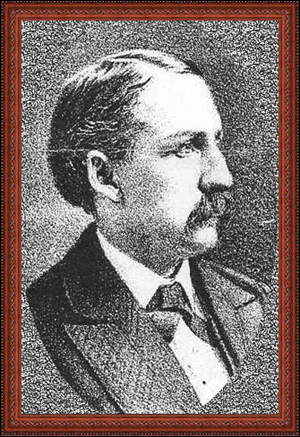

Whatever his gifts as a judge, history remembers Isaac Horton Maynard more for the questionable conduct that allegedly won him appointment to the Court of Appeals than for his decisions or comportment on the bench. The degree of ignominy associated with Maynard’s name is as tragic as his downfall, especially given his ability and the abundant promise he exhibited early in his career. Although largely forgotten today, the scandal that dogged Maynard was well known and widely reported to his contemporaries, and it represents one of the more colorful incidents in the Court’s past.

Isaac Maynard was born in Bovina, in Delaware County, New York on April 9, 1838 to Isaac and Jane (Falconer) Maynard. His great-grandfather, Isaiah Maynard, emigrated to Westchester County from the north of England about 1750. His grandfather, Elisha B. Maynard, distinguished himself as a soldier during the Revolutionary War and afterwards settled in Bovina. His father, Isaac, was prominent in the town, serving as Magistrate for over two decades.

In September 1854, at the age of 16, Maynard entered the Stamford Seminary, where he prepared for college. In 1858, he matriculated at Amherst College, where he was a member of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity and Phi Beta Kappa. Maynard was graduated from Amherst with high honors and as valedictorian in 1862, taking prizes for Greek and extemporaneous speech.

In his valedictory address, entitled “The English Constitution,” Maynard traced the development of England’s legal tradition from the Thirteenth Century. He singled out for praise both Magna Carta’s role as the “corner-stone of English liberty” and, notwithstanding the at-times despotic character of his reign, Henry VIII’s apparent teaching that “might is as essential as right, and that power is one of the conditions of justice” (Amherst College, Alumni Biographical Files). Maynard then identified that “strong arm of royal authority” as “the sentinel of English liberty” (id.). Turning from this curious embrace of monarchical absolutism, Maynard praised the Glorious Revolution of 1688 as ushering in a new epoch of British political development, one characterized by freedom, stability, and the rule of law.

After leaving Amherst, Maynard studied law with William Murray and, in November 1863, he was admitted to the bar at Binghamton. From 1863-1865, he practiced law in Delhi. In 1865, Maynard settled in Stamford, in Delaware County, and formed a law partnership with his cousin, F.R. Gilbert. Shortly thereafter, Maynard was elected Supervisor of the Town. In this capacity, he was instrumental in securing the incorporation of the Village of Stamford by special act of the Legislature in 1870. Maynard then served as first president of the Village, winning unanimous reelection for ten years in succession. Continuing his career in local government, Maynard served as President of the Board of Supervisors of Delaware County in 1869 and 1870. He married Margaret Marvine on June 28, 1871.

In 1875, Maynard won election to the State Assembly, where he served from 1876 to 1877. In 1877, he was elected Judge and Surrogate of Delaware County, for an eight-year term. Maynard grew in prominence and in 1883 he was nominated to run on the Democratic ticket for Secretary of State of New York. Here, Maynard suffered his first political setback, losing to the Republican incumbent Joseph Carr by 18,583 votes. Contemporary observers attributed Maynard’s loss to his support for temperance measures while in the Assembly, a position that alienated much of the statewide Democratic base. Maynard’s was the deciding vote against one bill that would have abolished the requirement that bar owners maintain in their homes at least three beds to let.

In January 1884, Maynard was appointed First Deputy Attorney General of the State under Attorney General Denis O’Brien, who would serve on the Court of Appeals from 1890 to 1907. Maynard resigned after less than a year in that post to become Second Comptroller of the United States Treasury under President Grover Cleveland. In 1887, when Charles S. Fairchild replaced Daniel Manning as Secretary of the Treasury, Maynard was made Assistant Secretary. In this capacity, he oversaw the Customs Service, the Internal Revenue Service and numerous other agencies. He held that position until the end of Cleveland’s first term in 1889.

