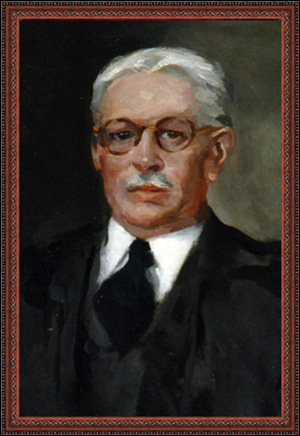

Nathan L. Miller won his first court case in his early twenties, before he was even admitted to the bar. This victory was the first of many early achievements in his distinguished career as a litigator, judge, and governor.

Miller’s great-grandfather, William Miller, arrived in the United States from the Netherlands around 1800 and settled in Amsterdam, Montgomery County, New York. Nathan Louis Miller was born on October 10, 1868 in Solon, Cortland County, New York. One of three children, his parents were Samuel Miller, a tenant dairy farmer, and Almera (Russell) Miller. The Millers moved to a farm near Groton in Tompkins County in 1872, but returned to Cortland County in 1881, settling on a farm near Cortland itself.

After graduating in 1887 from Cortland Normal School, where his favorite subjects were Latin and Mathematics, Miller became a public school teacher in neighboring villages from 1887-1893, hoping to earn enough money to attend college. The salary being insufficient for that purpose, he instead embarked upon his legal career by taking on a second job; in 1890, he entered Smith & Dickinson, a well-known Cortland firm, as a clerk. In the days before photocopiers, much of a clerk’s time was spent copying documents by hand. When the firm did not require his services, he pored over legal treatises.

Soon the firm sent Miller out to try cases in Justice Court, in which bar admission was not a prerequisite for litigation. His first case is said to have been a criminal matter. He obtained an acquittal on behalf of an African-American barber who had been accused of larceny – stealing a five-dollar gold piece while making change for a barbershop customer.1

Miller’s party affiliation was an intensely personal conviction; he became a Republican as a very young man, even though his father and paternal grandfather were Democrats. Although he participated in the debating club at Cortland Normal School, Miller’s first real introduction to public oratory occurred when a Republican meeting was to be held at West Groton, several miles from Cortland, and the announced orator did not appear on the day of the meeting. Miller was suggested to the County Republican Committee as a young school teacher who could make a speech. From that day on, he became the County Committee’s regular stump speaker.2

In 1893, Miller was admitted to the New York Bar, and in 1899 he and James F. Dougherty became partners in a law firm, Dougherty and Miller, in Cortland, where he remained until 1903. At the same time, he was increasingly active in the Republican Party, becoming Chairman of the Cortland County Republican Committee in 1898; he developed a reputation for uniting quarreling factions. From 1894 to 1900, Miller served as School Commissioner of the First District of Cortland County, visiting its rural schools to examine and license teachers, fixing the boundaries of school districts, and directing construction. Miller married Elizabeth Davern, a school principal from nearby Marathon, on November 23, 1896, and together they raised seven daughters.

In 1901-1902, Miller served as Corporation Counsel for the City of Cortland. His work as Republican County Chairman took him to the Republican State Convention and brought him to the attention of Governor Benjamin B. Odell. From 1902 to 1903, Miller was State Comptroller. Then, in November 1903, Odell appointed Miller as a Supreme Court Justice in the Sixth Judicial District. In 1905, he was designated an Associate Justice of the Appellate Division, Second Department, a position he held until 1910, when he was assigned to the Appellate Division, First Department.

While on the Appellate Division, Second Department, Miller authored the court’s opinion in Dragotto v. Plunkett, (113 AD 648 [1906]), extending a holding of the Court of Appeals that employment of a child under 14 years of age, without compliance with the child labor statutes, establishes a prima facie case of negligence on the part of the employer to children between 14 and 16 years of age. As a consequence, the employment of children aged 14 to 16 in dangerous occupations became less common.

