Description

January 2014

A New World: The Charter of 1621

We may trace our presence in New York from one of the first governing documents marking the settlement of New Netherland, an area ranging from the Delaware to the Connecticut Rivers, as a Dutch Colony: the 1621 charter of the Dutch West India Company.

In the early 1600s, Dutch merchants had been sailing the Atlantic, bringing back sugar from Brazil and other places. The Dutch fishing industry needed salt, and Dutch ships returned with salt from the Cape Verde Islands and other locations.

For the Dutch, Spain was an economic and military rival, and in 1621 — almost immediately after hostilities with Spain resumed following the Twelve Years’ Truce — the Dutch States General issued the patent for the West India Company. To create an Atlantic empire, the Dutch would have to wage war against Spain and Portugal, and so trade and war were allies in the formation of the Company. Because the Company felt that the “discovery” of the New Netherland area was not enough to lay claim, it sent colonists to populate the area. The date of the settlement is inexact but it was around 1623 or 1624. (See generally Jaap Jacobs, New Netherland, A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth Century America 37-44, 2005)

And so it began.

Images:

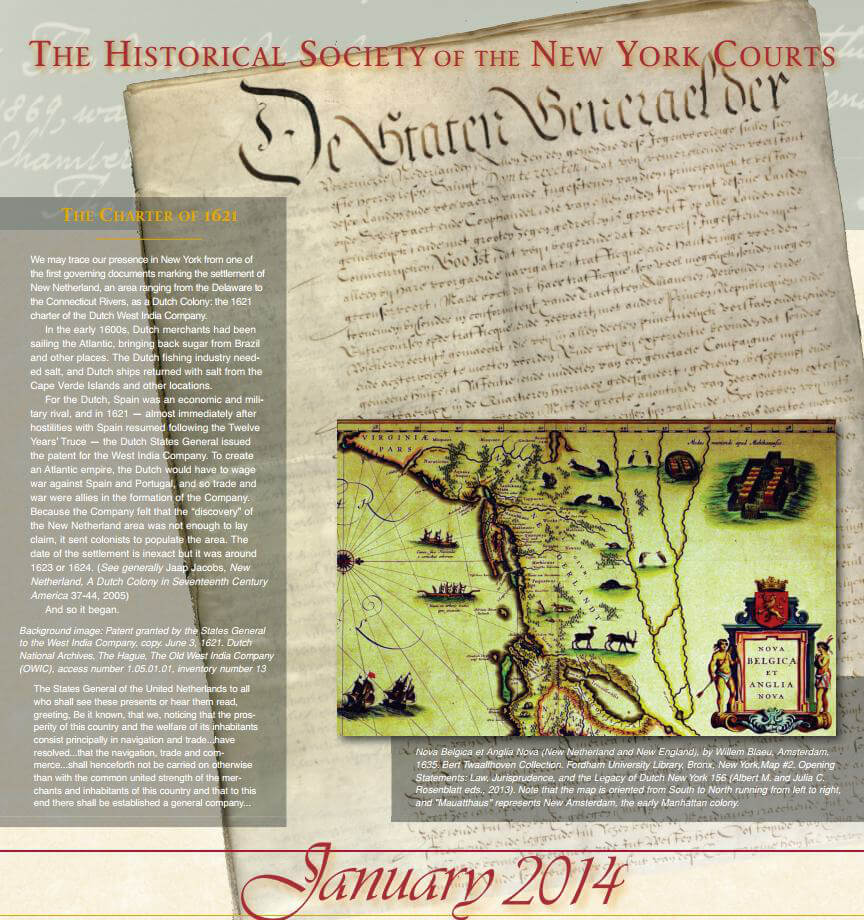

Nova Belgica et Anglia Nova (New Netherland and New England), by Willem Blaeu, Amsterdam, 1635. Bert Twaalfhoven Collection. Fordham University Library, Bronx, New York, Map #2. Opening Statements: Law, Jurisprudence, and the Legacy of Dutch New York 156 (Albert M. and Julia C. Rosenblatt eds., 2013)

Patent granted by the States General to the West India Company, copy. June 3, 1621. Dutch National Archives, The Hague, The Old West India Company (OWIC), access number 1.05.01.01, inventory number 13

The States General of the United Netherlands to all who shall see these presents or hear them read, greeting, Be it known, that we, noticing that the prosperity of this country and the welfare of its inhabitants consist principally in navigation and trade…have resolved…that the navigation, trade and commerce…shall henceforth not be carried on otherwise than with the common united strength of the merchants and inhabitants of this country and that to this end there shall be established a general company…

February 2014

The Governing Documents Under Dutch Rule

In the early 1600s some 30 Walloon families arrived in New Netherland as settlers under a system of administration and justice that the Dutch West India Company (WIC) designed. Three documents reveal the company’s vision for its place in the new world: the Provisionele Ordere [Provisional Regulations] of March 30, 1624 and the January and April 1625 Instructions to the Colony’s Director Willem Verhulst.

Article twenty of the April 1625 Further Instructions from the WIC to Verhulst provided that the ordinances of Holland and Zeeland would govern “the administration of justice, in matters concerning marriages, the settlements of estates, and contracts.”

The Provisional Regulations contain some 21 provisions, of which two are of particular interest, insofar as one deals with worship and freedom of conscience:

[The colonists] shall within their territory practice no other form of divine worship than that of the Reformed religion as at present practiced here in this country and thus by their Christian life and conduct seek to draw the Indians and other blind people to the knowledge of God and His Word, without however persecuting any one on account of his faith, but leaving to every one the freedom of his conscience.

The other deals with their attitude toward natives:

They shall take especial care, whether in trading or in other matters, faithfully to fulfill their promises to the Indians or other neighbors and not to give them any offense without cause as regards their persons, wives, or property, on pain of being rigorously punished therefor.