On May 22, 1889, Governor David B. Hill appointed Maynard to a committee charged with revising the general laws of the State. Maynard also returned to his former position as Deputy Attorney General of New York. His tenure in this second post indelibly colored the remainder of his public life.

In the Fall of 1891, control of the State Senate hinged on four seats, including the Fifteenth Senate District, in Dutchess County. The stakes were high. In 1892, the Legislature was scheduled to take up the issue of reapportionment. Both parties scrambled for any tactical advantage, and the Democrats identified what they claimed was a fatal irregularity: a number of Republican ballots from Dutchess County had ink marks on their edges. Democratic canvassers insisted that the marks rendered the ballots defective and rejected them accordingly. The Republicans challenged this determination. Nevertheless, the County Board of Canvassers generated a set of returns favoring Edward B. Osborne, the Democrat. Storm Emans who, as the Republican County Clerk, served as ex officio Secretary of the Board of Canvassers, refused to authenticate this set of returns. The Democrats appointed John J. Mylod as Secretary pro tem of the board, and he certified the returns favoring Osborne. Emans, meanwhile, certified his own set of returns, favoring Osborne’s Republican opponent, and forwarded them to Albany.

In the ensuing litigation, Maynard represented the Democrats. Reduced to its essentials, the election controversy concerned whether the “Mylod” (i.e., Democratic) or “Emans” (i.e., Republican) returns should be canvassed. The Court of Appeals proffered its resolution on December 29, 1891 in People ex rel Daley v. Rice (129 NY 449 [1891]). In Daley, the Court ruled in favor of the Republicans, holding that, while the Mylod returns were technically proper on their face, the Democrats neither denied nor contradicted Republican allegations that the Dutchess County Board of Elections had “illegally canvassed the result of the returns” (id. at 460). The Court concluded that, as the Mylod returns “contained the result of an illegal and erroneous canvass . . . which thereby would alter the results of an election, the court should not permit it to be canvassed” (id.).

The decision became immediate dead letter. On December 29, 1891, the same day the Court handed down Daley, the State Board of Canvassers met and, with Maynard in attendance, canvassed the Mylod return, giving the Democrats a pivotal Senate seat. The Emans return was, it seems, nowhere to be found. Maynard said nothing. Given that he was responsible for the physical removal of the Emans return from the State Comptroller’s office, perhaps it would have been awkward for him to speak up.

The New York Times explained how Maynard — as counsel for the Democrats — intercepted the Emans return:

Justice Barnard granted a peremptory mandamus ordering the county canvassers to count the rejected ballots and transmit the corrected returns to Albany. Meanwhile, Gov. Hill had removed from office the Republican County Clerk because he had refused to transmit the returns as the Democrats wanted them, and appointed a Democratic County Clerk, and the ‘Mylod’ returns were made up. Emans, the Republican County Clerk, who had been removed during the litigation, which was very complicated, mailed the corrected returns to Albany. He, however, had been enjoined by an order of the court from doing so, and he hurried to Albany and called on Maynard and requested that the returns be given back to him, but they had disappeared, and when the State Board of Canvassers met the ‘Mylod’ returns were canvassed, and [the Democratic candidate Edward B.] Osborne was declared elected, giving the State Senate to the Democrats. (Ex-Judge Maynard Dead, NY Times, June 13, 1896, at 1).

In a speech to the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, James C. Carter gave a similar account of the allegations against Maynard:

There were certain election returns forwarded by the County Clerk . . . to three offices, one of them to the office of the Controller. These returns . . . were lawful returns. . . . While they were in the office of the Controller, it appears that Deputy Attorney General Isaac H. Maynard took those returns from that office without official authority. . . . It is also part of the fact, and it tends to give it a great importance, to furnish in the mind of every one a motive, that this removal of the returns enabled another return, which has been adjudged to be illegal, to be canvassed by the Board of State Canvassers, and led to the declaration that a candidate was elected in the place of another, who, it would appear, would otherwise have been elected (To Investigate Maynard, NY Times, March 9, 1892, at 1).

