Description

New York’s First Constitution: From Implicit to Explicit Rights 1777-1821

For its time, and perhaps all the more so in retrospect, this document is a model of political theory and compromise. Setting an example for the federal constitution a decade later it contains a workable balance between executive and bicameral legislative powers. It makes provision for trial by jury, due process, and religious freedom, and places no restriction on suffrage based on race. It does not, however contain a bill of rights. That came later, in the second constitution (1821).

Judicial review

The Constitution made no mention of judicial review, a doctrine that became explicit with Marbury v. Madison1 in 1803. The concept was, nevertheless, implicit under common law as a judicial remedy. One writer points out that the well-known New York case of Rutgers v. Waddingto (1784) is an early, pre-Marbury example.2

Judicially applied rights

Although the Constitution of 1777 contained no bill of rights, courts relied on common law precepts to explicate them. For example, in Gardner v. Trustees of the Village of Newburgh3, the Chancellor held that the Legislature could not take away private property for public purposes without fair compensation

Similarly, in Thorn v. Blanchard4, in the absence of a constitutionally mandated free speech right, the Court ruled that in a petition to remove a public official for alleged malfeasance, there could be no liability for libel without a showing of malice.5

Endnotes:

1. 5 U.S. 137

2. Treanor, William Michael. “Judicial Review Before Marbury,” 58 Stan. L. Rev. 455 (2005)

3. 2 Johns. Ch. 162 (1816)

4. 5 Johns. 508 (1809)

5. As for the exercise of rights in the period from 1777 until the Bill of Rights in the 1821 Constitution, see Emery, R. “New York’s Statutory Bill of Rights: A Constitutional Coelacanth” Touro L. Rev. 363 (2003)

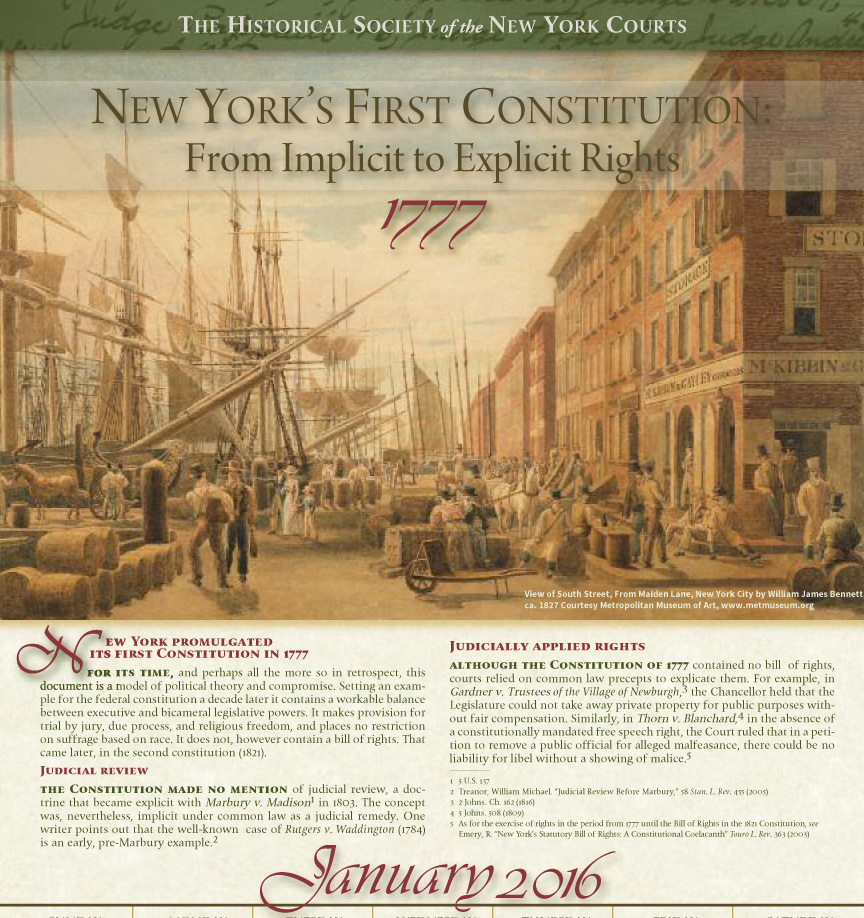

Image Caption:

View of South Street, From Maiden Lane, New York City

by William James Bennett, ca. 1827.

