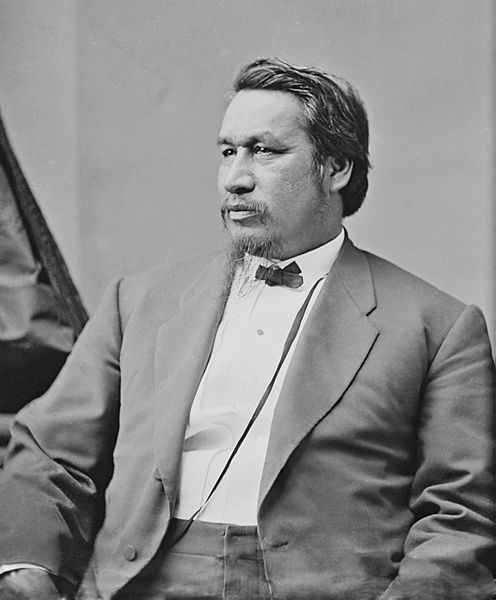

November is Native American Heritage Month, and the Society is celebrating with this biography of Ely S. Parker from our fourth Legal History by Era, Antebellum, Civil War, & Reconstruction New York: A New Court System & the Field Code, 1847-1869. Parker, a Seneca Native American, became an attorney, civil engineer, brigadier general in the Civil War, and interpreter for the Seneca people in their meetings with the federal government. He played an important role in securing land rights for the Seneca people. Due to his efforts, the Seneca people proclaimed Parker Sachem of the Six Nations. Parker is most well-known for his drafting the terms of surrender, which was signed by General Grant and General Lee and effectively ended the Civil War.

Photo: The room in the McLean House, at Appomattox C.H., in which Gen. Lee surrendered to Gen. Grant. Ely S. Parker is fifth from the right.

Ely S. Parker was born on the Seneca Reservation at Tonawanda in western New York in 1828. His parents raised him in the traditions of the League of the Haudenosaunee (also known as Six Nations or Iroquois), but also educated him at a Baptist Mission school. There, he took the first name of the school’s minister and called himself Ely Parker.

A chance meeting with the anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan greatly influenced Ely’s life — Morgan sponsored him for admission to Morgan’s alma mater, the Cayuga Academy, an elite school in Aurora, Cayuga County, in western New York. Ely encountered difficulties at the school which he described in a letter to a friend:

“Once or twice I have been severely abused. But I returned blow for blow with savage ferocity. Whether I gained the upper hand of my antagonist I leave the public to decide. For mind you, these quarrels were public. Bad business, but it could not be helped.”

The academy provided an excellent education, and the curriculum included Latin, Greek and science. Ely participated in numerous school debates and became the Academy’s leading orator. His fluency in English enabled him to become the translator, scribe, and interpreter for the Seneca elders in their meetings and correspondence with the United States government.