B. The Life and Work of Rebecca Salome Foster

10. How Mrs. Foster’s Work Came to an End

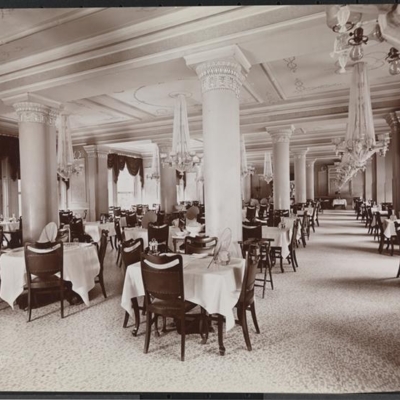

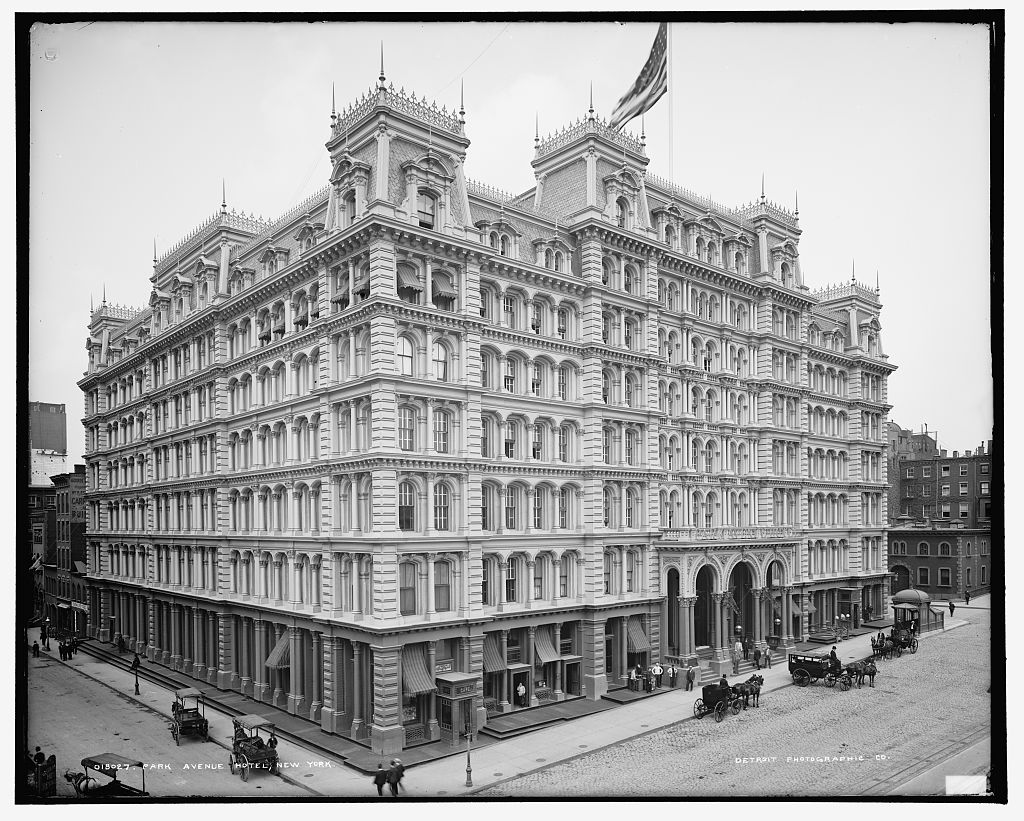

At age 54, Mrs. Foster was in full stride pursuing her work when she died, suddenly and tragically, on February 22, 1902, in a hotel fire that damaged a portion of the Park Avenue Hotel on the southwest corner of Park Avenue South and 34th Street. At one time she reportedly had lived at 441 Park Avenue at 30th Street, and the understanding of the Foster family has been that she had lived at addresses on East 76th and East 78th Streets in earlier years,[191] but in more recent times she had moved to the comfortable hotel, perhaps as a way to simplify her life after her daughters married. About 460 guests were in the hotel at the time of the conflagration. Seventeen persons, including Mrs. Foster, died in that fire. Two of the other victims were also members of the congregation of Calvary Church.