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org

February 2016

Our First Constitutional Bill of Rights

In 1787, the Legislature passed a statutory bill of rights that contained a “due process of law” clause, and other rights resembling what we recognize today as the State and Federal Bill of Rights, but it was not until the Constitution of 1821 that New York adopted its first formal Constitutional Bill of Rights. It was called the “Rights of citizens” and decreed at its opening the language of Magna Carta:

No member of this state shall be disfranchised or deprived of any of the rights or privileges secured to any citizen thereof, unless by the law of the land, or the judgment of his peers.

It also preserved the right to trial by jury; guaranteeing that:

the free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever be allowed in this state, to all mankind…

As a measure of separation of church and state, it provided that Clergymen were not eligible for any civil or military office

It also excused religious objectors from military service (upon payment of financial equivalency), and in language similar to the United States Constitutional Amendments of 1791 provided for habeas corpus, grand jury indictment, and against double jeopardy and self-incrimination.

In words echoing New York’s statute of 1787 it provided that no person “shall be…deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law;”

It provided compensation for public use takings, and in language more expansive than the federal constitution’s first amendment, guaranteed every citizen the right to “freely speak, write, and publish his sentiments on all subjects,” with truth as a defense against libel – recalling without mentioning the Zenger 1 (1735) and Croswell2 (1804) cases.

Endnotes:

1. L.1787, ch.1

2. 3 Johns. 336; see also, McGrath, Paul, “People v. Croswell,” Judicial Notice #7 (2011).

Image Captions:

Abraham Yates.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

Philip Schuyler.

Schenectady County Public Library

Lewis Morris

John Wollaston, c. 1750.

National Portrait Gallery

March 2016

The Separation of Powers

The concept of separation of powers is the basic structure for American Constitutionalism. The idea is credited to Montesquieu, and was elaborated upon by James Madison in Federalist 47. Here is what he said about our State constitution:

The constitution of New York contains no declaration on this subject; but appears very clearly to have been framed with an eye to the danger of improperly blending the different departments.

Although the lines of separation were not finely delineated at the outset, the concept was eloquently worded by New York’s Supreme Court of Judicature in Dash v. Van Kleeck.1

Our government, like all the other free governments upon this continent… contains a marked separation of the legislative and judicial powers. The constitutions of several of the United States… have an express provision that the legislative and judicial powers shall be preserved separate and distinct, so that one department shall not exercise the functions belonging to the other. …And if it be not found in our own constitution, in terms, it exists there in substance; in the organization and distribution of the powers of the departments, and in the declaration that the “supreme legislative power” shall be vested in the Senate and Assembly. No maxim has been more universally received and cherished as a vital principle of freedom. And without having recourse …to the popular conventions of Europe, we have a most commanding authority, in the sense of the American people, that the right to interpret laws does, and ought to belong exclusively to the courts of justice.

Endnote:

1. 7 Johns. 477 (1811), (Kent, J.)

