B. The Life and Work of Rebecca Salome Foster

4. What Mrs. Foster Did for Prisoners, Their Families, the Courts, and Others

After the accidental commencement of her career, Mrs. Foster’s activities quickly expanded beyond the provision of information to the judges upon request about the background and actions of the defendant, beyond what might be characterized using current terminology as a kind of oral pre-sentence report. Indeed, we see the germ of this growth in Mrs. Foster’s actions in the very first case she had. In addition to providing the judges with background information on defendants, she also came to offer in appropriate cases means of supervision of and assistance to the defendants as an alternative to incarceration or perhaps after the completion of an abbreviated sentence. Judge Jerome said:

[F]requently, before the prisoner was convicted, [Mrs. Foster] would make an investigation, and if judgment was suspended she would, especially in the case of young women, take them into her charge, procure situations for them, and exercise a general supervision over them for a considerable time, helping them wisely. She had a little place, up somewhere on the Sound, where she took some of these. For others she would procure lodgings, and frequently, when a woman was sentenced and sent to prison, she would look out for her children; and where men were sentenced she would look out for their wives, procure means to help them — give them food and clothing, procure work for them. [53]

What Mrs. Foster did was to provide the court, in cases that she judged to be suitable and where she demonstrated that suitability to the court, a way to sentence defendants that would not be unduly harsh and punitive, but that rather could, while protecting society, provide a chance that the defendant could be induced to forgo or abandon a life of crime. Without the information Mrs. Foster made available and the steps she took in suitable cases to offer a realistic pathway to a better life to the defendant, the court might have been forced to impose on defendants penalties that were too severe: as in that first case, the judge might recognize that the options available could be too hard upon the defendant, but, without Mrs. Foster’s help, lack a mechanism to tailor the sentence to the real equities of the situation. Mrs. Foster became an advocate, in suitable cases, for alternatives to incarceration and for the rehabilitation of defendants. Mrs. Foster’s approach was innovative and visionary, prefiguring the rehabilitative model of penology that became widespread in the decades after she had completed her work.

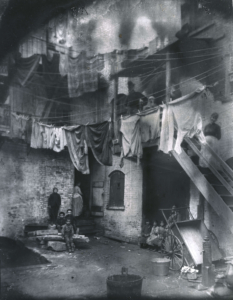

Mrs. Foster became in a short progression a one-person combination of social services agency, probation office, parole office, and legal aid society working on behalf of the court and the accused and those who had been convicted, as well as their families — and, of course, just as is the case today, the incarceration of a family member who had been bringing in income to sustain the family would be a catastrophe for the entire family — this at a time when government services for the poor were either non-existent or rudimentary, and private, non-profit and charitable endeavors, though growing, were far less extensive than they are today. The Legal Aid Society of New York, for instance, was established in 1876 to provide legal assistance to low-income German immigrants; its remit expanded to the provision of legal assistance to all in need only in 1896.[54] With the great influx of immigrants in those days, this was also a time in which many of those with whom Mrs. Foster came into contact lived in very precarious circumstances, when not much error or misjudgment was required to cast a person and his or her family into dire economic trouble. In part, Mrs. Foster’s work presaged the role of professional probation officers, who were only introduced in New York pursuant to legislation after 1900.[55] Thus, the judges came to depend upon Mrs. Foster not only for information about the backgrounds of defendants, but also for guidance about and assistance with possible placements for the defendant outside of prison, arranged and undertaken by Mrs. Foster, that might facilitate the prisoner’s reclamation.

Meticulous, energetic, and fair investigation of the facts, a willingness to believe where warranted in the accused’s potential for reclamation, and the development of concrete measures that could be taken to assist the defendant to turn away from crime were central to Mrs. Foster’s work, as was noted by a friend of hers:

She makes such careful and thorough investigation of every case she undertakes to help, that she can often present facts that would be otherwise entirely unknown to judge and jury … Very often, after the trial of a woman or young girl, the judge gives her, either under suspended sentence, or without sentence, into Mrs. Foster’s custody, when she is immediately taken to some safe temporary shelter, from which she can either find work or be sent to her home.[56]

Two accounts described her activities as follows:

She visited the courts almost daily, and visited the cells of the women prisoners whenever there was hope of doing good. There were times when the justices doubted her wisdom and feared that her womanly sympathy would overbalance her judgement. Then detectives were sent to supplement her investigations, but the fact that the court continued to appeal to her for help and that the Justices of the criminal courts welcomed her aid, proves that such fears were groundless. The quiet little woman … came… to be regarded by justices and prisoners alike as a veritable sunbeam amid murky courts and prison surroundings.[57]

