This article was written by Robert Murphy, president of the Beacon Historical Society.

Photo: Descendants of Chancellor James Kent standing before his restored gravestone at a ceremony, presented by The Historical Society of the New York Courts and the Beacon Historical Society, which took place on October 30th, 2016 at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, Beacon, NY.

(L-R): Mary V. Turner Cattan (4th Generation); Harry Boers; Anne Turner (5th Generation); Kent Turner (4th Generation); Katharine Turner Berger (5th Generation); Elizabeth Berger (6th Generation); Deborah Smith (5th Generation); Ellen Turner; Jean Shea (5th Generation); Amy Turner (6th Generation); Ryan Miller

Attending the unveiling of the Kent Gravestone, along with the Kent family and representatives of the Beacon Historical Society, were the staff of The Historical Society of the New York Courts, Marilyn Marcus, Executive Director, Daniel O. Sierra, Marketing Director, and Allison Morey, Administrative Director; the President of the Society, Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt; and Society Trustees Hon. Helen Freedman and Frances Murray.

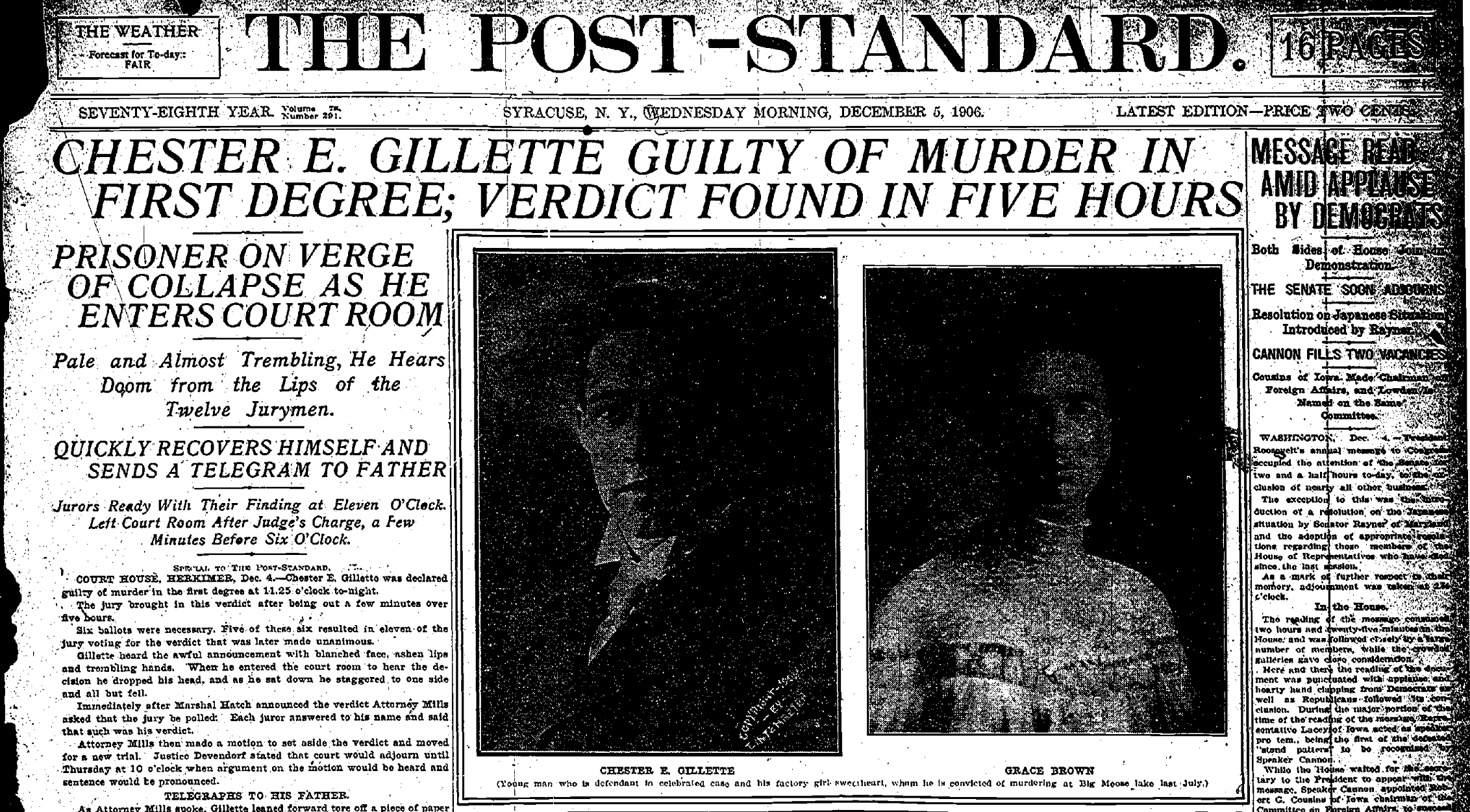

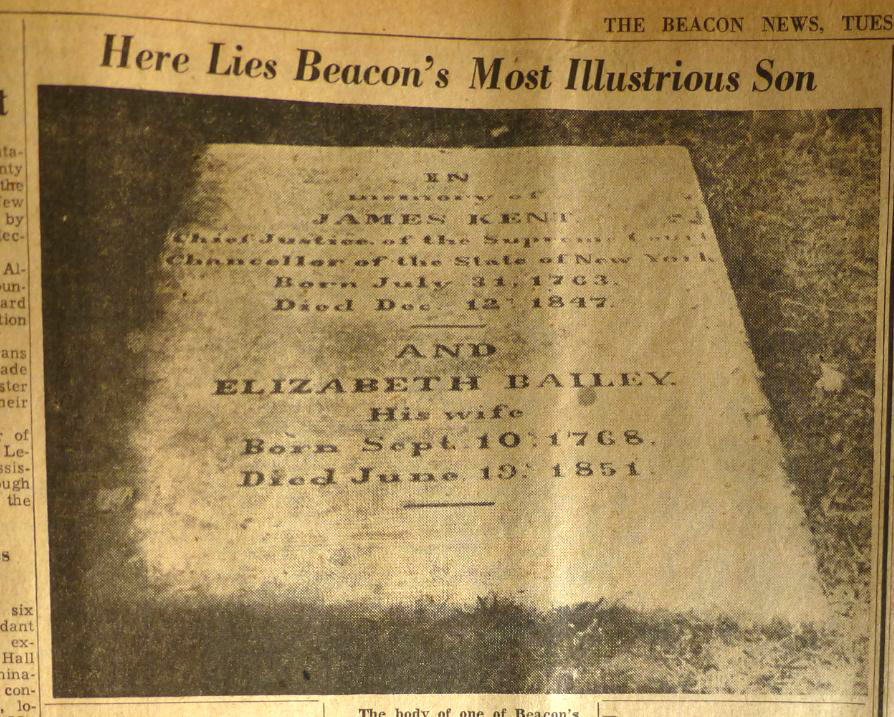

“Here Lies Beacon’s Most Illustrious Son” reads the headline over the photo of a gravestone in a 1939 edition of Beacon’s (New York) local newspaper. The headline was referring to James Kent, the eminent jurist and the former Chancellor of New York, and most famously, “the American Blackstone” — author of the seminal nineteenth-century law literary work, Commentaries on American Law. The newspaper lamented back in 1939 (about ninety years after his death) that Kent and his legacy had all but been forgotten by local townspeople, as evidenced by the toppling of his large, marble table top stone that even then was sinking into the sod.

Speed forward to 2013, and the headline might read: “James Kent — Buried, Forgotten and Missing”… for by that date his stone had disappeared, covered over by the grasses of St. Luke’s Church Cemetery. The year 2013 also happened to be the city of Beacon’s centennial, and the Beacon Historical Society’s cemetery committee, spurred on by the 1939 news photo of Kent’s stone, was determined this was the opportune time to find the missing grave of our city’s most Illustrious Son.