Images:

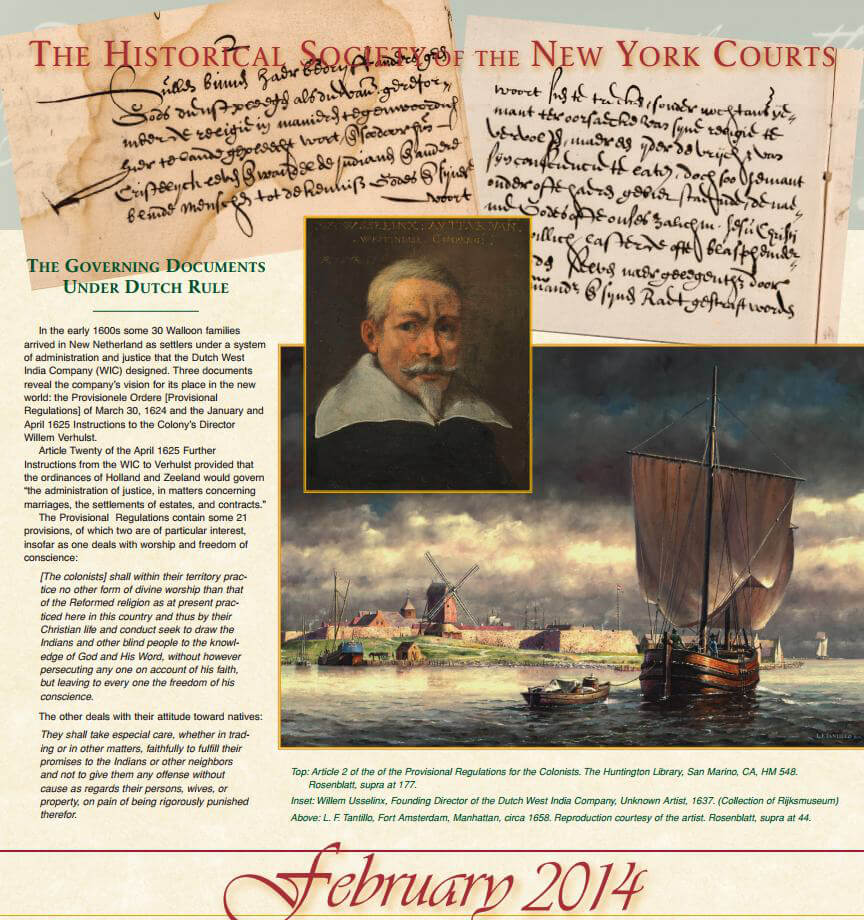

Article 2 of the of the Provisional Regulations for the Colonists. The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, HM 548. Rosenblatt, supra at 177.

Willem Usselinx, Founding Director of the Dutch West India Company, Unknown Artist, 1637. (Collection of Rijksmuseum)

F. Tantillo, Fort Amsterdam, Manhattan, circa 1658. Reproduction courtesy of the artist. Rosenblatt, supra at 44.

March 2014

A Municipal Government and a Court of Justice in New Amsterdam, 1653

New Amsterdam, located on the southern tip of Manhattan, was settled long before 1653, but that year marks the charter that founded a municipal government for New Amsterdam. After receiving permission from the WIC directors in Holland, Petrus Stuyvesant and his council established a court of justice in New Amsterdam, the installation taking place on February 2, 1653. The burgemeesters were responsible for administrative tasks and also had the duty, along with the schepenen, to administer justice. Their sentencing powers were based on the laws of Patria and as far as possible in accordance with the laws of Amsterdam (Netherlands) and of the local Director General and Council. Burgemeesters and schepenen were responsible for maintaining public works, such as roads and canals, sanitation, fire control, and defense.

Even before the court of burgemeesters and schepenen on Manhatten in 1653 there were local courts (small benches of justice) in several villages, starting in Middelburgh (Newtown) in 1642. Most of these courts were in Long Island, populated by English colonists. Breuckelen (Brooklyn), in 1646, was the first Dutch village to gain a court.

The City of New Amsterdam government grew, to include a body of officials such as secretary, receiver, and treasurer, as well as a body of lower officials such as court messenger, jailer, dog catcher, town crier, harbormaster, and weigh house hands. Of course ultimate authority rested with the WIC in the Netherlands. (See generally, Jaap Jacobs, The Colony of New Netherland, A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America 87-96, 2009)

Images:

