Description

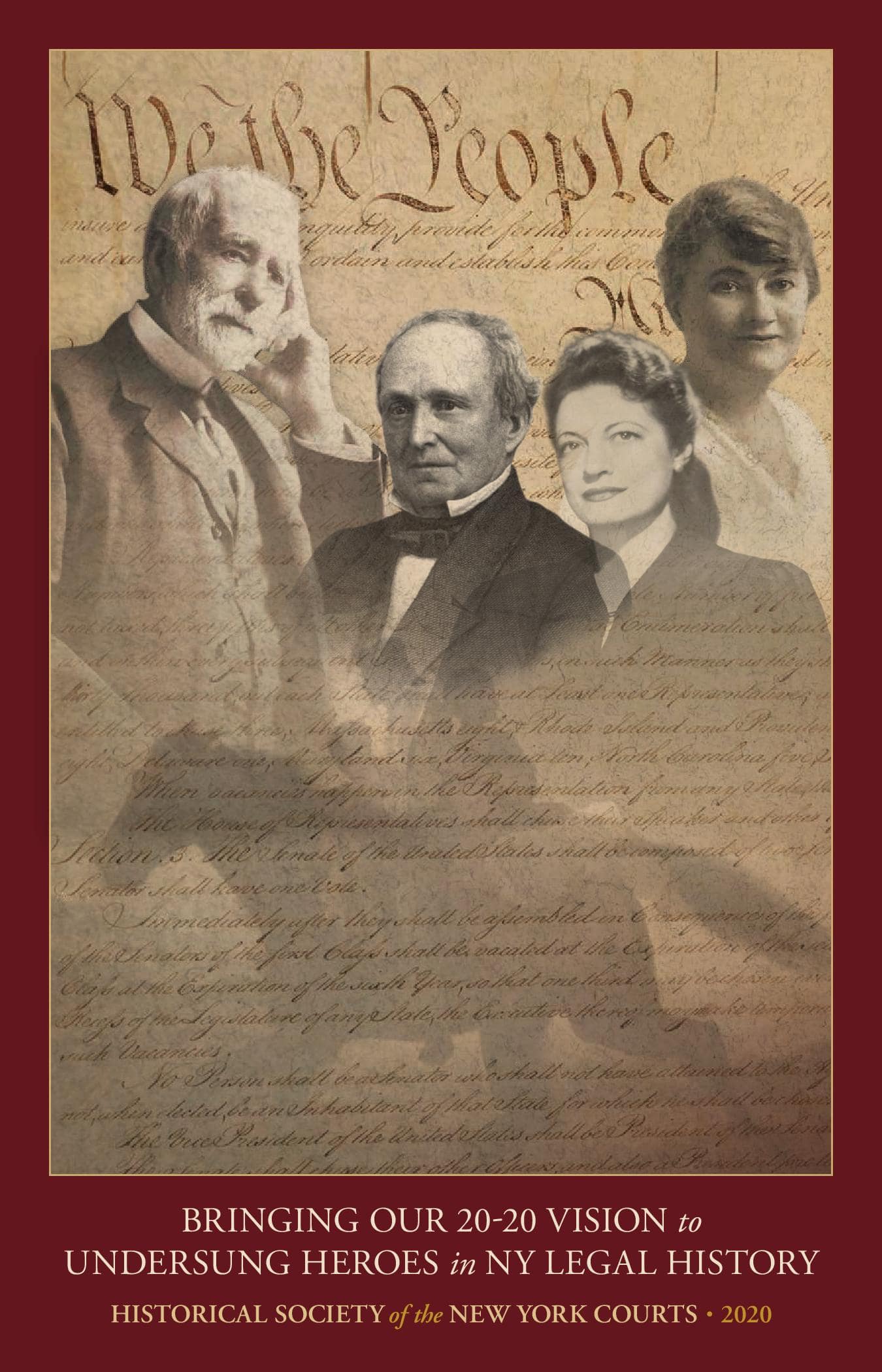

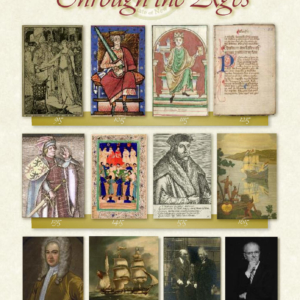

Mary Madden Lilly (1859-1930)

The first woman attorney elected to the New York Legislature: Lawyer, School Teacher, Wife, Mother, Editor, Legislator, Reformer, Penologist

In November 1918, the voters in the Seventh Assembly District in Manhattan voted in Mary Madden Lilly as a member of the Assembly.[1] She was an attorney, a Democrat (the minority party in the Assembly at that time), and the first woman attorney to serve in New York’s legislature. She earned her law degree in 1895 from NYU School of Law at age 35 as its first woman graduate.

Ms. Lilly graduated from Hunter College in 1876 and taught elementary school before going to law school on a full scholarship she won on a competitive exam, reportedly the first such grant ever received by a woman. In 1915, she was among six members of the Women’s Lawyers Association who volunteered to serve as counsel to the female defendants brought into Women’s Night Court.