* * *

[The prison work of] Mrs. Foster began with some casual visits to the Tombs, with no thought that so many of the later years of her life would be spent in that building and in this work of rescue … Though there was no probation law in operation at that time, she practically fulfilled all the duties of such officer. She secured the confidence of prison officials and of the judges. She was intrusted by the latter with the investigation of cases, mainly of girls and women committed for various offences. The greatest reliance was placed in her judgment, and under the power of the judges to suspend sentence, many cases were practically placed in her custody. She gave freely of her money as of her time and strength to help needy prisoners.[58]

Mrs. Foster did not merely make herself available to the court when called upon, but often initiated applications to the court to provide assistance to the defendant. Thus, she became an advocate for accused persons who, in her judgment, were open to being helped, which was a groundbreaking role for a woman at a time when there were very few women attorneys in the United States. A reporter wrote in 1891 that “[i]f she steps forward and asks the Justice to release the woman or to commit her to such or such an asylum or retreat, her request is pretty sure to be granted, for her opinion is respected.”[59] Thus, we find, for example, the case of Jennie Purcell, who was convicted of grand larceny. When the judge came to sentence her, he said the following: “You have a bad record on the Bowery. I fear it is impossible for you to reform. But Mrs. Foster tells me she will care for you, so I will let you go.”[60] And:

— Mrs. Foster appealed to the court in favor of Lucy Davis, who had been charged, along with another girl, both of them from Mott Street, with abduction. Mrs. Foster found that Davis had a respectable sister residing in the city, who agreed to take her in. The court discharged Davis, and the other girl as well.[61]

— Mrs. Foster spoke up in court in favor of Clara Marks, who had run away from her home in New Haven and been picked up in New York after she had been deserted by a man who had promised to marry her. At the request of her parents, the girl was sent to a reformatory for six months; Mrs. Foster accompanied her there.[62]

— Mrs. Foster spoke to the court in favor of a young girl who had been charged with shoplifting two pairs of cuff buttons, a first offense. The court suspended sentence and the girl was released.[63]

Thus, it was, thanks to Mrs. Foster, for very many.

Mrs. Foster considered her work, in cooperation with the judges, as that of “encouraging the discouraged, helping the families of men sent to prison, getting work for those who are discharged and looking after girls and women whose sentences have been suspended, and for whom she is made responsible by the justices …” [64]

Mrs. Foster felt a particular concern for young girls and women who had never previously been in trouble with the law. She recognized that a first offense, or an accusation thereof, was a decisive moment for the girl or woman, that her entire future life could be determined for ill or good by how she was treated by the system of justice at that point. Such an accusation or offense constituted a grave danger, but also presented a great opportunity for permanent reclamation; if the opportunity were not seized, the life of the girl or woman could easily be destroyed forever in hopeless crime and degradation.

Her object is to soften every evil-minded woman’s heart, and to have her so disposed of that the influences around her will be for the best. There is no woman so depraved that Mrs. Foster will not attempt to save her. What she regards as her special mission, however, is the influencing of women who are involved with the law for the first time and who therefore stand in a very critical position.

A first arrest, Mrs. Foster believes, is often the turning point of a woman’s career. She may not have been bad before, only foolish, careless, reckless, or unfortunate, but now she may go down. But taken in time, here in her trouble, when she most needs a friend, she may be switched upon the right track for good and all.[65]

Although, as we have noted, her religious faith provided an inspiration and a foundation for her efforts, Mrs. Foster’s goal was secular, not the conversion of souls. Mrs. Foster extended assistance without any regard to the religious orientation, if any, of the person she aided and without using her aid as an occasion to proselytize on behalf of her faith.[66] The District Attorney stated that “[t]o all, Jews and Christians and those of no faith, she extends a helping hand.”[67] The Rev. Mr. Munro wrote that she would “help everyone in time of need, regardless of creed, color or race.”[68]

The infamous Tombs Prison — why it was infamous we explain later — was the principal situs of her work. “The prisoners from all the police courts, if held for trial, eventually come to the Tombs prison, so this is naturally her base of operations… Even the jailers in the prisons attached to the police courts send to the Tombs for Mrs. Foster sometimes when they have unmanageable women in their care whom they think she would like to see.”[69] She also worked in the Court of Special Sessions and other courts, where she would make her applications and reports to the judges presiding over cases of interest to her and to the court.[70]

In order to gather facts for her investigations and identify candidates for release without sentence or after a suspended or reduced sentence and placement into her custody, Mrs. Foster spent much time in the prison with the accused, inquiring into their backgrounds and providing encouragement. She also collected information about the financial condition of each accused’s family and would extend financial assistance to the family when needed (it often was). She would provide food, clothing, travel expenses, shoes, financial aid, and other assistance to the defendants and their families. She was, Chaplain Munro wrote, “a very charitable lady, and in course of a year gave away much money, clothing, shoes and railroad tickets and meals, to hundreds of men and women as they came out of prison.”[71] Frequently, she would attend legal proceedings as the friend of the defendant.

