Description

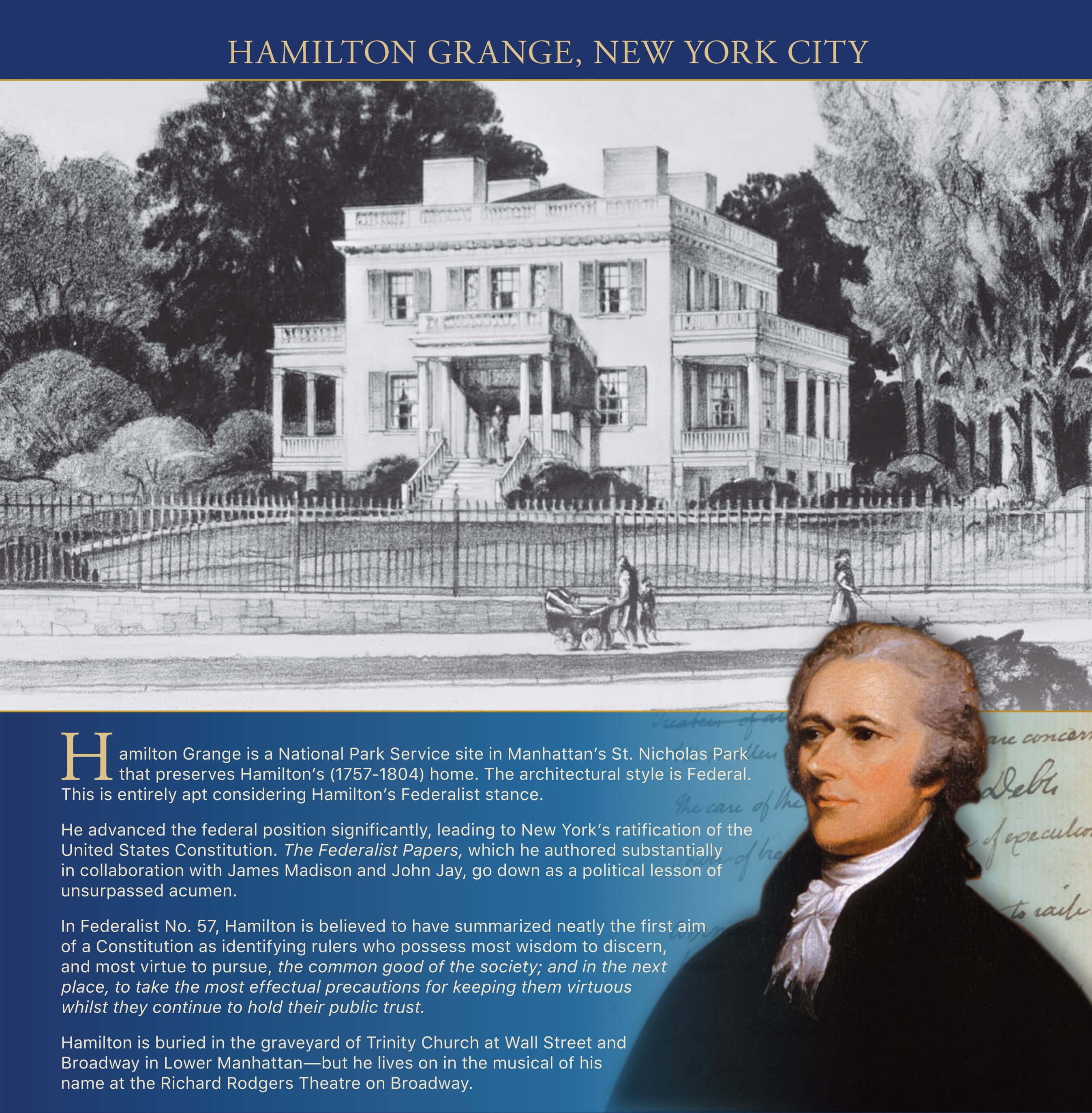

Hamilton Grange, New York City

Hamilton Grange is a National Park Service site in Manhattan’s St. Nicholas Park that preserves Hamilton’s home. The architectural style is Federal. This is entirely apt considering Hamilton’s Federalist stance.

He advanced the federal position significantly, leading to New York’s ratification of the United States Constitution. The Federalist Papers, which he authored substantially in collaboration with James Madison and John Jay, go down as a political lesson of unsurpassed acumen.

In Federalist No. 57, Hamilton is believed to have summarized neatly the first aim of a Constitution as identifying rulers who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue, the common good of the society; and in the next place, to take the most effectual precautions for keeping them virtuous whilst they continue to hold their public trust.

Hamilton is buried in the graveyard of Trinity Church at Wall Street and Broadway in Lower Manhattan—but he lives on in the musical of his name at the Richard Rodgers Theatre on Broadway.

Images:

Portrait of Alexander Hamilton, painted by John Trumbull, c. 1805. Courtesy of White House Collection/White House Historical Collection

Drawing of the Hamilton Grange by OH.F. Langmann. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, Survey Number: HABS NY-6335

Alexander Hamilton’s notes for a speech proposing a plan of government at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Alexander Hamilton Papers

February 2019

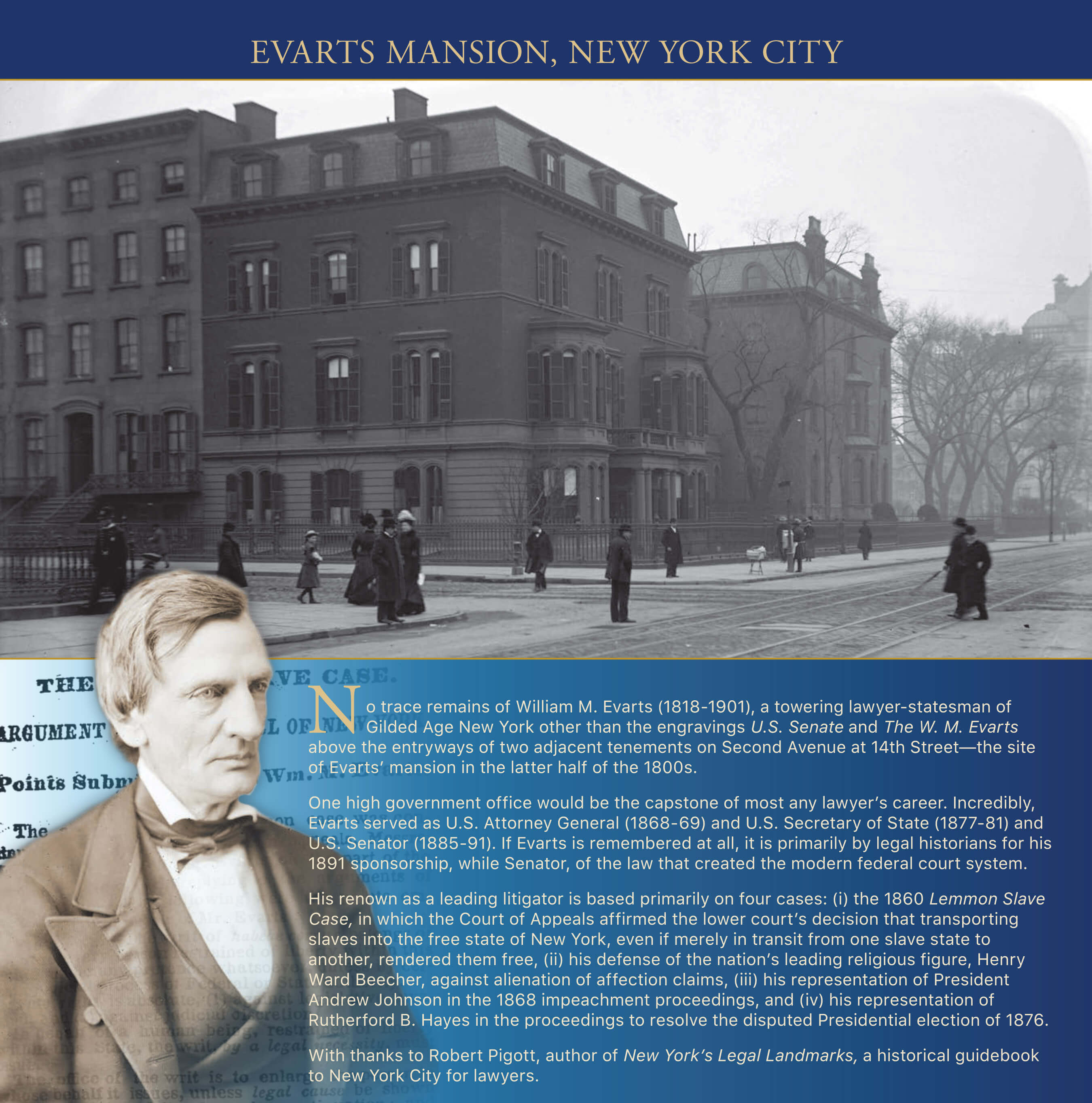

William M. Evarts House, New York City

No trace remains of William M. Evarts, a towering lawyer-statesman of Gilded Age New York other than the engravings U.S. Senate and The W. M. Evarts above the entryways of two adjacent tenements on Second Avenue at 14th Street—the site of Evarts’ mansion in the latter half of the 1800s.

