This biography was prepared in 2012 and does not include Judge Lippman’s final years as Chief Judge or his life after leaving the bench. In 2018, the Society collected his oral history. For more information on Judge Lippman’s life after the Court of Appeals, view his Oral History.

In New York, for well more than a decade, we have taken the view that the court system has a unique role in informing public policy as it relates to the administration of justice. … [T]he courts have become the emergency room for society’s worst ailments — substance abuse, family violence, mental illness, mortgage foreclosures, and so many more — all of which are so much a part of the court dockets we face today. And if we are to fulfill our constitutional mission in the face of these plagues of modern-day life, if we are to remain relevant and responsive to the public’s needs and expectations, we have to engage our changing caseloads and the societal problems they reflect, including the complex policy issues and nontraditional challenges they present for us as judges, court leaders and administrators.

— Remarks before the California Judicial Council Forum on State Court Leadership on Public Policy Issues, June 26, 2008.

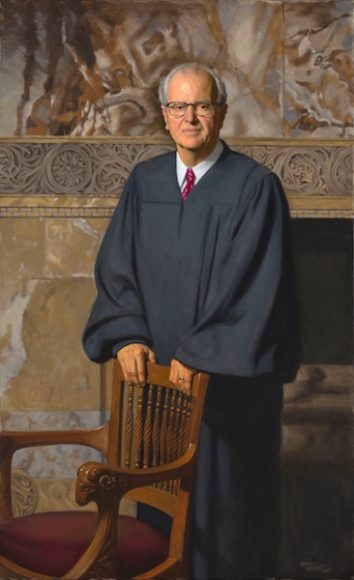

While the appointment of any new judge, and especially a new chief judge, is a landmark event at the Court of Appeals, Jonathan Lippman’s appointment as Chief Judge of New York in February 2009 was particularly auspicious. It marked a significant moment in the Court’s jurisprudential history: though widely recognized as a consensus-builder, the new chief judge would alter the Court’s rhetorical style, spur greater public discussion of divided issues and more frequent dissent, and contribute a voice of pragmatic progressivism to the Court’s exceptional bench, leading to national precedents on issues such as search and seizure, right to counsel, and executive government. It marked an equally important moment in court administration: with Lippman’s elevation, the Judiciary would be led for the first time by a jurist who had spent his entire career rising within its ranks; one who brought intimate knowledge of its key personnel, its extensive operations in hundreds of facilities around the State, its complex budget, and the array of operational rules and practices of its fourteen separate trial and appellate courts; one equally versed in the political process that governed court finance and the media relations critical to its public image. Through this experience, Lippman brought a finely honed vision of the administrative court system as a political institution — as a creative and independent branch of government, responsible not only for resolving cases, but also for addressing the societal problems embodied in its dockets and protecting and extending the most fundamental rights of access to justice, broadly understood.

The fruits of Lippman’s leadership, begun during his twelve years of service as Chief Administrative Judge alongside Chief Judge Judith Kaye, have been broadened since 2009 in a raft of initiatives: a permanent commission on sentencing, task forces on civil legal services and wrongful convictions, caseload limits for providers of indigent legal services to criminal defendants, administrative reassignment of cases involving campaign contributors to judges, a pro bono requirement for attorney admission to the bar, numerous initiatives in residential foreclosure practice, innovative funding of criminal and civil legal services (including funding through the judicial branch), permanent resolution of the longstanding problem of judicial salaries, and many others. Viewed singly, these qualities place Lippman in the upper ranks of judges in the Court’s distinguished history. Viewed together, they place him in the elite company of its finest jurists.

Beginnings (1945-1972)

Jonathan Lippman was born on May 19, 1945 in New York City, the third of four children of Ralph and Evelyn Lippman. His grandparents, descendants of Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews, immigrated to the Lower East Side of Manhattan from western Belarus and Galicia in the late 19th century, part of the massive migration of east European Jews to the United States between the assassination of Alexander II and the start of World War I.1 Like many in this movement, his forebears settled as small shopkeepers — one grandfather was a butcher, the other a presser — prizing highly for their children the education that had been unavailable to them in Russia and Poland. Ralph graduated from New York University in 1934, Evelyn from Hunter College one year later.2 The couple married in 1938, and moved in 1943 to Amalgamated Dwelling, part of a housing complex sponsored by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union on the Lower East Side. Early in his professional life, Ralph Lippman operated a highly successful poultry business. But he was drawn to another calling: in 1954, at considerable sacrifice in income, he took a management position at the complex, then known as Cooperative Village. Several years later, he became its president and general manager.

Cooperative Village was no ordinary living space; and Ralph Lippman was no ordinary building manager. Comprising more than 4400 apartments in four major projects, designed by architect Herman Jessor and constructed between 1930 and 1960 along Grand Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the cooperatives were intended as affordable housing for the working class, and were modeled after Sidney Hillman and Abraham Kazan’s Amalgamated Housing Cooperative in the Bronx.3 Operated under the Rochdale Principles and set in space cleared from surrounding tenements, they were designed to provide residents with parks, shops, common rooms, playing fields, and other social amenities — as well as opportunities for education and cultural enrichment. At their peak, the cooperatives included a central power plant, shopping center, and auditorium, and housed more than ten thousand tenants. As manager of this development, the elder Lippman was responsible for every aspect of life in the community — tenant matters, building maintenance, governance issues, relations with unions and local political officials, and countless others. A great admirer of Kazan’s work, he performed this role — which required passionate commitment, knew no fixed hours, and combined politics, engineering, education, social services, finance, and philosophy — exceptionally for more than thirty years. As the Chief Judge later affectionately recalled, his father was so devoted to representing the interests of the 10,000 tenants, and so effective at dealing with City officials, that he came to be known as the “Mayor of Grand Street.”4 Throughout this period, Ralph Lippman was a powerful moral compass within his family and his community — highly idealistic, intensely practical, and possessed of a herculean work ethic.5 It was perhaps inevitable that the passion, commitment, and work ethos of the father would pass by example to the son. From an early age, Jonathan displayed a curiosity about the problems and potential of civic institutions; the wall of his room bore a picture of John F. Kennedy; later he was privileged to know and admire a cadre of distinguished judges in the New York courts — Sam Spiegel, Jack Markowitz, Xavier Riccobono, Betty Ellerin, Leo Milonas, Judith Kaye. But Lippman’s greatest hero was, and remained, his father.

In the setting of Cooperative Village, the Lippman children enjoyed the blessings of a warm, close knit household, linked to a wide urban community of family and friends. The future judge grew up playing basketball, stoopball, and baseball; he became a devoted fan of the New York Yankees and the New York Knicks; together with his brothers, he spent summers at the idyllic rural retreat of Camps Oxford/Guilford in Chenango County, New York.6

Like their parents, Ralph and Evelyn Lippman were unsparing in their devotion to their children’s education.7 Young Lippman was an exceedingly diligent student, and excelled in academics. Following graduation from Stuyvesant High School shortly after his sixteenth birthday, he earned a B.A. in 1965 from New York University, cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, majoring in political science and international relations. He initially planned to pursue a professorial career. But at the urging of his father, he instead attended law school at New York University, where he received his JD in 1968. Following a period of service as a social studies teacher in the New York City School system — and after flirting with an offer to practice labor law — Lippman joined the Unified Court System as a law assistant in early 1972. As he later described it, with typical self-deprecation: “I showed up on the last day that funding for the position was set to expire, so they hired me. I was just at the right place at the right time.”8

Early Legal Career (1972-1989)