Mrs. Foster paid close attention to obtaining decent clothing for the prisoners whom she helped. “Many of those arrested are innocent of the crime charged,” she said, “yet a ragged, dirty boy looks more likely to be guilty than innocent, and the clean clothing with which I am able to supply him … may make all the difference between a favorable and an unfavorable impression on the Court. Many a young girl, too, has been saved from dropping into degradation by the gift of neat clothing that enabled her to look for work.”[72]

Another report described her work in this way:

She worked especially among the women prisoners at the Tombs, giving them advice, questioning them, and, where she found worthy cases, appealing to magistrates in their behalf. She was often instrumental in gaining for those for whom she recommended judicial mercy release from custody and a new start in life. She visited police courts, and was known and trusted by many magistrates, who treated her with great courtesy … Because of the character of the woman, it has been said that nine times out of ten if she spoke to a magistrate in a prisoner’s behalf the latter would be discharged.[73]

Mrs. Foster was in the Tombs so often — “every morning, regular as clockwork,” according to the Sheriff [74] — that she became a fixture of the place.

In the Tombs prison Mrs. Foster has always had as much freedom as the Warden himself. She is known to every employee in the place and goes in and out whenever she pleases. Matrons and keepers stand ready always to do anything they can for her, and as a result she is able to do a kind of work among the unfortunates confined there that would be impossible did she not possess the absolute confidence of the authorities.

Mrs. Foster sometimes makes as many as twenty visits in a day to the prison, and seldom falls below five. Every morning regularly she makes an early call to find out what new cases have come in, and whether among the newcomers there is anybody to whom she can be of use. It isn’t necessary for her to consult the prison books to find out what she wants to know. The keepers and matrons keep their eyes wide open for cases for her, and she is in possession of all the news of the prison each morning before she has been in it five minutes. If there is a young girl in the female prison she goes in and sees her. She has never failed to make a friend where she has tried to, and few of those she has talked to have failed to be penitent, for a time anyway. Even the most depraved of the female prisoners, those who spend half their lives in the prison and are far beyond rescue, have a pleasant “Good morning” for her when she enters the prison. [75]

Various religious denominations had a presence in the Tombs, and religious services were conducted in a chapel on the premises. But the religious groups that led those services and their members were generally perceived by the prison authorities as “do-gooders,” rather naive and not helpful. Mrs. Foster, on the other hand, was revered by the judges and prison authorities for her honesty, sagacity, and integrity, the soundness of her judgment, and her very practical, very constructive methods and ideas. The religious groups might preach to the incarcerated and urge them to choose a life of goodness; Mrs. Foster, by contrast, provided concrete and realistic means and tools — training, financial assistance, housing, gainful employment — that could set the accused and convicted on a course to a law-abiding life.

After her husband’s death in 1890, Mrs. Foster devoted herself to her occupation all the more intensively. Her daughter remarked that she “cannot remember the time when mother was not engaged in some charitable work or other.”[76] The Warden of the Tombs said that “no one unacquainted with the details of Mrs. Foster’s work will ever know the self-sacrificing life that she led …”[77] One of Mrs. Foster’s friends wrote that she “devoted every day in the year” to the work.[78] Mrs. Foster was so dedicated to her work, and so effective in it, that not long after she had begun she became widely known among her beneficiaries, judges, prison and court personnel, and others, including her fellow parishioners of Calvary Church, by the name “the Tombs Angel,” an informal honorific initially bestowed, it appears, by the prisoners. One of the judges said of her that “[s]he was not only a ‘Tombs angel,’ but a court angel.”[79]