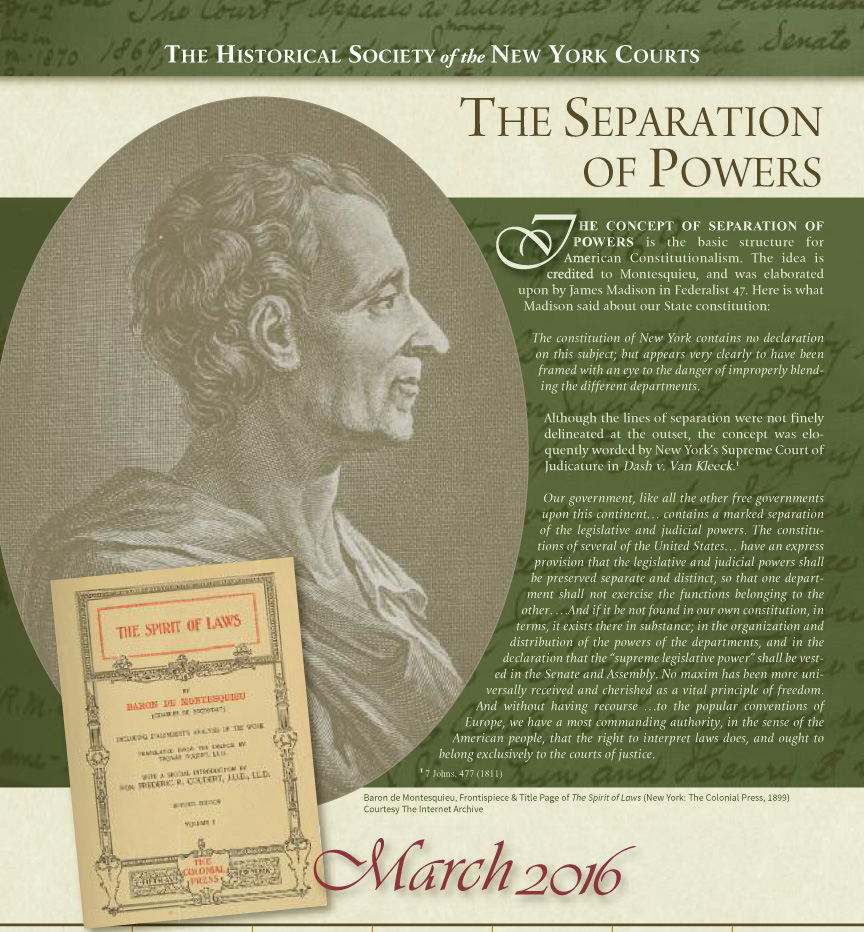

Image Captions:

Baron de Montesquieu, Frontispiece & Title Page of The Spirit of Laws (New York: The Colonial Press, 1899). Courtesy The Internet Archive.

April 2016

Dueling and Its Non-Lethal Punishments

Although the constitution of 1821 contained a Bill of Rights that in many ways mirrored the Constitution’s amendments of 1791, it contained no prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

The omission was dramatized in the prosecution of Jacob Barker, for dueling.1

The story begins with An Act to Suppress Dueling, by which the legislature, in 1816, prescribed that a person who challenges another to fight a duel becomes ineligible to hold civil or military office in New York.

Barker was born in Maine in 1779 and at 16 came to New York, where he amassed a fortune and founded the Exchange Bank of New York. In 1816 he was a New York State Senator. Suffering an insult, he challenged the party to a duel. Upon losing his office, Barker argued that the punishment of disenfranchisement violated the State Constitution.

Turning to the cruel and unusual argument he contended:

Another fundamental principle of all free governments is, that punishments shall be proportioned to the nature of the offense. This is…incorporated as a maxim in various Constitutions of the United States. Cruel or unusual punishments are not to be inflicted. And though not, in terms, a part of our State Constitution, it is one of its fundamental principles, as much as the rule that the freehold of one man shall not be arbitrarily divested and conferred upon another.

New York’s high court – then a mix of senators and judges, rejected Barker’s claim and asserted that the punishment was not the least bit unusual. It was one of the earliest interpretations of 8th amendment language – as the United States Supreme Court noted in 1991, citing the Barker case in Harmelin v. Mich.2

Two aftermaths:

• New York’s next Constitution (1846) included the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

• Governor Clinton removed all of Barker’s disabilities and restored him to full citizenship.3

Endnotes:

