C. The Foster Memorial

Not long after Mrs. Foster’s death a campaign was organized to finance a fitting public tribute in her memory. The idea was suggested by the City Club, the trustees of which assigned the task of arranging the details and procuring the necessary funds to one of the Club’s committees. Capt. F. Norton Goddard, the treasurer of the fund, issued a public appeal for subscriptions. He wrote to various noteworthy persons and solicited from them letters supporting the campaign and describing “the thorough excellence of [Mrs. Foster’s] work, and the great beauty of her character.”[221] In May 1902, the New York Times reported that the fund “is receiving replies that are quite encouraging. But a considerable sum is required to provide a dignified and beautiful work of art which shall fitly perpetuate the memory of Mrs. Foster.”[222]

The Times described some of the responses received:

District Attorney Jerome, in forwarding a check, eulogizes Mrs. Foster and declares that any language approximately describing her work would seem extravagant. In addition he said: “In pursuit of the work to which she was devoted, I have known her to go on until from sheer exhaustion she fainted away …”

In transmitting his check ex-District Attorney Philbin warmly commended the plan, and paid a high tribute to Mrs. Foster, saying among other things: “It was Mrs. Foster’s practice to visit the prisons and the Tombs, and in a quiet, unaggressive manner appeal to the better feelings of the inmates. Although herself of high social standing, she was able to have a thorough sympathy not only for the unfortunate circumstances that caused imprisonment, but also as to the environment whence the prisoner came … This great work of charity differed from any other that I have ever known in that, although a great volume of work was accomplished, practically no part of the funds furnished from time to time by Mrs. Foster’s friends was used in the expenditure of salaries or other items, but the money supplied was used almost exclusively for the aid of the unfortunate.”[223]

And this article contains this remarkable tribute by a former District Attorney:

In announcing his readiness to contribute to the fund ex-District Attorney W.M.K. Olcott said: “Mrs. Foster’s deplorable death will be felt with more poignant sorrow and for a longer time and by more people than that of any one with whom I have ever come into contact. Her work was painstaking and thorough and tactful and inspired. Her memorial will not only commemorate herself and her good deeds, but will urge others to profit by some of the graces of her good example, and so your work will continue the beneficence of hers.”[224]

In his efforts to secure endorsements for this project and to generate funding for it from the public, Goddard wrote to the Secretary to President Theodore Roosevelt. That letter bore fruit. President Roosevelt sent the following letter dated April 21, 1902:

My Dear Captain Goddard:

I gladly enclose my subscription to help erect a monument to Mrs. Rebecca Salome Foster, better known as the “Tombs Angel.” It is a very real pleasure to testify even in so small a way to her work.

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt[225]

We do not know whether President Roosevelt ever met Mrs. Foster. But Roosevelt had grown up in an atmosphere of concern for social improvement as a result of the activities of his beloved father. Theodore Senior, who had been deeply religious, had helped to create the Children’s Aid Society to support the city’s homeless children. He had been instrumental in the establishment of the Newsboys’ Lodging House, which provided accommodations for several hundred stray boys nightly, and he spent part of every Sunday working with the boys there. He also helped to start the New York Orthopedic Dispensary and Hospital, which provided treatment for children with deformities.[226] Theodore Junior was a prominent reformer active in Republican politics in New York City who, after an unsuccessful campaign to become Mayor of the City of New York, served as President of the Board of Commissioners of the New York City Police Department, the headquarters of which were located at 300 Mulberry Street, between Houston and Bleecker Streets, not far from the center of the Five Points neighborhood, from 1895 to 1897, while Mrs. Foster was at work. He was a close personal friend of Jacob Riis, who wrote a biography of him in 1904, and was strongly influenced by Riis’s work on the tenements of New York. As President of the Police Commissioners, Roosevelt would prowl the streets of the city in the dead of night and the early morning checking on the activity of his police officers, and Riis would sometimes accompany him. Roosevelt fought against and reduced politics, ethnic discrimination, and corruption in the police force.[227] Roosevelt “personally brought about the closure of a hundred of the worst tenement slums seen on his famous night patrols.”[228] After he became Governor of New York, Roosevelt established a Tenement House Commission to address problems in those troubled areas so well documented by Riis. Thus, Roosevelt was very familiar with the Five Points, tenement life, crime in the city, the effects of poverty on the young and immigrants, and the needs of the poor, particularly the young, and so it is reasonable to conclude that he knew of Mrs. Foster and her work while serving as President of the Police Commissioners and afterward. Incidentally, the Roosevelt family home at 28 East 20th Street was only a block or so away from Calvary Church.