Inevitably, Mrs. Foster’s activities in the courtrooms of the city became known outside the courts. In time, all the newspaper reporters of the city learned about Mrs. Foster’s work, and, though by no means a naïve bunch, they came to respect her. The attention, however, made her uncomfortable and she sought to persuade the reporters against publicizing her work and her cases.[80] One reporter wrote of her in 1891 that “[t]he first object of her life is to help women in misfortune. Her second object seems to be to avoid publicity.”[81] “[H]er influence has frequently been of service in keeping out of the press things that would have been harmful [to the person she was trying to aid] if they had been given notoriety.” “‘Boys,’ she would say, ‘it’s only a poor girl that has gone wrong, and you know that notoriety in her case will undo one-half of what I can do to put her right again. Leave it out, won’t you?’ And in a majority of cases she had her way.” [82] But if her pleadings to reporters to keep a case out of the newspapers appeared to fail, she would then ask that the reporters at least keep her own name and role out of the story. “‘It will interfere with my work,’ she would say.” [83] One reporter, noting “her extreme reticence about her work,” wrote the following about her appeal to him and his colleagues when she began her work:

When she first began … she called the reporters together and said it would be impossible for her to go on with the work if they were going to make “stories” out of her. She asked that she might never be mentioned when it was possible to avoid it. She never talked about her work among her friends and with her family, and her life in the courts and the Tombs was lived quite apart from her life at home and in society.[84]

Mrs. Foster started her day with services at Calvary Church and went from there to the Tombs.[85] The sexton of Calvary Church reported that at these morning visits there would usually be people in need, sometimes as many as 20 or 30, waiting there for her, hoping for help, including impoverished persons not in trouble with the law. “She used [the church] as her uptown office, and she kept the clothes and things she gave away in the basement. She was always collecting every kind of thing and sending it here. Sometimes a wagon would drive up and unload.”[86]

Reviewing the record, one has to conclude that Mrs. Foster was blessed with a rare and special persona, a character and temperament that fitted her well for her occupation and the challenges it presented. Supported by her religious faith, she was able to resist despair in the face of the harsh deprivation she saw, the resistance or dishonesty of convinced and recalcitrant criminals she encountered, and the severity of the difficulties she ran up against every day, and to remain warm and sympathetic. And, remarkably, even cheerful, as was confirmed by one of her daughters, who, when asked whether Mrs. Foster’s work made her unhappy, described her as “the merriest one of the family. She seemed younger than her daughters.”[87] And yet she was practical and level-headed and of sound judgment at the same time, which qualities, as Judge Jerome noted, were critical to her ability to achieve her objectives. She was as far as it was possible to be from a well-meaning, but naive charitable dilettante.

Mrs. Foster was described as “a bright woman and brave as a lion. Her own deep troubles roused her sympathy for the desolate.” She was blessed with courage that was “prompt and unflinching.”[88] Chaplain Munro of the Tombs Prison called her “a woman of much ability and considerable force of character. She was … generous to a fault, and ready to help everyone in time of need …”[89] Judge Jerome spoke of her as “a small, nice-looking woman, very quiet and unobtrusive. And yet that is hardly right, either, for she was very active and always busy. But she went about her affairs in a direct and simple way.”[90] A coroner who encountered her often during his career wrote that “only a woman of her broad culture, large tolerance, and unprejudiced mind could exercise such influence as she exercised on Judges, juries, lawyers, and all who met her.”[91]

The Sheriff of the Tombs, who saw her almost daily and therefore knew her very well, said of her:

She was always bright and cheery, and had a laugh or a joke or a pleasant word for everyone. She used to come whisking in every morning, and trip through the place, saying good-morning to everyone by name. She always came bustling into my office as breezy and chipper as a young girl. It was always “Good morning to you, Sheriff; are you good-natured to-day?” You couldn’t help warming up to her … Every morning it was just the same. “I’ve got some people to see,” she would say. “Can I go into the cells?” She’d always ask. She could have gone right in, coming for… years that way, and everybody knowing her, but she always asked, and when I said, “Why, of course you can,” she’d say, “Thank you kindly, Sheriff; thank you kindly.” [92]

One of the judges commented on the strength of her character:

She was in no sense what is ordinarily termed a “strong minded woman.” On the contrary, in bearing and conversation she was as gentle as a child. In another sense, however, she was the strongest minded woman I ever knew in the persistence with which she carried out her projects. Her social and philanthropic lives were distinct. Socially she was genial, a fine conversationalist, and delightful. In her work she showed great sagacity in judging of the real character of a case, and never became so interested as to be sentimental.[93]

A reporter who had spoken to prison officials about her wrote these words in 1891:

Go into any prison or police court you choose in this city … and ask any official what he thinks of Mrs. Foster, and he will reply earnestly in words of almost extravagant praise. It is really very surprising how powerfully she has impressed them all with a sense of her goodness. Jailers who look upon the most pitiful scenes daily with supreme indifference, and from much practice talk habitually in hard authoritative tones, soften their voices perceptibly when speaking of her. [94]

One of those jaded and cynical jailers expressed his admiration in these striking words:

It’s perfectly amazing what power to comfort that woman has. I’ve had poor creatures here who would howl and screech and swear and shriek in rage by the hour, in spite of everything we and the matron could do and say. And then Mrs. Foster would come and just sit down outside the bars, and in five minutes them she-devils would be on the floor inside holding her hand through the bars and crying fit to shake their heads off, but quiet and subdued-like, you know.