Miller remained on the First Department until December 1912, when Chief Judge Edgar M. Cullen of the Court of Appeals requested that incoming Governor William Sulzer appoint Miller to the Court of Appeals. Both Chief Judge Cullen and Governor Sulzer were Democrats. Miller commenced his term on the Court of Appeals on January 13, 1913.

During his brief time on the Court, one of Miller’s best-known opinions was Matter of Jensen v. Southern Pacific Co. (215 NY 514 [1915]), in which the Court upheld the constitutionality of the Workmen’s Compensation Law of 1914 against Commerce Clause and Fourteenth Amendment Takings Clause challenges. Jensen was a stevedore who died in an accident on a gangway about 10 feet seaward of a pier in New York City, while unloading a steamship owned by the defendant company, his employer. The lower court affirmed the award of the state workers’ compensation commission, and the employer appealed. After upholding the 1914 law as a valid exercise of the state’s police power, Miller commented on its fundamental fairness:

This subject should be viewed in the light of modern conditions, not those under which the common law doctrines were developed. With the change in industrial conditions, an opinion has gradually developed, which almost universally favors a more just and economical system of providing compensation for accidental injuries to employees as a substitute for wasteful and protracted damage suits, usually unjust in their results either to the employer or the employee, and sometimes to both. Surely it is competent for the state in the promotion of the general welfare to require both employer and employee to yield something toward the establishment of a principle and plan of compensation for their mutual protection and advantage.3

The matter was appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which reversed in a 5-4 decision, on the ground that the statute, as applied to a stevedore working over navigable waters at the time of the accident, infringed upon federal jurisdiction over admiralty and maritime questions (Southern Pacific Co. v. Jensen, 244 US 205 [1917]). Congress ultimately extended federal protection to shore-based workers injured while temporarily over navigable waters.

In Davies v. Delaware, L. & W. R. Co. (215 NY 181 [1915]), the plaintiff’s premises, which abutted a railroad track, were set on fire by sparks emitted either from the smokestacks of the railroad company’s engines or from coals dropped from the engines onto the tracks. The fire destroyed two buildings, as well as lumber and shingles. Counsel for the railroad company persuaded the trial court that there could be no liability, for the destruction of the further building, if the fire were communicated from one building to another on the plaintiff’s property, rather than directly from the railroad track. Writing for a unanimous court, Miller clarified the well-settled law that a railroad company is not liable to the owner of lands that do not adjoin its premises, for damages caused by fire communicated through intervening abutting land. He pointed out that only the intervening land of a third person could sever the causal connection needed for liability. “In this case there was no intervening property between the plaintiff’s lands and those of the railroad . . . The mere fact that the fire may have spread from one building to the other, or from the buildings to the lumber, did not break the causal connection between the defendant’s negligence and the entire damage done.”4

Middleton v. Whitridge (213 NY 499 [1915]), another of Miller’s opinions for the Court, stands for the proposition that if a carrier’s employees know or should know that a passenger is seriously ill and in need of attention, it is their duty to give the passenger first aid and to ensure that he is put in the custody of those who can take care of him. In Middleton, the passenger, showing no signs of sickness or intoxication, boarded a streetcar, suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, and was carried past his station in a helpless condition. The conductor, assuming him to be drunk, permitted him to remain on the car for several hours although he continued to vomit continuously and show signs of incontinent urination. The case, vividly described in Miller’s clear prose, became the source of an illustration in the Restatement of Torts.

In People v. Griswold, (213 NY 92 [1914]), Miller wrote for the Court in upholding the constitutional validity of a Public Health Law statute that prohibited the practice of dentistry without a license and affirming a conviction for unlicensed practice where the defendant was licensed in Kansas and Utah, but not New York. In doing so, Miller noted that the test to be applied, in assessing whether the law was a valid exercise of the state’s police power, was a test of fitness for intended end, rather than a test of overall wisdom or propriety.