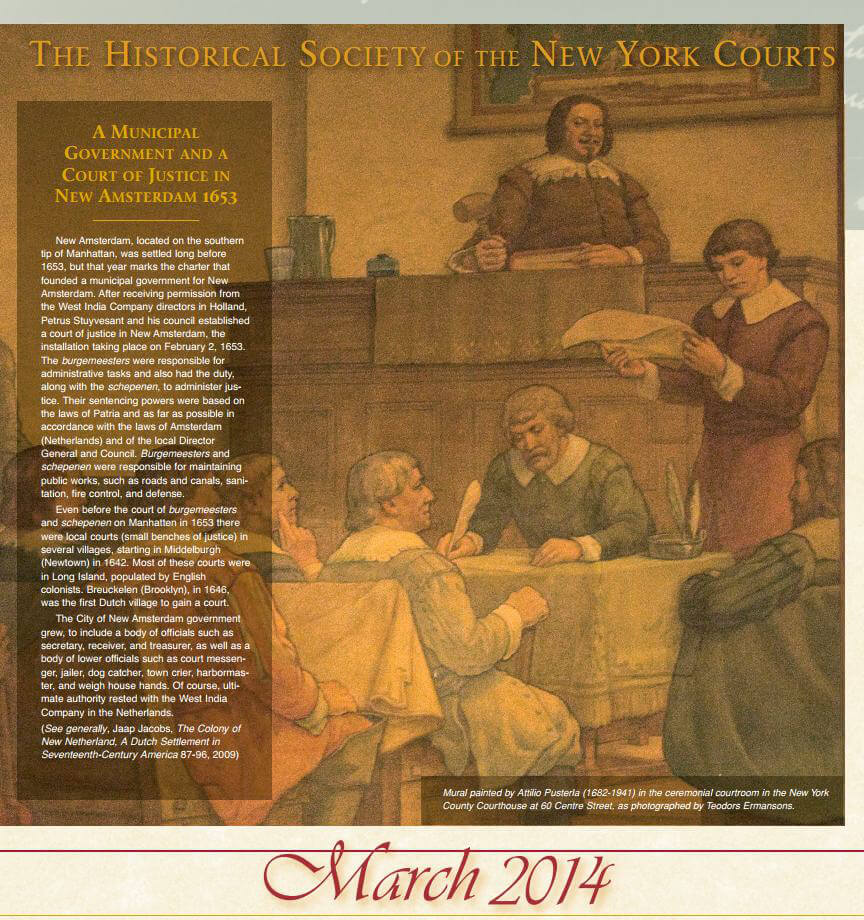

Mural painted by Attilio Pusterla (1682-1941) in the ceremonial courtroom in the New York County Courthouse at 60 Centre Street, as photographed by Teodors Ermansons

April 2014

English Rule: The Duke’s Laws of 1665

In 1664 New Netherland fell to a British naval force led by Captain Richard Nicolls. The 23 Articles of Capitulation, by which the English took New Netherland, dealt with administration, justice, and law. Charles II was on the English throne, as his brother, James Stuart (the Duke of York and later King James II of England) had urged an aggressive policy toward the Dutch Republic. After the conquest, England would command the east coast of America from Nova Scotia to the Carolinas as New Netherland and New Amsterdam became New York.

The Dutch briefly recaptured the territory in 1673 and renamed New York New Orange. The interim Dutch rule lasted 15 months, and in 1674 the English regained the Colony under the Treaty of Westminster.

The Duke’s Laws of 1665, written originally only for New York’s English communities on Long Island, gradually expanded province-wide. These laws covered a multitude of provisions — civil, criminal, and administrative. They covered appeals, record registration, capital punishment, worship, conveyances, defamation, fees, fires, Indians, military concerns, and arbitration, not to mention wolves and pipe staves.

David W. Voorhees notes (English Law through Dutch Eyes: The Leislerian Understanding of the English Legal System in New York, in the Society’s new publication Opening Statements: Law, Jurisprudence, and the Legacy of Dutch New York 207-228 (2013) that under English rule Dutch influence is most evident in New Yorkers’ communal resistance to centralizing tendencies in imperial authority. Also, that some of the traditional liberties that the Dutch brought to the New World were incorporated into the complexities they introduced, as where special interest groups coalesced in Dutch fashion to pursue common goals.

Images:

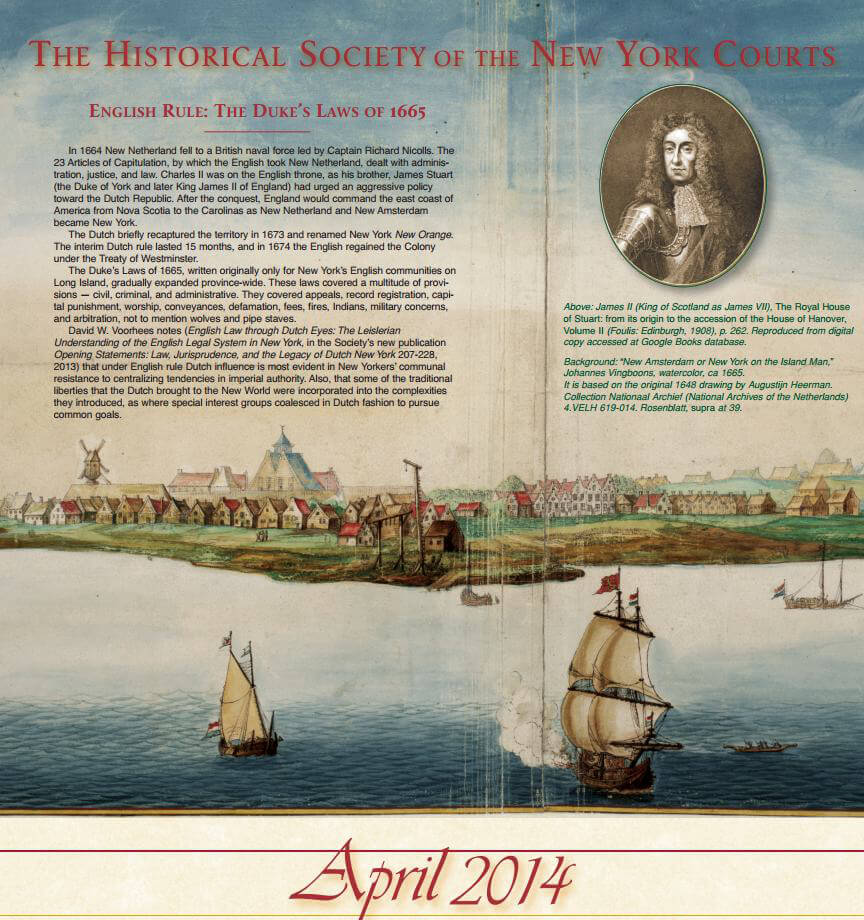

James II (King of Scotland as James VII), The Royal House of Stuart: from its origin to the accession of the House of Hanover, Volume II (Foulis: Edinburgh, 1908), p. 262. Reproduced from digital copy accessed at Google Books database

“New Amsterdam or New York on the Island Man,” Johannes Vingboons, watercolor, ca 1665. It is based on the original 1648 drawing by Augustijn Heerman. Collection Nationaal Archief (National Archives of the Netherlands) 4.VELH 619-014. Rosenblatt, supra at 39.

May 2014

The Creation of the State Supreme Court, 1691

What culminated in 1776 had long been stirring, and revealed itself in ways that included colonial pressure leading to the creation of an Assembly in 1683 — with some delegates chosen by direct vote — and by the Charter of Liberties of that year.