In January 1892, following the canvassing of the “Mylod” returns and the Democratic electoral victory, Maynard was appointed by Governor Roswell P. Flower, a Democrat, to fill a vacancy as Associate Judge on the New York Court of Appeals left by the elevation of Robert Earl to Chief Judge. His appointment aroused immediate indignation. The New York Times characterized it as a quid pro quo for Maynard’s purloining of the Emans returns: “Maynard was simply [Governor] Hill’s tool in these scandalous operations, and his promotion to the bench of the court of last resort as a reward for services to the Democratic Party must give a shock to every lawyer and citizen who believes in maintaining the purity of elections and integrity of the bench” (Maynard Gets His Pay, NY Times, January 20, 1892, at 1). In March 1892, the Legislature commenced an investigation and the Association of the Bar of the City of New York formed a nine-member committee, which included Elihu Root, William B. Hornblower, and Frederic B. Coudert, to conduct its own inquiry.

On March 16, 1892, Maynard responded to the controversy with a 19-page open letter addressed to Robert Earl, Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals.1 Maynard first stated that he had been retained by the State Board of Canvassers in a private, not official capacity. He then argued that the parties in the Dutchess County litigation had stipulated to submit their controversy — i.e., whether Mylod, as Secretary pro tem of the Dutchess County Board of Canvassers, had properly authenticated the pro-Democratic election returns — to the courts and, ultimately, the Court of Appeals for resolution. Maynard further argued that, by forwarding an amended set of returns to the Governor, Secretary of State, and Comptroller, Emans had violated this stipulation, along with two judicially imposed stays. Maynard also reported that, on the morning of December 22, 1891, Emans had called on him in Albany, explained that Republican officials had intimidated him into forwarding the new set of returns, and told Maynard that he wished to rectify his mistake. Acting, he claimed, at Emans’s behest, Maynard recovered the returns from the Comptroller’s office and restored them to Emans, who, meanwhile, had recovered the returns he had forwarded to the Governor and Secretary of State.

Maynard also defended himself against the charge that he should have alerted the State Board of Canvassers to the missing Emans returns, especially after the Court of Appeals handed down its decision in Daley:

I was present as a spectator . . . at the public meeting of the Board. . . . The inquiry was addressed to members of the Board, and not to me, and I had no right to say anything upon the subject. But counsel knew, if they knew anything about the history of the case, that the [Emans] return had been sent back eight days before, and was not then in the possession of any member of the Board.

Paying short shrift to the Board’s brazen dereliction of the Court’s holding in Daley, Maynard then suggested that the Republicans, if they felt aggrieved, should have sought a mandamus to “compel the State officers to receive the [Emans] returns; and the whole question determined, as to whether, under the facts as they then existed, it was their duty to receive and retain them.”

As anemic as this defense may appear, Maynard’s allies in the Legislature rode to his rescue on April 19, 1892. The Legislature issued two reports, one authored by the Democratic majority, the other by the Republican minority. The Democratic report, which the Legislature’s Democratic majority subsequently adopted, cleared Maynard and labeled the controversy a Republican conspiracy. Emans’s initial decision to forward the amended returns to the Secretary of State and Comptroller were, the Democrats found, illegal and in violation of two injunctive orders from Supreme Court. In intercepting the returns at the Comptroller’s office and returning them to Emans, Maynard, the majority report determined, was acting with the full authority of the Comptroller and in accordance with Supreme Court’s decrees.

By contrast, the Republican members of the Assembly and Senate Judiciary committees condemned both Maynard’s conduct during the canvassing as well as the investigation undertaken by their colleagues in the majority.2 They argued that, when Maynard took the returns from the Comptroller’s office, he deprived the State Board of Canvassers of the true election results and committed a crime in unlawfully removing public documents without authority.

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York also returned its report, declaring Maynard unfit for the judiciary. Because Maynard was not on the Court when he committed his offense, the committee concluded, impeachment did not lie. Nevertheless, the report urged the Legislature to remove Maynard by joint resolution. The Albany Law Journal praised the report and its recommendations: “In our judgment, this document deserves, indeed, demands, prompt, serious and unpartisan attention of the Legislature. . . . The charges are so weighty and so closely concern the propriety of his conduct as a lawyer and his fitness to occupy a place on the bench as entirely to remove the discussion from the region of politics” (45 Alb LJ 287 [1892])3.