In determining whether statutory requirements are arbitrary, unreasonable or discriminatory, it must be borne in mind that the choice of measures is for the legislature, who are presumed to have investigated the subject, and to have acted with reason, not from caprice. Legislation passed in the exercise of the police power must be reasonable in the sense that it must be based on reason as distinct from being wholly arbitrary or capricious, but when the legislature has power to legislate on a subject, the courts may only look into its enactment far enough to see whether it is in any view adapted to the end intended. If it is, the court must give it effect, however unwise they may regard it, or however much they might, if given the choice, prefer some other measure as more fit and appropriate.5

Miller’s elegant statement of the rational basis test was quoted in many jurisdictions.

Two and a half years after he joined the Court, on August 1, 1915, Miller resigned, to begin corporate law practice in Syracuse, citing Mrs. Miller and their seven daughters as eight reasons why he needed to earn more money than the judicial salary of $13,700. Initially he worked as general counsel to the Solvay Process Company. He continued to be involved at the highest levels of Republican Party politics, accepting appointment to the Executive Committee of the Republican State Committee in 1920. In the same year, as a Delegate at Large to the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Miller made the nominating speech for Herbert Hoover. He was also President of the State Bar Association in 1920-1921.

Miller and his wife entertained regularly at their house in Syracuse. Interviewed in 1920, Mrs. Miller noted: “We always have guests. Anywhere from thirteen to eighteen people sit down at our table each day.”6

After addressing some of his financial concerns in corporate law practice in Syracuse, Miller somewhat reluctantly entered the gubernatorial race and defeated incumbent Democrat Alfred E. (Al) Smith in the 1920 election, despite the latter’s very strong showing in New York City. Miller ran on a conservative, cost-cutting platform. He had long been a supporter of limited government. In his stump speeches, he insisted that “[t]he State should never undertake to do what the citizens can do as well or better.”7 He spoke out against what he saw as federal encroachment on state power, but attracted “dry” votes by insisting that he supported the enforcement of Prohibition, now that it was the law.8 He rejected proposed welfare legislation as paternalism. In international affairs, he spoke in opposition to the League of Nations, on the ground that American troops would be sent to foreign wars.

Miller served as the 43rd Governor of New York in 1921-1922 (a two-year term was in effect at the time). As of the time of writing, he is often cited as the last true “upstate” candidate to win the election for governor.9 Miller, the “economy governor,”10 is probably better known for his term as a cost-cutting state leader than for his time on the Court of Appeals. Upon receiving budget estimates of $206 million from his predecessor, Miller reduced annual expenditure to $130 million in 1921 and kept it there in 1922, abolishing many state jobs he considered superfluous. Miller claimed that he saved taxpayers $20 million during his two years in office.

While Governor, Miller devised the law establishing the New York City Transit Commission and reformed the City’s complex Interborough Rapid Transit. He created a State Department of Purchase and Supply, and ended Albany’s private monopoly on public printing. He altered the management of state prison industries (allowing for prisoners’ net earnings to be paid to their families or to the prisoners themselves upon their release), and began a custom of annually requesting prison wardens and chaplains to submit names of prisoners they considered worthy of executive clemency. He promoted child hygiene clinics, and the use of water power as electricity. Believing that his efforts to economize in state government should begin at home, Miller personally paid for all repairs and renovations at the Governor’s Mansion.

