Description

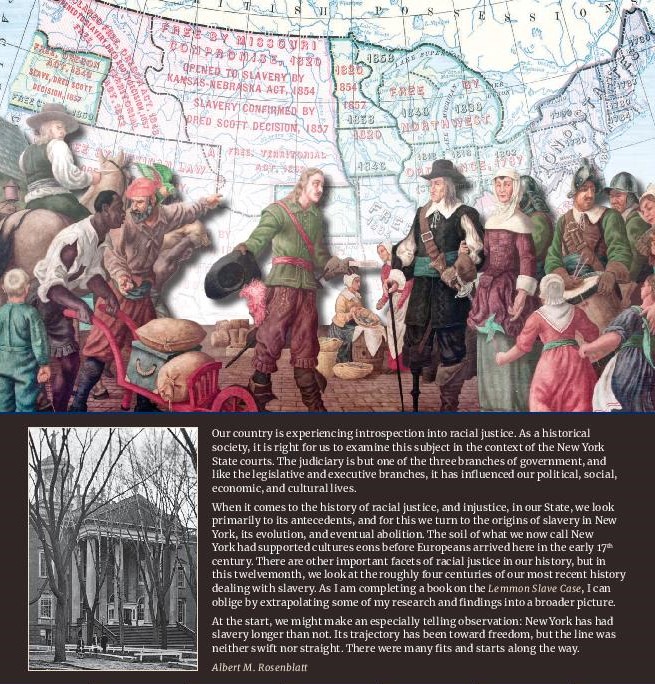

Our country is experiencing introspection into racial justice. As a historical society, it is right for us to examine this subject in the context of the New York State courts. The judiciary is but one of the three branches of government, and like the legislative and executive branches, it has influenced our political, social, economic, and cultural lives.

When it comes to the history of racial justice, and injustice, in our State, we look primarily to its antecedents, and for this we turn to the origins of slavery in New York, its evolution, and eventual abolition. The soil of what we now call New York had supported cultures eons before Europeans arrived here in the early 17th century. There are other important facets of racial justice in our history, but in this twelvemonth, we look at the roughly four centuries of our most recent history dealing with slavery. As I am completing a book on the Lemmon Slave Case, I can oblige by extrapolating some of my research and findings into a broader picture.

At the start, we might make an especially telling observation: New York has had slavery longer than not. Its trajectory has been toward freedom, but the line was neither swift nor straight. There were many fits and starts along the way.

Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt

Images:

Map depicting the status of slavery in the United States from 1775-1865, published 1893. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library

Arrival of mail in New Amsterdam by Karl R. Free, a mural at the Ariel Rios Federal Building in Washington, D.C. Note the depiction of the enslaved person, in tattered clothing without shoes, receiving instruction about the mail delivery. Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The Court of Appeals originally sat in the Old Capitol Building in Albany. This photograph would have been taken around the time of the Lemmon Slave Case decision in the 1860s. Courtesy of New York State Archives, NYSA_A3045-78_X_8002

February 2021

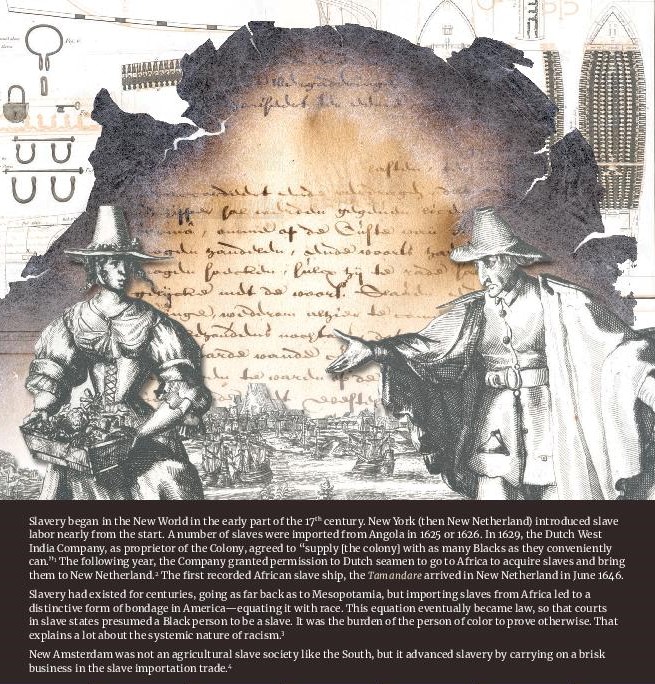

Slavery began in the New World in the early part of the 17th century. New York (then New Netherland) introduced slave labor nearly from the start. A number of slaves were imported from Angola in 1625 or 1626. In 1629, the Dutch West India Company, as proprietor of the Colony, agreed to “supply [the colony] with as many Blacks as they conveniently can.”[1] The following year, the Company granted permission to Dutch seamen to go to Africa to acquire slaves and bring them to New Netherland.[2] The first recorded African slave ship, the Tamandare arrived in New Netherland in June 1646.