Fire, of course, was a great danger in New York City in those days given its many wooden structures. The Park Avenue Hotel, however, was large and modern (1878), with spacious quarters and accommodations for residents and guests, and was considered to be an advanced fireproof building. The fire appears to have been started by the transfer of burning embers from a fire that was in progress across Park Avenue South where the Seventy-First Regimental Armory was then located. The fire apparently raced up an elevator shaft in the hotel and many patrons trying to escape by stairway were overcome by smoke that engulfed that stairway. It was reported that Mrs. Foster, after having escaped from her room, Room 612, had returned to assist an elderly hotel patron:

[W]hen the fire started in the hotel, in which she lived, Mrs. Foster easily reached a place of safety. She was anxious about an invalid woman who was on one of the upper floors, and made repeated inquiries as to her safety. Lewis Edwards, who was in the hotel, said today that Mrs. Foster, on learning that the ill woman had not been accounted for, went back into the burning hotel and perished in her efforts to find the invalid, whom she sought to bring to a place of safety.[192]

Mrs. Foster’s untimely and sudden death came as a very great shock to many and, despite her aversion to publicity, was much reported on by the papers. Especially shocked and saddened by her death were the members of the local legal community — Judges, prosecutors, attorneys, and prison wardens and officers — and, of course, most poignantly, the prisoners and countless other unfortunates who had been the direct beneficiaries of her labors.

On February 23, 1902, the day before the funeral at Calvary Church, services were held in memory of Mrs. Foster at the Tombs, first in the women’s ward and later in the men’s ward.[193] “When it became known in the Tombs Prison that the ‘Tombs Angel’ had passed away there were some of the deepest expressions of grief that have ever invaded the walls of that forbidding structure.”[194] A service in her memory was held at God’s Providence Mission. It was reported that “Florence Burns … sorely misses Mrs. Foster. The latter, until her untimely death, daily visited Miss Burns and steadily encouraged her. The prisoner was visibly affected at both services in the women’s ward” in the Tombs.[195]

The day of Mrs. Foster’s funeral began with a simple service at the house of Mrs. William C. Bowers, Mrs. Foster’s daughter Jeanette. She and Mrs. Foster’s other daughter, Mrs. Francis S. Colt, and their three little children were the chief mourners, along with three of Mrs. Foster’s sisters.[196]

The opening of the courts that day was postponed to allow Judges and court staff to attend the funeral.[197] The funeral service was “[p]robably one of the most remarkable gatherings that was ever collected in a church of this city …”[198] “No woman has been laid away with more loving hands and more widely expressed sorrow than Mrs. Rebecca Salome Foster, ‘The Angel of the Tombs.’ The funeral was a sight such as is seldom seen in Greater New York.”[199] Those present included the District Attorney, many judges, and many attorneys, prosecutors, and prison staff, and those who had been helped by her. Indeed, said one press account, “[a]lmost in the same pews with the Judges who dispense the criminal laws in our courts sat men and women who had been reclaimed from lives of crime by the one to whose memory they had come to offer silent tribute.”[200] This account went on:

Prominent philanthropists and clergymen noted for their energy in many fields of charitable work mingled with turnkeys of the city prisons and attendants of the criminal courts. Children and young girls from the slums … mingled with men and women prominent in social life who had given generous financial aid to Mrs. Foster in her charitable work. Hundreds stood at the rear of the church and in the side aisles.[201]

Approximately 100 of the students from Mrs. Foster’s sewing school were there,[202] as were numerous Episcopal officials and representatives of the Society for the Protection of Jewish Prisoners.[203] Floral tributes were sent by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and the judges of the Supreme Court.[204] Throughout the service many women were noticed weeping silently in the rear of the church. Among those was Maria Barbella.[205] She brought flowers as a tribute to “my friend.”[206] Florence Burns sent flowers, as did jointly prisoners from the Tombs.[207]

Peter Seaman, who had been a court officer in General Sessions for almost thirty years, and who, with a score or more other attendants of the Criminal Courts, was in the church, said after the services that he had recognized at least 100 men and women there who had been arraigned before the criminal bar for various crimes, ranging from murder to petty larceny. [208]

Another account also noted the heterogeneity of the mourners:

A common sorrow called together a throng of people of all nationalities and social classes yesterday morning, and men of affairs, women of position and outcasts of the street wept together by the bier of their friend, Mrs. Rebecca Salome Foster …

The big auditorium was filled to the doors, while outside on the sidewalk a sad-faced group of unfortunates, too unfamiliar with churches and their ways to enter, paid their tribute of love in silent tears.[209]

After the funeral Mrs. Foster was buried alongside her husband and her children, Lomie and John, in the family plot in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

The day before the fire, Mrs. Foster had been making her usual rounds and had come into contact with two women who had been picked up in the streets. She had taken them to lodgings in St. Barnabas House to provide them with shelter. She had asked that shoes be given to the women, and had said that she would pay for them the next day. She did not live to fulfill her promise, but her request was considered her dying wish and the women received the best shoes to be found in the place.[210]

The Annual Report of the Prison Association of New York issued after Mrs. Foster’s death noted that “the impression which her earnest, intelligent and self-sacrificing work for prisoners had made upon the court is seen in the remarkable tribute which was paid to her in the Court of Special Sessions, which on motion of the District Attorney, adjourned in respect to her memory.”[211] In making this motion, District Attorney Jerome said:

What she was to this court and the unfortunate people with whom it has had to deal is too well known to need statement. For many years she came and went among us with but a single purpose: “That men might rise on the stepping-stones of their dead selves to higher things.”