As a legislator she advanced causes in prison reform, women’s suffrage, death penalty abolition for minors, and aid to mental defectives. She was also Superintendent of the female workhouse on Blackwell’s Island (Welfare Island), where she undertook reforms in treatment and detention.[2]

[1] On the same date in November, 1918, Long Island voters elected Ida Sammis from Huntington to the New York State Assembly.

[2] See Thomas C. McCarthy, Foursome of Ticket Firsts: Sarah Palin, Geraldine Ferraro…. Katherine Bement Davis? Mary M. Lilly? Chapter V, New York Correction History Society (2008), available at http://www.correctionhistory.org/html/chronicl/4ticketfirsts/4ticketfirstschapterfive.html; Women Attorney Trailblazers in New York State, New York State Bar Association Committee on Women in the Law (undated); Mrs. Mary F. Lilly, Noted Lawyer, Dies, The New York Times, October 12, 1930, at 63.

Images:

Mary M. Lilly’s campaign poster for the NYS Assembly. With thanks to her great granddaughter Constance Gerard

The New York Times, August 2, 1918. Copyright The New York Times

Completed design of the NYS Capitol, Albany, by James R. Osgood & Co., c. 1884. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

February 2020

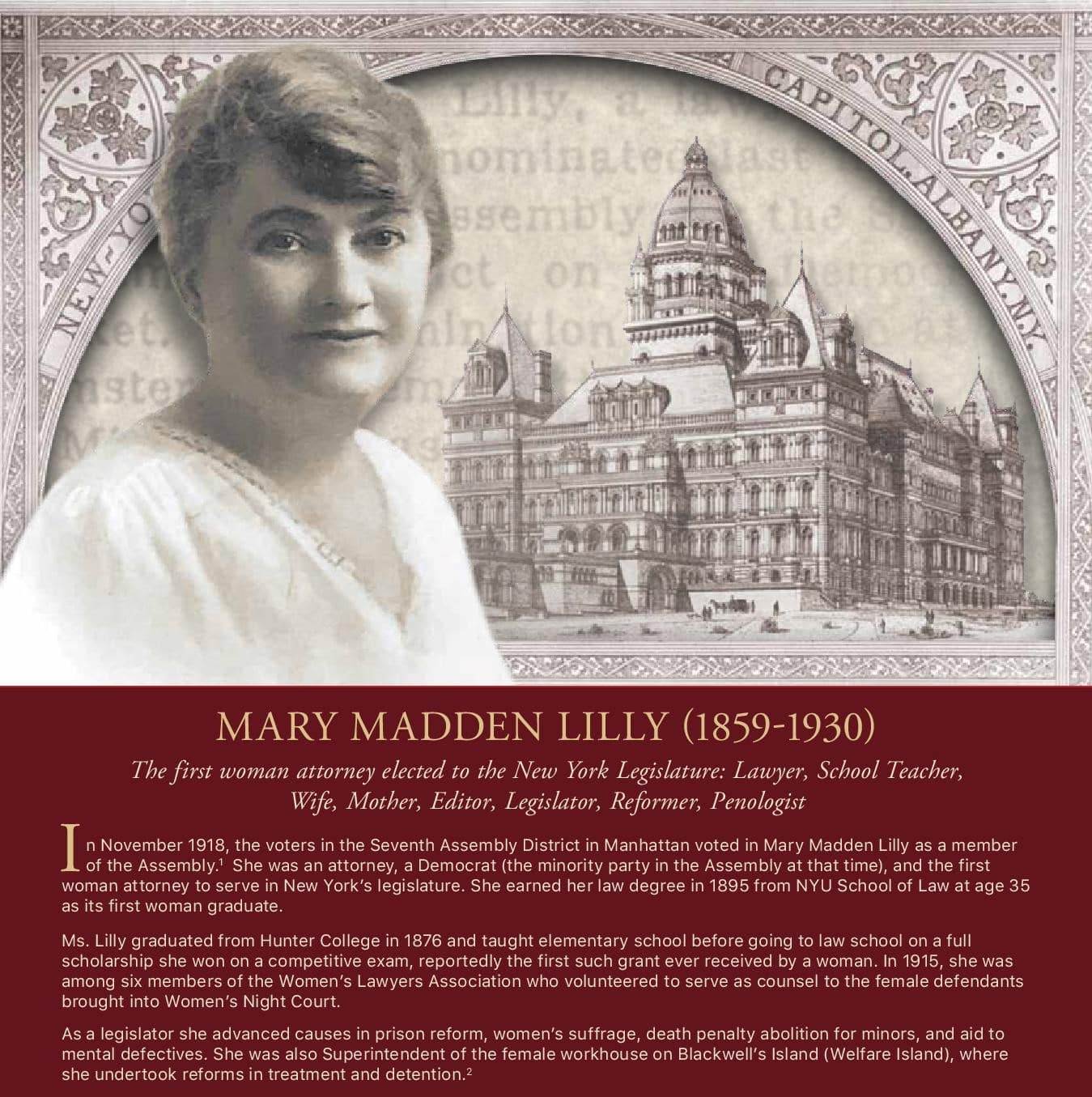

Gouverneur Morris (1752-1816)

James Madison stands in the first rank of our Founders for having been the primary author of the U.S. Constitution. But the Founders, thoughtfully, created a Committee of Style, which took their concepts and delivered them in the most elegant phrasing. Gouverneur Morris is known for his role on the committee, which revised Madison’s original opening and gave us the more enduring:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity…

Morris was among the few delegates who delivered passionate orations denouncing slavery, stating that a slave trader in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity tears away his fellow creatures from their dearest connections & damns them to the most cruel bondages.