Slavery had existed for centuries, going as far back as to Mesopotamia, but importing slaves from Africa led to a distinctive form of bondage in America––equating it with race. This equation eventually became law, so that courts in slave states presumed a Black person to be a slave. It was the burden of the person of color to prove otherwise. That explains a lot about the systemic nature of racism.[3]

New Amsterdam was not an agricultural slave society like the South, but it advanced slavery by carrying on a brisk business in the slave importation trade.[4]

[1] E.B. O’Callaghan, ed., Laws and Ordinances of New Netherland, 1638-1674 (1868), 10.

[2] Jaap Jacobs, New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America (2005), 380.

[3] For example, Hudgins v. Wrights, 11 Va. 134 (1806); Gibbons v. Morse, 7 N.J.L. 253 (1821); Boice v. Gibbons, 8 N.J.L. 324 (1826). This was true even of New Jersey when it was a slave state.

[4] Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (2004), 15; Graham Russell Gao Hodges, Root and Branch: African Americans in New York and East Jersey, 1613-1863 (1999), 29. See, generally, “Slavery in New Netherland,” New Netherland Institute, https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/history-and-heritage/digital-exhibitions/slavery-exhibit/slave-trade/.

Images:

Engraving depicting forms of industry in New Amsterdam, including tobacco planting. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library

Form of a contract for importing enslaved people from Africa, c. 1650. Courtesy of New York State Archives, NYSA_A1810-78_V11_45b

Depiction of the brig Vigilante, a vessel that transported 345 enslaved people from Africa to Europe in cramped quarters. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-07051

March 2021

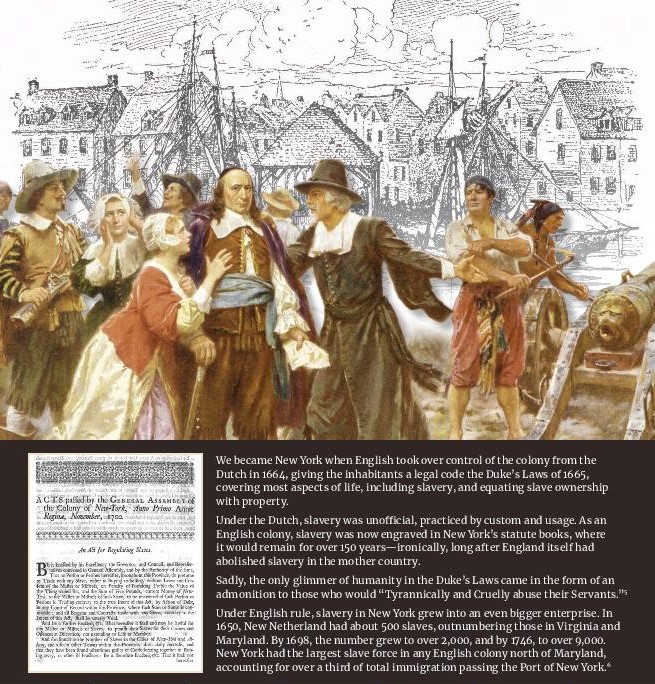

We became New York when English took over control of the colony from the Dutch in 1664, giving the inhabitants a legal code the Duke’s Laws of 1665, covering most aspects of life, including slavery, and equating slave ownership with property.

Under the Dutch, slavery was unofficial, practiced by custom and usage. As an English colony, slavery was now engraved in New York’s statute books, where it would remain for over 150 years—ironically, long after England itself had abolished slavery in the mother country.

Sadly, the only glimmer of humanity in the Duke’s Laws came in the form of an admonition to those who would “Tyrannically and Cruelly abuse their Servants.”[1]

Under English rule, slavery in New York grew into an even bigger enterprise. In 1650, New Netherland had about 500 slaves, outnumbering those in Virginia and Maryland. By 1698, the number grew to over 2,000, and by 1746, to over 9,000. New York had the largest slave force in any English colony north of Maryland, accounting for over a third of total immigration passing the Port of New York.[2]

[1] A renowned historian remarked: “That New York was not a slave state like Carolina is due to climate, and not the superior humanity of its founders.” George Bancroft, History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, Vol. I (1883), 513. In New York, slaves were not sought for work in factories, in contrast to Southern agricultural growth. Leo H. Hirsch, Jr., The Slave in New York, 16 Journal of Negro History 4 (October 1931): 384.

For a compilation of slavery laws in colonial New York, see John C. Hurd, The Law of Freedom and Bondage in the United States, Vol. I (1858), 277.

[2] See, Edgar J. McManus, A History of Negro Slavery in New York (1966), 25.

According to one commentator nearly 40% of all households in New York City owned slaves in 1698, the year of the first provincial census. Graham Russell Gao Hodges, Root and Branch: African Americans in New York and East Jersey, 1613-1863 (2003), 41.