The court system that Lippman joined in 1972 was a system in transition.9 The economic boom in the years following the Second World War, including significant population growth, an explosion in production of automobiles and other consumer goods, massive public and private expenditure on housing, highways and public works, expanded educational opportunities, and increasing use of the courts to review public policy issues resulted in what some commentators have described as a “mid-century law explosion” in New York, and stirred calls for court reform. In response, New York amended its Constitution and Judiciary Law in 1961 to end the localized manner in which the courts had long been organized and governed — establishing the court structure that remains in effect today; consolidating administrative decision-making; and creating, at least in name, a “Unified Court System.” In 1976, the Unified Court Budget Act established centralized State funding for major courts, and gave the Judiciary stronger control over its budget. In 1977, a further constitutional amendment created a system of court management under the leadership of the Chief Judge, acting in conjunction with the Presiding Justices of the Appellate Division, implemented through a Chief Administrator, pursuant to statewide policies approved by the Court of Appeals. In the years that followed, these changes brought unprecedented reform to New York’s trial court administration in numerous areas: labor and civil service practices, court construction and maintenance, assignment and reassignment of judges, calendaring practices, security, judicial education, courtroom access, jury reform, records maintenance, and many others. They created a streamlined and uniform process for detailed rule-making for courts around the State, and permitted wiser allocation of court resources. They strengthened the role of the judiciary in Albany in both budget and legislative matters. Above all, they gave the court system the power and flexibility to address court-related problems anywhere in the State in a timely, efficient, and increasingly creative manner.

This administrative revolution was still in its early stage, its full implications yet unconceived, when Lippman joined the legal staff of the New York County Supreme Court at 60 Centre Street in Foley Square in January 1972. In those years, his efforts were the prosaic exercise of many young lawyers and clerks — reviewing endless motions, researching issues of law, drafting memoranda and decisions. As he recalled more than three decades later:

I started out working as an entry-level court attorney writing memos and drafting decisions for the Justices of the Supreme Court in New York City. To this day, I remember them all, each and every one of them, as giants in their own right, lawyers of every stripe and background, a real melting pot of New York City, who had worked themselves up, generally from humble beginnings, to be Supreme Court Justices — and how in awe I was! At 60 Centre Street, I had the opportunity to work in every nook and cranny of the court and became fascinated with how the court system worked and, in some circumstances, how it failed to work. I came to love the multilayered nuanced world of the judicial system, with its amazing constellation of different categories of people and different constituencies — judges, trial lawyers, commercial lawyers, litigants, jurors, representatives from law enforcement and the other branches of government, our own internal employee groups and organizations, the press, the bail bondsmen, assorted hangers-on — even in those days there were court “groupies” — and most important of all, the public that we serve, thousands of them, streaming in and out of the courthouse every day. At that time, there were no magnetometers, no lines — this was truly the people’s courthouse.10

Two years later, he joined the staff of the Hon. Samuel Spiegel, his earliest judicial mentor, from whom — first in Supreme, later in Surrogate’s Court — he learned the nuances of trial court and chambers operation. Upon Spiegel’s untimely death in 1977, Lippman returned to 60 Centre Street as deputy chief court attorney; six years later, he was elevated to Chief Clerk and Executive Officer of New York County Supreme Court, responsible for all aspects of court operations; in 1989, with the approval of Chief Judge Sol Wachtler, he was appointed by Chief Administrator Matthew Crosson as UCS Deputy Chief Administrator for Management Support.

Character and Qualities

Lippman later described the latter appointment, and his general rise through the court hierarchy, as serendipity and fortunate timing.11 But that explanation is not borne out by the historical record. As numerous colleagues and supervisors would later attest, the appointment and those that followed were based on an early appreciation by senior judges or administrators — Spiegel, Edward R. Dudley, Riccobono, Crosson, Ellerin, Wachtler, Bellacosa, and later Milonas and Judith Kaye — of several extraordinary qualities of mind and habit.

Foremost was a superlative intelligence, interest, and detailed knowledge of the court system. In his years at 60 Centre Street, and even more effectively in the years that followed, Lippman developed an almost encyclopedic command of court operations and personnel. The Manhattan Supreme Court venue was (and remains) the busiest courthouse in the State. Issues of building management, staff and human resources, court calendaring, records management, security, press — every facet and challenge of court operations crossed Lippman’s desk during his tenure as executive officer.12

Blended with this intelligence and empirical memory was an extraordinary work ethic — an unparalleled persistence in getting results. Years later, Chief Judge Kaye would recall one occasion when Lippman worked so late into the night on a pressing project that, shortly after leaving the office, he suddenly could not remember if he was on his way home after a long day or on his way back to work after a brief respite at home.13 That habit was by then longstanding: he would typically rise before dawn, appear in the office by 6:30, and work steadily until late evening.14 Colleagues grew accustomed to early calls and late messages. In a culture where hard work was commonplace, Lippman was exceptionally committed. And as early as the mid-1980’s, when he spearheaded the conversion of the Civil Branch at 60 Centre Street to an individual assignment system, he demonstrated his ability to apply that energy to lead major court projects.

Yet this work ethic did not come at cost of personal engagement with colleagues and staff. Lippman possessed social instincts to a degree quite rare in those outside elective office. His was an effortless collegiality, a highly-tuned capacity to see issues from others’ perspective and to convey empathy — and a remarkable ability to marshal this understanding into persuasive power.15 It was a skill that would be applied with good effect on countless occasions — at judicial budget hearings; in intense labor negotiations; in presentations of programs to the Administrative Board; in thousands of quiet conversations and telephone calls pressing programs and projects past objections.16 This capacity brought a collateral benefit: an ability to judge character, to size people up, to assess their inclinations, motivations and abilities — qualities crucial to Lippman’s effectiveness as an administrator and judge.

Finally, even at this early stage in his career, Lippman brought to his duties an irrepressible and infectious optimism and nascent vision — a belief that no matter how difficult and intractable a current problem might appear, it could be solved through intelligent effort and diligent application. This belief was an invitation to others to suspend skepticism, tolerate compromise, and embrace innovation — an important component of his ability to inspire and lead.17

Deputy Chief Administrator (1989-1995)

The June 12, 1989 meeting of the Administrative Board of the Courts, at which Chief Judge Wachtler introduced the new deputy chief administrator, was the first of more than two hundred Board meetings which Lippman would attend and ultimately direct in the decades that followed. The discussions at that meeting, reflected in its minutes, evidence the rich scope of his new duties: certification of several judges for service as retired justices of the Supreme Court; ethical constraints upon judicial hearing officers; proposed sanctions for attorney failure to attend a scheduled appearance in Family Court; continuing legal education for attorneys; proposals for judicial education and evaluation of judges; the application of the ADEA to the judiciary; court construction and the Court Facilities Capital Review Board; cameras in the courts; per diem expenses for reassigned city, town and village judges and justices; provision of law guardian services in Family Court; staffing issues; proposed amendments to fee provisions of the CPLR; rules for handling attorney trust accounts; and changes in rules of attorney professional responsibility.