A gifted scholar, Morris enrolled in 1764, at age 12, at King’s College, now Columbia. He was in his mid-twenties when he drafted the first Constitution of New York State in 1777 along with John Jay and Robert R. Livingston.[1]

[1] See Brookhiser, Richard, Gentleman Revolutionary: Gouverneur Morris, the Rake Who Wrote the Constitution (2003); The man who wrote the Preamble of the Constitution, National Constitution Center Constitution Daily (2019), https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-man-who-wrote-the-preamble-of-the-constitution; Hilary Parkinson, Constitution 225: It takes a committee to write a Preamble, U.S. National Archives Pieces of History (September 11, 2012), https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2012/09/11/constitution-225-it-takes-a-committee-to-write-a-preamble; Madison Debates, August 8, Yale Law School The Avalon Project (2008), https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_808.asp.

Images:

Portrait of Gouverneur Morris painted by James Sharples, 1810, pastel on paper. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Miss Ethel Turnbull in memory of her brothers, John Turnbull and Gouverneur Morris Wilkins Turnbull

Constitution of the United States, 1787. National Archives and Records Administration, 1667751

Engraving of Gouverneur Morris’s family estate, Morrisania, c. 1880. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library

March 2020

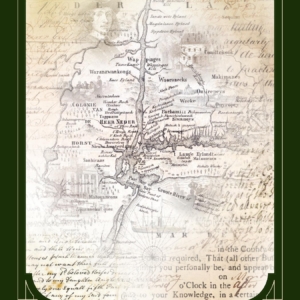

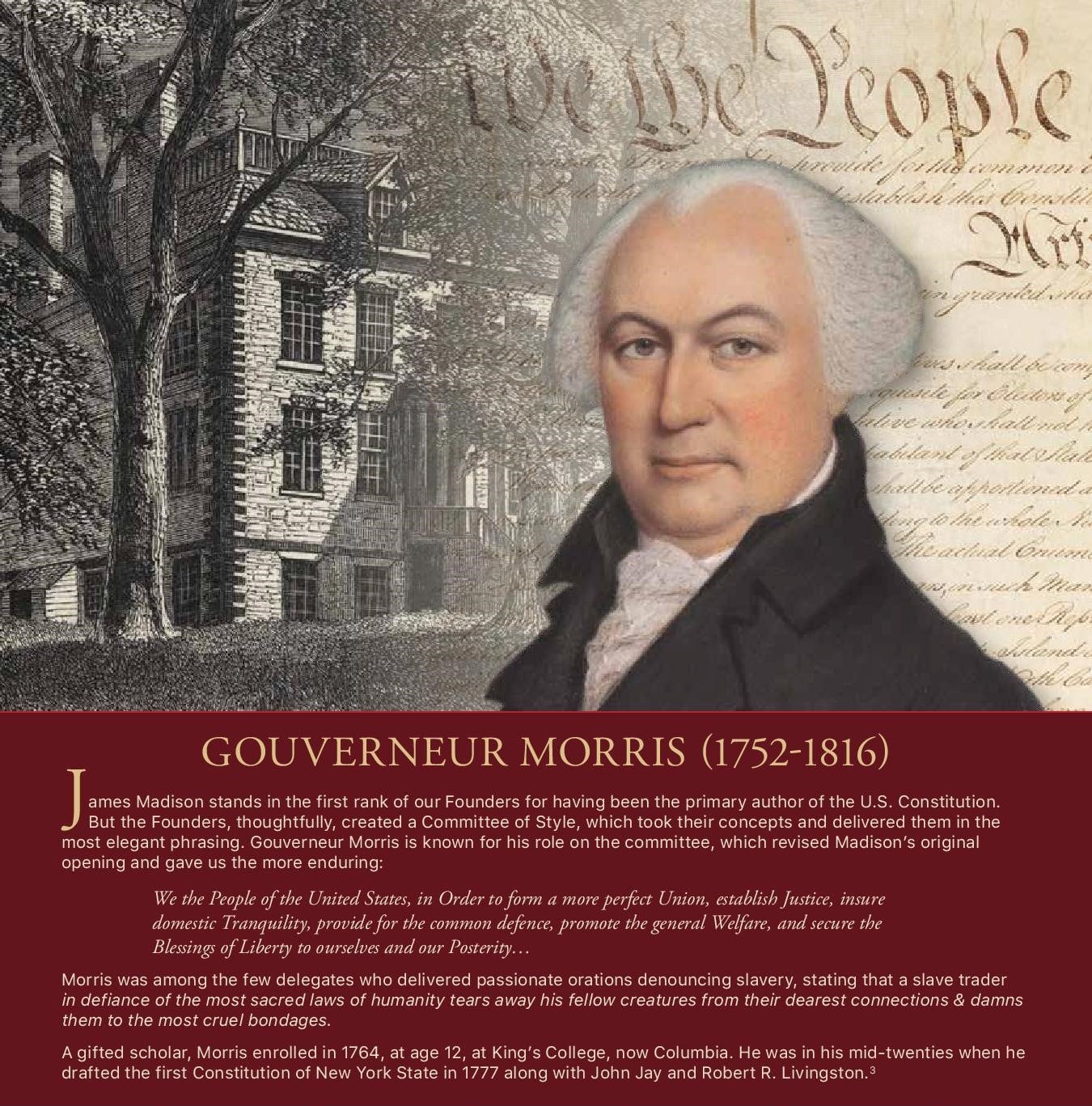

Adriaen van der Donck (1620-1655)