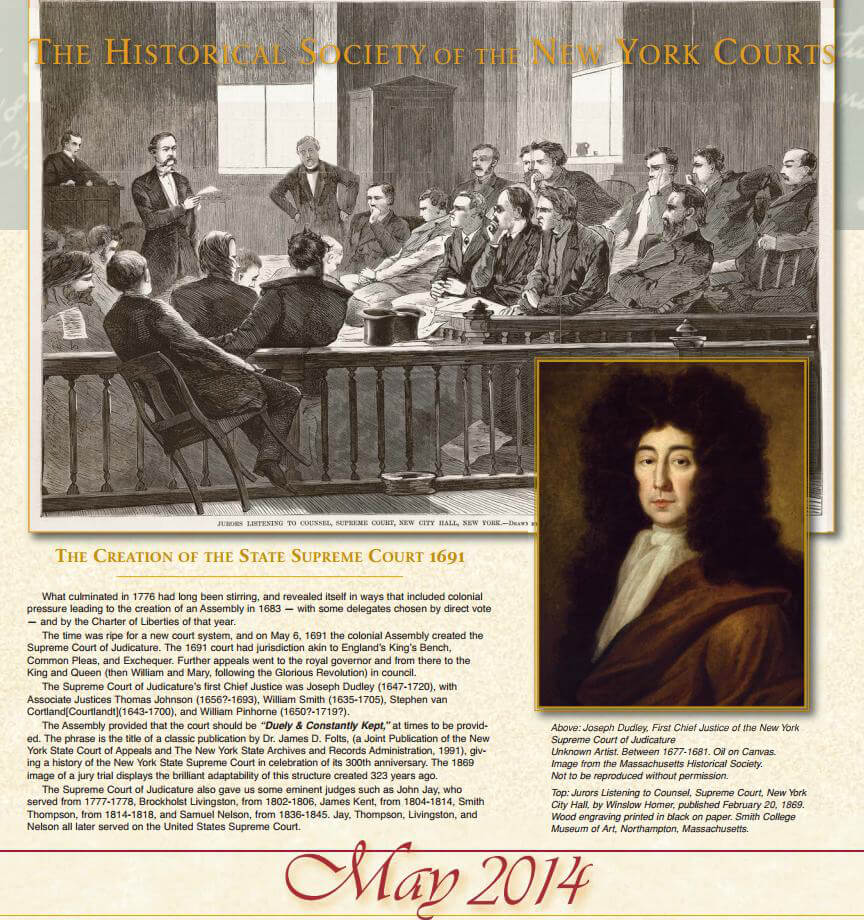

The time was ripe for a new court system, and on May 6, 1691 the colonial Assembly created the Supreme Court of Judicature. The 1691 court had jurisdiction akin to England’s King’s Bench, Common Pleas, and Exchequer. Further appeals went to the royal governor and from there to the King and Queen (then William and Mary, following the Glorious Revolution) in council.

The Supreme Court of Judicature’s first Chief Justice was Joseph Dudley (1647-1720), with Associate Justices Thomas Johnson (1656?-1693), William Smith (1635- 1705), Stephen van Cortland[Courtlandt](1643-1700), and William Pinhorne (1650?-1719?).

The Assembly provided that the court should be “Duely & Constantly Kept,” at times to be provided. The phrase is the title of a classic publication by Dr. James D. Folts, (a Joint Publication of the New York State Court of Appeals and The New York State Archives and Records Administration, 1991), giving a history of the New York State Supreme Court in celebration of its 300th anniversary.

The Supreme Court of Judicature also gave us some eminent judges such as John Jay, who served from 1777-1778, Brockholst Livingston, from 1802-1806, James Kent, from 1804-1814, Smith Thompson, from 1814-1818, and Samuel Nelson, from 1836-1845.. Jay, Thompson, Livingston, and Nelson all later served on the United States Supreme Court.

Images:

Joseph Dudley, First Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court of Judicature. Unknown Artist. Between 1677-1681. Oil on Canvas. Image from the Massachusetts Historical Society. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Jurors Listening to Counsel, Supreme Court, New York City Hall, by Winslow Homer, published February 20, 1869. Wood engraving printed in black on paper. Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts.