Images:

An Act for Regulating Slaves, passed by the General Assembly of the Colony of New York, 1702. Courtesy of Hathi Trust/University of Michigan

Photoengraving of New York City’s slave market in 1730, published in 1902. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

Print depicting residents of New Amsterdam pleading with Peter Stuyvesant to surrender New Amsterdam to the British, who are waiting in the harbor to claim the territory for England, published c. 1932. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-12217

April 2021

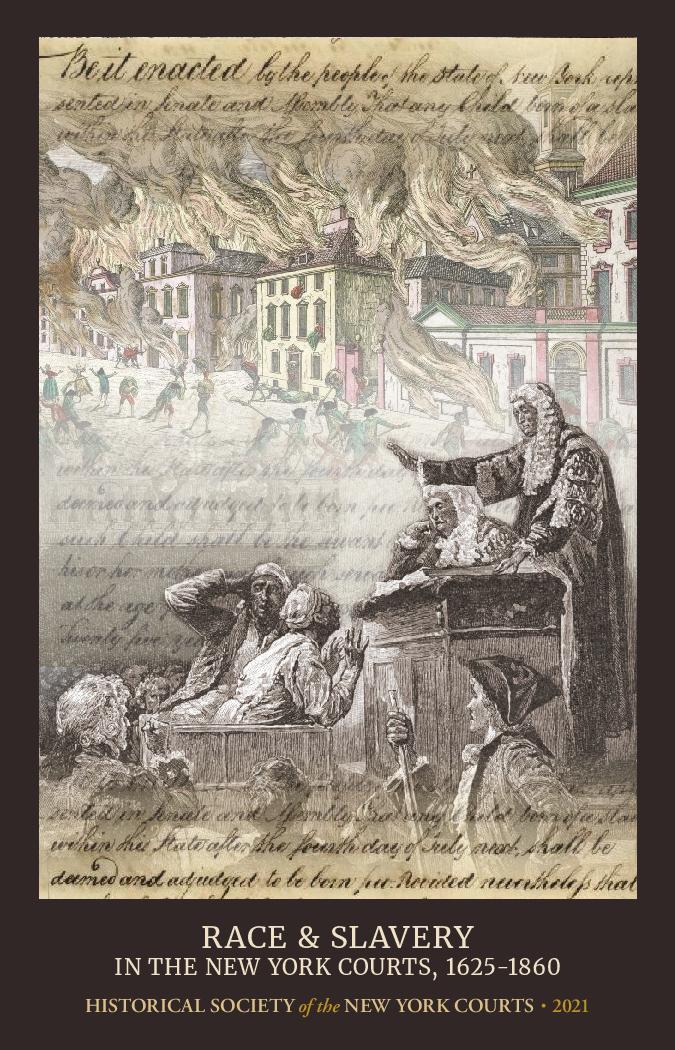

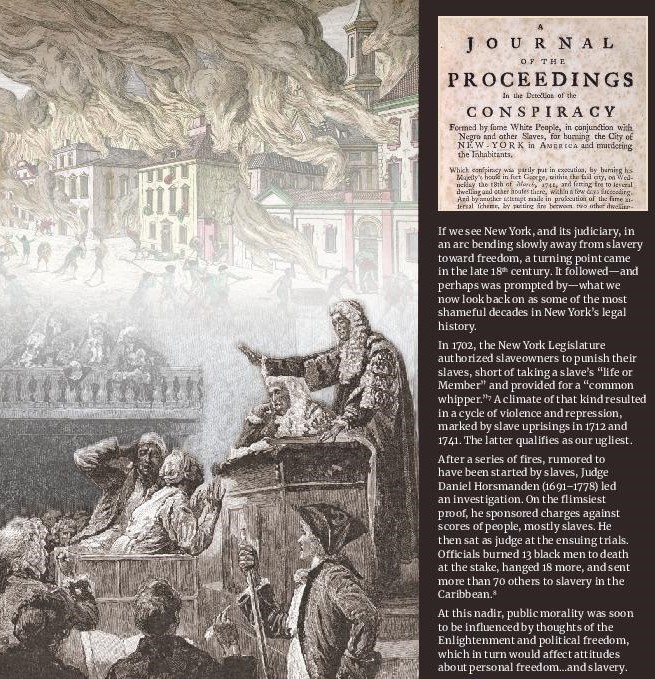

If we see New York, and its judiciary, in an arc bending slowly away from slavery toward freedom, a turning point came in the late 18th century. It followed—and perhaps was prompted by—what we now look back on as some of the most shameful decades in New York’s legal history.

In 1702, the New York Legislature authorized slaveowners to punish their slaves, short of taking a slave’s “life or Member” and provided for a “common whipper.”[1] A climate of that kind resulted in a cycle of violence and repression, marked by slave uprisings in 1712 and 1741. The latter qualifies as our ugliest.