Adriaen van der Donck was the first of the early immigrants who had a university and a legal education, having entered the University of Leiden in 1638, graduating with a law degree in 1641. Fascinated by prospects in the New World, he became schout (a title that took in several law enforcement functions) for the region then called Rensselaerswijck, today the area around the capital region, and then went to New Amsterdam, around today’s Manhattan, where he became increasingly politically active. In Russell Shorto’s The Island at the Center of the World, van der Donck emerges as a central figure who, in seeking a more democratic system, challenged Pieter Stuyvesant’s autocratic rule.

As an appendix to his petition for more liberal governance, he gave the Netherlands States General one of the earliest and most comprehensive descriptions of America at the time, Beschryvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant (Description of New Netherland), which attracted settlers to our shores.

In time, he was addressed by the honorary title jonkheer, which morphed into the name Yonkers.

He was an advocate for Native American rights. Ironically, he was (thought to have been) killed, while only in his mid-thirties, in an attack by Native Americans. The standard painting of him is of uncertain provenance.[1]

[1] See van den Hout, J., Adriaen van der Donck: A Dutch Rebel in Seventeenth-Century America (2018); Adriaen van der Donck [1620-1655]: Early Founder/Historic Leader, New Netherland Institute, https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/history-and-heritage/dutch_americans/adriaen-van-der-donck/ (last visited June 18, 2019); Jaap Jacobs, A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth Century America (2005); Russell Shorto, The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America (2004).

Images:

Portrait of a Man, often thought to be Adrian van der Donck, mid-17th century, oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection

Title page of Adriaen van der Donck’s Beschryvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant (Description of New Netherland), first published in 1655. Courtesy of Google Books

Novi Belgii Novaeque Angliae, a map produced by Nicolaes Visccher and commissioned by Adriaen van der Donck, reprinted in 1685. Library of Congress, Geography & Map Division, G3715 169- .V5