June 2014

New York’s First Constitution, 1777

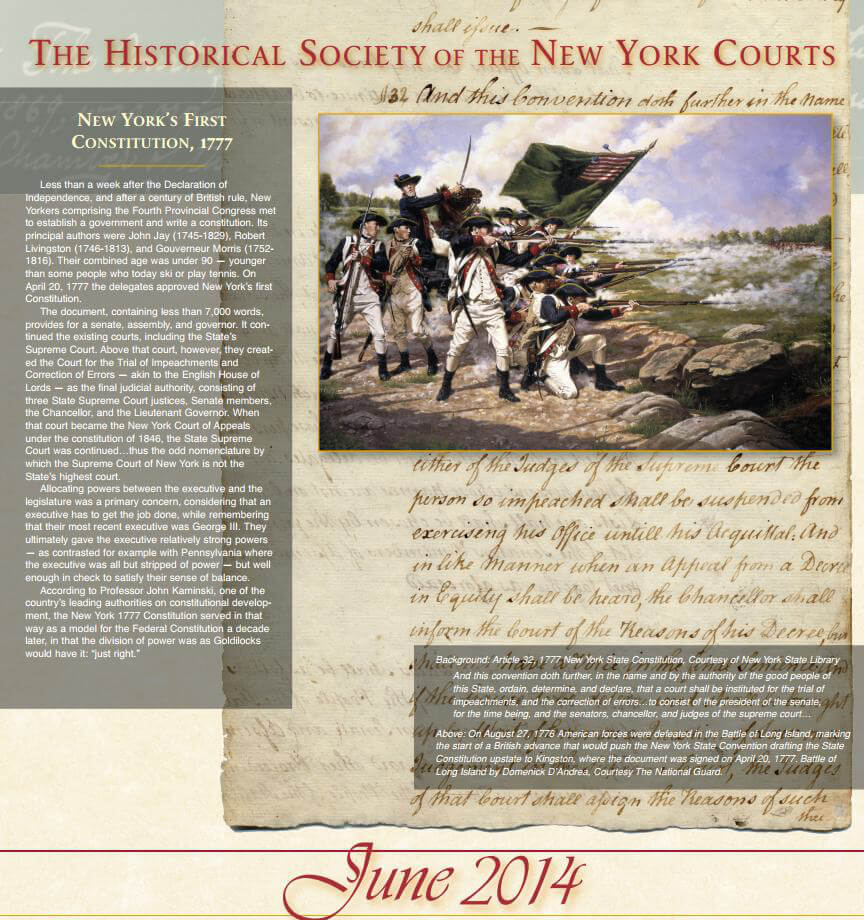

Less than a week after the Declaration of Independence, and after a century of British rule, New Yorkers comprising the Fourth Provincial Congress met to establish a government and write a constitution. Its principal authors were John Jay (1745-1829), Robert Livingston (1746-1813), and Gouverneur Morris (1752-1816). Their combined age was under 90 — younger than some people who today ski or play tennis. On April 20, 1777 the delegates approved New York’s first Constitution.

The document, containing less than 7,000 words, provides for a senate, assembly, and governor. It continued the existing courts, including the State’s Supreme Court. Above that court, however, they created the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and Correction of Errors — akin to the English House of Lords — as the final judicial authority, consisting of three State Supreme Court justices, Senate members, the Chancellor, and the Lieutenant Governor. When that court became the New York Court of Appeals under the constitution of 1846, the State Supreme Court was continued…thus the odd nomenclature by which the Supreme Court of New York is not the State’s highest court.

Allocating powers between the executive and the legislature was a primary concern, considering that an executive has to get the job done, while remembering that their most recent executive was George III. They ultimately gave the executive relatively strong powers — as contrasted for example with Pennsylvania where the executive was all but stripped of power — but well enough in check to satisfy their sense of balance.

According to Professor John Kaminski, one of the country’s leading authorities on constitutional development, the New York 1777 constitution served in that way as a model for the federal constitution a decade later, in that the division of power was as Goldilocks would have it: “just right.”

Images:

Article 32, 1777 New York State Constitution, Courtesy of New York State Library

And this convention doth further, in the name and by the authority of the good people of this State, ordain, determine, and declare, that a court shall be instituted for the trial of impeachments, and the correction of errors…to consist of the president of the senate, for the time being, and the senators, chancellor, and judges of the supreme court…

Senate House, Kingston, Ulster County, NY. Building where the First New York State Constitution was signed. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS NY,56-KING,7–1W

On August 27, 1776 American forces were defeated in the Battle of Long Island, marking the start of a British advance that would push the New York State Convention drafting the State Constitution upstate to Kingston, where the document was signed on April 20, 1777. Battle of Long Island by Domenick D’Andrea, Courtesy The National Guard.

July 2014

Due Process in New York Leading the Way in 1787

We associate the words “due process of law” with the Fifth Amendment (1791) and Fourteenth Amendment (1868) of the U. S. Constitution. The concept goes back to Magna Carta of 1215 which in article 39 declared that:

No freeman shall be taken, or imprisoned, or disseized, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way harmed — nor will we go upon or send upon him — save by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land. (emphasis added)

The later formulation, ”due process of law” may have first appeared in an English statute during the reign of Edward III in 1354. ”No man of what state or condition he be, shall be put out of his lands or tenements nor taken, nor disinherited, nor put to death, without he be brought to answer by due process of law.” (emphasis added)

New York’s landmark usage of the phrase “due process of law” appears no less than five times in a 1787 statute — a bill of rights — passed by the New York Legislature in their tenth session, four years before the United States Constitution’s Fifth Amendment. New York’s 1787 provision guarantees:

That no citizen of this State shall be taken or imprisoned or be disseised of his or her freehold or liberties of free customs or outlawed or exiled or condemned or otherwise destroyed, but by lawful judgment of his or her peers or by due process of law. (emphasis added)

Further, the 1787 statutory bill of rights provided, among other rights, for free elections, free speech, the right of petition, and proscriptions against cruel and unusual punishments, and excessive bail. There was no mention of freedom of religion, but in New York’s Constitution of 1777 the state guaranteed that “the free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever hereafter be allowed, within this State, to all mankind…”

Images:

New York’s Bill of Rights Statute. Chapter 1, 10th Session of the New York State Legislature, 1787. New York State Archives, Enrolled Acts of the State Legislature, 1778-2010, (N-Ar)13036

View of New York. D.T. Valentine, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, for the Year of 1851, p. 271 (New York: The Council, 1851)

August2014

New York’s Abolition of Slavery, 1799-1827

In 1799 the New York State Legislature enacted a statute starting the process for the emancipation of slaves in New York. The statute (L.1799, ch. 62) provided that a child born to a slave after July 4, 1799 would be considered free. The children would, however, continue to serve the mother’s owner until age 28, for a male, or 25, for a female. The Legislature passed other statutes allowing for voluntary manumission, and in 1817 (ch.137) provided that everyone born before July 4, 1799 would become free by July 4, 1827.

In 1629, the Dutch West India Company was charged with supplying New Netherland with “as many Blacks as they conveniently can.” (See Van Rensselaer Bowier Manuscripts 163 (A.J.F. Van Laer, ed., 1908)) According to Graham Russell Hodges, Root and Branch: African Americans in New York and East Jersey 9-10 (1999), by 1630 there were 300 Europeans and a few blacks, the latter being the “core laborers.”

After Brazil fell to Portugal in 1648, the New Netherland Director and Council passed a resolution opening trade to Brazil and Angola, and authorizing the transportation of slaves into New Netherland. (1 N.Y. Col. Docs. 215). The Directors in Holland agreed, stating that when ships had completed their trade in Angola, they “may carry Negroes to your place to be employed in the cultivation of the soil.” (Laws and Ordinances of New Netherland, 1638-1674 p. 11 fn (E.B. O’Callaghan ed., Albany: Weed, Parsons, and Co., 1869))

The West India Company began to import slaves directly from Africa as authorized by an August 6, 1655 ordinance. (O’Callaghan, supra at 191) The first shipment of approximately 300 arrived that year on the Witte Paert. By 1660, New Amsterdam had become a major port for the slave trade (Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery, 2003)

Images:

First Slave Auction in New Amsterdam, 1655. Illustration by Howard Pyle, 1895. The Granger Collection, NYC.