One high government office would be the capstone of most any lawyer’s career. Incredibly, Evarts served as U.S. Attorney General (1868-69) and U.S. Secretary of State (1877-81) and U.S. Senator (1885-91). If Evarts is remembered at all, it is primarily by legal historians for his 1891 sponsorship, while Senator, of the law that created the modern federal court system.

His renown as a leading litigator is based on four cases: (i) the 1860 Lemmon Slave Case, in which the Court of Appeals affirmed the lower court’s decision that transporting slaves into the free state of New York, even if merely in transit from one slave state to another, rendered them free, (ii) his defense of the nation’s leading religious figure, Henry Ward Beecher, against alienation of affection claims, (iii) his representation of President Andrew Johnson in the 1868 impeachment proceedings, and (iv) his representation of Rutherford B. Hayes in the proceedings to resolve the disputed Presidential election of 1876.

With thanks to Robert Pigott, author of New York’s Legal Landmarks, a historical guidebook to New York City for lawyers.

Images:

Portrait of William M. Evarts, c. 1860s. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-cwpbh-05064

William Evarts’ Mansion on the northwest corner of 14th Street and Second Avenue. Collection of the New-York Historical Society, Robert L. Bracklow Photograph Collection, 66000-1418

The New York Times, January 26, 1860. Copyright The New York Times

March 2019

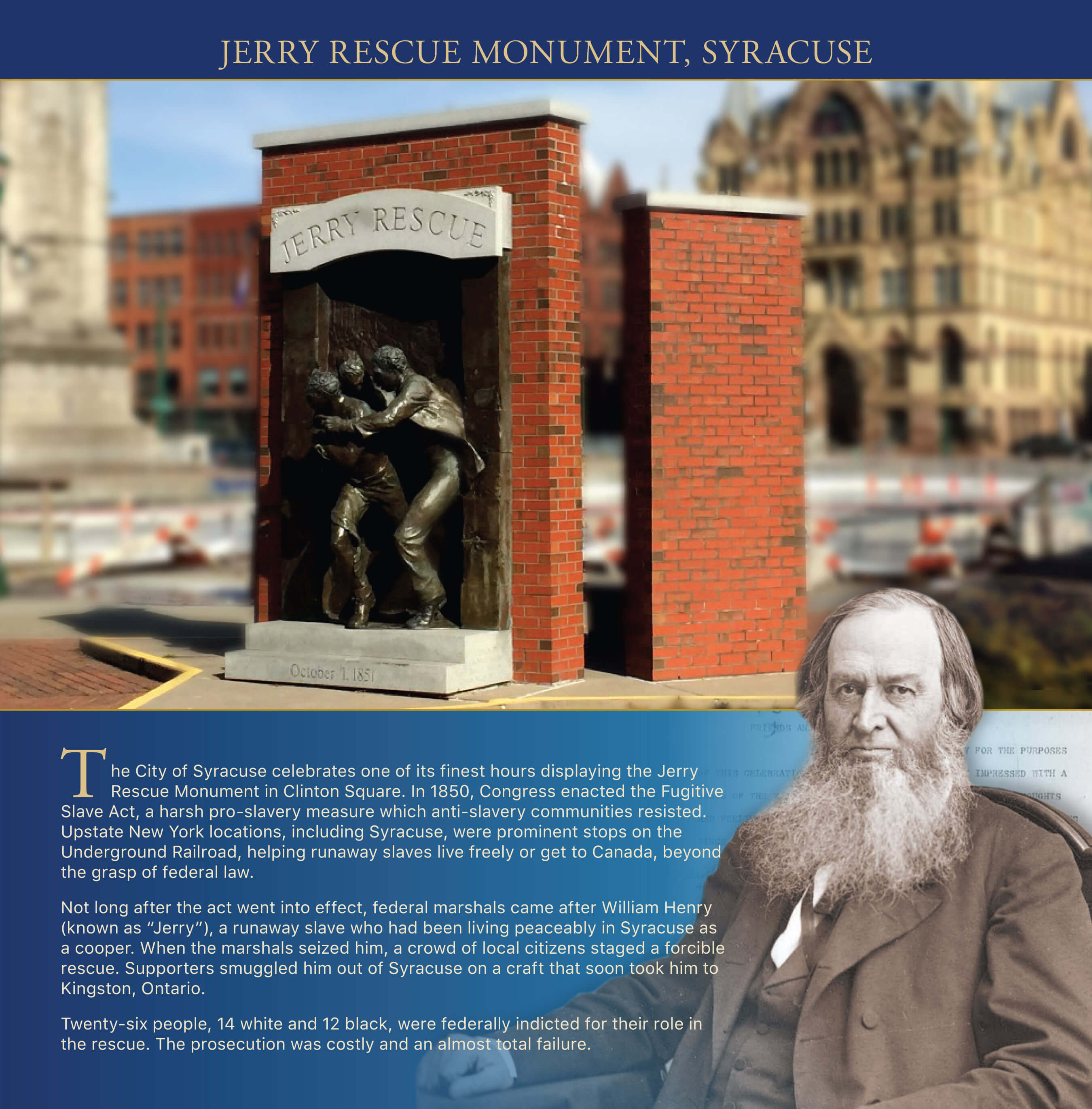

The Jerry Rescue Monument, Syracuse

The City of Syracuse celebrates one of its finest hours displaying the Jerry Rescue Monument in Clinton Square. In 1850, Congress enacted the Fugitive Slave Act, a harsh pro-slavery measure which anti-slavery communities resisted. Upstate New York locations, including Syracuse, were prominent stops on the Underground Railroad, helping runaway slaves live freely or get to Canada, beyond the grasp of federal law.

Not long after the act went into effect, federal marshals came after William Henry (known as “Jerry”), a runaway slave who had been living peaceably in Syracuse as a cooper. When the marshals seized him, a crowd of local citizens staged a forcible rescue. Supporters smuggled him out of Syracuse on a craft that soon took him to Kingston, Ontario.

Twenty-six people, 14 white and 12 black, were federally indicted for their role in the rescue. The prosecution was costly and an almost total failure.