In the years that followed, the list of items on the Board’s meeting agenda grew longer and ever more diverse. Working through these and other operational demands alongside several chief administrators — Judge Rosenblatt and Matthew Crosson (under Chief Judge Wachtler), and Judge E. Leo Milonas (under Chief Judge Kaye) — Lippman developed a nuanced understanding of every major aspect of court operations in more than 300 locations around the State, every principal detail of the courts’ billion-dollar budget, and every major decisionmaker, both within the courts and outside it, that influenced its well-being and direction. In 1995, Governor Pataki named him to the Court of Claims. Upon Judge Milonas’ return to the Appellate Division at the start of 1996, Chief Judge Kaye elevated Lippman to Chief Administrative Judge — the eighth since the constitutional amendment of 1977.18

Chief Administrative Judge – The Grand Partnership (1996-2007)

The duties of the Chief Administrator of the Courts are daunting: senior executive officer, chief legislative lobbyist, principal budget strategist, master builder — as well as the senior counselor and confidante of the Chief Judge — among many more. The role requires a rare combination of diplomatic, tactical, and legislative skills, as well as a deep understanding of legal principles, court practices, and the culture of judges. Prior to Lippman’s appointment, average tenure in the position was three and one half years; in an astonishingly fruitful partnership with Chief Judge Kaye, Lippman would hold it for more than eleven.

The extraordinary achievements of that partnership have been discussed at length elsewhere in this volume.19 They included implementation of jury reform; establishment of problem-solving courts; innovative and dramatic improvements in case management; reformation of matrimonial court practices; mandatory continuing legal education and mandatory fee arbitration for attorneys; creation of the Commercial Division of the Supreme Court; enhanced access of press and public to court facilities; expansive use of the internet for internal court operations and public access to UCS resources; creation of the Judicial Campaign Ethics Center and other judicial campaign ethics reforms; extensive revision of court rules relating to the judicial appointment of fiduciaries; and comprehensive modernization and professionalization of the State’s 1300 town and village courts. In his capacity as chair of the State’s Facilities Capital Review Board, Lippman oversaw the construction of major courthouses in Brooklyn and the Bronx, and the expenditure of more than $2.5 billion in construction projects around the State. He administered the creation of New York’s Judicial Institute, the only court system year-round educational and training facility for judges in the nation. He oversaw an explosive expansion of technology in the courts — including CourtNet, a high-speed fiber optic intranet network connecting every judge and judicial employee in the State; internet-based case tracking and calendaring systems, the development of a statewide centralized automated case processing system, enhanced use of videoconferencing for inmate and witness appearances, posting of court decisions online, expanded data-sharing with justice agencies around the state, and an internet-based system for filing and serving court documents (“e-filing”). He pressed for the expansion of access to justice initiatives, including greater funding for civil legal services and resources for self-represented litigants.20 Finally, he greatly strengthened the court systems ties with bar associations, advocacy and good government groups — the New York State Bar Association, the City Bar, the New York County Lawyers, the Fund for Modern Courts, the National Center for State Courts, the National Organization of State Court Administrators, and numerous others.21 In Lippman, these groups found a court insider whose interest in policy issues and practical proposals for court reform matched their own; over time, these groups would serve as think tanks and valuable legislative allies to the court system.

Each of these initiatives was a noteworthy achievement; together, they represent an exceedingly productive period in the history of the New York court system, made possible by the unique partnership between Judge Kaye and Judge Lippman. As Lippman noted in a 2000 interview, the two were driven by a desire to alter the court system fundamentally, albeit incrementally: “We don’t want to just survive,” Judge Lippman said. “We want to change the system in a real way, not by fiat but by laying the foundation for a different court system. We are not content to let events run us. We don’t intend to be anybody’s victim. Rather we intend to proactively promote change in a studied, incremental way. I truly believe the face of the court system has changed dramatically over the years. We are very proud of that, and just as proud of the way it has been done …”.22

Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division (2007-2009)

In 2005, Lippman was elected as a Justice of the Supreme Court for the Ninth Judicial District — his first and only elective office; he was thereafter appointed as an Associate Justice of the Appellate Term, Ninth and Tenth Judicial Districts. In May 2007, he was appointed by Governor Eliot Spitzer to succeed John Buckley as Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, First Department.

Housed in a spectacular palladian courthouse on Madison Avenue and E. 25th Street, the Appellate Division, First Department has held sway over state court appellate matters arising in Manhattan and the Bronx since the turn of the twentieth century. Its annual docket of three thousand cases include complex commercial litigation and high-profile criminal matters of every description; its cadre of judges, sitting in panels of four or five, are highly experienced and independent jurists; and its practitioners rank among the most sophisticated lawyers in the nation. Leadership of this Court marked a sharp change in direction for Lippman in several respects. For the first time in decades, legal precedents replaced administrative projects as his principal tasks (although the Court, and especially its Presiding Justice, maintained a high degree of operational independence in the aftermath of administrative reorganization in the 1970s). For the first time, he heard and decided cases regularly, participating in over a thousand appeals and countless motions during his tenure. Like any appellate division judge, he was faced with constantly changing bench assignments, where the court’s perspectives on issues might vary subtly from day to day. Finally, the appointment marked his introduction to a style of court culture quite distant from the Chief Administrator’s office in downtown Manhattan, and presented him with the opportunity, for the first time, to demonstrate fully his skills at collegial leadership and management of a court in all its aspects. While Lippman had played a leading role in the evolution of the court system over two decades, only upon his appointment as Presiding Justice did commentators first speak of a “Lippman Court.”

That Court did not disappoint expectations. In his twenty-month tenure, Lippman strengthened the Court’s Law Department and eliminated a case backlog of several hundred decisions; revised procedures for drafting decisions, freeing chambers staff to concentrate on legal analysis of challenging cases; and instituted a system of special case conferencing to address thorny bench disputes. He instituted a broad review of court practices by the National Center for State Courts, to assess operational performance and need. He streamlined the Court’s attorney admissions process; introduced and expanded scanning and electronic publishing technologies by the Court, email communications, internal televised court proceedings, and internet-based resources; and established, by example rather than dictate, greater commitment to diversity at all levels within the Court. He restored a high level of morale and collegiality among judicial and non judicial staff. He mastered the vagaries of bench politics, and honed his skills at building majorities. He was a tireless advocate for the Court, both internally and in the legal community, and reestablished close ties with local bar associations. Above all, he brought energetic leadership and a willingness to experiment with new ideas and technologies while honoring the Court’s great traditions.

Appointment to the Court of Appeals (2009)

In January 2009, upon the retirement of Judith Kaye, Governor David Paterson appointed Lippman as Chief Judge of New York and Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals. One month later he was confirmed by the Senate; he sat for argument for the first time at Court of Appeals Hall on February 26, 2009. For Lippman, the daunting transition to the State’s highest judicial post was more akin to a happy reunion with old colleagues and friends: he had worked closely with many members of the Court — Senior Associate Judge Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick, Victoria A. Graffeo, Susan Philips Read, Robert S. Smith, Eugene F. Pigott, and Theodore T. Jones, Jr. — and his natural affability, humor, and empathy blended immediately and well with its traditional tight-knit collegial spirit.

As if to greet the new arrival fittingly, the docket of the Court contained an unusual number of high-profile matters, three of which resulted in majority opinions by the new chief judge in the months that followed. In People v. Weaver, 12 N.Y.3d 433 (2009), the Court declared unconstitutional the warrantless installation by police of a global positioning system device that permitting the tracking of a suspect’s vehicle at great distance for lengthy periods at minimal cost. In Skelos v. Paterson, 13 NY3d 141 (2009), his majority opinion confirmed the power of the Governor to fill the vacant office of Lieutenant Governor by appointment under Public Officers Law ’43 — ending an unusually fractious and deadlocked 2009 legislative season. In Goldstein v. New York State Urban Development Corp., 13 NY3d 511 (2009), the Court upheld New York City’s taking of private property in Brooklyn for the controversial Atlantic Yards development.