Manumission certificate for slave named George signed by Radcliffe and Riker in New York City on April 24, 1817. New York Public Library, Slavery and Abolition Collection.

September 2014

New York’s Second Constitution, 1821

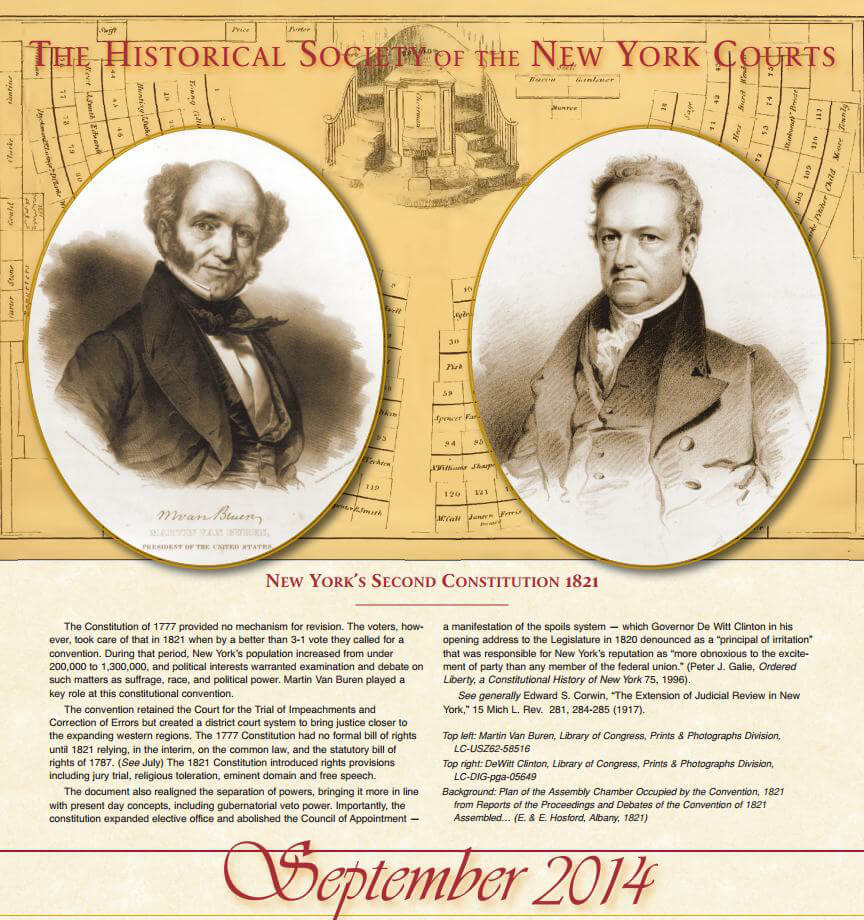

The Constitution of 1777 provided no mechanism for revision. The voters, however, took care of that in 1821 when by a better than 3-1 vote they called for a convention. During that period, New York’s population increased from under 200,000 to 1,300,000, and political interests warranted examination and debate on such matters as suffrage, race, and political power. Martin Van Buren played a key role at this constitutional convention.

The convention retained the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and Correction of Errors but created a district court system to bring justice closer to the expanding western regions. The 1777 constitution had no formal bill of rights until 1821 relying, in the interim, on the common law, and the statutory bill of rights of 1787. (See July) The 1821 constitution introduced rights provisions including jury trial, religious toleration, eminent domain and free speech.

The document also realigned the separation of powers, bringing it more in line with present day concepts, including gubernatorial veto power. Importantly, the constitution expanded elective office and abolished the Council of Appointment — a manifestation of the spoils system — which Governor De Witt Clinton in his opening address to the Legislature in 1820 denounced as a “principal of irritation” that was responsible for New York’s reputation as “more obnoxious to the excitement of party than any member of the federal union” (Peter J. Galie, Ordered Liberty, a Constitutional History of New York 75, 1996).

See generally Edward S. Corwin, “The Extension of Judicial Review in New York,” 15 Mich L. Rev. 281, 284-285 (1917).

Images:

DeWitt Clinton, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-05649

Martin Van Buren, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-58516

Plan of the Assembly Chamber Occupied by the Convention, 1821 from Reports of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1821 Assembled… (E. & E. Hosford, Albany, 1821)

October 2014

New York’s Third Constitution 1846: There Shall be a Court of Appeals

One of the main issues at the constitutional convention of 1846 was the need for judicial reform. The convention chose Judge Charles Herman Ruggles (1789-1865), a widely respected jurist, as chairman of the judiciary committee.

The delegates generally believed that the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and Correction of Errors had outlived its usefulness, and that a 37 member court, consisting in part of the entire Senate, was not the ideal tribunal to engage in judicial review.

The convention eventually agreed (Art 6 Sec 2) on a Court of Appeals consisting of eight judges, four to be elected statewide for an eight year term, and four from the class of Supreme Court Justices (elected by district) having the shortest term to serve, and who rotated in and out yearly.

This infelicitous arrangement was a recipe for instability. (See generally Judith S. Kaye and Francis Murray, There Shall be a Court of Appeals (1997); Albert M. Rosenblatt, The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals (2007).

The delegates abolished the Court of Chancery and continued the Supreme Court, giving it jurisdiction in law and equity.

The Court of Appeals was empowered to review the decisions of the State’s Supreme Court, and a question arose as to whether a former State Supreme Court Justice could review his decision when serving as a judge of the Court of Appeals. In Pierce v Delameter, 1 NY 17 (1847) Judge Bronson said yes, and affirmed his earlier ruling. But in the lesser known case of Shindler v Houston, 1 NY 261 (1848) he joined his Court of Appeals colleagues in a reversal. An 1869 constitutional amendment prohibited judges from reviewing their lower court rulings.