1. Barker v. People, (3 Cow. 686, 1824)

2. 501 U.S. 957

3. See Life of Jacob Barker (Washington, 1855), 147

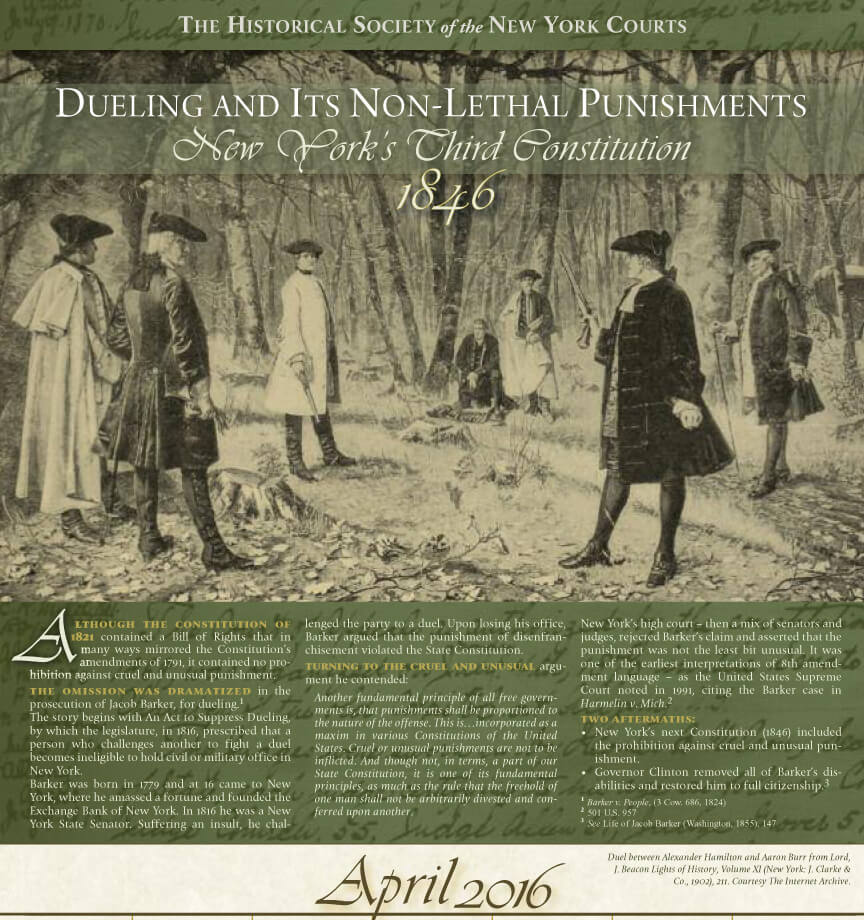

Image Caption:

Duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr from Lord, J. Beacon Lights of History, Volume XI (New York: J. Clarke & Co., 1902), 211. Courtesy The Internet Archive.

May 2016

Substantive Due Process makes its debut: The spirit(s) of the law

Due Process had also grown, and began to take on a substantive character. Notably, and perversely, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney initially employed the 5th Amendment’s due process clause in Dred Scott v. Sandford to strike down the Missouri Compromise as a violation of the slaveholder’s property rights.

In Buffalo, Wynehamer was convicted for selling liquor in violation of the 1855 “Act for the prevention of intemperance, pauperism and crime,” The Act compelled forfeiture and destruction of the liquor upon conviction. In a companion case Toynbee was arrested in Brooklyn for selling a glass of brandy and a bottle of champagne.

In seven separate opinions the court held that the Act violated State Constitutional due process, by forcing those who legally possessed the liquor before enactment of the law to destroy their property. In a ringing defense of due process, adverting to Magna Carta, the Court held:

In a word, that which belongs to the citizen in the sense of property, and as such has to him a commercial value, cannot be pronounced worthless or pernicious, and so destroyed or deprived of its essential attributes. Sir William Blackstone…said: “So great is the regard of the law for private property, that it will not authorize the least violation of it, no, not even for the general good of the whole community…”

With…exceptions…so minute and trivial as scarcely to disturb the general scheme, the act is one of fierce and intolerant proscription.

Endnote:

1. 13 NY 378 (1856)

Image Caption:

Detail from The Drunkard’s progress, or the direct road to poverty, wretchedness & ruin. Library of Congress, Print & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-32721

June 2016

Liberty: For the price of a cigar

If Wynehamerand Toynbee expanded substantive due process by way of a glass of brandy, it was Peter Jacobs, cigarmaker, who widened the definition of one’s “liberty” interest under the State Constitution’s Due Process clause.

In 1884, Jacobs was arrested for making cigars in his New York City tenement apartment. He lived there with his wife and two children, and shared the building with three other families. Jacobs was charged with violating “An act to improve the public health by prohibiting the manufacture of cigars…in tenement houses…”

The court struck down the statute as impairing Jacobs’s “liberty interest”:

What does this act attempt to do? In form, it makes it a crime for a cigarmaker [only] in New York and Brooklyn… to carry on a perfectly lawful trade in his own home. Whether he owns the tenement-house or has hired a room…[to] prosecuting his trade, he cannot manufacture therein his own…cigars for his own use or for sale, and…will become a criminal for doing [what] is perfectly lawful outside of the two cities named – everywhere else, so far as we are able to learn, in the whole world.

In the unceasing struggle for success and existence… he may be deprived of that which will enable him to maintain his hold and to survive. He may go to a tenement-house, and finding no one [there]… hire a room…to carry on his trade, and afterward someone may commence to sleep or to do some household work [in the tenement], even without his knowledge and he at once becomes a criminal…

It is, therefore, plain that this law…trammels him in the application of his industry and the disposition of his labor, and…arbitrarily deprives him of his property and of some portion of his personal liberty.1

At last count, this case has been cited in over 400 cases nationally and over 100 law review articles and treatises.