When Miller became governor, women had just earned the right to vote. Prior to his election, he had told the Republican Women’s State Executive Committee that he “look[ed] forward to the time when the question of sex will be entirely eliminated in political affairs and persons will be elected to public office not because they are men or women but because of their particular fitness.”11 Once governor, however, he rendered himself controversial when he delivered a speech at the League of Women Voters’ annual dinner. He advised the 300 women in the audience, “there is no proper place for a League of Women Voters, precisely as I should say there was no proper place for a League of Men Voters. . . . And I have a very firm conviction that any organization (that) seeks to exert political power is a menace to our institutions, unless it is organized as a political party.”12

Miller’s rigorous cost-cutting measures cost him popularity and he was not reelected. His unsuccessful 1922 campaign continued to center on themes of economic reform and “Wastefulness Blotted Out.”13 Miller declared that “[s]pecial Interests have marched down Capitol Hill empty-handed under my administration.”14 Though he had defeated Al Smith in 1920, Smith defeated Miller in 1922 by a half a million votes, much of the state voting Democratic that year. Miller wired Smith his concession: “Having tried both our brands of government, the people have chosen yours. Congratulations.”15 It was twenty years before the next Republican Governor of New York.

After he lost his reelection campaign, Miller joined Harold Otis in private practice in New York City, to form the partnership Miller & Otis, which joined with Hornblower, Miller & Garrison in 1931. (William B. Hornblower [1851-1914], a founding partner of the latter firm, served on the Court of Appeals for a short time in 1914.) The merged firm later became Willkie, Farr & Gallagher.

As his term as governor was about to end, Miller learned that Chief Justice William H. Taft intended to recommend to the President that Governor Miller be appointed as an Associate Justice to the United States Supreme Court. Remarkably, Miller declined the offer on the ground that he had already agreed to enter into a law partnership with Otis in New York.

From 1925 until his death, Miller served as general counsel, a director, and a finance committee member of the United States Steel Corporation. This work took much of Miller’s time and he left Hornblower, Miller & Garrison in 1939. Over the years he was frequently retained as counsel by other lawyers, becoming known as a “lawyer’s lawyer.”16 In the mid-1930s, the Millers bought an estate at Oyster Bay on Long Island, which became their summer home.

In 1952, the United States Steel Corporation, counseled by Miller, was one of several victorious steel companies in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case of Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (343 US 579 [1952]). Miller was on the brief. In January that year, Miller was the first recipient of the New York State Bar Association’s Gold Medal “For Distinguished Service to the Legal Profession.”17 The President of the Bar Association spoke of Miller as a “distinguished, able and brilliant lawyer” and noted that Miller’s biography was a “complete bill of particulars of the outstanding service” he had rendered to the public and the profession, as well as the Association itself.18 Miller also received honorary LL.D. degrees from Columbia University, Syracuse University, Colgate University, and Union College.

Golf and bridge were favorite recreational activities. Miller remained a friend of Chief Judge Frank H. Hiscock after leaving the Court of Appeals, and in 1920 the two vacationed together in New Hampshire to play golf. After he won the gubernatorial election that year, Miller and his wife celebrated with a ten-day vacation at a golf club near Atlantic City.

After a lengthy career in which he played many different legal roles, Miller died at the age of 86, on June 26, 1953, in the Millers’ suite at The Pierre in New York. He had suffered a debilitating hip fracture in a fall the previous month, and died of pneumonia. Roughly 250 people attended his funeral at St. Vincent Ferrer Roman Catholic Church in New York. He is buried at the Cortland Rural Cemetery. Miller left his tangible personal property to his widow, and his seven daughters inherited the bulk of his estate. At the time of his death, he and his wife had 23 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren.