Hints of Lippman’s jurisprudential inclinations and his understanding of the role of the Court were present in these early writings. For example, the justifications proffered for GPS usage in Weaver — cost savings, tactical benefits, and serious new criminal threats faced by law enforcement authorities — seemed designed to appeal to a budget-conscious and technologically sophisticated jurist. Yet Lippman viewed precisely these features as a cause for judicial caution and skeptical reserve, and rejected arguments that regulation of such conduct was a legislative, rather than a judicial concern (12 NY3d 433, 446-447):

[…] [T]he gross intrusion at issue is not less cognizable as a search by reason of what the Legislature has or has not done to regulate technological surveillance. Nor does the bare preference for legislatively devised rules and remedies in this area constitute a ground for treating the facts at bar as of subconstitutional import. Before us is a defendant whose movements have, for no apparent reason, been tracked and recorded relentlessly for 65 days. It is quite clear that this would not and, indeed, realistically could not have been done without GPS and that this dragnet use of the technology at the sole discretion of law enforcement authorities to pry into the details of people’s daily lives is not consistent with the values at the core of our State Constitution’s prohibition against unreasonable searches.

* * *

Technological advances have produced many valuable tools for law enforcement and, as the years go by, the technology available to aid in the detection of criminal conduct will only become more and more sophisticated. Without judicial oversight, the use of these powerful devices presents a significant and, to our minds, unacceptable risk of abuse.23

In Goldstein, reaffirming the deference owed by courts to factual conclusions of administrative agencies acting within the scope of their legislatively granted powers, he declined to substitute a judicial view for the UDC’s findings of “blight” or determination of appropriate “public use” (13 NY3d at 526):

It is important to stress that lending precise content to these general terms has not been, and may not be, primarily a judicial exercise. Whether a matter should be the subject of a public undertaking — whether its pursuit will serve a public purpose or use — is ordinarily the province of the Legislature, not the Judiciary, and the actual specification of the uses identified by the Legislature as public has been largely left to quasi legislative administrative agencies. It is only where there is no room for reasonable difference of opinion as to whether an area is blighted, that judges may substitute their views as to the adequacy with which the public purpose of blight removal has been made out for those of the legislatively designated agencies; where, as here, “those bodies have made their finding, not corruptly or irrationally or baselessly, there is nothing for the courts to do about it, unless every act and decision of other departments of government is subject to revision by the courts” ( Kaskel [v. Impellitteri], 306 N.Y. at 78, 115 N.E.2d 659 [1953]).

Also apparent in this first year, and more so in those that followed, was a change in the Court’s philosophy of dissent. As many commentators noted, the number of dissents issued by the Court increased substantially during and after 2009. Weaver and Skelos were each decided by a 4-3 vote; the Chief Judge himself would author more than thirty-three dissents during his first forty months on the high court; other judges would follow suit. Whereas the Kaye Court had striven to speak in a single voice, the Lippman Court prized — together with collegiality, articulate draftsmanship, and intellectual rigor — the distillation of alternative views. The Chief Judge observed in a 2011 interview:

To me, it’s a common-sense Court. It is a court that is not predictable in any particular case. I think we often disagree, but are never disagreeable with one another. It is a Court that I don’t think is easy to label.24

Lippman’s Jurisprudence

It has been rightly observed that the application of critical labels to the work of a sitting member of the Court can be premature and perilous.25 Yet a handful of characteristics in Lippman’s work bear mention, even in its emergent state. These include, in no particular order: close attention to the policy purposes underlying both statutes and common law principles; distaste for legal fictions; keen practical analytic bent; skepticism toward government rationales of institutional convenience; nuanced understanding of the psychology of victims, investigators and witnesses; insistence on firm standards of review; disinclination to second-guess fact-finding by hearing officers or trial courts; and great sensitivity to the Court’s duty in assuring access to legal representation. Above all, Lippman’s approach to the law reflects a deep belief in the common law as an evolving jurisprudence — one that takes its life from application of old principles to new circumstances — and a strong conviction of the Court’s duty to address problems and find remedies. One or more of these themes may be found in most of the Chief Judge’s writings; a few examples, reflecting his limpid, elegant, and understated prose style, will suffice in illustration.

In Hurrell-Harring v. State, 15 N.Y.3d 8 (2010), Lippman penned a majority opinion finding that indigent defendants left unrepresented at arraignments by 18-B assigned counsel programs in several upstate counties could pursue collateral claims for denial of the basic right to counsel under Gideon v. Wainwright,26 noting (15 N.Y.3d at 26-27):

Assuming the allegations of the complaint to be true, there is considerable risk that indigent defendants are, with a fair degree of regularity, being denied constitutionally mandated counsel in the five subject counties. The severe imbalance in the adversary process that such a state of affairs would produce cannot be doubted. Nor can it be doubted that courts would in consequence of such imbalance become breeding grounds for unreliable judgments. Wrongful conviction, the ultimate sign of a criminal justice system’s breakdown and failure, has been documented in too many cases. Wrongful convictions, however, are not the only injustices that command our present concern. As plaintiffs rightly point out, the absence of representation at critical stages is capable of causing grave and irreparable injury to persons who will not be convicted. Gideon’s guarantee to the assistance of counsel does not turn upon a defendant’s guilt or innocence, and neither can the availability of a remedy for its denial.

In Hirchfeld v. Teller, 14 N.Y.3d 344, 354 (2010), Lippman argued in dissent that the Office of Mental Health lacked authority to limit, through licensure requirements, the availability of counsel (through Mental Hygiene Legal Services) to residents of certain OMH facilities:

It is not the role of health care administrators to determine when and where due process requires the presence and assistance of an attorney. That judgment is peculiarly within the competence and expertise of the judiciary. Thus, while it is undoubtedly highly and expressly relevant to the jurisdictional inquiry whether a place or facility is required to have an operating certificate pursuant to article 31 of the Mental Hygiene Law, that determination, for MHLS jurisdictional purposes, is not OMH’s to make. It is in this unique context, when disputed, properly made by the courts with the jurisdictional statute’s broad remedial purposes in mind.

In dissent in Matter of Jimmy D., 15 N.Y.3d 417, 425 (2010), Lippman argued that waiver of Miranda rights by a thirteen-year-old in the company of his mother did not permit police thereafter to extract a confession from the child, in his mother’s absence, through the deceptive promise of “help.” Such promises to a child of that age and stage of development, under typical conditions of extended interrogation, were an invitation to storytelling:

If an “incentive to lie” [citing the majority opinion] were necessary to explain a 13 year old’s decision to confess falsely, there certainly was one in this case; the child believed, as he had been encouraged to in his mother’s absence, that making the sought confession was the only way he could extricate himself from the extraordinarily aversive situation in which he found himself. Children do resort to falsehood to alleviate discomfort and satisfy the expectations of those in authority, and, in so doing, often neglect to consider the serious and lasting consequences of their election. There are developmental reasons for this behavior which we ignore at the peril of the truth seeking process.