Endnote:

1. Matter of Jacobs (98 NY 98, 1885)

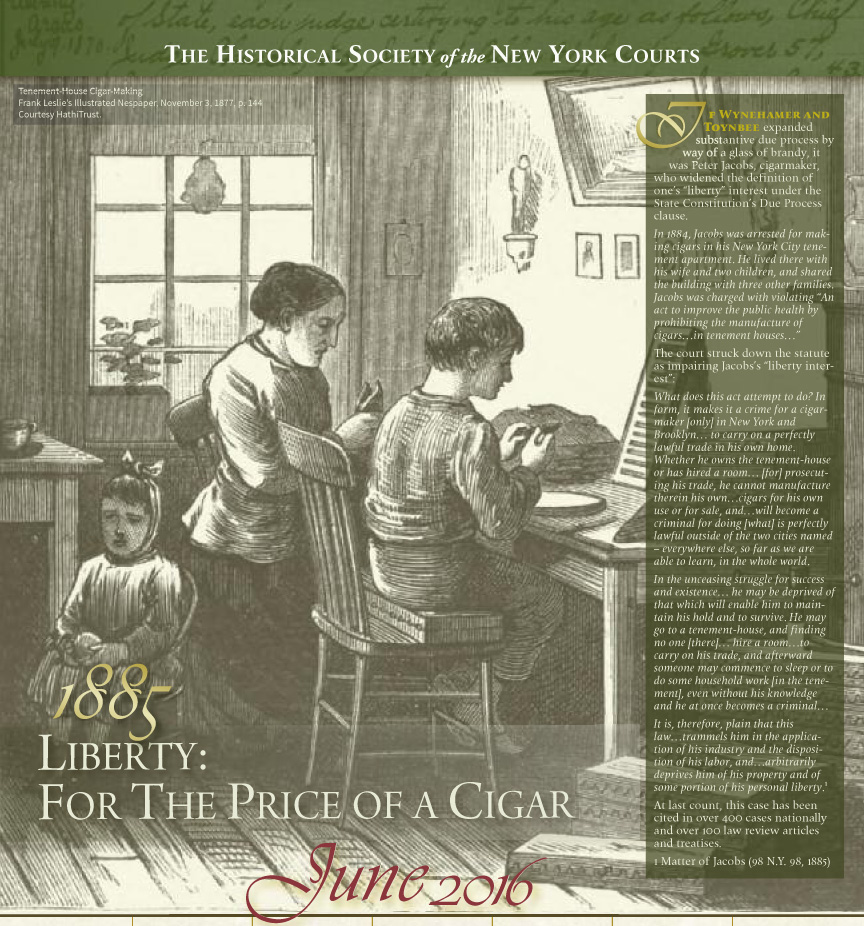

Image Caption:

Tenement-House Cigar-Making, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 3, 1877, p. 144. Courtesy HathiTrust.

July 2016

Freedom of Contract and the Lochner Era

The Lochner era refers to an epoch in which the United States Supreme Court, invoking the doctrine of substantive due process, struck down legislation limiting the daily and weekly hours of employment. Today it is seen as a time, during the early 1900s, that expanded the rights of corporations at the expense of worker protection.1 The imagery is of sweat shops and worker exploitation.

In 1899, Joseph Lochner, a bakery owner, was indicted by an Oneida Grand Jury for violating the Bakeshop Act, prohibiting employee to work more than 60 hours per week. Lochner drew a small fine from the Oneida County Court, and he appealed to the Appellate Division, Fourth Department. The conviction was upheld, and Lochner again appealed to the New York Court of Appeals.

The New York Court of Appeals upheld the conviction as against the employer’s claim that he was being denied his right to contract and his State Constitutional right to due process.2

The Court held:

That the public generally are interested in having bakers’ and confectioners’ establishments cleanly and wholesome in this day of appreciation of, and apprehension on account of, microbes, which cause disease and death, is beyond question. [Bakers are] relied on…to furnish bread, biscuits, cake and pie, as well as confectionery, while over many country roads the bakers’ wagons go twice a week or more to supply the farmers and inhabitants of small settlements with their wares. Indeed it can be safely said that the family of to-day is more dependent upon the baker for the necessaries of life than upon any other source of supply. That being so it is within the police power of the legislature to so regulate the conduct of that business as to best promote and protect the health of the people.

In the name of the right to contract and substantive due process, the United States reversed the Court of Appeals and struck down the statute.