Images:

Portrait of Gerrit Smith, an organizer of the Liberty Part, which was having a convention when the Jerry Rescue occurred. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, LC-DIG-cwpbh-02631

Photograph of the Jerry Rescue Monument in Clinton Square, Syracuse, 2017. Credit Chris Bolt, WAER.org

Fredrick Douglass’s speech on the 33rd anniversary of the Jerry Rescue in Rochester, NY. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Frederick Douglass Papers at the Library of Congress

April 2019

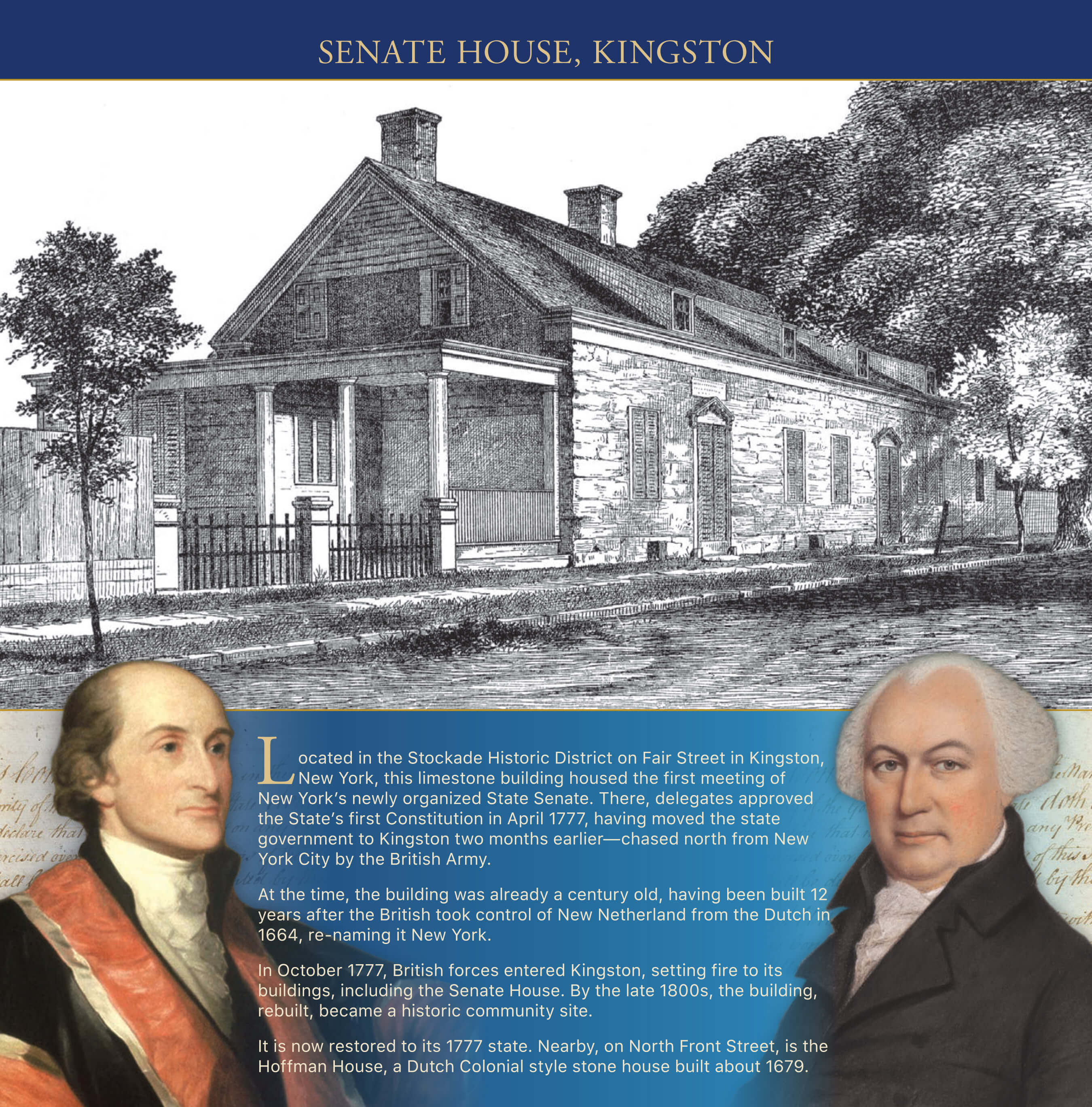

Senate House, Kingston

Located in the Stockade Historic District on Fair Street in Kingston, New York, this limestone building housed the first meeting of New York’s newly organized State Senate. There, delegates approved the State’s first Constitution in April 1777, having moved the state government to Kingston two months earlier—chased north from New York City by the British Army.

At the time, the building was already a century old, having been built 12 years after the British took control of New Netherland from the Dutch in 1664, re-naming it New York.

In October 1777, British forces entered Kingston, setting fire to its buildings, including the Senate House. By the late 1800s, the building, rebuilt, became a historic community site.

It is now restored to its 1777 state. Nearby, on North Front Street, is the Hoffman House, a Dutch Colonial style stone house built about 1679.

Images:

Portrait of John Jay, an author of the first New York State Constitution, painted by Gilbert Stuart, 1794, oil on canvas. Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington

Portrait of Gouverneur Morris, an author of the first New York State Constitution, painted by James Sharples, 1810, pastel on paper. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Miss Ethel Turnbull in memory of her brothers, John Turnbull and Gouverneur Morris Wilkins Turnbull

A print of the Senate House in Kingston, NY. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library

A handwritten page of the first New York State Constitution, 1777. Courtesy of New York State Archives, Series A1802-78

