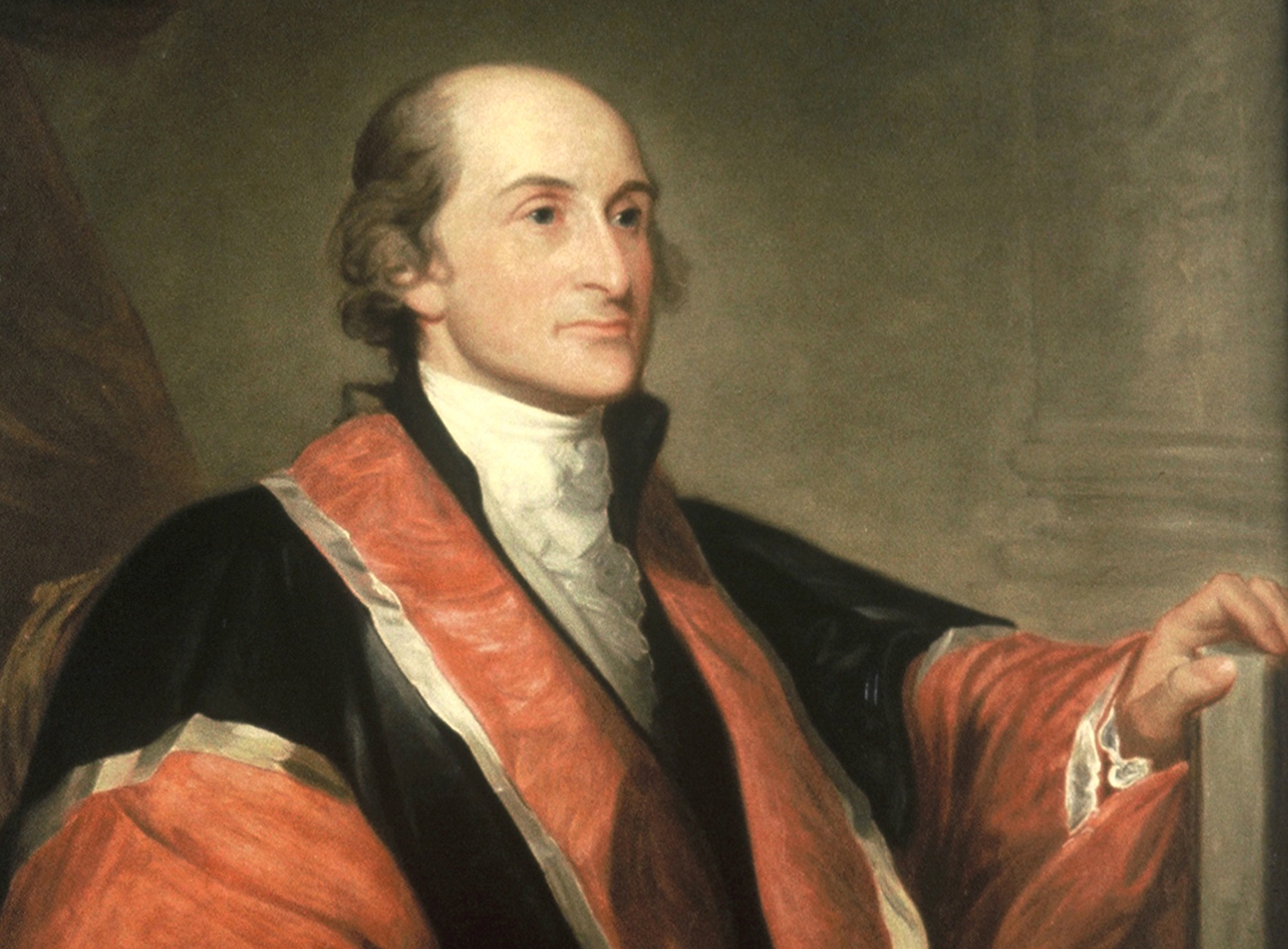

This blog article was written by Hon. Mark C. Dillon, and it’s a preview of his Judicial Notice Issue 15 article on John Jay. Mark C. Dillon is an Associate Justice of the Appellate Division, Second Judicial Department of the New York Supreme Court, an Adjunct Professor of New York Practice at Fordham University School of Law, and an author of the McKinney’s CPLR Practice Commentaries. He has authored By The Light of My Burning Effigies: Chief Justice John Jay in the Struggle of a New Nation, a book that is being published in 2020 by SUNY Press.

