and wandered about aimlessly, lodging at haphazard.”[29] In September 1889, he met his former orderly from the army, who gave him shelter in a two-story frame building behind his insurance office on upper Broadway. The orderly let him sleep on chairs covered with an army blanket as there was no bed in the place. Foster died alone in that space in February 1890.[30] Mrs. Foster had taken to dressing in black after he had abandoned the family. Sadly, a reporter noted, she was thus “fitly attired yesterday when she went to the office where her husband’s body lay.”[31] She brought a large bouquet of flowers with her. When speaking with the coroner, “she fainted away, and excited much sympathy.”[32] General Foster was only 57 years old. Mrs. Foster applied for a pension as the widow of a Union soldier.[33]

Table of Contents

A. Introduction

B. The Life and Work of Rebecca Salome Foster

- The Backgrounds of Rebecca and John A. Foster

- New York City in the Late 19th Century

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Began

- What Mrs. Foster Did for Prisoners, Their Families, the Courts, and Others

- Mrs. Foster’s Work in Her Own Words

- Funding the Work

- Providing Legal Assistance

- Traveling Throughout the City and Elsewhere

- The Tombs and “Five Points”

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Came to an End

D. What Happened to the Memorial

E. The Foster Family and a Home for the Marble Relief

G. Endnotes