May 2019

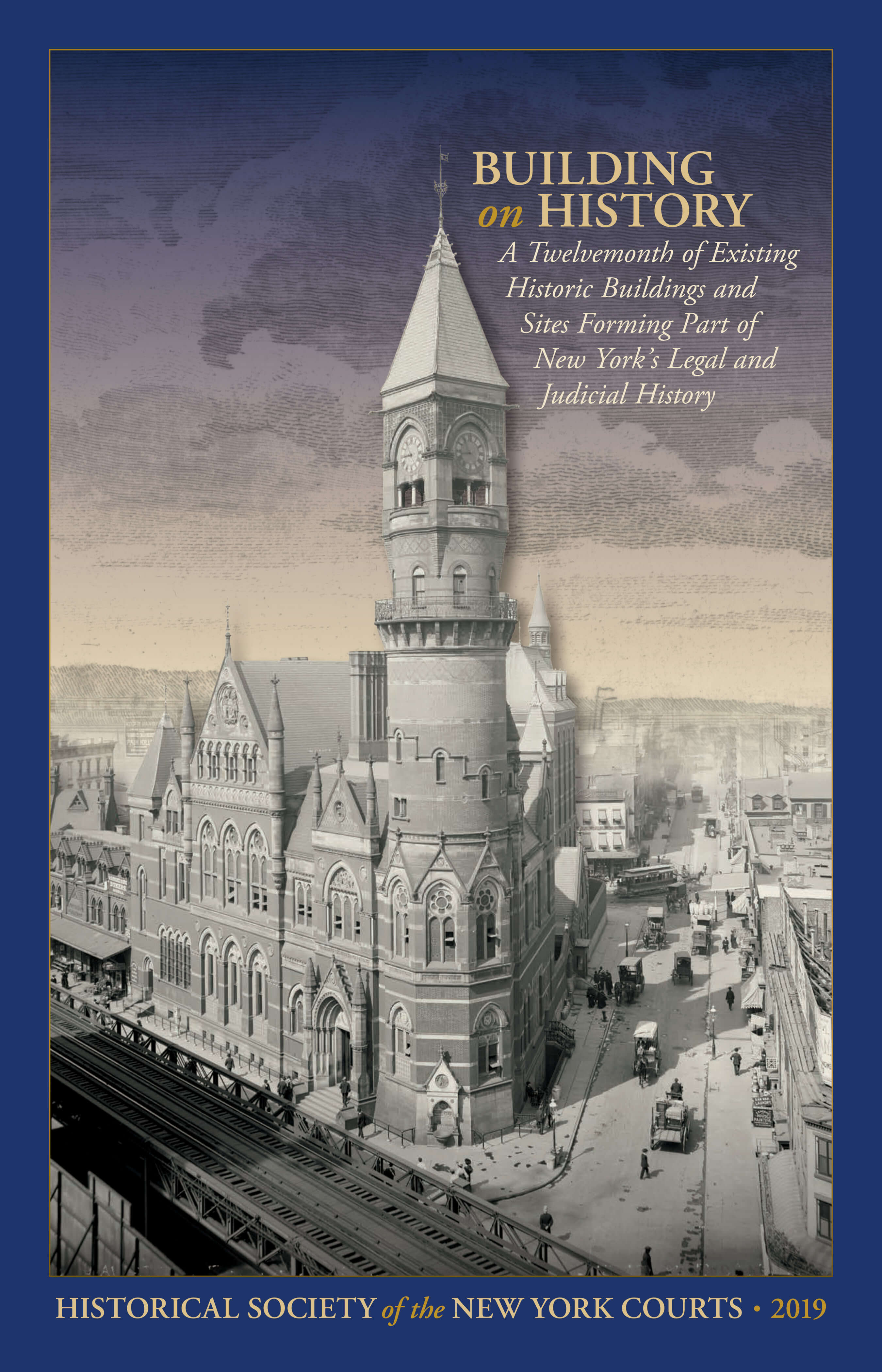

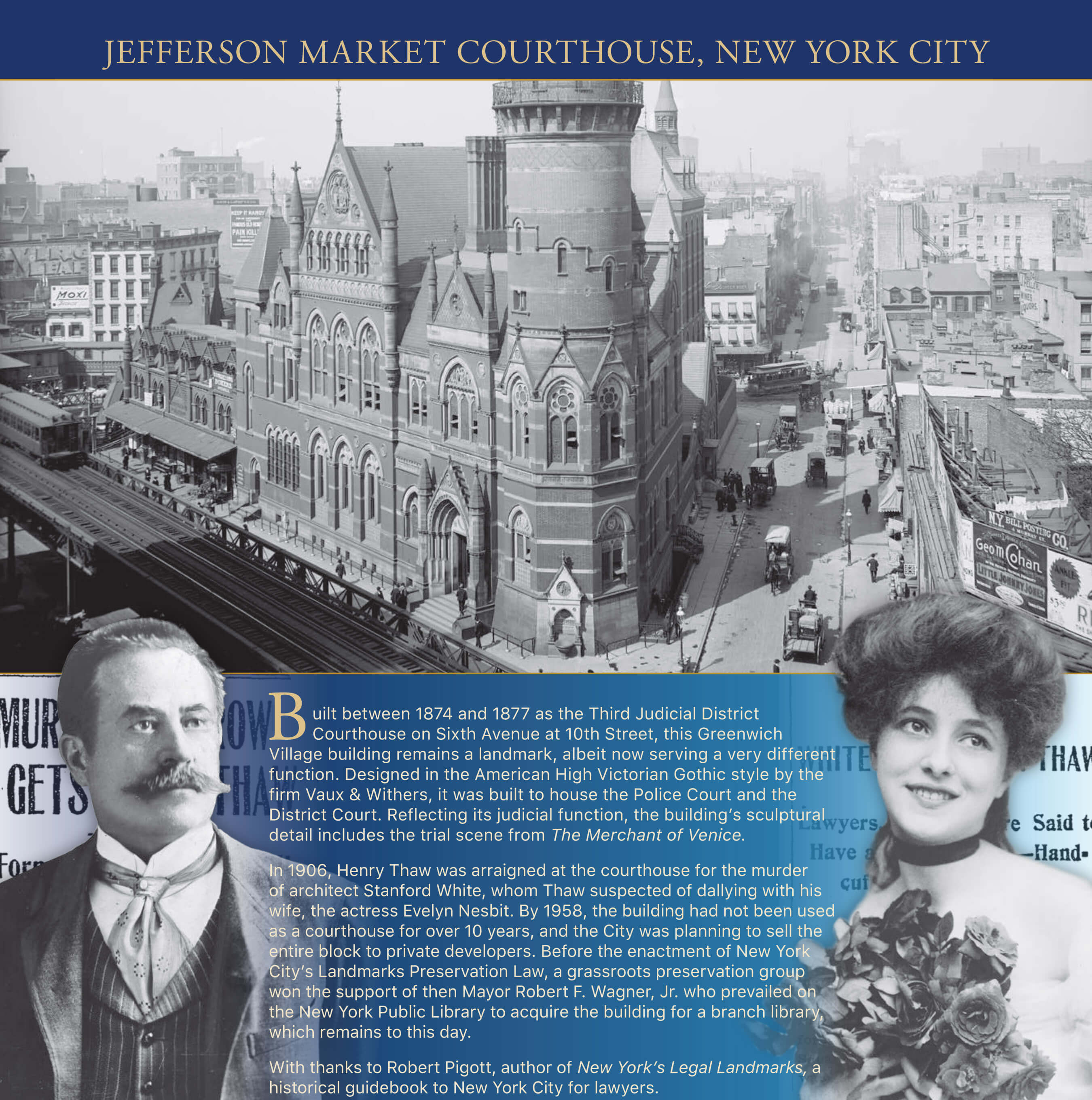

Jefferson Market Courthouse, New York City

Built between 1874 and 1877 as the Third Judicial District Courthouse on Sixth Avenue at 10th Street, this Greenwich Village building remains a landmark, albeit now serving a very different function. Designed in the American High Victorian Gothic style by the firm Vaux & Withers, it was built to house the Police Court and the District Court. Reflecting its judicial function, the building’s sculptural detail includes the trial scene from The Merchant of Venice.

In 1906, Henry Thaw was arraigned at the courthouse for the murder of architect Stanford White, whom Thaw suspected of dallying with his wife, the actress Evelyn Nesbit. By 1958, the building had not been used as a courthouse for over 10 years, and the City was planning to sell the entire block to private developers. Before the enactment of New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Law, a grassroots preservation group won the support of then Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. who prevailed on the New York Public Library to acquire the building for a branch library, which remains to this day.

With thanks to Robert Pigott, author of New York’s Legal Landmarks, a historical guidebook to New York City for lawyers.

Images:

Portrait of Stanford White, 1900. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ds-10592

Portrait of Evelyn Nesbit, 1901. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-113759

Photograph of the Jefferson Market Courthouse, 1905. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-det-4a12681