In Bazakos v. Lewis, 12 N.Y.3d 631, 635 (2009), again in dissent, he argued that claims against a physician retained by a litigation adversary for an injury suffered in the course of a medical examination sounds in simple negligence, rather than malpractice: treatment of the examination as a traditional medical relationship was an unnecessary fiction leading to unjust results:

The duty here implicated does not arise from what is reasonably susceptible of characterization as a doctor patient relationship, i.e. a treatment relationship; it is simply an instance of the general obligation, frequently enforceable in tort, to refrain from causing foreseeable harm. That is ordinary negligence. It is today denominated “medical malpractice” only by dint of an exercise in judicial artifice untethered to any law or to the actual nature of the transaction known euphemistically as an “independent” medical examination. These exams, far from being independent in any ordinary sense of the word, are paid for and frequently controlled in their scope and conduct by legal adversaries of the examinee. They are emphatically not occasions for treatment, but are most often utilized to contest the examinee’s claimed injury and to dispute the need for any treatment at all. . . . The majority’s bare assertion that medical treatment is compatible with this context is merely a form of words.

In Runner v. New York Stock Exch., Inc., 13 N.Y.3d 599 (2009), writing for a unanimous Court in answer to a certified question from the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, Lippman found that Labor Law section 240(1) imposed liability for injury to a construction worker dragged into a makeshift pulley by a falling weight. In so doing, he applied a practical test to implement the policy purpose served by the statute, rejecting the defense argument that past precedent required narrower parsing:

Manifestly, the applicability of the statute in a falling object case such as the one before us does not under this essential formulation depend upon whether the object has hit the worker. The relevant inquiry, one which may be answered in the affirmative even in situations where the object does not fall on the worker, is rather whether the harm flows directly from the application of the force of gravity to the object. Here, as the District Court correctly found, the harm to plaintiff was the direct consequence of the application of the force of gravity to the reel. Indeed, the injury to plaintiff was every bit as direct a consequence of the descent of the reel as would have been an injury to a worker positioned in the descending reel’s path. The latter worker would certainly be entitled to recover under section 240 (1) and there appears no sensible basis to deny plaintiff the same legal recourse.

Writing for the majority in San Marco v. Village/Town of Mt. Kisco, 16 N.Y.3d 11 (2010), Lippman concluded that a statutory written notice requirement for suit against municipalities (including an exception for municipal acts that “immediately” produce a hazardous condition) did not shield a municipality from a claim for injury that was caused by the natural and foreseeable consequences of its own negligent maintenance practices — in that case, the removal of snow to a municipal parking lot. The public policy purposes served by the statute did not include protection of a village from responsibility for foreseeable harm caused by its own deliberate conduct:

Considering the present facts in light of the underlying purpose of prior written notice statutes, we find these statutes were never intended to and ought not exempt a municipality from liability as a matter of law where a municipality’s negligence in the maintenance of a municipally owned parking facility triggers the foreseeable development of black ice as soon as the temperature shifts. Unlike a pothole, which ordinarily is a product of wear and tear of traffic or long term melting and freezing on pavement that at one time was safe and served an important purpose, a pile of plowed snow in a parking lot is a cost saving, pragmatic solution to the problem of an accumulation of snow that presents the foreseeable, indeed known, risk of melting and refreezing.

[. . .] Thus, the determinative factor in this case should be whether the Village’s snow removal efforts created the ice condition on which San Marco fell.

In Sullivan v. Harnisch, 2012 WL 1580602 (2012) writing in dissent, Lippman argued that common law principles of at-will employment — including the Court’s holding in Wieder v. Skala (80 N.Y.2d 628 [1992]) — permitted a suit for wrongful discharge by a hedge fund compliance officer terminated to prevent investigation of a company official’s deceptive trade practices and violation of securities laws. To Lippman’s eye, the majority’s insistance upon a legislative solution to address such misconduct ignored the proper role of a common law court.

The Court’s decision concludes that “[n]othing in federal law persuades us that we should change our own law to create a remedy where Congress did not” [citation omitted]. The clear implication of this statement is that in order for hedge fund compliance officers to be entitled to the same protections as attorneys working in law firms, these protections must be conferred by statute. This approach creates a problem for legislators to solve where none existed previously. Prior to today, it was unnecessary for either Congress or this State’s Legislature to create a new rule to protect employees like Sullivan. The at will employment doctrine and the Wieder exception, both of which are creatures of common law, provide clear guidance. Rather than alluding to the possible creation of a new statutory remedy, this Court should instead properly apply Wieder.

In People v. Holland, 18 NY3d 840 (2011), Lippman dissented from the majority’s treatment of an attenuation analysis by the lower court — that is, an examination of whether police street conduct wrongly provoked conduct subsequently used to justify an otherwise improper search — as a mixed question of law and fact, outside the property scope of review by the Court of Appeals. Here again the refusal to address the issue on this tenuous ground marked an abdication of the Court’s proper role (18 NY3d at 845):

In […] pigeonholing this appeal as one involving a “mixed question,” the Court makes a choice that is not only unsound jurisdictionally, but erosive of this Court’s role in articulating the law governing police civilian encounters. The doctrine of attenuation in the search and seizure context is of course nothing more than a closely limited exception to the general, dominant rule that police intrusions must be justified at their inception (see Terry v. Ohio, 392 US 1, 19 20 [1968]; People v. Cantor, 36 NY2d 106, 111 [1975]; People v. Moore, 6 NY3d 496, 498 [2006]). If the exception is not to swallow the rule, care must be taken to assure that the doctrine is correctly employed.

He continued (id., footnote omitted):

When courts with the factual jurisdiction to make attenuation findings employ facile analytic shortcuts operating to shield from judicial scrutiny illegal and possibly highly provocative police conduct, an issue of law is presented that is, I believe, this Court’s proper function to resolve. . . . This is not an exaggerated or purely academic concern in a jurisdiction where, as is now a matter of public record, hundreds of thousands of pedestrian stops are performed annually by the police, only a very small percentage of which actually result in the discovery of evidence of crime.

“An issue of law is presented that is, I believe, this Court’s proper function to resolve:” At bottom, Lippman’s sensitivity to such issues, and his willingness to confront them and apply appropriate legal remedies, is perhaps the fundamental quality of his jurisprudence.

* * *

Yet however important his work as a leader of the Court of Appeals, adjudicating issues of broad legal and social consequence, Lippman’s primary legacy in office will arguably rest on his achievements as the chief executive officer of New York’s judicial branch — his continued shaping of the vision and direction of the Unified Court System.

Ongoing Innovation in State and National Court Leadership

Like the assessment of the legal philosophy of a sitting judge, examination of the direction of court system leadership in medias res is a tenuous exercise. This is especially so in the case of Lippman, whose early years of tenure were singularly ill-suited for administrative novelty. Shortly after he took office in 2009, New York State entered a major recession brought on by a nationwide housing bubble and banking crisis, leading to one of the most painful and difficult leadership periods in the court system’s history. In early 2011, the New York judiciary was compelled to cut its budget by $170 million; it was forced to monitor court hours, end overtime, suspend the services of judicial hearing officers, curtail numerous programs and services around the State, and lay off hundreds of court personnel. Much of Lippman’s early attention as chief executive during these difficult times was devoted to the preservation of fundamental court operations and the continuation of the numerous initiatives commenced during his service as chief administrative judge. For example, the court system’s electronic filing initiative grew apace, extending each year into new counties and new courts around the State, problem-solving courts expanded; court construction and renovation continued; numerous other programs were strengthened or maintained.