April 2020

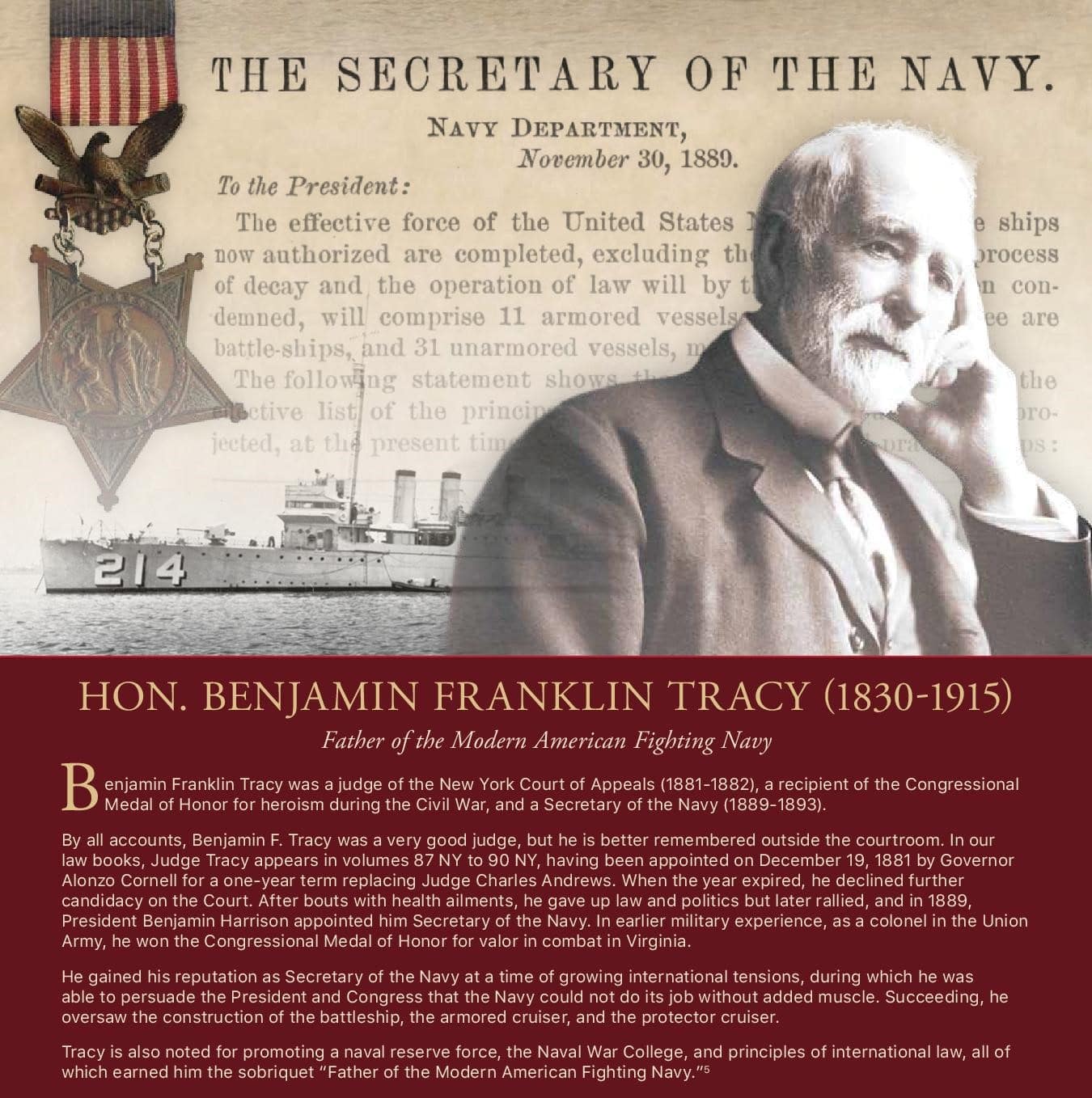

Hon. Benjamin Franklin Tracy (1830-1915)

Father of the Modern American Fighting Navy

Benjamin Franklin Tracy was a judge of the New York Court of Appeals (1881-1882), a recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor for heroism during the Civil War, and a Secretary of the Navy (1889-1893).

By all accounts, Benjamin F. Tracy was a very good judge, but he is better remembered outside the courtroom. In our law books, Judge Tracy appears in volumes 87 NY to 90 NY, having been appointed in December 19, 1881 by Governor Alonzo Cornell for a one-year term replacing Judge Charles Andrews. When the year expired, he declined further candidacy on the Court. After bouts with health ailments, he gave up law and politics but later rallied, and in 1889, President Benjamin Harrison appointed him Secretary of the Navy. In earlier military experience, as a colonel in the Union Army, he won the Congressional Medal of Honor for valor in combat in Virginia.

He gained his reputation as Secretary of the Navy at a time of growing international tensions, during which he was able to persuade the President and Congress that the Navy could not do its job without added muscle. Succeeding, he oversaw the construction of the battleship, the armored cruiser, and the protector cruiser.

Tracy is also noted for promoting a naval reserve force, the Naval War College, and principles of international law, all of which earned him the sobriquet “Father of the Modern American Fighting Navy.”[1]

[1] See Dautel, Susan S., Benjamin Franklin Tracy, in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Albert M. Rosenblatt (2007), 215-225; B. Franklin Cooling, Benjamin Franklin Tracy: Father of the Modern American Fighting Navy (1973).

Images:

Portrait of Hon. Benjamin Franklin Tracy, c. 1915. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-B2- 2676-13

Photograph of the USS Tracy, named for Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Franklin Tracy NH 60241. Courtesy of the Naval History & Heritage Command

Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1889. Courtesy of HathiTrust