The New York Times, June 27, 1906. Copyright The New York Times

June 2019

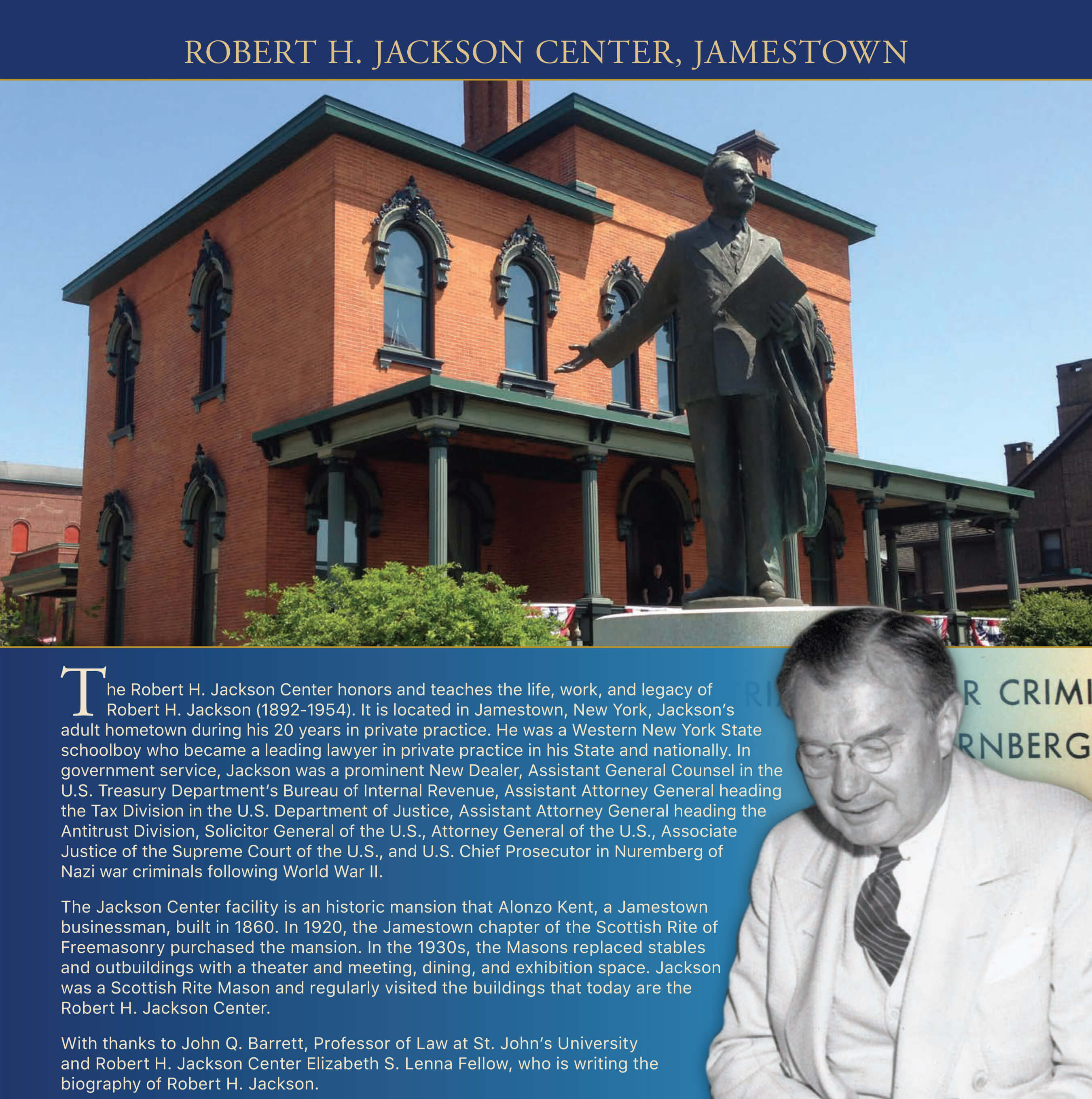

The Robert H. Jackson Center, Jamestown

The Robert H. Jackson Center honors and teaches the life, work, and legacy of Robert H. Jackson (1892-1954). It is located in Jamestown, New York, Jackson’s adult hometown during his 20 years in private practice. He was a Western New York State schoolboy who became a leading lawyer in private practice in his State and nationally. In government service, Jackson was a prominent New Dealer, Assistant General Counsel in the U.S. Treasury Department’s Bureau of Internal Revenue, Assistant Attorney General heading the Tax Division in the U.S. Department of Justice, Assistant Attorney General heading the Antitrust Division, Solicitor General of the U.S., Attorney General of the U.S., Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the U.S., and U.S. Chief Prosecutor in Nuremberg of Nazi war criminals following World War II.

The Jackson Center facility is an historic mansion that Alonzo Kent, a Jamestown businessman, built in 1860. In 1920, the Jamestown chapter of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry purchased the mansion. In the 1930s, the Masons replaced stables and outbuildings with a theater and meeting, dining, and exhibition space. Jackson was a Scottish Rite Mason and regularly visited the buildings that today are the Robert H. Jackson Center.

With thanks to John Q. Barrett, Professor of Law at St. John’s University, who is writing the biography of Robert H. Jackson.

Images:

Jackson reports to President Harry S. Truman in the Oval Office on the completed London negotiations and upcoming Nuremberg trial, 1945. Credit: Harry S. Truman Library & Museum

Photograph of the Robert H. Jackson Center with the statue of Justice Jackson, 2016. Courtesy of the Robert H. Jackson Center

The Opening Address for The United States of America by Hon. Robert H. Jackson at the Trial of War Criminals at Nuernberg. © 1946, The Washington Post

July 2019

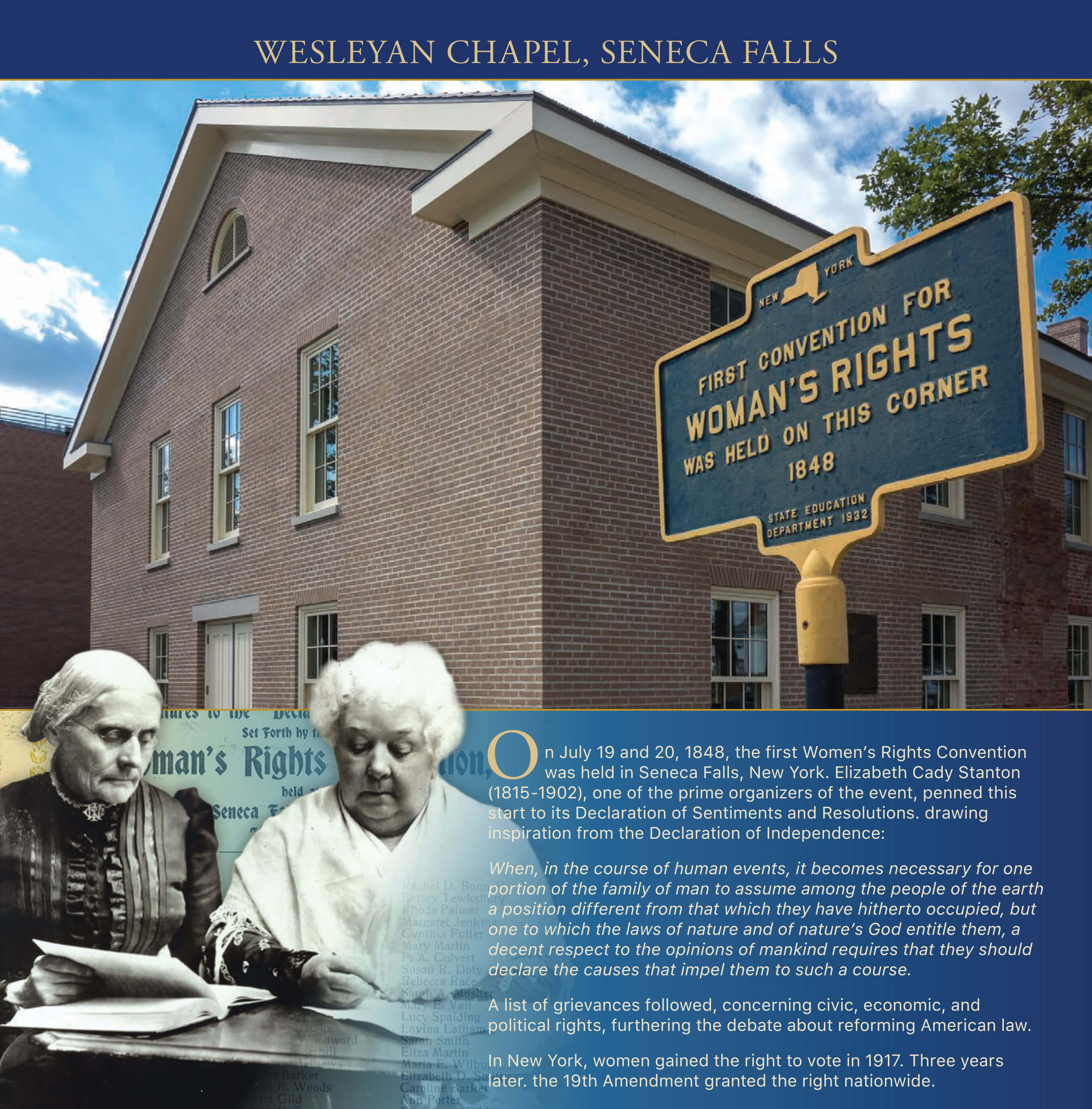

Wesleyan Chapel, Seneca Falls

On July 19 and 20, 1848, the first Women’s Rights Convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, one of the prime organizers of the event, penned this start to its Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions. drawing inspiration from the Declaration of Independence:

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.

A list of grievances followed, concerning civic, economic, and political rights, furthering the debate about reforming American law.

In New York, women gained the right to vote in 1917. Three years later. the 19th Amendment granted the right nationwide.