After a series of fires, rumored to have been started by slaves, Judge Daniel Horsmanden (1691–1778) led an investigation. On the flimsiest proof, he sponsored charges against scores of people, mostly slaves. He then sat as judge at the ensuing trials. Officials burned 13 black men to death at the stake, hanged 18 more, and sent more than 70 others to slavery in the Caribbean.[2]

At this nadir, public morality was soon to be influenced by thoughts of the Enlightenment and political freedom, which in turn would affect attitudes about personal freedom…and slavery.

[1] L. 1702, ch. 123.

[2] The full 392-page Horsmanden report is available at https://www.loc.gov/resource/gcmisc.lst0063/?st=gallery.

Images:

Title page of Hon. Daniel Horsmanden’s report on the 1741 Slave Conspiracy Trials. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library

Engraving of Hon. Daniel Horsmanden’s courtroom as he sentenced enslaved people in the aftermath of the 1741 Slave Conspiracy Trials, published in 1881. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

Engraving depicting the New York Slave Conspiracy of 1741, published in 1776. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection

May 2021

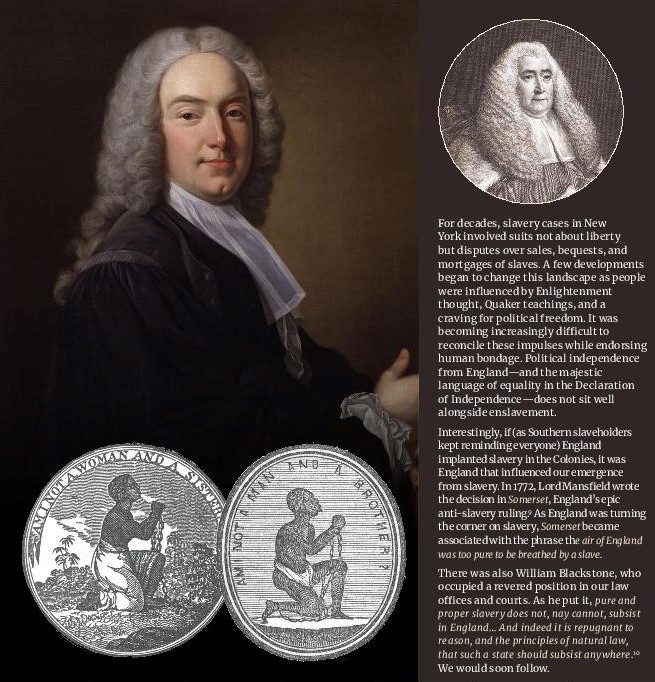

For decades, slavery cases in New York involved suits not about liberty but disputes over sales, bequests, and mortgages of slaves. A few developments began to change this landscape as people were influenced by Enlightenment thought, Quaker teachings, and a craving for political freedom. It was becoming increasingly difficult to reconcile these impulses while endorsing human bondage. Political independence from England—and the majestic language of equality in the Declaration of Independence—does not sit well alongside enslavement.

Interestingly, if (as Southern slaveholders kept reminding everyone) England implanted slavery in the Colonies, it was England that influenced our emergence from slavery. In 1772, Lord Mansfield wrote the decision in Somerset, England’s epic anti-slavery ruling.[1] As England was turning the corner on slavery, Somerset became associated with the phrase the air of England was too pure to be breathed by a slave.

There was also Blackstone, who occupied a revered position in our law offices and courts. As he put it, pure and proper slavery does not, nay cannot, subsist in England… And indeed it is repugnant to reason, and the principles of natural law, that such a state should subsist anywhere.[2] We would soon follow.

[1] R. v. Knowles, ex parte Somerset (1772) Lofft 1, 98 E.R. 499, 20 S.T. 1. Somerset v. Stewart, 1 Lofft 1, 1, 98 E.R. 499, 499 (K.B. 1772). Lord Mansfield (1705–1793) was William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, PC, SL, Chief Justice of the Court of King’s Bench, and one of England’s most eminent jurists.

[2] William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765), 1:423. This edition was the first of four volumes designed to provide a complete overview of English law. The treatise was repeatedly republished in 1770, 1773, 1774, 1775, 1778, and is still considered the magnum opus of English law.

Images:

William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield by Jean Baptiste van Loo, oil on canvas, circa 1737. NPG 474. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Engravings of an enslaved man and woman in shackles asking Am I not a man and a brother? and Am I not a woman and a sister? Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library

William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, 1775. Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School

June 2021

By the 1780s, New York was not ready to abolish slavery but took a significant stride along the way when its influential citizens formed the New York Manumission Society. Its founders included Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and Melancton Smith. They appreciated that most slaveowners in New York were not quite ready to renounce the institution (many members of the Manumission Society were themselves slaveholders), but knew it was on the horizon. To make the transition, it was necessary, they felt, to first educate the enslaved and then to release (manumit) them so they could become productive and respected citizens.

