In the annals of criminal law, few decisions have been as important and enduring as People v. Molineux (168 NY 264 [1901]). In determining whether prior crimes may be admissible against a defendant, we speak of our “Molineux rule” and refer to “Molineux jurisprudence,” and the like. The case has been cited hundreds of times and treated in dozens of law review articles.

In authoring the opinion, Judge William E. Werner wrote the closest thing to a treatise on the subject. He laid out what, for law students and bar review candidates a century later, would develop into a mnemonic device known as “MIMIC” to help remember the Molineux exceptions authorizing the introduction of prior crimes (Motive, Intent, Absence of Mistake or Accident, Identity, and Common Scheme or Plan).1

Interestingly, the Molineux court reversed the conviction not for what we would today call a Molineux error, but because of inadmissible hearsay. Judge Werner had the foresight, however, to write an evidence tome for the guidance of future generations. It was dicta, but here we are, a hundred years later, with no end in sight, relying on Judge Werner’s teaching.2

William Edward Werner was born in Buffalo, New York, on April 19, 1855, the son of Peter and Margaret (Munderloh) Werner, both natives of Germany. At age 13, after an epidemic took both his parents, young Werner entered an iron foundry, where he worked for several years, then went to night school studying bookkeeping and commercial law at the Bryant & Stratton Business College in Buffalo.

In 1877 he moved to Rochester, where he took up the study of law in the office of W.H. Bowman, and later with Dennis C. Feeley. Two years later he served as Clerk of the Municipal Court of Rochester. In 1880 he was admitted to practice and formed a partnership with Henry J. Hetzel. Elected in 1884 as Special County Judge on the Republican ticket by the largest majority ever returned in Monroe County, Judge Werner was reelected in 1887 and two years later became County Judge. He is said to have taken a keen and sympathetic interest in young people and never sentenced young first offenders but paroled them to himself so he might guide them.3 In 1894, he was elected to State Supreme Court. While Werner was serving as a Supreme Court Justice, Governor Theodore Roosevelt elevated him to the Court of Appeals, ex officio, in 1900,4 and he served in that capacity for four years.

In 1902, he tried, unsuccessfully, to unseat Judge John C. Gray, a Democratic incumbent, but in November 1903, with bipartisan support, was elected for a full term to the Court of Appeals.5 When the Republicans and Democrats agreed on Judge Edgar M. Cullen, a Democrat, and Judge Werner, a Republican, for the 1904 election, the Albany Law Journal commended the choices and the bipartisan process that would eliminate the unseemly prospect of rough-and-tumble politics in judicial elections.6

During his 16 years on the Court, Judge Werner was prolific, writing 342 majority opinions, as against only 15 dissents and four concurrences. His most controversial decision was Ives v. South B. R. Co. (201 NY 271 [1911]), in which the Court struck down New York’s Workers’ Compensation Act. The Court denounced the law as revolutionary and unconstitutional, in that it wrongfully took property, without due process of law, from employers who are free of blame.7 Judge Werner approved of the concept of Workers’ Compensation but thought the Legislature could not enact it and that a constitutional amendment was required. Werner and the Court were not alone; Governor Charles Evans Hughes and leading legislative lawyers had doubts as to the statute’s constitutionality.8 Following the Court’s decision declaring the law unconstitutional, the Legislature amended the State Constitution in 1913, adding Article I ‘ 19 (now ‘ 18).9 The decision generated a good deal of criticism,10 most notably from Theodore Roosevelt, with whom Judge Werner previously enjoyed a warm relationship. Roosevelt bitterly attacked the Ives decision, which proved so unpopular that it may have caused Judge Werner’s defeat when he ran for Chief Judge against Judge Willard Bartlett in 1913.11 Roosevelt, then former President, and the Progressive Party opposed Judge Werner in that election because Werner had denounced the recall of judicial decisions.12 Ironically, Judge Werner wrote Ives for a unanimous Court, including Judge Bartlett. (Chief Judge Edgar M. Cullen concurred separately, emphasizing his disapproval of liability without fault and was joined by Judge Bartlett.)

Judge Werner died on March 1, 1916. His funeral was held at the Third Presbyterian Church in Rochester, and he is buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester.

Judge Werner’s landmark case, Molineux, has been a pillar of New York criminal law. In the Judge’s own eloquent words:

This rule, so universally recognized and so firmly established in all English-speaking lands, is rooted in that jealous regard for the liberty of the individual which has distinguished our jurisprudence from all others, at least from the birth of Magna Charta. It is the product of that same humane and enlightened public spirit which, speaking through our common law, has decreed that every person charged with the commission of a crime shall be protected by the presumption of innocence until he has been proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.13

