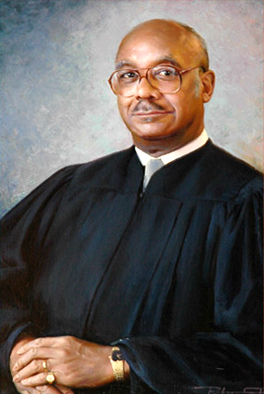

Born Carl Bernard Zanders, Jr., in Apopka, Florida, on April 24, 1926, Fritz Winfred Alexander, II was later given the name of his mother’s brother, a Gary, Indiana, lawyer with whom he went to live after his mother became ill.[1] Upon surveying the Judge’s long and illustrious legal career, it becomes apparent that the elder Alexander gifted to his young nephew not only his euphonious name, but also imparted a drive for excellence, an inclination toward public service and social justice, and a passion for the rule of law.

Judge Alexander’s appointment to the Court of Appeals on January 2, 1985 by Governor Mario Cuomo marked a significant milestone in the Court’s history: he was the first Black American to be appointed to a full fourteen-year term on the Court.[2] Upon his nomination, the fourteen-member Committee on Judicial Selection of the New York State Bar Association judged him to possess “pre-eminent qualifications” and concluded that he was “well-qualified” for the position of Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals. Although the Judge was keenly aware of historical and social import of his appointment, he was adamant that his paramount allegiance on the Court was to the people of New York and to the rule of law. At his confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee (which voted his nomination unanimously), he acknowledged the “symbolic significance” of his status as the first Black American to be elevated to a full term on the Court of Appeals,[3] and upon taking the bench insisted that he was appointed not because of his race, but because he was “a good judicial choice,” and that his paramount role was “to serve the people of this state as a judge of this court.”[4] On the occasion of his leaving the Court after only seven years into his term, and four years shy of the mandatory retirement age of 70, he remarked that he most wanted to be known “as a jurist who sought to discharge his responsibilities to the very best of his ability, to serve justice and the rule of law, and about whom it can be said ‘job well done.”[5]

While Alexander sought to downplay his race, even as a judge he was not immunized from racial prejudice and discrimination. In her memorial remarks after his death in 2000, Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye remembered that the Judge shared personal accounts of his experiences of invidious discrimination “not with bitterness but with clear resolve to effect change.”[6] It is not surprising, then, that when confronted by racism from the infamous Ku Klux Klan, Judge Alexander took the incident in stride. Sometime between Friday night, January 16, 1981 and the following Saturday morning, the suite of judges’ chambers on the 17th floor of the Criminal Courts Building at 100 Centre Street in Manhattan was burglarized.” According to the New York Times report, six chambers were invaded, nine typewriters stolen, and “the chambers of a black State Supreme Court justice ransacked and the letters ‘KKK’ scrawled on the walls . . . Only the chambers of Justice Fritz W. Alexander, who is black, were defaced.”[7] Characteristically, Judge Alexander didn’t want the incident “blown out of proportion.”[8]

By 1992, Alexander had established a reputation for his deliberative approach to jurisprudence, his strong commitment to individual rights, and for the “three-alarm” chili which he occasionally cooked up for other judges.[9] That year, just four years shy of the Court of Appeal’s mandatory retirement age, and seemingly at the pinnacle of his career, Alexander stunned many of his colleagues and friends when he voluntarily left the Court to join the administration of his New York University School of Law classmate and former law partner, David Norman Dinkins, the first African-American mayor of the City of New York.[10] In a move that “took the legal community by surprise,”[11] Alexander left behind what he described as “the relative tranquility of the Court”[12] for New York City’s chaotic criminal justice system to take on what one reporter described as “a relentlessly fractious criminal-justice system as a bureaucratic traffic cop, mayoral troubleshooter, and (on occasion) interagency mud-wrestling referee.”[13] According to New York Newsday, Alexander’s toughest task in his new job would be “forcing a bloated NYPD to shoo more cops out from behind desks and onto the streets.”[14] Not surprisingly, “many were critical of his choice. They saw it as folly, a step in the wrong direction.”[15] Even Dinkins himself said that he was surprised when Alexander accepted the thankless job of overseeing the city’s Police, Fire, Correction and Probation departments.[16]

While his decision to leave one of the nation’s most prestigious legal positions at the height of his career confounded many of his colleagues, the move was consistent with his well-established commitment to family and friendship, and his penchant for confronting important challenges. A year into the job, Alexander expressed no regrets about his decision, and explained that it was “home and friendship” and the challenge of the job, that led him to step down from the bench,[17] as well as a longing for something different after twenty-two years as a judge.[18] The opportunity to assist his longtime friend David Dinkins, to help his beloved New York City through its fiscal and civil woes, along with the chance to be closer to home and to his wife, Beverly, apparently was an irresistible combination.