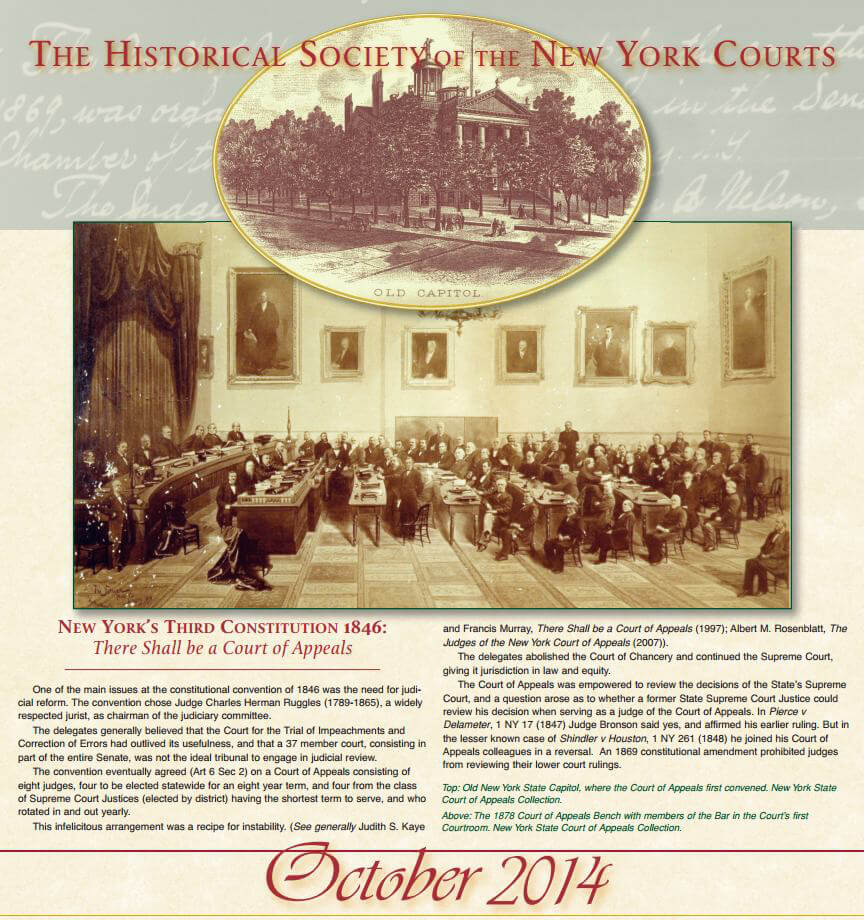

Images:

Old New York State Capitol, where the Court of Appeals first convened. New York State Court of Appeals Collection.

The 1878 Court of Appeals Bench with members of the Bar in the Court’s first Courtroom. New York State Court of Appeals Collection.

November 2014

The Judicial Article of 1869

A constitutional convention was held in 1867, between the Third and the Fourth Constitutions (1846 and 1894), but the voters rejected all except the judiciary article which became a constitutional amendment in 1869, taking effect in 1870.

The 1869 amendment made significant changes, bringing the composition and tenure of the Court of Appeals closer to what we recognize today. Under the amendment, the Court would be composed of a Chief Judge and six Associate Judges chosen by statewide vote, for a 14 year term, with mandatory retirement at 70. This November the voters will have a chance to amend the Constitution and extend the retirement age to 80. Establishing a court with consistent membership gave the court a stability and sense of continuity lacking in State Supreme Court where Justices rotated on and off the court.

Notably, the amendment took into account the political make-up of the court by providing that at the first election to follow, the voters may vote for the Chief Judge “and only four of the associate judges.” This enabled the minority party to elect at least two judges, preventing domination by one political party.