In addition, Lippman’s most consuming administrative effort during this early period was the resolution of the painful longstanding problem of judicial compensation. By mid-2010, New York’s judges had gone without a salary increase for more than eleven years — a stasis with significant consequences to judicial morale, retention, and recruitment. In November 2010, prompted by a series of developments — the Court of Appeals decision in Maron v. Silver,27 the ceaseless efforts of the Chief Judge to build support among bar allies, the press, and the business community, and the strong support of Governor Paterson in the waning days of his administration — the Legislature at last embraced a solution long championed by the courts: the appointment every four years of a Judicial Compensation Commission, empowered to review and recommend changes in judicial compensation which, in the absence of legislative countermeasure, would take effect by operation of law. Following public meetings and hearings, the first Commission determined in August 2011 that New York’s judges should receive a salary increase sufficient to place Supreme Court justices on par with the earnings of Federal District Court judges; the first portion of that increase became law on April 1, 2012. Thus this legislation solved, in a single stroke and in perpetuity, what had become New York’s most pressing problem of court operations, and simultaneously established the state as a leading proponent of judicial independence. It was an important victory for the new chief judge — all the more remarkable at a time of severe fiscal restraint.

Yet even while addressing these thorny issues, Lippman was singularly successful in articulating and implementing his vision of the primary goal of judicial branch leadership: redress of the problem of access to justice in a time of growing economic inequality. In Lippman’s view, this problem represented the principal crisis in contemporary American law, and imposed a constitutional and moral obligation upon judges, attorneys, and all who participate in the work of the judicial branch. As the guardians of an independent third branch of government, judges and court administrators had an obligation not only to provide justice to those who appear before the courts; they had a responsibility as well, to the extent that their delegated powers permit, to address the emerging economic and social problems that impede meaningful access to justice, especially among the State’s most vulnerable population. Such a duty was not abstract or academic; it was not an ancillary aspect of court operations to be sacrificed in difficult budget times. Instead it implicated the core values of the courts, and was inextricably entwined with their fundamental purpose.

In the early years of Lippman’s tenure, these core values were addressed in several distinct themes: the preservation of an independent judiciary; the establishment of reliable and substantial funding of indigent legal services, both criminal and civil (especially in areas of wrongful conviction and unjust residential foreclosure); and the ever-greater use of the court system’s resources — its brick-and-mortar facilities, its rule-making and administrative authority, and its institutional standing in government and the public eye — to ensure that the judiciary lives up to its constitutional mission to provide equal justice for all. As he noted in his 2011 State of the Judiciary address:28

As a Judiciary, we must stay true to our core values, to our constitutional mission, a mission as old as the biblical command: “Justice, justice, shall you pursue.” The pursuit of justice is an ongoing endeavor, a constant striving […]. Our Judiciary has long been a national incubator for innovation. Courts across America look to New York as a model for how to convert challenge into opportunity: how to reform one of the nation’s largest jury systems, how to reduce recidivism and break the cycles of addiction and violence, how to enhance transparency and accuracy in foreclosures. And while today’s problems press our justice system like never before, we do not have the luxury of shrinking from these challenges, because the pursuit of justice demands not only that we keep our courthouses open, but that we provide justice to our citizens in ways that are meaningful, equal for all, and absolutely fair and impartial. Anything less than that is not justice at all. I believe we must confront, right now more than ever, the challenges posed by record numbers of unrepresented litigants in civil matters involving basic life needs, spiraling home foreclosures, wrongful convictions that imprison the innocent and leave the guilty unpunished, a juvenile justice system that is failing our communities and our children, sentencing laws that are outdated and counterproductive, threats to public confidence arising from judicial campaigns, and fair compensation for judges.

The constitutional scholar Laurence Tribe phrased the problem in a sharper tone in remarks to the Annual Conference of Chief Justices in June 2010:29

Ours is supposed to be a system that levels the playing field by meting out justice without regard to wealth or class or race, a system that lives up to the promise emblazoned in marble on our Supreme Court, “Equal Justice Under Law.” But as you know all too well, far too many of our citizens find instead a system in which the deck is stacked in favor of those who already have the most: in favor of the wealthy and against those already disadvantaged or victimized by the more powerful. There’s no reason to mince words: Not only the poor but members of the shrinking middle class find a system that is confusing, difficult to navigate, challenging to the point of inaccessibility for anybody who can’t afford the best lawyers, and ridiculously expensive for those in a position to pay the going rate.

The Chief Judge’s commitment to the core values identified in his Judiciary message is manifest in numerous policies and programs enacted since he took office.

- In May 2010, Lippman established a Task Force to Expand Access to Civil Legal Services in New York, chaired by Helaine Barnett, former president of the Legal Services Corporation, and composed of judges, legislators, bar leaders, advocates, and academics. The task force was empowered to document the consequences of inadequate civil representation to impoverished New Yorkers and to propose judicial and legislative reforms, including funding reforms, to mitigate those consequences.30 In support of its work, the Chief Judge presided over extensive hearings on indigent civil legal services across the State in 2010, 2011 and 2012.31

- Since 2009, Lippman has worked assiduously to increase funding for civil legal services, adding $27.5 million and $40 million during the 2010-11 and 2011-12 budget years — by far the most state funding for civil legal services in the nation.32

- Commencing early in his term, Lippman devoted enormous attention to the pernicious consequences of the residential foreclosure crisis flooding the courts. He established pilot projects for pro bono representation of homeowners at foreclosure settlement conferences; instituted special calendars with bank officials to maximize the likelihood of settlement; and altered court calendaring practices to improve the effectiveness of settlement conferences. In late 2010, in response to the systemic nationwide problems arising from “robo-signing” and other documentary malfeasance in foreclosure cases, he required by rule that attorneys attest their diligent document review in filed foreclosure matters. (The volume of court filings dropped precipitously in consequence.)

- In May 2009, Lippman formed a Task Force on Wrongful Convictions, chaired by Court of Appeals Associate Judge Theodore T. Jones and Westchester County District Attorney Janet DiFiore, and consisting of representatives of the law enforcement, defense, judicial, legislative and academic communities. The Task Force has undertaken an extensive study of criminal justice practices in New York, has proposed numerous changes in law and procedure to eliminate wrongful convictions, and has had an influential impact on public debate over wrongful convictions in New York.

- Since 2009, the Court of Appeals intensified its scrutiny of the hundreds of criminal leave applications filed each year, and doubled the number of such applications granted for full bench review.

- In early 2009, the new chief judge helped negotiate a budget provision that established caseload limits upon criminal defense attorneys representing indigent defendants in New York City. In order to implement those limits over the following three years, the Judiciary expended more than $55 million from its coffers to indigent defense organizations — the first such initiative in the nation.

- In October 2010, Lippman established the New York State Permanent Sentencing Commission, composed of judges, prosecutors and defense counsel, academics, victims’ advocates, and government officials involved in criminal justices services. Chaired by Judge Barry Kamins and District Attorney Cyrus Vance, Jr., the Commission was empowered to review comprehensively New York’s sentencing laws and practices, to promote simplification and transparency in sentencing, reform in statewide sentencing policy, and increased attention to crime victims. Several of these proposals, including the expanded use of DNA databases by law enforcement, were later enacted into law.

- In 2011, he announced a court-administered initiative to provide attorneys for criminal defendants at arraignment, noting that the absence of counsel at such an appearance, where a defendant might be jailed indefinitely if unaffordable bail were set, is “a fundamental failure that can no longer be tolerated in a modern, principled society governed by the rule of law.”33

- In May 2012, he proposed the creation of a Youth Court for accused 16- and 17-year-old non-violent offenders, removing them from placement in adult confinement settings and making available treatment resources suitable to their age and development.