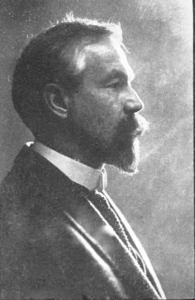

A number of articles about the progress of the public subscription appeared in the newspapers in the months that followed its initiation. In due course sufficient funds were raised to finance a suitable monument to Mrs. Foster. Karl Bitter was commissioned to create the work, and Charles R. Lamb (1860-1942) was chosen, perhaps by Bitter, to produce the metal frame.

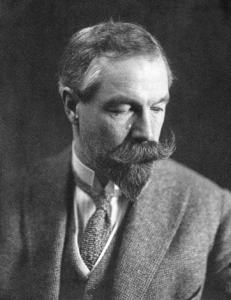

The selection of Karl Bitter for the commission was a reflection of the admiration felt for Mrs. Foster by the supporters of the campaign. Karl Bitter was one of the most celebrated and respected sculptors of his time. He was born in Austria in 1867 and studied in Vienna at the School of Applied Arts (1881-1884) attached to the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry, with the intention of becoming a landscape painter. Gradually, he became interested in sculpture. From 1885-1888. he studied at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. During this period, he also worked as an assistant to established sculptors on the ornamentation of public buildings and he apprenticed as a stone carver. In pursuing an artistic life, Bitter acted in defiance of his father, who was a stern disciplinarian and wished his sons to become lawyers. Bitter came to America when he was 22, in 1889, while Mrs. Foster was working in the Tombs. As was true of so many immigrants before and has been true since, Bitter arrived with very little — a bag weighed down with the tools of his profession, virtually no English, a German-English dictionary, no connections in America, no letters of introduction, and only a few dollars in his pocket. Bitter’s education, experience, and talent saved him from the rigors of the tenement life that otherwise might have awaited him. Within days of his arrival in New York, good luck came to him and he chanced to find work modeling figures in clay for a firm of architectural decorators. Within a few weeks thereafter, his work came to the attention of Richard Morris Hunt, the firm’s most important client and one of the most prominent architects in America. Hunt became a mentor to Bitter. He urged Bitter to leave his job and set up a studio of his own, which Bitter did, on East 13th Street, and Hunt referred much decorative work to him for projects Hunt had in progress. In this early period, Bitter learned about a prize competition for bronze doors for Trinity Church, Wall Street, in New York, for which John Jacob Astor had left money in his will. Bitter submitted a design and in 1891, when he had been in America only 16 months and was only 23 years old, he won the prize for the main door on Broadway. The door was created and installed, and this success, together with the support of Hunt,[229] firmly set Bitter on his career.[230]

In the first stage of his career, Bitter did decorative sculpture. He did work for the Astor, Huntington and Goodyear residences, the Long Island home of William K. Vanderbilt, the Park Avenue mansion of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, and, later on, for the garden of Kykuit, the Rockefeller estate in Westchester County, New York. He provided decorative sculpture for the Vanderbilt mansion, the “Breakers,” in Newport, Rhode Island,[231] as well as extensive work at Biltmore, the estate of George W. Vanderbilt in Asheville, North Carolina, the largest home in the United States.[232] These commissions gave Bitter financial security such that he was able, at only 28, to commission the construction of a home and studio for himself on the edge of the New Jersey Palisades in Weehawken, which was completed in 1897.[233]