The Supreme Court overruled Lochner in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish,3 this time affirming the New York Court of Appeals.4

Endnotes:

1. Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905)

2. People v. Lochner, 177 N.Y. 145 163 (1904)

3. 300 U.S. 379 (1937)

4. People v. Nebbia, 262 N.Y. 259 (1933)

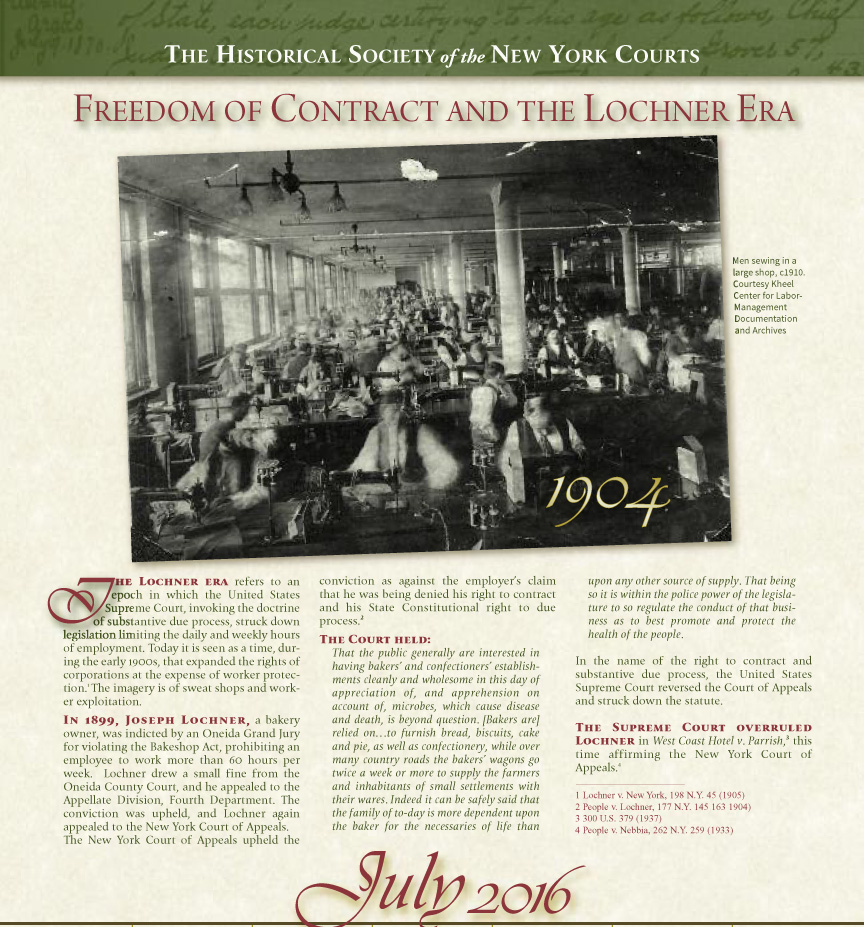

Image Caption: Men sewing in a large shop, c1910. Courtesy Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives

August 2016

Free to be you and me: Anti-drabness under the State Constitution

Due Process has multiple components: Though it speaks chiefly of life, liberty, and property, it also guarantees that a law shall not be unreasonable, arbitrary or capricious.

In a wry and cheeky decision, Judge Frederick Crane made this plain in People v. O’Gorman:1

Rose O’Gorman and William Matthias were going through Yonkers on June 21, 1936, when they were arrested because of the clothes they had on or did not have on. The girl had on “white sandals, no stockings, yellow short pants and a colored halter, with a yellow jacket over it and no hat;” the boy or young man “had on white sneakers, white anklets, short socks, yellow trunks, short pants, a blue polo shirt, brown and white belt, no hat.”…[The arresting] officer said to them, “Well, you haven’t got what we term ‘customary street attire,’ and haven’t a skirt on.”

In a writing that speaks for all of us hikers, bikers, and bathers, Judge Crane continued:

To meet the cases of persons who insist upon being conspicuous by exposing too much of their anatomy, it may be reasonable to prescribe that men and women shall cover themselves, at least when on the street. This ordinance in question, however…is so vague and meaningless as to reach many harmless and insipid foibles. Indecency as commonly understood may be prohibited but this ordinance goes too far. No man or woman is obliged to wear the “ordinary street attire…” Customary, not exceptional, street attire has rather a drab appearance; if some desire to color it up a bit, where is the harm? All kinds of uniforms and special apparel for purposes of pleasure or advertising or the like may disfigure or adorn the highway, but freedom in these matters may not be unreasonably restrained, even if foolish. The Constitution still leaves some opportunity for people to be foolish if they so desire. Sometimes a little folly saves us from more serious trouble. Be this as it may, the ordinance is too vague to be legal.