- In September 2012, he institute a requirement of fifty hours of pro bono service as a character and fitness standard for admission to the New York bar. Designed both to inculcate new attorneys with an awareness of their professional duty of service, and to help address the legal needs of the indigent, this requirement was the first of its kind in the nation.34

- In July 2011, Lippman implemented a rule requiring court administrative reassignment of cases where counsel or parties had contributed significant sums to the assigned judge’s recent election campaign — thereby applying an administrative solution to an ethical problem long deemed intractable. Again, this practice marked a national prototype.35

In addition to these and other program initiatives, Lippman has wholeheartedly embraced the public and symbolic nature of his office, both on and off the bench. To foster public support for and confidence in the Judiciary, he has been a relentless emissary and advocate on themes of court responsibility, delivering scores of speeches and remarks annually at conferences, fora, symposia, commencements, and other events around the State and nation. He has furthered the court system’s efforts at partnership with the multitude of state and national organizations devoted to court improvement — the Conference of Chief Justices, the National Center for State Courts, the State Bar Association, and countless others. He has elevated the public discourse, and the New York judiciary’s national profile, on the duties of a modern, independent and accountable Third Branch. (This visibility on the national stage was recognized in May 2012, when he was nominated by President Barack Obama to the board of directors of the State Judicial Institute, a national organization dedicated to improving the administration of justice in the state courts through innovation and better coordination with the federal court system.36) Whether by bully pulpit, legislative initiative, or creative use of court institutions and administrative rules, he has reshaped the court system’s capacity and conscience in resolving the “non-traditional challenges” of its operation, broadly understood. And yet he remains a work in progress. At this writing, his term on the Court is but half complete; three-and-a-half years remain of his allotted seven. What he will further accomplish in that time and after is unclear; but it can be safely assumed that this short term will exhaust neither his vision, nor his energy, nor his commitment to that great task.

* * *

Quoting a snippet from Archilochus (“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”), the British philosopher Isaiah Berlin famously suggested that intellectual and artistic personalities may usefully be categorized as either hedgehogs or foxes — those whose vision is derived from a single fundamental principle or perspective; or those who, in contrast, apprehend the world from diverse and often competing experiences.37 The first group includes figures such as Plato, Dante, and Hegel; the second, Shakespeare, Montaigne, and Goethe.

In this (admittedly flawed) classification scheme, Lippman’s worldview initially appears distinctly vulpine. As we have noted, his great strength in leadership rests in part upon an uncanny ability to appreciate multiple perspectives; to discern aspirations shared by antagonists; and to build coalitions and find goals held in common among surface adversaries. Throughout four decades in the court system, from entry-level attorney to Chief Judge, he has demonstrated an extraordinary flexibility of mind and dexterity in diverse roles and missions, succeeding brilliantly in an environment whose sheer scale and diversity dictates a multivariate perspective and approach to governance.

Yet in one key respect Lippman remains a classic “hedgehog”: his jurisprudential and judicial administrative work is animated by a singular relentless commitment to expanding the benefits of the rule of law to all, through the agency of an increasingly sophisticated, diverse, and independent Judicial branch. In this respect, Laurence Tribe’s comment to the Chief Judges in 2010 might have been written by Lippman himself:

My purpose is to challenge you to take up the task of improving our system, committing yourselves to fixing it. No one is better positioned than you to improve it. You are, quite literally, “Justice” — it is both your honorable title and your most solemn obligation — ensuring that justice is truly done in your systems. Like the Prophet Isaiah, you have touched the burning coal, you have the vision, you have the knowledge, and perhaps most importantly, your voices command the respect which will drive true reform. Ask yourselves, if not you, who?

The Lippman Chambers

A prerequisite of great leadership is exceptional staff, and Lippman has drawn a coterie of superbly able attorneys and assistants during his tenure, including Nathaniel Rudykoff, Anthony Galvao, Jennifer O’Friel, Joseph Bleshman, Cameron Moxley, and his extraordinary chief of staff, Jill Shukin. By all accounts, the Lippman chambers is “a fun and exciting place to work;”38 the Chief is known as a gracious and collegial boss, who brings out the best from his staff through careful delegation, unflappable support, and a shared dedication to both the principles and purpose of the law. As one former clerk noted, “[Y]ou cannot clerk for Chief Judge Lippman and forget for a moment that real people exist behind the caption of every case. This sounds exceedingly obvious, but it is a fact that many in the legal profession at times forget or fail to fully internalize. Results in litigation — and whether the parties are individuals or entities — not only matter at every stage, they affect the lives of actual people. Keeping this in mind as one handles a matter for a client as counsel or considers a case as judge helps to focus attention on the perpetual calling of our profession: achieving justice.”39

Family

Like many of his colleagues on the bench, Chief Judge Lippman has enjoyed felicitous domestic life. His wife of more than four decades, Amy Fiedler Lippman, recently retired from her position as a court attorney referee in White Plains. His son, Russell, and daughter, Lindsay, are also highly successful attorneys: Russell (B.A. Yale 1998 magna cum laude; J.D. Harvard 2001 cum laude) is a Vice President and Assistant General Counsel to AIG; Lindsay (B.A. Cornell 2001; J.D. Cornell 2004) is a counsel to MetLife in New York City. Russell and his wife Jennifer Ain Lippman (also a successful attorney) are the happy parents of Ryan Matthew Lippman, born May 26, 2012.

The Chief Judge also has three talented brothers — another lasting legacy of the parenting skills of Ralph and Evelyn Lippman. Jay is an internationally recognized ophthalmic surgeon in New York; Leonard is an accomplished obstetrician in Connecticut; David Lippman is the manager of a large cooperative supermarket in California — based upon the same Rochdale principles that underlay the establishment and operation of Cooperative Village so long ago.40

Endnotes

- See generally, Howe, Irving, World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made, 1976, New York University 2005, 26-63.

- Evelyn Lippman continued her education at the Bank Street School and NYU, and taught English at a local junior high for many years. One of her few regrets was her inability to find time and opportunity to obtain a Ph.D.

- See, Tony Schuman, “Labor and Housing in New York City: Architect Herman Jessor and the Cooperative Housing Movement,” (New Jersey Institute of Technology) (accessible at http://urbanomnibus.net/main/wp content/uploads/2010/03/LABOR AND HOUSING IN NEW YORK CITY.pdf ). For a brief history of Cooperative Village, see http://coopvillage.coop/-cvHistory.html. The importance of the ILGWU and Amalgamated to the economic and cultural history of the lower East Side (and elsewhere) has been set forth at length in Howe, op. cit., at 296-358.

- Hoffman, Jan, “New Assignment for the Court’s Point Man,” New York Times, July 5, 2000. See, “The Most Influential People in Cooperative Housing During the 20th Century: A Necrology,” 2000 Cooperative Housing Journal, pp. 6-16, at 13 (Ralph Lippman). To honor that service, a 1,000 seat hall, situated adjacent to Cooperative Village at 551 Grand Street and used for cooperative and community activities of all kinds for more than four decades, long bore the name=”Ralph Lippman Auditorium.”

- The Lippmans’ commitment to public social causes continued throughout their lives. Ralph was quite active in the United Jewish Appeal, the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies (receiving many honor awards for distinguished service), and the Educational Alliance (where he was elected to its Hall of Fame). Evelyn was involved with the Organization for Rehabilitation Training.

- Oxford/Guilford, located beside North Pond in Chenango County, played a major role in Lippman’s youth and early adulthood. He attended as a camper or counselor every summer between 1957 and 1967. In the summer of 1967, he met Amy Fiedler, a fellow counselor at the camp; the couple married two years later. Although Oxford/Guilford ceased operations around 1986 (and was succeeded by Camp Mesorah), it continues to have an enthusiastic alumni/ae following. See, e.g., http://oxfordguilford.homestead.com/mainpage.html (accessed May 8, 2012).