By the beginning of the new century Bitter had turned from privately commissioned ornamental works and increasingly focused his energies on architectural sculpture, sculpture that sought to adorn and to enhance the beauty of buildings, of which a great many were being built in the ever-more-prosperous country. The creation of such sculpture was challenging because it had to be, of course, beautiful and of high quality, but also must be in harmony with the designs and intentions of the architects. Among his architectural efforts were many works for the exterior of the Broad Street Station in Philadelphia, as well as a frieze 30 feet in length for the interior entitled “The Progress of Transportation” (1895);[234] a medallion on the Custom House Building in lower Manhattan;[235] a group for the exterior of the Appellate Division, First Department, in New York City (“Peace,” on top of the balustrade facing Madison Square) (1900); four figures on the exterior of the Metropolitan Museum of Art facing Fifth Avenue (1901);[236] and a significant amount of work for the new Wisconsin State Capitol Building in Madison (1911).[237]

In addition, Bitter was also called upon to create portraits, sculptures of figures, reliefs, monuments, memorials, and other kinds of work. Among his impressive designs with historical themes were a monument commemorating the signing of the treaty effecting the Louisiana Purchase for the Missouri Historical Society and large-scale figures of Thomas Jefferson on three occasions, for the Jefferson Memorial at the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis, the new Cuyahoga County Courthouse in Cleveland, Ohio (along with a flanking sculpture of Alexander Hamilton, also by Bitter), and at Jefferson’s university, the University of Virginia (a modified, smaller version of the Missouri work).[238] Bitter is said to have been the first artist to have attempted a major portrait of Jefferson since his death in 1826.[239] Bitter also created a sculpture of Henry Hudson now located in Henry Hudson Park, Bronx, New York.[240]

Other noteworthy commissions are the full-scale relief of Dr. Henry Tappan, President of the University of Michigan, and full sculptures of Dr. William Pepper at the University of Pennsylvania and Dr. Andrew White at Cornell; the Villard Memorial in Sleepy Hollow, New York; the equestrian statue of Civil War General Franz Sigel on Riverside Drive and 106th Street in New York City (the monument committee for which included Carl Schurz, in whose home the group met);[241] and the Carl Schurz Memorial located at West 116th Street overlooking Morningside Park in New York City.[242] Bitter selected the impressive sites for both the Sigel and Schurz monuments, which he was not always able to do with his commissions. Bitter worked on the Dewey Triumphal Arch on Fifth Avenue at 24th Street in New York City in 1899 along with colleagues from the National Sculpture Society, including Charles Lamb, one of its founding members, who designed the arch.[243] The Breckenridge Memorial by Bitter is a tablet at the United States Naval Academy commemorating an ensign lost at sea in the Spanish-American War. A number of Bitter’s works are in the Metropolitan Museum, including the All Angels’ church pulpit and choir rail (1900), which is on display in the great atrium of the Museum’s singularly important American Wing.[244]

Bitter also spent much time in promoting sculpture at important expositions. He worked on sculpture groups at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. His creativity and skill at the administration of large projects became well-known in the profession and, together with the general advancement of his career and accomplishments, led to leading roles at three subsequent expositions. He served as the director of sculpture at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York of 1901.[245] He was chosen for this position by a unanimous vote of his peers at the National Sculpture Society, a high honor reflective of the respect in which he was held in the profession.[246] The architects’ plan for the exposition specified how much sculpture should be employed and the relative size of the various groups, but it was left to Bitter to determine the subjects and designs for all of the many works that would be used. He decided not just the general themes for the sculpture, but the subjects for each subordinate group, and he contributed some work of his own as well.[247]

In 1904, Bitter again served as the director of the department of sculpture at the St. Louis Exposition, at which the Louisiana Purchase was celebrated, which position required him to design the sculpture theme for the exposition, assign the work to groups of sculptors, evaluate their performances, and supervise the enlargement and placement of each group. This was a massive undertaking since there were some 250 groups and over 1,500 single figures to be completed and installed, all within a matter of months. To do this work, Bitter established an enlarging shop in Weehawken and had shipped from there to St. Louis 54 railcar loads of full-scale sculpture in staff.[248] He was also the director of sculpture for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.