Endnote:

1. 274 N.Y. 284, 284-285 (1937)

Image Caption: Women Walking Down Coney Island Boardwalk. Reginald Marsh, ca. 1938, Courtesy Museum of the City of New York

September 2016

Equal Protection

Our State Constitution guarantees equal protection under the law. Over a century ago George Tyroler, a freelance steamship ticket seller, took his case to the New York Court of Appeals to prove it. He was arrested on September 16, 1897 for selling a $6.30 steamship ticket in violation of Penal Code Sec 616, which prohibited ticket sales by anyone not an “authorized agent” of the company. He argued that this charge was, among other things, a violation of his equal protection rights under the New York Constitution.

The Court agreed, in a sharply worded decision by Judge Alton Parker, who pointed out that if it lives, the statute could mark the end of Cook’s tours:

And Cook’s and Gaze’s are among the agencies that must go out of business in this state if this statute can live, unless some transportation company shall deem it wise to clothe them with the authority to act as its agents.

It is asserted by counsel that the traveling public and the transportation companies have been so defrauded [by ticket sellers], as to call for [protective legislation]. The tendency of the times undoubtedly is to rush to the legislature for a cure for all the grievances of citizens, whether real or imaginary, and many novel experiments in legislation are the result.1

Judge Parker also smelled a rat in this scheme:

Still another motive for this enactment is suggested, and that is ….to enable transportation companies to compel others with which they may enter into pooling arrangements to preserve their agreement from secret violation, which is frequently the outcome under the present ticket brokerage system, which offers an avenue by which the weaker corporation to such an agreement can dispose of its tickets at a price lower than that agreed upon.2

In 1904 Judge Parker, somewhat reluctantly, was drafted to run on the democratic line, against Theodore Roosevelt, for the office of President of the United States.

Endnotes:

1. People ex rel. Tyroler v. City Prison of N.Y., 157 NY 116 (1898)

2. 157 NY 116 (1898)

Image Caption: 1900 Philadelphia World’s Fair Steamship Tour Agent Card

October 2016

New York’s Constitutional Right to an Education

Provision for education made its initial appearance in the Constitution of 1821, when it required that all proceeds from the sale of state lands be committed to a perpetual fund for the support of the common schools of the state. A proposal for free schooling failed.

Success arrived in the Constitution of 1894, in which Article XI directed the legislature to provide for free common schools for all the children in the State – recognizing constitutionally what had been State policy for some time. It also prohibited the use of public property or money in aid of denominational schools.

Over the years, the Educational Article has generated litigation, and the Court of Appeals in Bd. of Educ. v. Nyquist1 interpreted the Article to require a “sound basic education.”

In Campaign for Fiscal Equity, Inc. v. State2 the Court of Appeals elaborated on the Nyquist case:

…mandating a school system “wherein all the children of this state may be educated,” the State has obligated itself constitutionally to ensure the availability of a “sound basic education” to all its children.(86 NY2d at 314.)

The Court went on to state:

We…indicated that a sound basic education conveys not merely skills, but skills fashioned to meet a practical goal: meaningful civic participation in contemporary society. This purposive orientation for schooling has been at the core of the Education Article since its enactment in 1894. As the Committee on Education reported at the time, the “public problems confronting the rising generation will demand accurate knowledge and the highest development of reasoning power more than ever before…” (2 Documents of 1894 NY Constitutional Convention No. 62, at 4).

Endnotes:

1. 57 N.Y.2d 27 (1982)

2. 100 N.Y.2d 893, 902 (2003)

Image Caption: School in Session. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-nclc-04354