And she don’t say much either. That’s what beats me out. But, then, maybe, you’d understand how she does it if you’d just talk to her once. She’s that gentle and sweet, and yet strong, you know, that – well, you know what I mean.[95]

Although Mrs. Foster clearly felt great sympathy for the defendants with whom she dealt and was willing to go to extraordinary lengths to help them, she could not have been as useful and effective as she was had she not been, at the same time, as alluded to in a quotation from Judge Jerome above, free from naiveté and impervious to ready deception from the promises and excuses given to her by unworthy potential recipients of her aid whom she encountered from day to day. The Sheriff of the Tombs said that “[y]ou couldn’t fool Mrs. Foster.” Sometimes she would be approached outside the Tombs by ex-prisoners, people in trouble, and “dead beats,” in the Sheriff’s words, who were looking to her for a “stake.” She would give them something, but she would not be misled by false promises of reform. Of the deadbeats, the Sheriff said, “[s]he was on to ‘em all right. She never talked reform to them.” She was, to be sure, “tender-hearted,” he said, “but not soft like some.”[96] Similarly, Judge Jerome observed that in her work she was often told untruths, “but her judgment was so good, and her experience so great, that it was the very rarest thing for any of these people to be able to deceive her.” When attempts to mislead her were made, he continued, “she was sagacious enough to detect the fact that they were untruths, so that when she reported to the court, the court felt that, as far as it was possible to ascertain them, all the facts of the case had been learned, and that it might act with perfect safety upon her report …” [97] When the facts warranted it, she would inform the court that, in her judgment, a defendant “was of such a character that she did not think there should be a suspension of sentence.”[98]

Mrs. Foster was “a woman of medium height, rather slender, with an exceedingly sweet face, topped with a wealth of black hair.”[99] The sexton at Calvary said that “to look at her, you would say she was no more than thirty-eight or nine, but she must have been over fifty.”[100] As was noted earlier, she always dressed the same in memory of the loss she had suffered when her husband had abandoned the family:

For years she has worn precisely the same sort of costume, and once you have seen her, whether you came on her suddenly, see her approaching in the distance, or only get a glimpse of her as she flits by, you will recognize her. She always wears a black dress and a widow’s hat with the crape veil behind, and not the slightest ornament to relieve the somberness of her costume. The nearest approach to color in her attire is the line of white ruffling around the inside edge of her hat, and that is scarcely visible unless you happen to be standing very near her. She is an indefatigable worker, and the respect in which she is held in the courts, prisons, and hospitals of the city is most marked. The moment she enters a court room every attendant will edge up a bit to see if there isn’t something he can do for her. City Magistrates and even the Judges of the Court of General Sessions will stop important cases to give Mrs. Foster an interview. Any request within reason that she may make is sure to be granted… [101]

Societies are obviously very complex mechanisms and are never wholly one thing. Still, scholars and writers tell us that life among the fortunate and the strivers of the last decades of the 19th century in New York City and in the United States in general was marked by conspicuous interest in and even preoccupation with wealth, gain, and social position and standing, as well as, with some frequency, propensity for corruption. Mrs. Foster lived in but also apart from this world: her personal circumstances, it appears, were comfortable, but her heart, her head, and the life of work she created for herself were very far removed from the world of those years as described by Mark Twain and from the social milieu referred to by Edith Wharton, with irony, as that of an age of innocence.

Table of Contents

A. Introduction

B. The Life and Work of Rebecca Salome Foster

- The Backgrounds of Rebecca and John A. Foster

- New York City in the Late 19th Century

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Began

- What Mrs. Foster Did for Prisoners, Their Families, the Courts, and Others

- Mrs. Foster’s Work in Her Own Words

- Funding the Work

- Providing Legal Assistance

- Traveling Throughout the City and Elsewhere

- The Tombs and “Five Points”

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Came to an End

D. What Happened to the Memorial

E. The Foster Family and a Home for the Marble Relief

G. Endnotes