Bitter had a serious interest in improving the artistic patrimony of the cityscape and rendering it more aesthetically pleasing for the benefit of all citizens, particularly as New York City grew in size and prosperity. This no doubt explains his service (without pay) beginning in 1912 on the Art Commission of the City of New York, which was established in 1898, and of which he was twice chosen a member. He wrote an extensive article on the subject of sculpture in urban settings, arguing that attention needed to be paid to the employment of suitable sculpture to enhance the public and aesthetic life of the city, including use, carefully planned, of “a definite program or system which would bring about an aesthetic and harmonious development of [all large] public squares.”[249] In the article, he discussed the potentialities of many leading public areas in the city, such as Battery Park and Washington Square Park, and the weaknesses of the current state of those spaces. One of the areas about which he was particularly concerned over many years was Fifth Avenue between 58th and 60th Streets and the entrance to Central Park. Inspired by the Place de la Concorde in Paris, he advocated that the entire area needed to be addressed by a comprehensive plan that would create an impressive space suited to the importance of the area and he sketched a design for the kind of thing he had in mind. He made a presentation on this subject to the National Sculpture Society, which appeared in print.[250] His interest in the Plaza area led to his involvement in the planning for the Pulitzer Fountain outside the Plaza Hotel, so-named because the funding for the project was left by Joseph Pulitzer in his will. Bitter was chosen to create the figure that stands atop the fountain, Pomona, the goddess of Abundance. The scale model of this figure was the last work touched by Bitter before his death.

Among the honors he received in his career were the silver medal of the Paris Exposition in 1900, the gold medal of the Pan-American Exposition of 1901, a gold medal at Philadelphia in 1902, and the gold medal of the St. Louis Exposition in 1904.[251]

He was three times elected President of the National Sculpture Society;[252] was a member of the National Institute of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Design, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Players’ Club, and the Century Club; and served as an officer of the Architectural League.[253] His tenure on the Art Commission is interesting and ironic in that the Commission and its successor played important roles in the story of the Foster Memorial, as will be noted below.[254]

Bitter’s Carl Schurz Memorial has a connection to Foley Square, 60 Centre Street, and the old Five Points neighborhood where Mrs. Foster worked, inasmuch as city planner and preservationist George McAneny (1869-1953), who is given great credit for the movement of the New York civic center north of Chambers Street, and the development of Foley Square and of 60 Centre Street itself, was a protégé of Carl Schurz, who, let us recall, had been an active supporter of Bitter’s Franz Sigel equestrian statue. McAneny was a friend of Bitter, worked with him on the Schurz Memorial project, and spoke about him at the memorial given after his death. McAneny recalled “the pains, the infinite pains, that [Bitter] took with [the Schurz Memorial] and his feeling from the beginning that here was an opportunity to preserve every trace … to give the form and features of the man who had meant so much to those who had, like [Bitter himself] had, come across the seas and found their opportunity in America …”[255] McAneny was certainly correct about the pains that Bitter took with this project: the planning and execution of the Schurz monument occupied him over the course of five years.[256]