Progeny

Miller and his wife had seven daughters. Mildred M. Miller married Dennis Percy McCarthy, and they had four children: Mary Elizabeth (Betty) Coffin, of Lenox, Massachusetts; Mildred (Milly) Riemenschneider, of Santa Barbara, California; Marian Patricia (Pat) Korry, of Charlotte, North Carolina; and Nathan McCarthy. Marian M. Miller married Marcel Pierre Labourdette, and they had four children: Mimi Labourdette, of High Falls, New York; Margaret (Margy) Garesche, of Chappaqua, New York; Nelly Hopkins, of Cazenovia, New York; and Peter Labourdette. Margaret M. Miller married George Bogart Blakely, and they had a daughter, Barbara. Elizabeth M. Miller married Alvin Phillip Adams, and they had three children: Didi Adams Kiggen, of New York City; Alvin Adams, Jr., of Honolulu; and Nathan Adams, of Ennis, Montana. Louise M. Miller married Douglas Robinson, and they had four children: Lynne Brookfield of Charlottesville, Virginia; Nora Robinson Stark, of Tucson, Arizona; Edward Robinson; and Douglas Robinson, Jr., of Tucson, Arizona. Eleanor M. Miller married Francis Terence Carmody, and they had three children: Elizabeth (Liz) Barens, of Oyster Bay, New York; Paul Carmody, of New York City; and Terry Carmody. Constance M. Miller married Walter K. Phelps, and they had four children, Michael Phelps, of Berkeley, California; Timothy Phelps, of Washington, D.C.; Kane Phelps, of Pacific Palisades, California; and Richard (Dick) Phelps, of India Atlantic, Florida.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Collected correspondence of Governor Nathan L. Miller, Syracuse University Library.

“The Constitution and Modern Trends,” 10 Bar Briefs 176 (1933-1934).

Correspondence with Mary Coffin, Lenox, MA.

Cortland County Historical Society.

The Cortland Standard.

In Memoriam, 306 NY xi, xiii (1954).

Kirst, “A Portrait of Upstate’s Last Governor,” Post-Standard (Syracuse, NY), February 11, 2002, p. B-1.

MacAdam, “The Real Governor Miller,” The New York Times Magazine, October 15, 1922.

The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Vol. 43, at 53-54 (1961).

The New York Times.

Riemenschneider, In Service of Their God, Their Country, and Their Neighbors, at 110-120.

Taylor, Eminent Members of the Bench and Bar of New York (1943).

Union College.

Published Writings Include:

Recollections (1953).

American Bar Association Journal, Vol. 34 (November 1948).

Public Papers of Nathan L. Miller: 1922 (1924).

Public Papers of Nathan L. Miller: 1921 (1924).

“Pressing Problems of Government,” New York State Bar Association Proceedings of the Forty-Fourth Annual Meeting held at New York, January 21-22, 1921 (Presidential Address).

Endnotes

- See MacAdam, “The Real Governor Miller,” New York Times Magazine, October 15, 1922.

- See id.

- 215 NY 514, 528.

- 215 NY 181, 184.

- 213 NY 92, 96-97.

- “Daughters May Aid Miller’s Candidacy,” New York Times, September 12, 1920, p. W14.

- “[Miller] Says State Can Cure Ills,” New York Times, September 3, 1920, p. 3.

- See e.g. “Republican Women Hear Mrs. Miller,” New York Times, October 26, 1920, p. 17.

- Kirst, “A Portrait of Upstate’s Last Governor,” Post-Standard (Syracuse, NY), February 11, 2002, p. B-1.

- See e.g. “Smith Denounces Miller as Servant of ‘Big Interests,'” New York Times, October 6, 1922, p. 1.

- “Women Aids Hear Miller,” New York Times, September 21, 1920, p. 8.

- “Miller Tells League of Women Voters It is a Menace to Our Institutions, Attacks Its Social Welfare Program,” New York Times, January 28, 1921, p. 1.

- “Wastefulness Blotted Out,” Nathan L. Miller gubernatorial re-election leaflet, Cortland County Historical Society.

- Id.

- “Miller — ‘Smith Brand of Government Chosen’; Smith — ‘I Am Grateful and Hope I Make Good,'” New York Times, November 8, 1922, p. 4.

- See e.g. “State Bar Association Honors Nathan Miller,” Syracuse Herald-Journal, December 6, 1951; “Ex-Gov. Miller Dies Here at Age of 84,” New York Times, June 27, 1953, p. 15.

- “Former Governor Miller, Now 83, Wins State Bar Association Award,” New York Times, December 6, 1951, p. 35.

- See In Memoriam, 306 NY xi, xiii (1954).