The Legislature disregarded the Association’s report. Notwithstanding the controversy dogging Maynard, in December 1892, Governor Flower reappointed him to another one-year term as Associate Judge. He did so over the protests of many in the press and at the bar. For this second term, Maynard filled the vacancy left by Charles Andrews, who was promoted to Chief Judge. Maynard remained on the bench through December 31, 1893.

The scandal surrounding his appointment aside, Maynard was an active and productive member of the Court of Appeals during his short time on the tribunal. The Albany Law Journal noted that Maynard’s “relations with the other members of the court have apparently been most cordial and friendly, and there has been nothing to indicate that the judges occupying the bench regard his conduct . . . as in any way derogatory to his character or affecting his standing as a member of the bench” (48 Alb LJ 341 [1893]). Maynard’s opinions were heavily civil in their complexion, with criminal appeals representing only a modest portion of his judicial work. Although none of his writings are of surpassing prominence, they nevertheless evidence a thoughtful character. By his opinion in Manhattan Life Insurance Co v. Forty second Street and Grand Street Ferry Railroad Co. (139 NY 146 [1893]), the Court held that a railroad company was not liable for a loan secured by its president by pledging as collateral corporate stock certificates when the president lacked the authority — actual or apparent — to issue certificates of stock (but cf Fifth Avenue Bank of New York v. Forty second Street and Grand Street Ferry Railroad Company, 137 NY 231 [1893] [holding, in an opinion by Judge Maynard, that a corporation was liable for a corporate officer’s forgery of a stock certificate to secure a loan when the issuance of stock certificates was within the scope of his authority and course of his employment]). In Parker v. Marco (136 NY 585, 589 [1893]), he affirmed the principle that an out-of-state witness called to New York to attend court “in an action to which he is a party or in which he is to be sworn as a witness” is exempt from service of process while in the State. In Condict v. Cowdrey (139 NY 273 [1893]), he determined that a real estate broker was not entitled to a commission when, through no fault of the broker, the buyer was unable to secure marketable title.

In 1893, Maynard ran for a full term on the Court of Appeals, on the Democratic ticket. Citing his conduct during the 1891 election, the Association of the Bar of the City of New York denounced his nomination, with only three members dissenting from the resolution. Likewise, the New York Tribune commented “[i]t is not easy to reconcile such a nomination as that of Maynard with the belief that the people are intelligent, honest, anxious to get justice done and fit for the responsibilities of self-government” (The Case of Judge Maynard, NY Tribune, October 8, 1893). When it flocked to the polls, the electorate manifested a similar sentiment: Maynard’s Republican opponent, Edward T. Bartlett beat him by over 100,000 votes statewide, a staggering margin at the time. The degree of popular indignation aroused by Maynard was so great that he dragged down the rest of the Democratic ticket, leaving the Republicans with control of both houses of the Legislature and the 1894 constitutional convention. Although it gave Democrats a temporary majority in the Legislature, the 1891 election scandal ultimately precipitated a backlash against bossism and Tammany. It also dealt a severe blow to the presidential aspirations of Maynard’s longtime patron David Hill, who purportedly contrived the Democrats’ theft of the contested Senate seats, and resulted in 16 years of Republican control over State government.

Having lost election to a full term, Maynard left the Court at the end of December 1893. Hill, now a member of the United States Senate, recommended him for appointment to the Supreme Court. President Cleveland ignored the suggestion. Maynard’s defeat in 1893 thus marked the end of his public life, and he returned to the private practice of law, as a senior member of the firm of Maynard, Gilbert & Cone. He died of a heart attack on June 13, 1896, in his room at the Kenmare Hotel in Albany, and is buried in Delhi.

Notwithstanding the brooding legal and ethical cloud that glowered over him, Maynard had defenders to the last. In their obituary, the editors of the Albany Law Journal described him as:

a man of rare legal ability in his chosen profession. As judge of the Court of Appeals, he was regarded as one of the strongest members of the court, and his opinions were marked by great legal learning, and by a clear and precise application of the facts involved. For the past few years, most his practice was before the Court of Appeals, where his masterly arguments were generally marked by success. Judge Maynard was particularly thorough in practice, and his briefs, as well as opinions, were marked by logical argument and precise learning. The bar of this city and State have lost a most learned member and faithful student (53 Alb LJ 385 [1896]).