November 2016

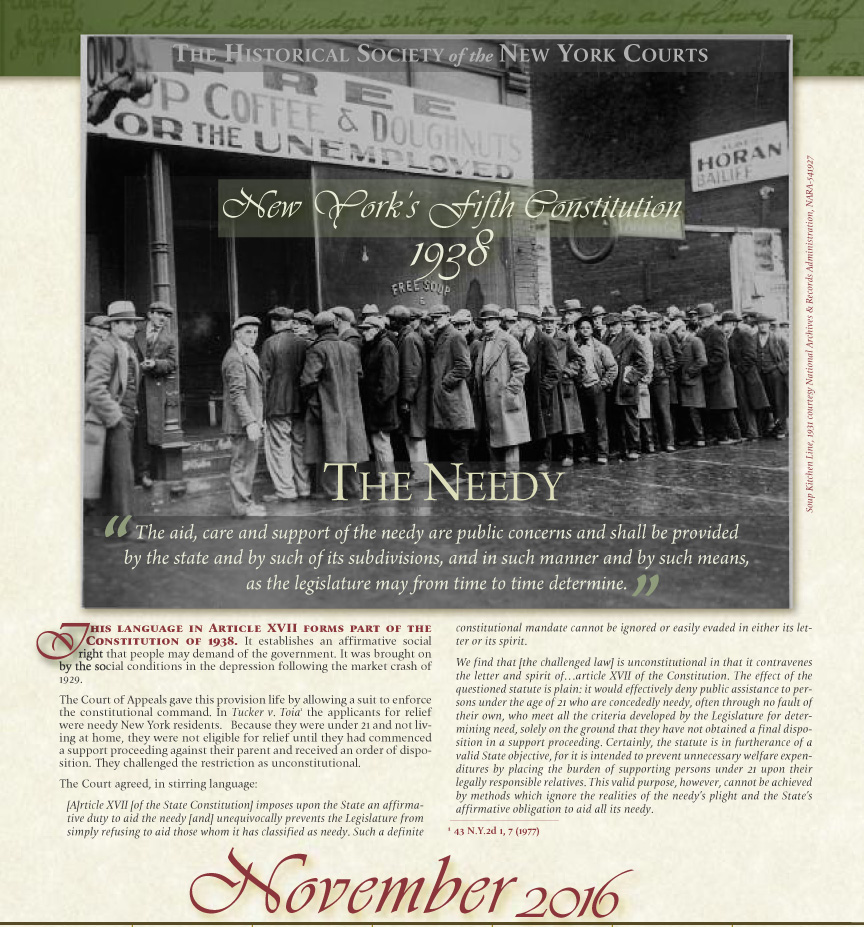

The Needy

The aid, care and support of the needy are public concerns and shall be provided by the state and by such of its subdivisions, and in such manner and by such means, as the legislature may from time to time determine.

This language in Article XVll forms part of the Constitution of 1938. It establishes an affirmative social right that people may demand of the government. It was brought on by the social conditions in the depression following the market crash of 1929.

The Court of Appeals gave this provision life by allowing a suit to enforce the constitutional command. In Tucker v. Toia1 the applicants for relief were needy New York residents. Because they were under 21 and not living at home, they were not eligible for relief until they had commenced a support proceeding against their parent and received an order of disposition. They challenged the restriction as unconstitutional.

The Court agreed, in stirring language:

[A]rticle XVII [of the State Constitution] imposes upon the State an affirmative duty to aid the needy [and] unequivocally prevents the Legislature from simply refusing to aid those whom it has classified as needy. Such a definite constitutional mandate cannot be ignored or easily evaded in either its letter or its spirit.

We find that [the challenged law] is unconstitutional in that it contravenes the letter and spirit of…article XVII of the Constitution. The effect of the questioned statute is plain: it would effectively deny public assistance to persons under the age of 21 who are concededly needy, often through no fault of their own, who meet all the criteria developed by the Legislature for determining need, solely on the ground that they have not obtained a final disposition in a support proceeding. Certainly, the statute is in furtherance of a valid State objective, for it is intended to prevent unnecessary welfare expenditures by placing the burden of supporting persons under 21 upon their legally responsible relatives. This valid purpose, however, cannot be achieved by methods which ignore the realities of the needy’s plight and the State’s affirmative obligation to aid all its needy.

Endnote:

1. 43 N.Y.2d 1, 7 (1977)

Image Caption: Soup Kitchen Line, 1931. Courtesy National Archives & Records Administration, NARA-541927

December 2016

Forever Wild: New York Constitution Article XIV

In 1894, a Constitutional Convention approved a new Article VII (now XIV), bringing New York’s Forest Preserve lands under the state’s highest level of protection. This proposal, combined with other amendments from the Convention, was approved by the people at the 1894 General Election and became effective on January 1, 1895. Article XIV’s original wording, found below, still survives today in spite of numerous efforts to modify it.1

The Article was adopted without a single dissenting vote.

The provision reads:

The lands of the state, now owned or hereafter acquired, constituting the forest preserve as now fixed by law, shall be forever kept as wild forest lands. They shall not be leased, sold or exchanged, or be taken by any corporation, public or private, nor shall the timber thereon be sold, removed or destroyed.

The language is so uncompromising that for each desired use (such as scientific forestry and others) a Constitutional amendment is required –of which there have been at least 15. Fortunately for skiers, the specific language of the Article allows for some of that.

Happy New Year.

Endnote:

1. For general reference, see Galie, Peter. Ordered Liberty (1966). An excellent reference work on which I drew heavily for this and other months.

Image Caption: An Adirondack mountain stream. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LIC-DIG-ppmsca-18239