Images:

Portrait of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 1891. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party, Group I, Container I:159, Folder: Anthony, Susan B. and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Modern-day photograph of the Wesleyan Chapel, 2013. Creative Commons Image courtesy of Kenneth C. Zirkel

The honor roll, listing the women and men who signed the Declaration of Sentiments at the first Women’s Rights Convention, 1848. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection, JK1881 .N357 sec. XVI, no. 3-9 NAWSA Coll

August 2019

Governors Island, New York City

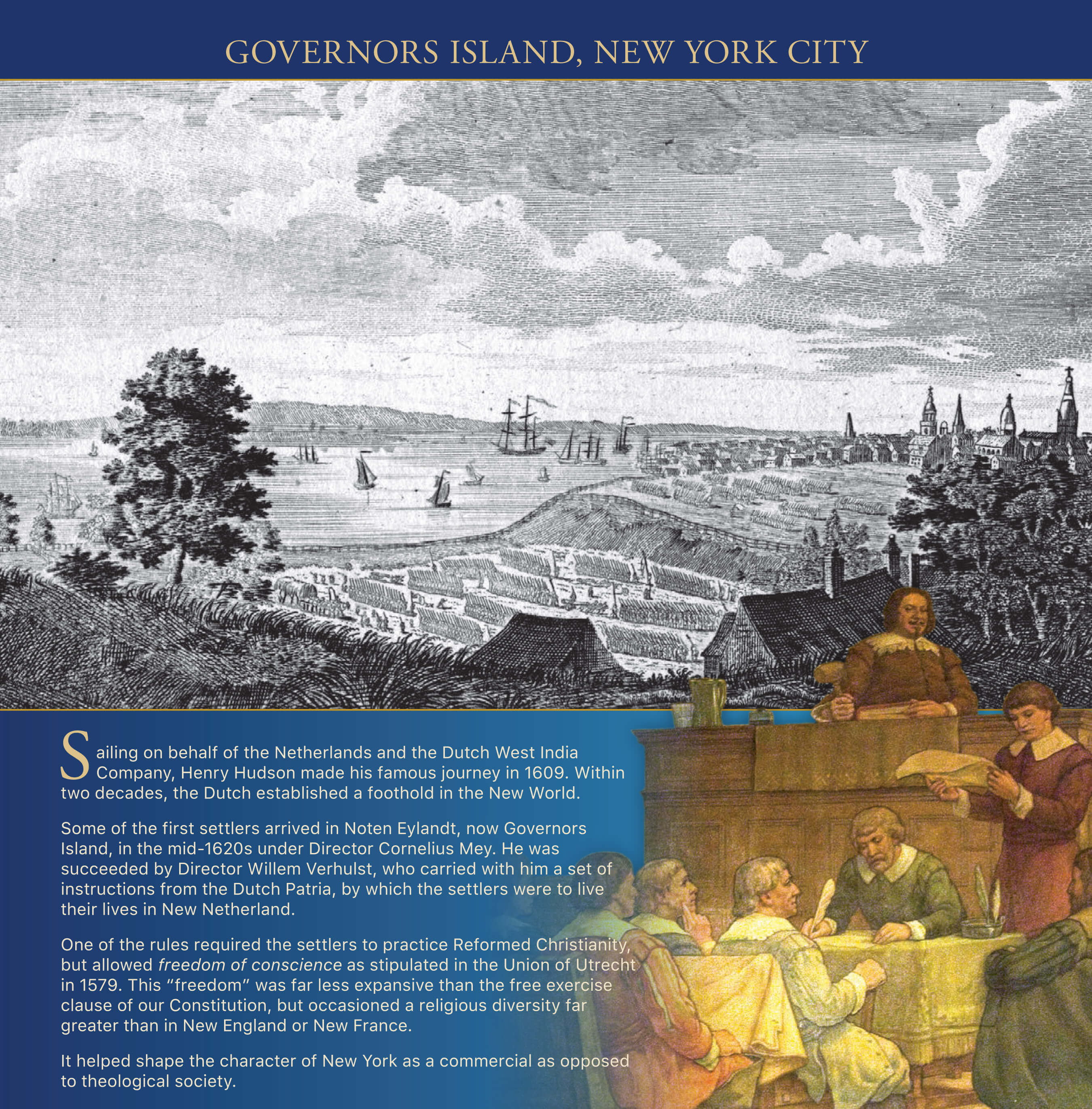

Sailing on behalf of the Netherlands and the Dutch West India Company, Henry Hudson made his famous journey in 1609. Within two decades, the Dutch established a foothold in the New World.

Some of the first settlers arrived in Noten Eylandt, now Governors Island, in the mid-1620s under Director Cornelius Mey. He was succeeded by Director Willem Verhulst, who carried with him a set of instructions from the Dutch Patria, by which the settlers were to live their lives in New Netherland.

One of the rules required the settlers to practice Reformed Christianity, but allowed freedom of conscience as stipulated in the Union of Utrecht in 1579. This “freedom” was far less expansive than the free exercise clause of our Constitution, but ocasioned a religious diversity far greater than in New England or New France.

It helped shape the character of New York as a commercial as opposed to theological society.

Images:

Meeting of the first popular law court of New Netherland in the City Hall of New Amsterdam. Mural in the ceremonial courtroom at New York County Courthouse, 60 Centre Street, NY, NY. Photo by Teodors Ermansons

New York City, Governors Island, and the River from Long Island, 1776. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library

Article 2 of the Provisional Regulations for Colonists, given to Director Willem Verhulst, 1626. HM 548, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

September 2019

Chester A. Arthur Home, New York City

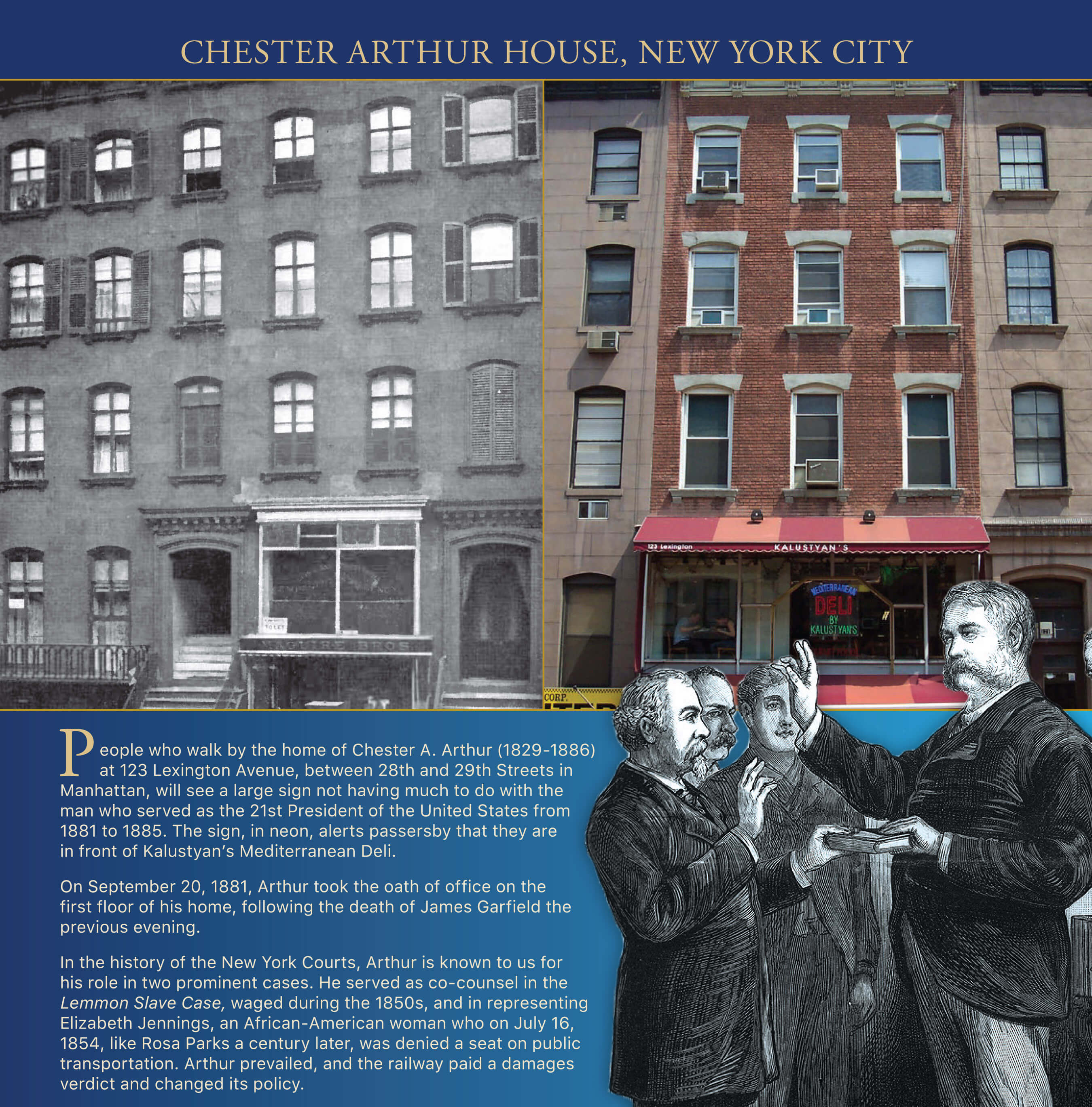

People who walk by the home of Chester A. Arthur (1829-1886) at 123 Lexington Avenue, between 28th and 29th Streets in Manhattan, will see a large sign not having much to do with the man who served as the 21st President of the United States from 1881 to 1885. The sign, in neon, alerts passersby that they are in front of Kalustyan’s Mediterranean Deli.

