This blog article was written by John Oller, an author and retired New York lawyer whose latest book is White Shoe: How a New Breed of Wall Street Lawyers Changed Big Business—and the American Century (Dutton, March 2019), from which his upcoming Judicial Notice Issue 15 article, “George Wickersham: ‘The Scourge of Wall Street,’” is adapted. He may be found at www.johnollernyc.com. Below is a preview of the article.

Judicial Notice is a members-exclusive publication! Make sure to join or renew your membership to receive your copy.

Join or Renew Your Membership

Introduction

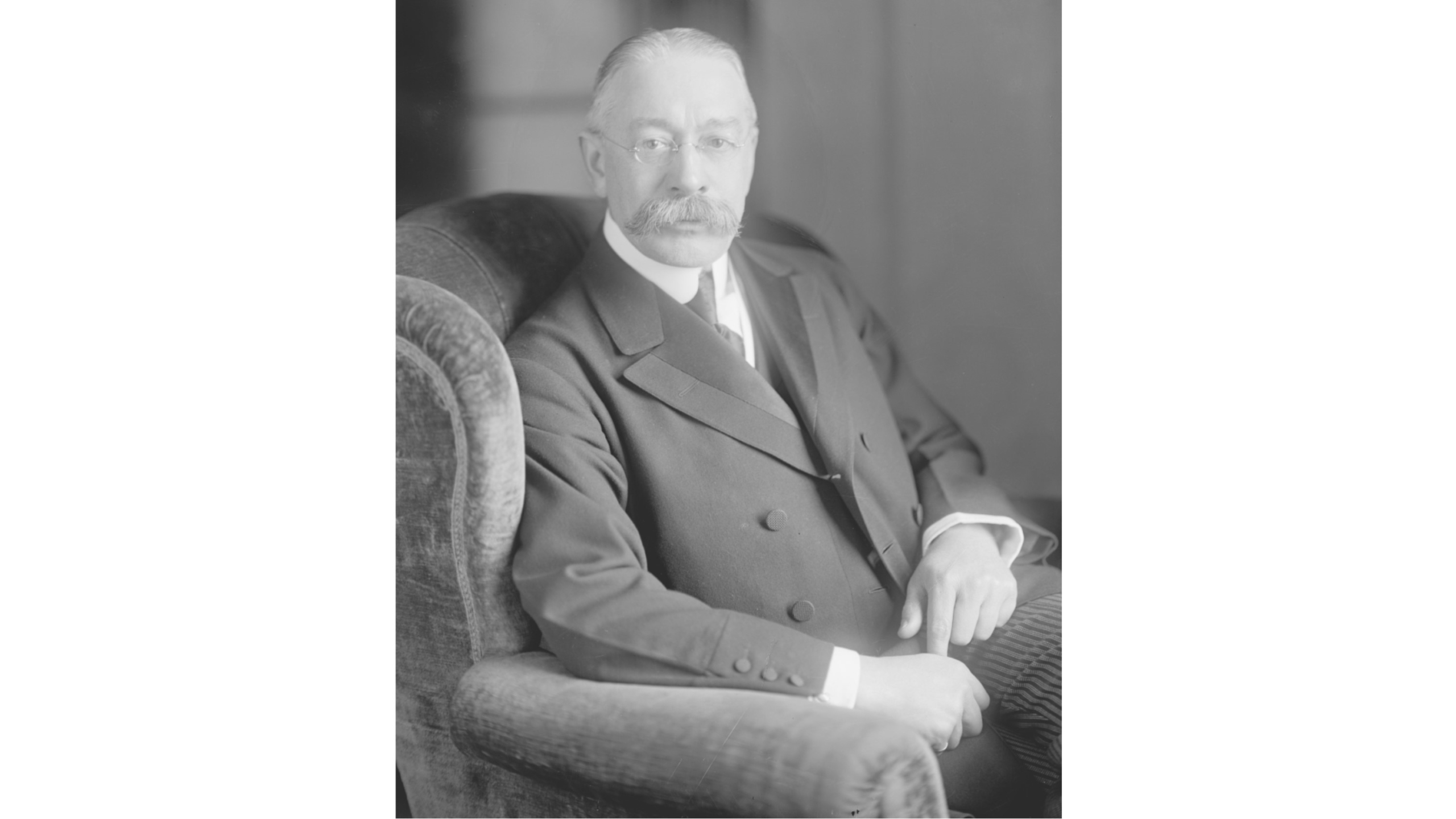

In New York legal circles today, the name Wickersham is most closely associated with the law firm of Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, the oldest in New York City. The actual man behind the name, George Wickersham, is less well known to current generations. Yet from roughly 1900 to his death in 1936, George Wickersham was one of the most renowned and influential lawyers of his time. He began his career creating and defending large corporations, then switched sides, as US attorney general under William Howard Taft from 1909 to 1913, to become known as “the scourge of Wall Street” for his aggressive prosecution of antitrust cases.

Early Life and Career

Born in Pittsburgh in 1858, Wickersham started out at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania intending to become civil engineer, but a literature professor who spotted in Wickersham a taste for letters persuaded him to “give up the study of calculus for that of Blackstone.” He obtained his law degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1880 and moved to New York City in 1882 to take a clerkship with the firm of Chamberlain, Carter & Hornblower. It was a progenitor of the “white shoe” firms and lawyers who would dominate the legal world for many decades of the twentieth century.