May 2020

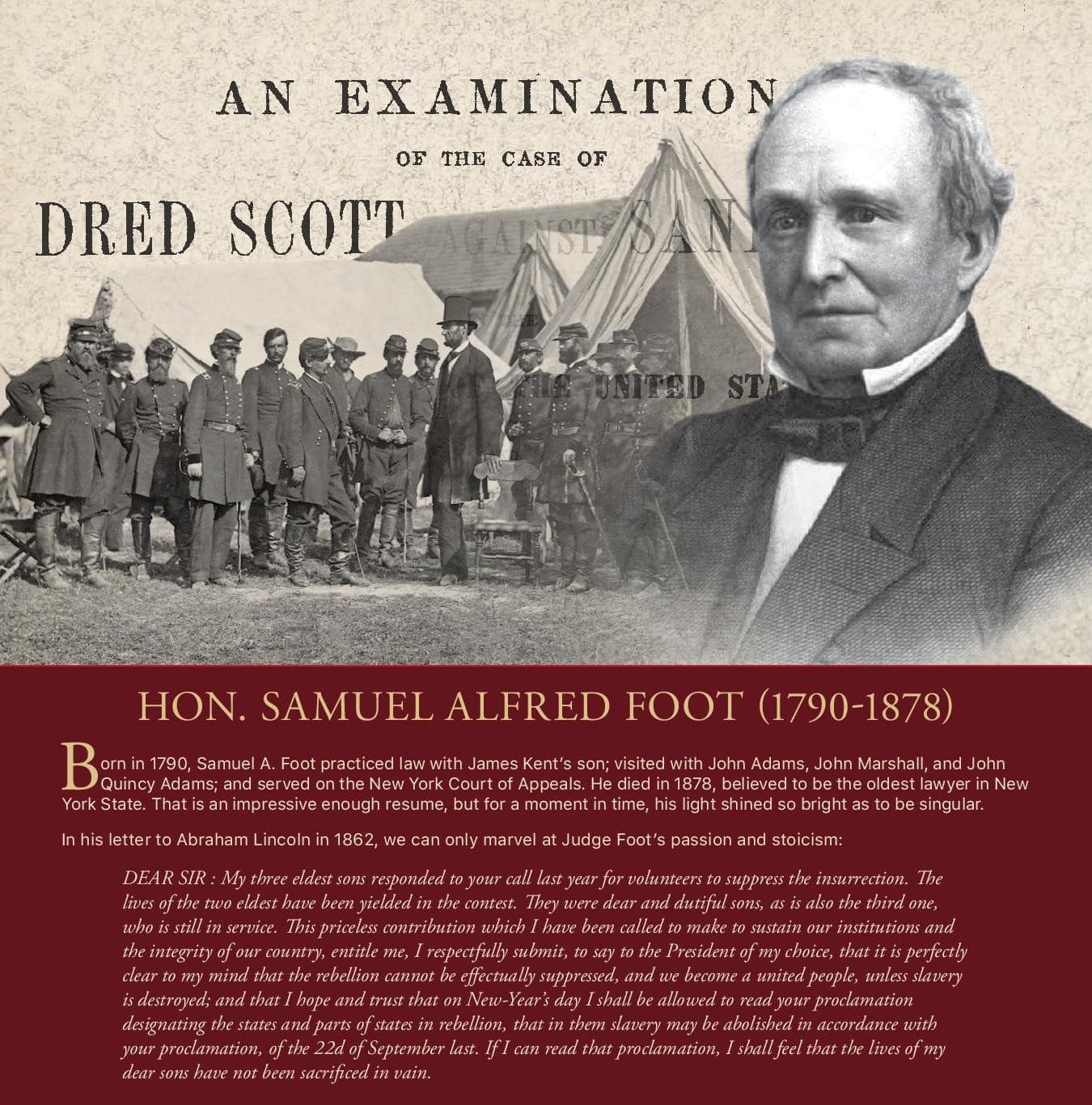

Hon. Samuel Alfred Foot (1790-1878)

Born in 1790, Samuel A. Foot practiced law with James Kent’s son; visited with John Adams, John Marshall, and John Quincy Adams; and served on the New York Court of Appeals. He died in 1878, believed to be the oldest lawyer in New York State. That is an impressive enough resume, but for a moment in time, his light shined so bright as to be singular.

In his letter to Abraham Lincoln in 1862, we can only marvel at Judge Foot’s passion and stoicism:

DEAR SIR : My three eldest sons responded to your call last year for volunteers to suppress the insurrection. The lives of the two eldest have been yielded in the contest. They were dear and dutiful sons, as is also the third one, who is still in service. This priceless contribution which I have been called to make to sustain our institutions and the integrity of our country, entitle me, I respectfully submit, to say to the President of my choice, that it is perfectly clear to my mind that the rebellion cannot be effectually suppressed, and we become a united people, unless slavery is destroyed; and that I hope and trust that on New-Year’s day I shall be allowed to read your proclamation designating the states and parts of states in rebellion, that in them slavery may be abolished in accordance with your proclamation, of the 22d of September last. If I can read that proclamation, I shall feel that the lives of my dear sons have not been sacrificed in vain.

Images:

Portrait of Hon. Samuel A. Foot. Published in Autobiography: Collateral Reminiscences, Arguments in Important Causes, Speeches, Address, Lectures, and Other Writings by Samuel A. Foot, 1873

President Abraham Lincoln visits Antietam with General George McClellan and a group of officers, 1862. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-B817- 7951

Cover page of An Examination of the Case of Dred Scott Against Sandford, a talk delivered by Hon. Samuel A. Foot, 1859. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections, E450 .F68 1859

June 2020

Albert Gallatin (1761-1849)

Albert Gallatin was born in Geneva in 1761. He died in Astoria, Queens in 1849 and was buried in Trinity Churchyard in Manhattan, but not before serving as a delegate to a Pennsylvania state convention to discuss possible revisions to the U.S. Constitution in 1788. He is best known for serving as Secretary of the Treasury from 1801 to 1814 under Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

A champion of Enlightenment philosophy, Gallatin served in the Revolutionary War, taught French at Harvard, and served as a U.S. Senator and member of the House of Representatives.

Gallatin is known for his diplomacy in negotiations for the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, ending the War of 1812 between the U.S. and Great Britain.

In 1831, Gallatin would help found a small, non-denominational college near City Hall in Manhattan called the University of the City of New York. It would become New York University, at which Gallatin was celebrated on Founder’s Day in 2015. In 2018, the Gallatin Law Society was formed to create a lively forum where NYU students can talk about law.