On September 20, 1881, Arthur took the oath of office on the first floor of his home, following the death of James Garfield the previous evening.

In the history of the New York Courts, Arthur is known to us for his role in two prominent cases. He served as co-counsel in the Lemmon Slave Case, waged during the 1850s, and in representing Elizabeth Jennings, an African-American woman who on July 16, 1854, like Rosa Parks a century later, was denied a seat on public transportation. Arthur prevailed, and the railway paid a damages verdict and changed its policy.

Images:

Chester A. Arthur sworn in as President of the United States in his home, 1881. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-7615

Photograph of Chester A. Arthur’s home, 1914. Published in The Presidents of the United States, 1789-1914, ed. James Grant Wilson

Modern-day photograph of Chester Arthur’s home, featuring Kalustyan’s, 2007. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

October 2019

John Jay Homestead Historic Site, Katonah

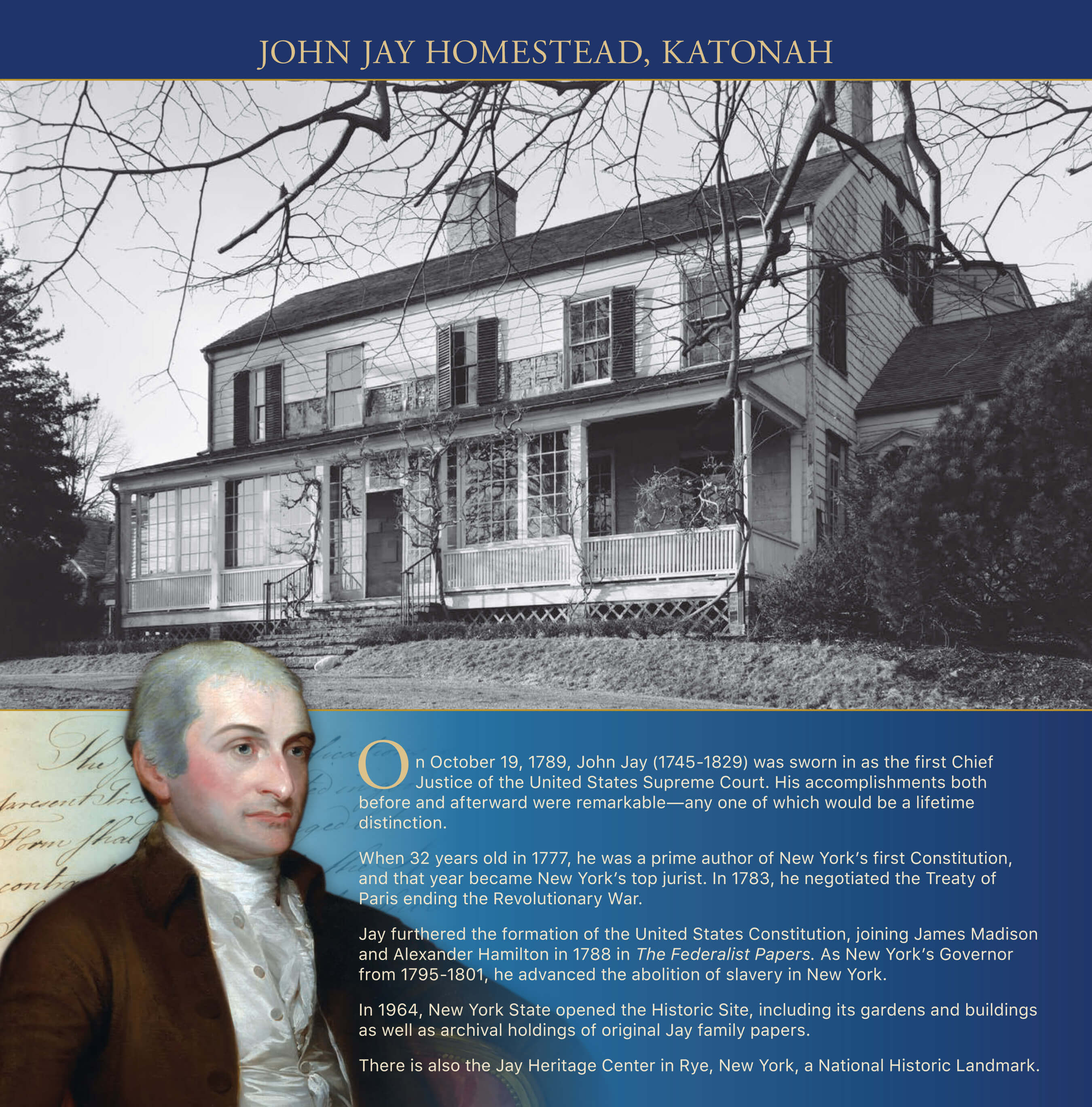

On October 19, 1789, John Jay (1745-1829) was sworn in as the first Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. His accomplishments both before and afterward were remarkable—any one of which would be a lifetime distinction.

When 32 years old in 1777, he was a prime author of New York’s first Constitution, and that year became New York’s top jurist. In 1783, he negotiated the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War.

Jay furthered the formation of the United States Constitution, joining James Madison and Alexander Hamilton in 1788 in The Federalist Papers. As New York’s Governor from 1795-1801, he advanced the abolition of slavery in New York.

In 1964, New York State opened the Historic Site, including its gardens and buildings as well as archival holdings of original Jay family papers.

There is also the Jay Heritage Center in Rye, New York, a National Historic Landmark.

Images:

Portrait of John Jay, painted by John Trumbull, begun 1784, completed by 1818, oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, NPG.74.46

Photograph of the John Jay Homestead. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, Survey Number: HABS NY-4393

The final page of the Treaty of Paris, which Jay, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin signed, 1783. National Archives and Records Administration, Identifier 299805