Judicial Notice Issue 15 is on the way, but we ran into a slight delay and are unable to send the newest edition to your homes. Who are the four men profiled in this new issue? Find out each week as our authors preview their impressive articles.

There is a misperception that the 1804 case of Marbury v. Madison was the first decision of the U.S. Supreme Court of great constitutional importance. Instead, the first case of great constitutional magnitude was the 1793 case of Chisholm v. Georgia, the third case ever decided by the Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Jay, of Westchester County, was at the center of the political and judicial maelstrom that surrounded Chisholm.

Chisholm arose from the failure of the framers of the 1789 constitution to clearly address the question of whether the sovereign states could be sued as defendants in the federal courts. There is evidence, including Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist Paper #81, that the drafters of the constitution did not intend for the states to be subject to federal suits, which was among the assurances that the states relied upon in ratifying the constitution. The actual constitutional language that was ratified, however, said in Article III section 2 that the federal courts could hear suits “between a State and Citizens of another State.” Creditors who were owed money from the near-bankrupt states soon tested the constitutional language by bringing suits against them, and the Chisholm case was the first such action to reach the Supreme Court. Chisholm raised the question of whether the concept of constitutional “originalism,” at a time when all jurists were originalists, was to be guided by the intent of the drafters or, alternatively, by the plain language of the constitution itself. Usually, there is no difference between intent and plain language, but in the case of Chisholm, the difference was glaring.

All members of the U.S. Supreme Court during John Jay’s tenure as Chief Justice were Federalists. There were three aspects of Jay’s personal and professional life that predisposed him to believing that debtors be held to account in courts. When Jay was a child, his father, Peter Jay, retired from mercantile trade and spent the following three years collecting debts from creditors, amounting in today’s dollars to approximately $1.1 million. As a New York attorney, a portion of Jay’s law practice was representing clients in debt collection matters. And as a negotiator with Benjamin Franklin and John Adams of the Treaty of Paris, which formally ended the Revolutionary War with Great Britain, Jay help write a provision that each nation honor the debt collection efforts of its citizens in the courts of the other nation.

The State of Georgia, which owed money to plaintiff Alexander Chisholm, refused to defend itself in any court on the ground that it was immune to suit as a state sovereign. The Supreme Court held, in a 4-1 vote, that the plain language of the Article III section 2 of the constitution permitted the suit by Alexander Chisholm against the state. John Jay’s opinion defined “originalism” as reliant upon the constitution’s plain language, and not the intent of the drafters.

The Chisholm opinion was controversial. The Massachusetts legislature voted on September 27, 1793 to openly defy the Supreme Court by refusing to submit to the jurisdiction of the federal courts, which set a tone that many other states then followed. Not to be outdone, Georgia’s House of Representatives passed a Resolution on November 27, 1793 declaring anyone who sued the state guilty of a felony and be hanged, without benefit of clergy. The impasse risked a constitutional crisis between the federal government and the individual states. There was such a public outcry against Chisholm’s extension of federal authority over the individual states that an 11th Amendment to the constitution was drafted, enacted, and ratified to assure, by its language, that the states not be subject to the jurisdiction of the federal courts. Despite winning his case at the U.S. Supreme Court, Alexander Chisholm never actually recovered a dime of his claim. But John Jay’s definition of originalism influenced constitutional thought in the two centuries that followed, to a greater degree than the monetary value of Chisholm’s singular case.

Comments · 1

Comments are closed.