How did James Kent happen to be buried in Beacon, New York? Contemporary accounts tell us that Chancellor Kent’s funeral took place on the 15th of December in 1847, with his internment in New York City’s Marble Cemetery following an “immense procession, consisting of Judges of our local courts, and leading members of the Bar,” according to the New York Herald. At Marble Cemetery, Kent’s body and, four years later, the remains of his wife Elizabeth Bailey, were placed in the family vault to rest there for eternity, it would seem. But the Kent connection, and the Chancellor’s eventual removal to Beacon, began in 1853, the year Judge William Kent, the Chancellor’s only son, bought “Beaconside,” his summer estate in Matteawan (now Beacon). And from the windows of Beaconside an easy view of St. Luke’s Church was to be had.

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church was designed by noted architect Frederick Clarke Withers just after the Civil War, and its grounds were laid out by its most wealthy and famous summer parishioner, Henry Winthrop Sargent, a pioneer horticulturalist and landscape gardener from Boston. Here in the village of Matteawan, in the newly adopted home of son, Chancellor Kent and his wife were to be reinterred about 25 years after his death in the beautifully landscaped setting of St. Luke’s Cemetery. In a letter written in 1873 by the church’s rector, the Rev. Henry E. Duncan, we learn of the Kent family plot:

It is a quiet burying-ground, near the village, though, removed from the bustle and noise of the community, and removed only the fourth of a mile from the foot of the somber mountains. Our beautiful stone church is only a few rods from his grave, the villagers pass on a Sunday morning along the path which conducts by grave to the north door of the edifice. The spot is retired, planted with evergreens—all that one could wish for a last home when the business of life was ended.