They formed the Society in 1785 with these words:

The benevolent Creator and Father of all men having given to them all an equal right to life, liberty, and property, no sovereign power on earth can justly deprive them of either, but in conformity to impartial government, and laws, to which they have expressly or tacitly consented.[1]

Even so, slavery existed, and the newspapers in New York commonly carried advertisements concerning slaves.

To further the education of enslaved people, the Society founded the New-York African Free-School in 1787 at 245 William Street and another on Mulberry Street in 1820. Notable alumni include Dr. James McCune Smith, the first Black doctor in the U.S., and Charles L. Reason, who later became a teacher at the Free-School.[2]

[1] Quoted in William Jay, Inquiry into the Character and Tendency of the American Colonization and American Anti-slavery Societies (1840), 112.

[2] Other notable alumni include Ira Aldridge, Alexander Crummell, George T. Downing, Henry Highland Garnet, Patrick H. Reason, and Samuel Ringgold Ward.

Images:

Engraving of New-York African Free-School, No. 2, published in 1830. The school was established by the New York Manumission Society and devoted to the education of Black children as preparation for a life as free citizens. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library

A formerly enslaved, and now free, woman escorting her children to school, 1862. The New-York African Free-School played a significant role in producing new leadership from within the New York Black community. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library

The Act of Incorporation and Constitution of the New York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, 1809. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library

July 2021

It is worth remembering that when our country was formed in 1788, every subscribing state abided slavery within its borders, including New York. Abolition began not long after, state by state.[1]

When New York ratified the Constitution, some of its political leaders balked at the slavery provisions, such as the three-fifths “compromise,” which gave Southern states slave-power by counting each slave as three-fifths of a person for purposes of national representation. In the Antifederalist Papers, Melancton Smith’s concerns were prescient:

What adds to the evil is, that these States are to be permitted to continue the inhuman traffic of importing slaves until the year 1808 — and for every cargo of these unhappy people which unfeeling, unprincipled, barbarous and avaricious wretches may tear from their country, friends and tender connections, and bring into those States, they are to be rewarded by having an increase of members in the General Assembly.[2]

At New York’s Ratification Convention, Smith went on to say what others would years later:

It will, however, by no means be admitted that the slaves are considered altogether as property. They are men, though degraded to the condition of slavery.[3]

[1] Only Vermont, which became a state in 1791, had a (partial) abolition provision in its own founding document.

[2] John Kaminski, et al., eds., The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Volume XIX: Ratification of the Constitution by the States: New York (2005), 253; John Kaminski, A Necessary Evil?: Slavery and the Debate Over the Constitution (1995), 127.

[3] “The Debates in the Convention of the State of New York on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution: In Convention, Poughkeepsie, June 17, 1788”, Constitution Society, available at https://www.constitution.org/rc/rat_ny.htm; Julius Goebel, Jr., “Melancton Smith’s Minutes of Debates on the New Constitution,” 64 Colum. L. Rev. 1 (January 1964).

Images:

Portrait of Melancton Smith, undated. Smith was a staunch supporter of abolition, and a founder of the New York Manumission Society. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library

Print of a parade in honor of the adoption of the federal constitution in 1788. Alexander Hamilton, whose name adorns the float, supported the adoption of the federal constitution and authored many of The Federalist Papers. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library

Alexander Hamilton’s notes on a speech by Melancton Smith during the New York Ratifying Convention, 1788. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Alexander Hamilton Papers

August 2021

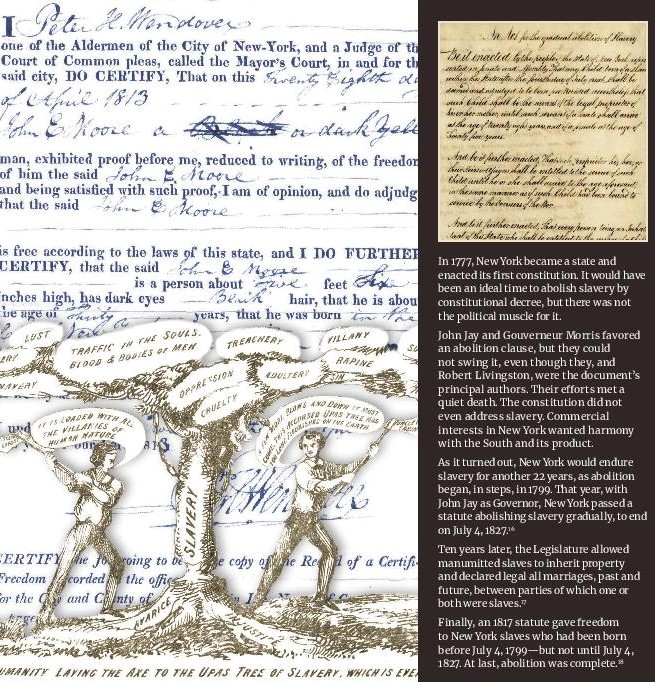

In 1777, New York became a state and enacted its first constitution. It would have been an ideal time to abolish slavery by constitutional decree, but there was not the political muscle for it.