Images:

Albert Gallatin, painted by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1803. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Frederic W. Stevens, 1908

Albert Gallatin’s list of information for his commission in the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812, 1815. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, The James Madison Papers at the Library of Congress

University of the City of New York, founded by Albert Gallatin, 1850. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library

July 2020

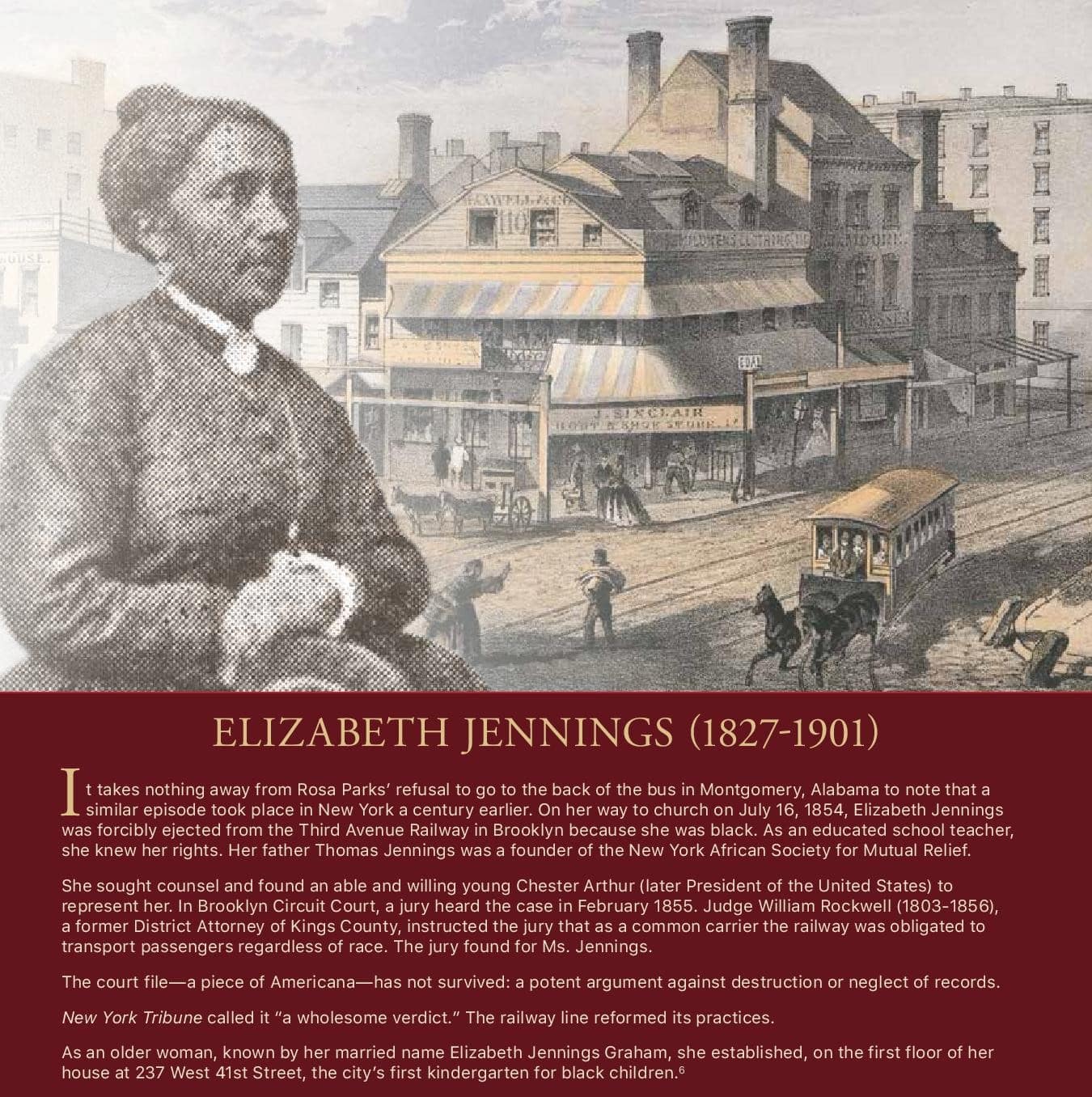

Elizabeth Jennings (1827-1901)

It takes nothing away from Rosa Parks refusal to go to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama to note that a similar episode took place in New York a century earlier. On her way to church on July 16, 1854, Elizabeth Jennings was forcibly ejected from the Third Avenue Railway in Brooklyn because she was black. As an educated school teacher, she knew her rights. Her father Thomas Jennings was a founder of the New York African Society for Mutual Relief.

She sought counsel and found an able and willing young Chester Arthur (later President of the United States) to represent her. In Brooklyn Circuit Court, a jury heard the case in February 1855. Judge William Rockwell (1803-1856), a former District Attorney of Kings County, instructed the jury that as a common carrier the railway was obligated to transport passengers regardless of race. The jury found for Ms. Jennings.

The court file—a piece of Americana—has not survived: a potent argument against destruction or neglect of records.

New York Tribune called it “a wholesome verdict.” The railway line reformed its practices.

As an older woman, known by her married name Elizabeth Jennings Graham, she established, on the first floor of her house at 237 West 41st Street, the city’s first kindergarten for black children.[1]

[1] See National Anti-Slavery Standard, March 3, 1885; Frederick Douglass’ Paper, September 22, 1854; New York Age, July 26, 1930; New-York Tribune, July 19, 1854; New York Tribune, February 23, 1855; Jerry Mikorenda, America’s First Freedom Fighter: Elizabeth Jennings, Chester Arthur, and the Early Fight for Civil Rights (2020).