- And this to great effect: three of the four Lippman sons attended Stuyvesant High School; all four obtained college degrees; two became doctors and one an attorney (and chief judge).

- Diamond, Interview with Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman, Brooklyn Barrister, Vol. 63, No. 5, 2011, p. 1).

- For a fine analysis of these developments, see Bloustein, Marc, “A Short History of the Unified Court System”, December 5, 1985 (http://www.nycourts.gov/history/elecbook/short__hist/pg1.htm).

- Lippman, Remarks (upon receipt of the Award for Conspicuous Public Service), New York County Lawyer’s Association, September 28, 2006, pp. 1-2.

- See, Diamond, op. cit., at 1.

- See, Wise, Daniel, “New Administrator Knows Court System From the Ground Up,” New York Law Journal, November 30, 1995; Hoffman, op. cit. (“He is said to know more about how the system works than anyone else ….”).

- Caher, John, “An Optimist Survives in a Job With High Burn-out Rate,” New York Law Journal, December 27, 2000, p. 1, col. 3.

- See, e.g., Wise, Daniel, “Tireless Optimist Guided Courts Through Dynamic Changes,”, NYLJ, October 9, 2007, p. 1, at p. 18, col. 4.

- See, Lewis, David L., “Judge Without a Gavel: Jonathan Lippman still has huge effect on courts,” New York Daily News, February 28, 1998, p. 17:1 (quoting then-Judge Barry Cozier: “His greatest asset is his ability to establish rapport in really an impartial and non-partisan manner with just about anyone.”) ; Wise, “New Administrator Knows…,” op. cit. (quoting John F. Werners description of Lippman as “‘a perfectionist with an enormously engaging personality who made fast friends’ with people through the 60 Centre Street courthouse”). As one senior judge later commented admiringly: “That guy really knows how to schmooze!”

- Among court system insiders, this quality was sufficiently distinctive to merit its own lampoon: “Lippmanize” was humorously defined as persuasion, through friendly conversation, of persons deemed unconvinceable to positions deemed insupportable.

- Caher, John, “An Optimist Survives in a Job With High Burn-out Rate,” New York Law Journal, December 27, 2000, p. 1, col. 3 (“The fun for me is to live in this multi layered world, with the complex problems we have, and figure out how to get from A to B, how to solve the problem and get it done. Do I feel tired? Yes, often. Do I feel dispirited? Yes, often. But I can honestly say that every morning when I get up I have that resilient feeling and I want to get out there and solve our problems.”)

- The others were the Hon. Richard J. Bartlett (1974-1979); Hon. Herbert B. Evans (1979-1983); Hon. Robert J. Sise (1983-1984); Hon. Joseph W. Bellacosa (1985-1987); Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (1987-1989); Matthew Crosson (1989-1993); and Hon. E. Leo Milonas (1993-1995). Following Judge Lippman were the Hon. Ann Pfau (2007-2011); and Hon. A. Gail Prudenti (2011-present).

- See, Crane, “Judith Kaye,” in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals — A Biographical History (Rosenblatt, ed.), Fordham University Press, 2007, pp. 803-826.

- Although this list is sharply circumscribed, one additional achievement merits mention. In the aftermath of the terror attacks of September 11, 2001 — a stone’s throw from the Courthouses in Foley Square and many downtown court offices — RLippman spearheaded the response that kept courthouses open in lower Manhattan. Within days, judges and court staff had reopened the ten court facilities in the downtown “frozen zone,” instituting security patrols and measures, setting magnetometer and x-ray checkpoints, implementing a secure attorney identification system, and establishing new practices for emergency responsiveness coordination with federal, state and local authorities.

- Judge Lippman served the Conference of State Court Administrators as a director (1996-2007), president (2005-2006), and chair or co-chair of various committees; he served the National Center for State Courts as a director (2003-2007), vice-chair (2005-2006), and budget committee chair (2003-2006).

- Quoted in Caher, “An Optimist Survives…,” op. cit., p. 1, col. 3.

- In United States v. Jones, __ U.S. ___, 132 S. Ct. 945 (2012), a unanimous Supreme Court held that a warrantless installation of a GPS device violated the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution. In her concurring opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor quoted Lippman’s Weaver opinion to highlight the intrusive nature of such surveillance, and its worrisome implications for personal privacy. 132 S.Ct. at 955 (Sotomayor, J., concurring).

- Glaberson, William. Dissenting Often, State’s Chief Judge Establishes a Staunchly Liberal Record. New York Times, October 9, 2011.

- See, e.g., Galvao, Antonio E., “Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick,” in Rosenblatt (ed.), The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals, op. cit., at 921.

- Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S.335 (1963).

- In Maron, 14 NY3d 230 (2010), the Court held that the principle of separation of powers barred the Legislature’s practice of postponing consideration of judicial salary increases through the “linkage” of that issue with other, unrelated matters. Chief Judge Lippman did not participate in that decision.

- Lippman, “Pursuing Justice,” State of the Judiciary 2011, February 15, 2011.

- Tribe, Laurence H.. Keynote Remarks at the Annual Conference of Chief Justices. Vail, Colorado, July 26, 2010. At the time of these remarks, Tribe was senior counselor for access to justice at the United States Department of Justice.

- Lippman, “Law in the 21st Century: Enduring Traditions, Emerging Challenges” (Law Day Remarks), May 3, 2010.

- See, “Report to the Chief Judge of the State of New York,” The Task Force to Expand Access to Civil Legal Services in New York (November 2011). These hearings are designed to take place annually.

- These allocations were not only novel: they came at a time when the Judiciary faced substantial cutbacks in its operating budget, and ultimately was required to curtail other court operations and reduce staff. Faced with agonizing choices, Lippman determined that the need to lay the groundwork for civil services funding was simply too important to postpone.

- Stashenko, Joel, “Lippman Vows to Correct State’s Failure to Provide Attorneys for Indigent Defendants at Arraignment,” NYLJ, May 3, 2011, p. 1., col. 3.

- In January 2010, Chief Judge Lippman established the Attorney Emeritus Program, amending New York’s attorney registration rules to encourage experienced or retired attorneys to provide pro bono legal assistance to underserved New Yorkers.

- See, e.g., Glaberson, William, “New York Takes Step on Money in Judicial Elections,” NY Times, February 13, 2011; Skaggs, Adam, “Victory for Recusal Reform in New York,” Brennan Center for Justice, February 14, 2011 (www.brennancenter.org/blog/archives/victory_ for_recusal_reform_in_new_york/).

- Caher, John. “Lippman Nominated to Board Position of State Judicial Institute.” NYLJ, May 24, 2012, p. 1, col. 5.

- Berlin, “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” in Hardy and Kelly (eds.) Russian Thinkers, Pelican Books, 1979, p. 22.

- Cameron Moxley, Clerking for the Chief, Albany Law Review, Vol. 75.2, pp 645-646, n. 1 (March 2012).

- Moxley, op. cit., at 646. For several delightful vignettes recalled by another former clerk, see Margaret Nyland Wood, “More Than Meets the Eye: A Clerk’s Perspective of Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman,” Albany Law Review, Vol. 75.2, pp 647-649 (March 2012).

- See, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cooperative_Village (accessed May 8, 2012); http://www.northcoastco op.com/about.htm (accessed May 8, 2012).