John Jay and Gouverneur Morris favored an abolition clause, but they could not swing it, even though they, and Robert Livingston, were the document’s principal authors. Their efforts met a quiet death. The constitution did not even address slavery. Commercial interests in New York wanted harmony with the South and its product.

As it turned out, New York would endure slavery for another 22 years, as abolition began, in steps, in 1799. That year, with John Jay as Governor, New York passed a statute abolishing slavery gradually, to end on July 4, 1827.[1]

Ten years later, the Legislature allowed manumitted slaves to inherit property and declared legal all marriages, past and future, between parties of which one or both were slaves.[2]

Finally, an 1817 statute gave freedom to New York slaves who had been born before July 4, 1799 — but not until July 4, 1827. At last, abolition was complete.[3]

[1] L. 1799, ch. 62.

[2] L. 1809, ch. 44. Reportedly, 10,000 slaves were freed on July 4, 1827, without compensation to their former owners. Alice Dana Adams, The Neglected Period of Anti-Slavery in America (1808-1831) (1908), 90.

[3] L. 1817, ch. 137.

Images:

An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, 1799. Full abolition of slavery would come in 1827. New York State Archives, NYSA_13036-78_L1799_Ch062

Engraving captioned The friends of humanity laying the axe to the upas tree of slavery, which is ever loaded with the sum of all villanies, 1853. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library

Certificate from the City and County of New York for the manumission of John Moore, 1813. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library

September 2021

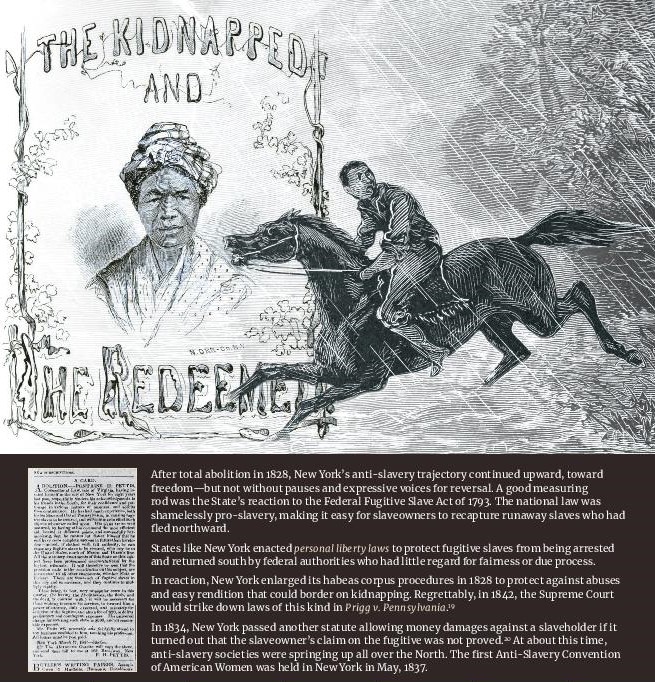

After total abolition in 1828, New York’s anti-slavery trajectory continued upward, toward freedom—but not without pauses and expressive voices for reversal. A good measuring rod was the State’s reaction to the Federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. The national law was shamelessly pro-slavery, making it easy for slaveowners to recapture runaway slaves who had fled northward.

States like New York enacted personal liberty laws to protect fugitive slaves from being arrested and returned south by federal authorities who had little regard for fairness or due process.

In reaction, New York enlarged its habeas corpus procedures in 1828 to protect against abuses and easy rendition that could border on kidnapping. Regrettably, in 1842, the Supreme Court would strike down laws of this kind in Prigg v. Pennsylvania.[1]

In 1834, New York passed another statute allowing money damages against a slaveholder if it turned out that the slaveowner’s claim on the fugitive was not proved. [2] At about this time, anti-slavery societies were springing up all over the North. The first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women was held in New York in May, 1837.

[1] For the 1828 legislation, see Rev. Stat. Part III, ch. 9, Tit. 1, art 1, p. 652; Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 41 US 539 (1842).

[2] L. 1834, ch. 88.