There is a word which is seldom used. To us, who in administration of the criminal law are daily brought into contact with the misfortune and sin of humanity, it seems almost a lost word. It is the word “holy.” In all that word means to English-speaking peoples, it seems to me it could be applied to her. She was indeed a “holy woman.” It hardly becomes us to do aught else than to testify in holy, reverent silence of our love and respect. [212]

Presiding Justice Holbrook, in granting the motion, said:

It is eminently proper that we should interrupt our regular proceeding and pause for a moment to plant a flower of remembrance evincing our regard for that noble and saintly woman — Mrs. Foster — not inaptly called and known as “The Tombs Angel” — whose tragic and pathetic death has so greatly saddened our hearts. Mrs. Foster was known to and highly respected by all who frequent this court. Perhaps none knew her better than the members of this bench, on whom she was wont to call almost daily in the performance of her benevolent work, and in the discharge of her duties as a probationary officer of this court.

It has been very truly and eloquently said of Mrs. Foster by the learned District Attorney, that to those in distress, and especially to those of her own sex, she was a good and true angel. To the erring and wayward, her large, generous, and womanly heart ever went out with sincere and deep sympathy. Her appearance at the dark and gloomy cell to the inmates was like a veritable sunbeam. Numberless lonely and weary hearts have been cheered, gladdened, and made even radiant by her ministrations and words of good cheer, and numberless, too, of those who have strayed from the straight and narrow way were brought back by her sweet influence to paths of rectitude and virtue. …

We shall all miss her bright, charming face, and many, very many, alas! will miss her cheerful words of comfort and hope. As a slight token of our esteem, and as a perpetual reminder of her good works, the clerks will cause these proceedings to be entered upon the minutes of this court.[213]

The Court of General Sessions and the Supreme Court also adjourned in her honor.[214]

Mrs. Foster was eulogized by the Rector of Grace Church in these words:

“The Angel of the Tombs” men called her. A strange epithet, and to one who knew nothing of our city’s ways and woes an unintelligible one; but what it meant our Judges know, our prosecuting attorneys know, yes, best of all, those poor creatures know by whose suffrage this unique order of merit was created and conferred. It was they who named her “Angel,” they whose dwelling place was the Tombs, and into whose dark lives she came as a messenger of light. [215]

A newspaper report days after her funeral gave an indication in concrete terms of the extent of the gap left by her death:

With the death of Mrs. Rebecca Salome Foster, the “Tombs Angel,” the work of the committee known as the Friends at Court is at an end, and the organization will disband. The balance in the treasury, which amounts to about $1,300, will be returned to the subscribers, or, if they agree, will be used to continue some project dear to Mrs. Foster’s heart at the time of her death, and so serve as a memorial of her useful life. Whether it will be employed to help one life or to extend some more general work is not yet decided. [216]

In 1909, Commodore Elbridge T. Gerry, who was at various times the president of and counsel to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, testified before a legislative commission examining the lower courts of the city. He took the occasion to describe Mrs. Foster as the most efficient “probation officer” the city had ever seen, a born friend of children and those in need of sympathy. [217]

In the year of her death, a tablet in Mrs. Foster’s memory was unveiled in God’s Providence Mission on Broome Street, where she had run her sewing school for many years.[218]

The Warden of the Tombs, reflecting after her death, said that he had never in his life seen another woman like Mrs. Foster and never expected to. “She was the kindliest, the gentlest woman in the world …”[219]

Nobody can ever know the amount of good that woman did in the many years she worked in this prison.

She had a genius for the work. She could talk five minutes with a prisoner and entirely win her confidence … Hundreds, perhaps thousands of first offenders were saved by her from adopting a criminal career. [220]

Table of Contents

A. Introduction

B. The Life and Work of Rebecca Salome Foster

- The Backgrounds of Rebecca and John A. Foster

- New York City in the Late 19th Century

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Began

- What Mrs. Foster Did for Prisoners, Their Families, the Courts, and Others

- Mrs. Foster’s Work in Her Own Words

- Funding the Work

- Providing Legal Assistance

- Traveling Throughout the City and Elsewhere

- The Tombs and “Five Points”

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Came to an End

D. What Happened to the Memorial

E. The Foster Family and a Home for the Marble Relief

G. Endnotes