The movement of the civic center north of Chambers Street advocated by McAneny had as an aim the elimination of the blighted area of the Five Points and its replacement by what are today multiple state courthouses, including the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County, and three Federal courthouses, as well as other state and Federal office buildings.[257] When the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Federal Courthouse at 500 Pearl Street was being developed (it opened in 1996), an archaeological excavation was undertaken by the General Services Administration. The basements of many tenements of the former Five Points neighborhood were located and over 850,000 19th century artifacts were uncovered, including everyday household items. After construction was completed, some of these artifacts were put on display in an exhibition in the new courthouse. The immigrants and other impoverished residents of the Five Points would surely have been amazed had they known that such an exhibition could ever take place. This coda to the history of the Five Points, once visited by Dickens, Jacob Riis, and other worthies, the center of much of the work of Theodore Roosevelt and his police officers and of Mrs. Foster, intersected with another critical moment in the history of New York City: after the exhibition closed, the artifacts were moved for safekeeping to the basement of 6 World Trade Center and almost all of them (all but a few from some Irish tenements and a saloon that were on loan elsewhere) were there destroyed on September 11, 2001.[258]

The monument to honor the work and memory of Mrs. Foster that was produced by Bitter and Lamb was a wall mounting approximately seven feet high consisting of an elaborate, renaissance-style bronze frame, a marble medallion at the top bearing the likeness of Mrs. Foster, and, in the center, a large marble relief of an angel, the focal element to the composition and an allusion, of course, to Mrs. Foster’s unofficial title, “the Tombs Angel,” to which no express reference was made on the memorial. The winged angel supports a young boy in need by the shoulders from the rear and appears to be speaking words of hope and encouragement to him. Bitter created the medallion and the relief.[259] He may have designed the frame as well since the model from his studio included the frame in plaster.[260] The relief was signed by Bitter (in Latin, “Karl T.F. Bitter, Conceived and Executed 1903”). Not on the relief but underneath it on the frame were Mrs. Foster’s name and dates and the words, very apt ones, “On Her Lips Was The Law of Kindness.”[261]

The Foster Memorial was publicly unveiled by Karl Bitter himself in a ceremony at the City Club on January 1, 1904 that was attended by Mrs. Foster’s two daughters[262] and a photograph of the Memorial appeared in a newspaper around the same time.[263] The installation of the monument took place in 1904 in the Criminal Courts Building, Court of Special Sessions, across Franklin Street from the site of the original Tombs Prison and that of its successor.[264] The initial plan had been to install the tribute in one of the courtrooms, but at the suggestion of the judges it had been decided instead to place it in a heavily-trafficked hallway, no doubt so that the public could more readily see it.[265] An installation ceremony was apparently held in April 1904,[266] undoubtedly attended by Mrs. Foster’s daughters, judges, members of the Bar, and the staff of the courts. In 1906, Bitter presented what evidently was a model or the drawings for the Foster Memorial at an annual exhibition of the Architectural League of New York.[267]

In the years after the installation of the Foster Memorial, the career of Karl Bitter continued to flourish and his influence within his profession continued to grow. But then, life linked him again to Mrs. Foster and her fate, in a different and tragic way.

In 1903, while Bitter may have been at work on the Memorial, he was traveling in a horse-drawn carriage in Manhattan when the horse bolted. The carriage overturned and he was thrown out in the street. Fortunately, he was unhurt.[268]

In April 1915, however, as he and his wife were leaving the old Metropolitan Opera House and crossing Broadway, he was hit by a swerving automobile. He died the next day. It was a sad irony that an artist who had once sculpted a paean to the progress of transportation should meet such an end. His wife, Marie, survived without serious injury because he had pushed her out of the way at the last instant. As had been the case with Mrs. Foster, his last thought in the accident that took his life was of someone else.[269] He was only 47 years old.

Table of Contents

A. Introduction

B. The Life and Work of Rebecca Salome Foster

- The Backgrounds of Rebecca and John A. Foster

- New York City in the Late 19th Century

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Began

- What Mrs. Foster Did for Prisoners, Their Families, the Courts, and Others

- Mrs. Foster’s Work in Her Own Words

- Funding the Work

- Providing Legal Assistance

- Traveling Throughout the City and Elsewhere

- The Tombs and “Five Points”

- How Mrs. Foster’s Work Came to an End

D. What Happened to the Memorial

E. The Foster Family and a Home for the Marble Relief

G. Endnotes