Images:

From The Kidnapped and the Ransomed: Being the Personal Recollections of Peter Still and His Wife “Vina” After Forty Years of Slavery by Mrs. Kate E.R. Pickard, 1856. Courtesy of Hathi Trust/Library of Congress

A New York attorney advertises his skills in helping slaveowners capture fugitive slaves in The Madisonian, 1841. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers

Engraving of a formerly enslaved person crossing a river on horseback during a rainy night as he travels on the Underground Railroad, published 1872. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library

October 2021

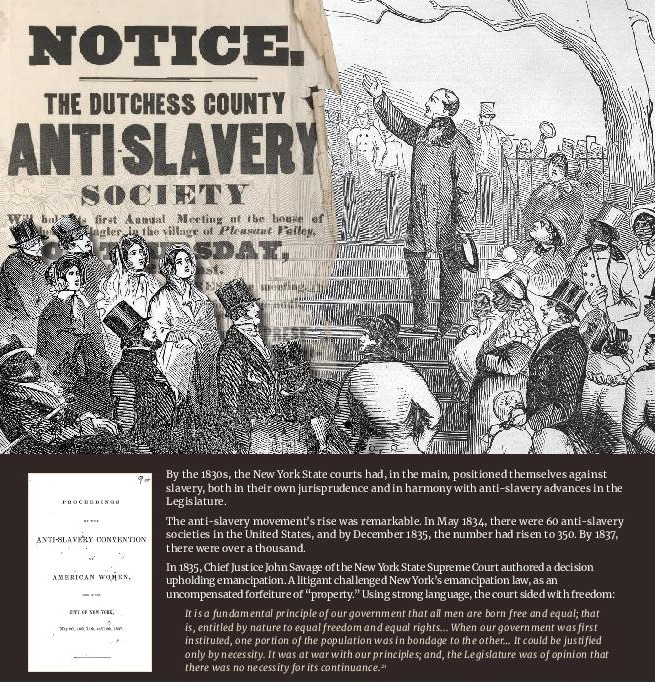

By the 1830s, the New York State courts had, in the main, positioned themselves against slavery, both in their own jurisprudence and in harmony with anti-slavery advances in the Legislature.

The anti-slavery movement’s rise was remarkable. In May 1834, there were 60 anti-slavery societies in the United States, and by December 1835, the number had risen to 350. By 1837, there were over a thousand.

In 1835, Chief Justice John Savage of the New York State Supreme Court authored a decision upholding emancipation. A litigant challenged New York’s emancipation law, as an uncompensated forfeiture of “property.” Using strong language, the court sided with freedom:

It is a fundamental principle of our government that all men are born free and equal; that is, entitled by nature to equal freedom and equal rights… When our government was first instituted, one portion of the population was in bondage to the other… It could be justified only by necessity. It was at war with our principles; and, the Legislature was of opinion that there was no necessity for its continuance.[1]

[1] Griffin v. Potter, 14 Wend. 209 (1835).

Images:

Title page of Proceedings of the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women: held in the city of New-York, 1837. Courtesy of the Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection, Cornell University Library

Notice of a meeting of the Dutchess County Anti-Slavery Society, 1839. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library

Engraving captioned Anti-slavery meeting on the Common, 1851. In the decades before the Civil War, the popularity and number of anti-slavery societies grew in the country. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

November 2021

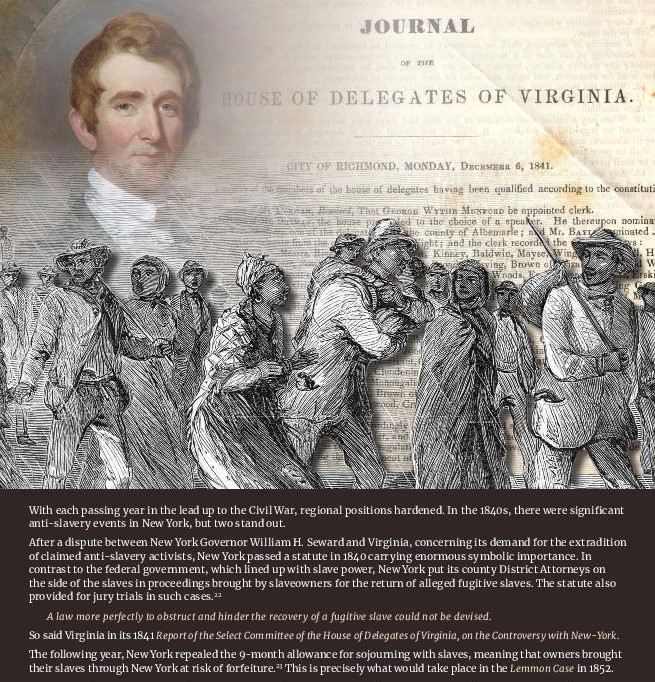

With each passing year in the lead up to the Civil War, regional positions hardened. In the 1840s, there were significant anti-slavery events in New York, but two stand out.

After a dispute between New York Governor William H. Seward and Virginia, concerning its demand for the extradition of claimed anti-slavery activists, New York passed a statute in 1840 carrying enormous symbolic importance. In contrast to the federal government, which lined up with slave power. New York put its county District Attorneys on the side of the slaves in proceedings brought by slaveowners for the return of alleged fugitive slaves. The statute also provided for jury trials in such cases.[1]

A law more perfectly to obstruct and hinder the recovery of a fugitive slave could not be devised.

So said Virginia in its 1841 Report of the Select Committee of the House of Delegates of Virginia, on the Controversy with New-York.