Progeny

Judge Werner was survived by his wife Lillie (Boller) and three daughters, Caroline (Mrs. Frank Ernest Gannett), Clara Louise (Mrs. Hawley Ward), and Marie (Mrs. Douglas Castle Townson). Caroline, who died in 1979, and her husband Frank (1876-1957), the founder of Gannet Newspapers, had two children: Dixon Gannett, who lives in Melbourne, Florida, and Sarah Marie (1923-1985), who was a Regent of the University of the State of New York. Known as Sally, she and her husband, Charles V. McAdam had four children: Charles McAdam III, now of Scottsdale, Arizona and Vail, Colorado; Frank (Sandy) McAdam, now of Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Brooks McAdam, now of Westport, Connecticut; and Katherine McAdam Stamford, deceased.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

10 Bench and Bar (N.S.), No. 11, March 1916, p. 477 (Memoriam)

23 Green Bag 367 (1911).

29 National Cyclopedia of American Biography 142-42 (1941).

3 Chester, Courts and Lawyers of New York: A History, 1609-1925, New York, p. 1243.

64 Alb LJ 90 (1902-1903), noting the celebration of the Society of the Genesee at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, in honor of Judge Werner’s elevation to the Court of Appeals.

66 Alb LJ 311 (1904-1905).

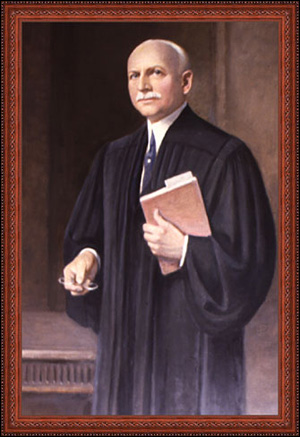

Ceremony at the Opening of Court on February 2, 1965 on the Presentation by Mrs. Frank E. Gannett of a New Portrait of Her Father, the Late William E. Werner (17 NY2d xi).

Devoy, Rochester and the Post Express: A History of the City of Rochester (1895), p. 101.

In Memoriam, 217 NY 729 (March 1, 1916).

New York Times obituary March 2, 1916, p. 10; Editorial, p. 11.

Rochester Public Library, Local History and Genealogy, in its Rochester Museum Scrapbooks, has several pages of articles relating to Judge Werner.

Roosevelt, The Outlook, Vol. 98, No. 2, p. 49, May 13, 1911.

The Political Blue Book of Rochester, N.Y., W.S. Harrison, 1903, p. 109.

University of Rochester, William E. Werner Papers.

Witt, The Passion of William Werner, The Accidental Republic, Cambridge, MA, Harvard Univ. Press, 2004, pp. 152-186. With added thanks to Columbia University Law School Professor John F. Witt for his helpful suggestions.

Published Writings

Beyond his 365 writings for the Court of Appeals (346 majority opinions), we are unaware of any published works of Judge Werner. His speech at the annual dinner of the New York State Bar Association is published, in part, in 12 Bench and Bar (N.S.), No. 2, Feb. 1908, pp. 46-48.

Endnotes

- See, e.g., People v. Rojas, 97 NY2d 32, 37 (1997); Oesby v. State, 142 Md. App. 144 (2002); Martin, Capra & Ross, New York Evidence Handbook at 4.8.6, at 239, note 99 (1997).

- For a fascinating discussion of the case, see Jonakait, People v. Molineux and Other Crime Evidence: One Hundred Years and Counting, 30 Am J Crim L 1 (2002).

- 29 National Cyclopædia of American Biography 142 (1941).

- New York Times, January 2, 1900, p. 2.

- See Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, New York, Columbia University Press (1985).

- 66 Alb LJ 302 (1904-1905); 66 Alb LJ 311 (1904-1905).

- See generally, Orth, 14 Const. Commentary 337 (1917); Vinson, Constitutional Stumbling Blocks to Legislative Tort Reform, 15 Fla St U L Rev 31 (1987).

- Betts, Roosevelt Letters, Lyons Republican Co., Lyons, N.Y., 1912, p. 78.

- See Oliver, Once is Enough: A Proposed Bar of the Injured Employee’s Cause of Action Against a Third Party, 56 Fordham L Rev 117 (1989).

- See 23 Green Bag 367 (1911). The decision also had its supporters (see, e.g., 8 Bench and Bar [N.S.], Oct. 1913, p. 87).

- Pitler, Independent State Search and Seizure Constitutionalism: The New York State Court of Appeals’ Quest for Principled Decisionmaking, 62 Brooklyn L Rev 1 (1996). The election for the Chief Judgeship was so close that it created a period of doubt and uncertainty in which Judges Werner and Bartlett each conceded and congratulated the other (7 Bench and Bar [N.S.], November 1913, p. 1). The William E. Werner Papers at the University of Rochester have a good deal of correspondence following the judicial election of 1913. An as aside, it is interesting to note that the election featured a young Learned Hand running on the Progressive Party ticket at Theodore Roosevelt’s insistence. Professor John F. Witt believes that the Republican votes for Hand may have tipped the election to Bartlett.

- New York Times obituary, March 2, 1916.

- People v. Molineux, 168 NY 264, at 291.