It is regrettable that a man of such undeniable talent and acumen as Isaac Maynard would find his life and reputation so enmeshed in controversy.

Progeny

Isaac and Margaret Marvine Maynard had one daughter, Frances Maynard. She married David Ford, with whom she had three children, including the grandmother of John Charles Harris of Dallas, Texas, President and Chief Executive Officer of Viseon, a communications company in Dallas. Judge Maynard’s other living descendants are David Ford, of Lincoln, Massachusetts, married to Mary Gillingham. They are the parents of David Fairbanks Ford and Warren Ford.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Amherst College, Alumni Biographical Files, Maynard, Isaac, H.

Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, at 140-144 (1985).

Current Topics, 45 Alb LJ at 248, 287, 308, 367-368 (1892).

—-, 48 Alb LJ 341 (1893).

—-, 53 Alb LJ 385 (1896).

Democrats Will Cut Cook, NY Times, October 30, 1885, at 5.

Dragged Down by Maynard, NY Times, November 8, 1893, at 1.

Ex-Judge Maynard Dead, NY Times, July 13, 1896, at 1.

Frank, Supreme Court Appointments: II, 1941 Wis L Rev 343, 371.

Governor Flower’s Curious Action, NY Times, December 23, 1892, at 1.

Isaac Horton Maynard, The Leading Citizens of Delaware County, www.dcynhistory.org/books/

brevie12.html, last accessed July 7, 2005.

Judge Maynard’s letter in regard to the contested senatorial election cases: to Hon. Robert Earl . . . and Hon. David L. Follett of March 16, 1892, www.galenet.galegroup.com, last accessed August 1, 2005.

Judge Maynard’s Record, NY Times, August 28, 1891.

Kurland, The Appointment and Disappointment of Supreme Court Justices, 1972 Law & Soc. Order 183, 210 (1972).

MacAdam, History of the bench and bar of New York, at 202 (1897).

Maynard Gets His Pay, NY Times, January 20, 1892, at 1.

Now Let Maynard Squirm, NY Times, March 25, 1892, at 1.

Not Through with Maynard Yet, NY Times, December 14, 1892, at 5.

O’Brien, The Nine Rejected Men, 19 Baylor L. Rev. 14, 15 (1967).

Rogers, A Desperate Chance, Harper’s Weekly, October 1813, 1894. at 1.

Storm Emans’s Backers, NY Times, February 2, 1892, at 1.

The Case of Judge Maynard, NY Tribune, October 8, 1893.

The Expected Whitewash, NY Times, April 19, 1892, at 1.

To Investigate Maynard, NY Times, March 9, 1892, at 1.

To Move Against Maynard, NY Times, February 22, 1892, at 3.

Verdict on Maynard Stands, NY Times, October 11, 1892, at 1.

Published Writings

To date, we are not aware of any published writings by Judge Maynard.

Endnotes

- Judge Maynard’s open letter is available at http://galenet.galegroup.com.

- This sentiment enjoyed a great degree of resonance. The Albany Law Journal declared that the Democrats’ “so-called” investigation a “one-sided inquiry” (45 Alb LJ 367 [1892]). The “partisan character of the proceedings was so evident and undisguised that the award will exercise no influence whatever with men who have any independence of party. . . . The legislative committee not only refused to allow Judge Maynard’s accusers to produce any evidence, but undertook to conduct the investigation secretly at the last. Fair minded men will regret that an opportunity was not given to produce witnesses offered to contradict some assertions in Judge Maynard’s letter, and that the Judge himself did not improve the opportunity afforded him of putting himself under oath. . . and that an opportunity was not afforded his accusers of cross-examining him” (id.). The Albany Law Journal further condemned Maynard’s fitness for the bench: “Nor shall we shrink from expressing the opinion that the man who entertains such notions of professional honor and is held in such subservience by party ties, is not a fit person to sit in the highest court of this State, to be empowered possibly to dictate the result of future elections, and certainly to pass upon the conflicting private claims of suitors who may be members of the opposing political parties” (id.).

- See also 45 Alb LJ 248 (1892).