The following year, New York repealed the 9-month allowance for sojourning with slaves, meaning that owners brought their slaves through New York at risk of forfeiture.[2] This is precisely what would take place in the Lemmon Case in 1852.

[1] L. 1840, ch. 225

[2] L. 1841, ch. 247

Images:

Portrait of William H. Seward (1801-1872), former Governor of New York, by Henry Inman, 1844. Wikimedia Commons/Seward House Museum

From Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia, 1841. Around this time, Virginia’s Delegates disputed a New York statute that provided for county District Attorneys to defend formerly enslaved people in proceedings brought forth for the return of alleged fugitive slaves. Hathi Trust/University of Chicago

Engraving captioned Twenty-eight fugitives escaping from the Eastern Shore of Maryland, published 1872. Enslaved people travelled the Underground Railroad to head north where laws, like those in New York, typically afforded more protections. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library

December 2021

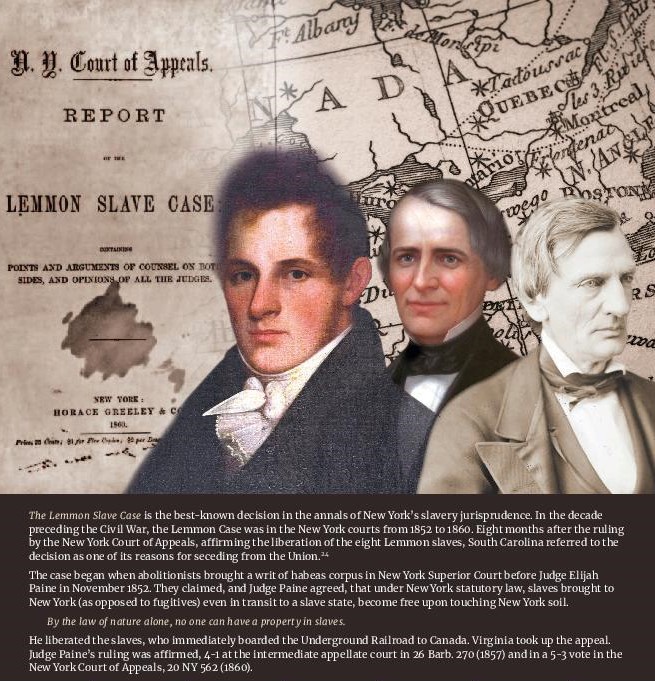

The Lemmon Slave Case is the best-known decision in the annals of New York’s slavery jurisprudence. In the decade preceding the Civil War, the Lemmon Case was in the New York courts from 1852 to 1860. Eight months after the ruling by the New York Court of Appeals, affirming the liberation of the eight Lemmon slaves, South Carolina referred to the decision as one of its reasons for seceding from the Union.[1]

The case began when abolitionists brought a writ of habeas corpus in New York Superior Court before Judge Elijah Paine in November 1852. They claimed, and Judge Paine agreed, that under New York statutory law, slaves brought to New York (as opposed to fugitives) even in transit to a slave state, become free upon touching New York soil.

By the law of nature alone, no one can have a property in slaves.

He liberated the slaves, who immediately boarded the Underground Railroad to Canada. Virginia took up the appeal. Judge Paine’s ruling was affirmed, 4-1 at the intermediate appellate court in 26 Barb. 270 (1857) and in a 5-3 vote in the New York Court of Appeals, 20 NY 562 (1860).

[1] South Carolina did not cite the case by name, but was obviously referring to Lemmon’s April 13, 1860 holding by the New York Court of Appeals: “In the State of New York even the right of transit for a slave has been denied by her tribunals.” (South Carolina Declaration of Secession, adopted December 24, 1860). Culver and Evarts were not alone in representing the eight slaves. John Jay II (1817-1894) was a crucial advocate on their behalf. Chester Arthur (1829-1886) while in his 20s in Culver’s office worked on the case at the intermediate appellate level. Judge Paine’s decision is in 5 Sandford 681 (N.Y. Superior Court, 1852).

Images:

Portrait of William M. Evarts (1818-1901), c. 1870. Evarts represented the Lemmon slaves on appeal, and later became Secretary of State to President Abraham Lincoln. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-cwpbh-05065

Portrait of Hon. Elijah Paine, Jr. (1796-1853), undated. Judge Paine decided the Lemmon Slave Case in the Superior Court, ruling that the enslaved people became free upon landing in New York. Photographed by Mark Hemhauser, 2017 and courtesy of Margaret Paine Hasselman, Albany, CA.

Portrait of Erastus D. Culver (1803-1889), undated. Culver represented the Lemmon slaves. Courtesy of the owner Henry D. Ryder, great-great grandson.

Cover of New York Court of Appeals Report of the Lemmon Slave Case, 1860. The case made for a watershed decision in going against the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dred Scott. Collection of the New York Court of Appeals