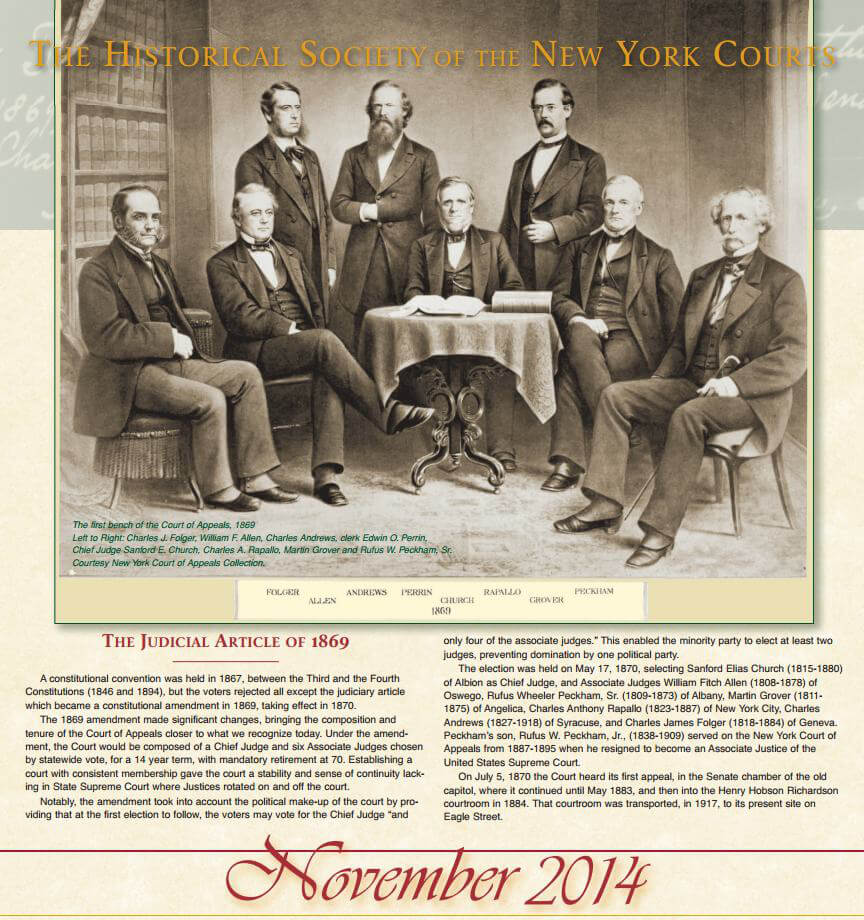

The election was held on May 17, 1870, selecting Sanford Elias Church (1815-1880) of Albion as Chief Judge, and Associate Judges William Fitch Allen (1808-1878) of Oswego, Rufus Wheeler Peckham, Sr. (1809-1873) of Albany, Martin Grover (1811-1875) of Angelica, Anthony Charles Rapallo (1823-1887) of New York City, Charles Andrews (1827-1918) of Syracuse, and Charles James Folger (1818-1844) of Geneva. Peckham’s son, Rufus W. Peckham Jr. (1838-1909) served on the New York Court of Appeals from 1887-1895 when he resigned to become an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

On July 5, 1870 the Court heard its first appeal, in the Senate chamber of the old capitol, where it continued until May 1883, and then into the Henry Hobson Richardson courtroom in 1884. That courtroom was transported, in 1917, to its present site on Eagle Street.

Images:

The first bench of the Court of Appeals, 1869. Left to Right: Charles J. Folger, William F. Allen, Charles Andrews, clerk Edwin O. Perrin, Chief Judge Sanford E. Church, Charles A. Rapallo, Martin Grover and Rufus W. Peckham, Sr. Courtesy New York Court of Appeals Collection

Artists Conception of the completed Brooklyn Bridge, which began construction in 1870. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC2-2513.

December 2014

The Fourth Constitution 1894 and the Later Amendments of 1977

In tandem with the changes under the constitutional amendment of 1869 (See November), and to tackle the Court’s abundant and growing caseload, the Legislature created the Commission on Appeals, giving it decisional authority equal to the Court of Appeals to hear cases from the pre-1870 backlog. It began hearing appeals reported in 44 NY.

Again, in 1887, and by constitutional amendment approved by the voters, the Court of Appeals was aided by a “second division” which sat from March 1889 through October 1892. Its reported cases run from 114 NY to 134 NY.

The constitutional convention of 1894 established the first state system of education in the country, and adopted a provision setting aside the Adirondack and Catskill Forest Preserves to be kept “forever wild.” (See generally Peter J. Galie, Ordered Liberty 159-187, 1996)

With respect to the judiciary, the convention created the four Appellate Divisions of the State Supreme Court, a formulation that is largely intact today.

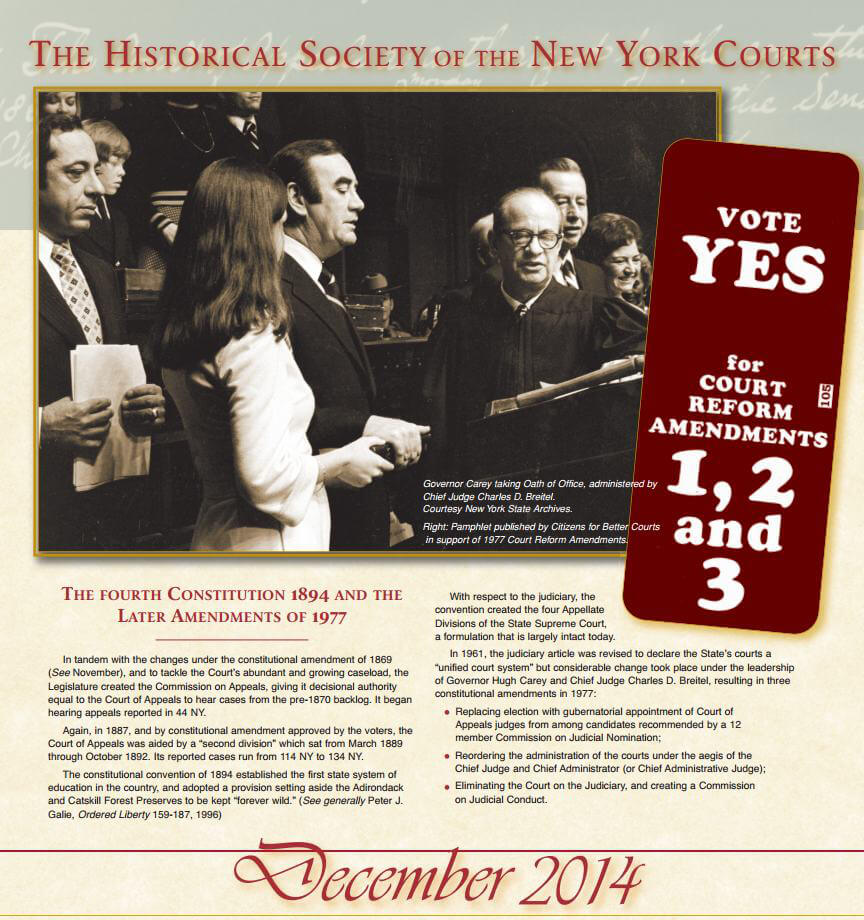

In 1961, the judiciary article was revised to declare the State’s courts a “unified court system” but considerable change took place under the leadership of Governor Hugh Carey and Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel, resulting in three constitutional amendments in 1977:

- Replacing election with gubernatorial appointment of Court of Appeals judges from among candidates recommended by a 12 member Commission on Judicial Nomination;

- Reordering the administration of the courts under the aegis of the Chief Judge and Chief Administrator (or Chief Administrative Judge).

- Eliminating the Court on the Judiciary, and creating a Commission on Judicial Conduct.

Images:

Governor Carey taking Oath of Office, administered by Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel. Courtesy New York State Archives.

Pamphlet published by Citizens for Better Courts in support of 1977 Court Reform Amendments.