November 2019

Rosemount, Esopus

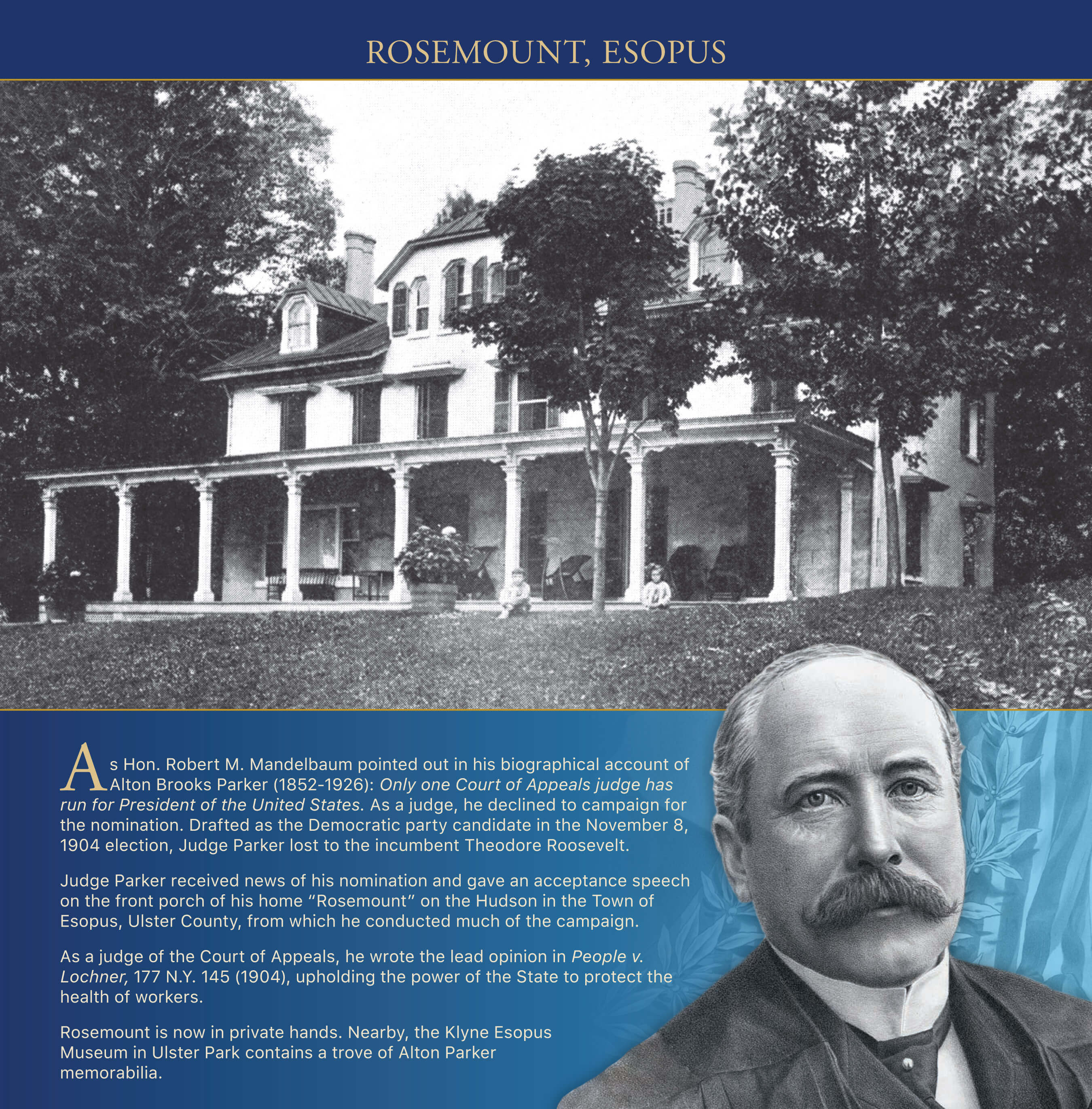

As Hon. Robert M. Mandelbaum pointed out in his biographical account of Alton Brooks Parker (1852-1926): Only one Court of Appeals judge has run for President of the United States. As a judge, he declined to campaign for the nomination. Drafted as the Democratic party candidate in the November 8, 1904 election, Judge Parker lost to the incumbent Theodore Roosevelt.

Judge Parker received news of his nomination and gave an acceptance speech on the front porch of his home “Rosemount” on the Hudson in the Town of Esopus, Ulster County, from which he conducted much of the campaign.

As a judge of the Court of Appeals, he wrote the lead opinion in People v. Lochner, 177 N.Y. 145 (1904), upholding the power of the State to protect the health of workers.

Rosemount is now in private hands. Nearby, the Klyne Esopus Museum in Ulster Park contains a trove of Alton Parker memorabilia.

Images:

Print from Parker’s presidential campaign, running as the Democratic candidate, 1904. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-07827

Postcard of Parker’s home in Esopus, Rosemount. Credit: Vivian Yess Wadlin, courtesy of The Hudson River Valley Institute

Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, 1904. Courtesy of HathiTrust

December 2019

Samuel Seabury Playground, New York City

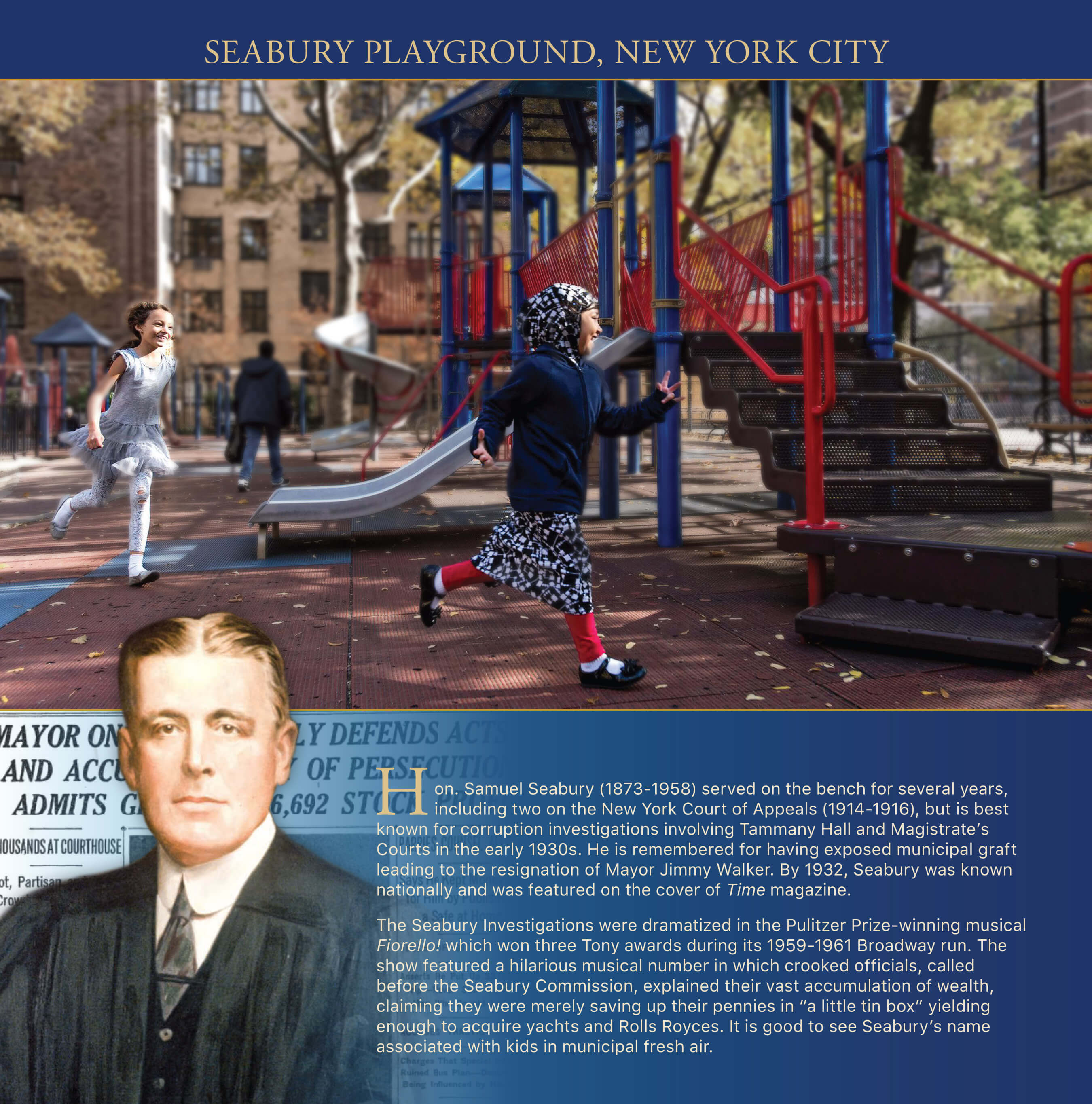

Hon. Samuel Seabury served on the bench for several years, including two on the New York Court of Appeals (1914-1916), but is best known for corruption investigations involving Tammany Hall and Magistrate’s Courts in the early 1930s. He is remembered for having exposed municipal graft leading to the resignation of Mayor Jimmy Walker. By 1932, Seabury was known nationally and was featured on the cover of Time magazine.

The Seabury Investigations were dramatized in the Pulitzer Prize-winning musical Fiorello! which won three Tony awards during its 1959-1961 Broadway run. The show featured a hilarious musical number in which crooked officials, called before the Seabury Commission, explained their vast accumulation of wealth, claiming they were merely saving up their pennies in “a little tin box” yielding enough to acquire yachts and Rolls Royces. It is good to see Seabury’s name associated with kids in municipal fresh air.

Images:

Portrait of Hon. Samuel Seabury from the College of the of the NYS Court of Appeals. Courtesy of the Historical Society of the New York Courts

The New York Times, May 26, 1932. Copyright The New York Times

Children play at the Samuel Seabury Playground, 2016, photographed by Mark Kauzlarich for the New York Times. The New York Times, November 13, 2016. Copyright Mark Kauzlarich/The New York Times