Images:

Portrait of Elizabeth Jennings, c. 1855. Courtesy of kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply

Corner of Pearl & Chatham Street, near where Elizabeth Jennings hailed the streetcar, 1861. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library

Metropolitan Street Railway Horsecar Car Number 97, which would have been similar to the one hailed by Elizabeth Jennings, 1917. Courtesy of New York Transit Museum

August 2020

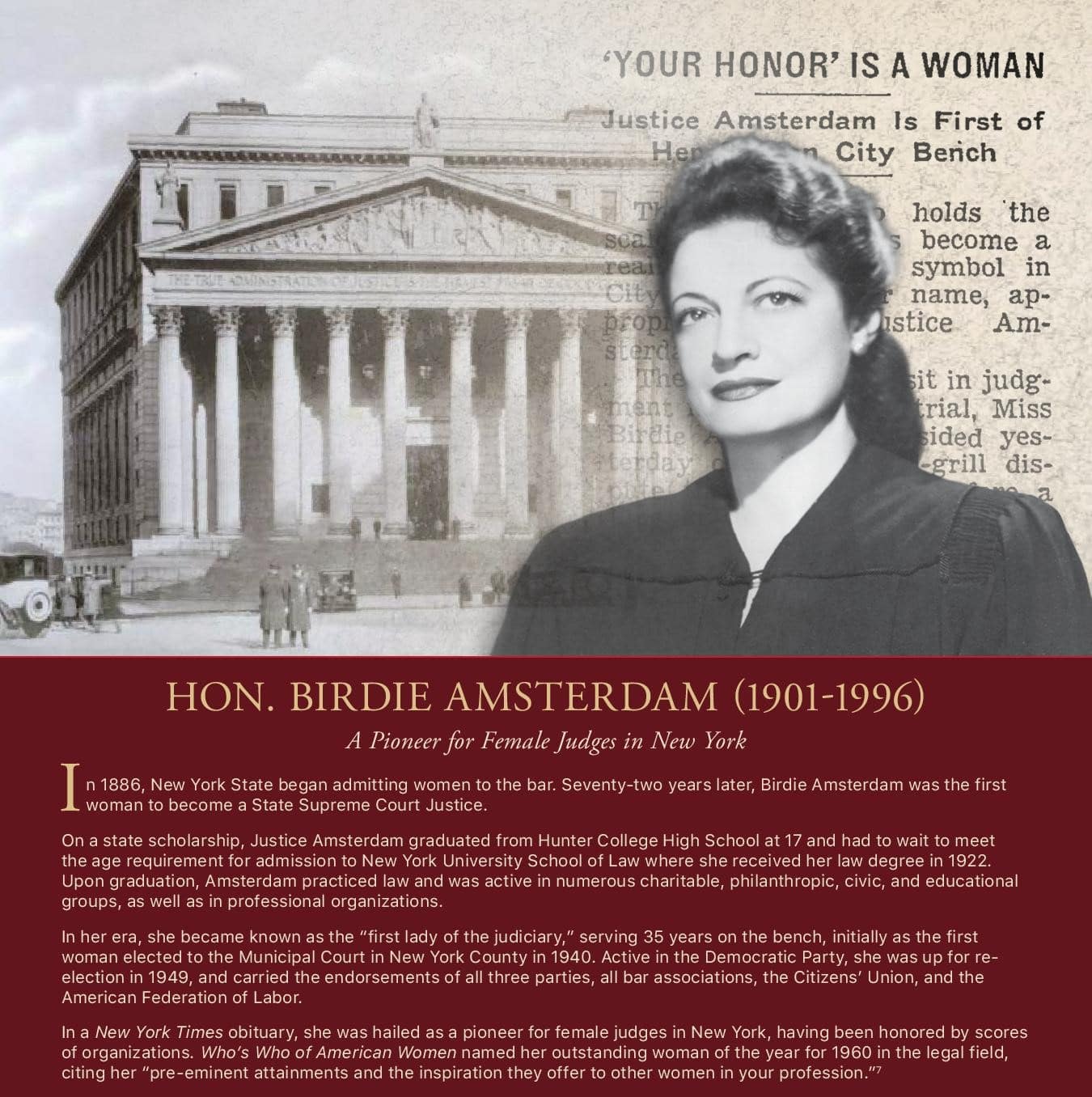

Hon. Birdie Amsterdam (1901-1996)

A Pioneer for Female Judges in New York

In 1886, New York State began admitting women to the bar. Seventy-two years later, Birdie Amsterdam was the first woman to become a State Supreme Court Justice.

On a state scholarship, Justice Amsterdam graduated from Hunter College High School at 17 and had to wait to meet the age requirement for admission to New York University School of Law where she received her law degree in 1922. Upon graduation, Amsterdam practiced law and was active in numerous charitable, philanthropic, civic, and educational groups, as well as in professional organizations.

In her era, she became known as the “first lady of the judiciary,” serving 35 years on the bench, initially as the first woman elected to the Municipal Court in New York County in 1940. Active in the Democratic Party, she was up for re-election in 1949, and carried the endorsements of all three parties, all bar associations, the Citizens’ Union, and the American Federation of Labor.

In a New York Times obituary, she was hailed as a pioneer for female judges in New York, having been honored by scores of organizations. Who’s Who of American Women named her outstanding woman of the year for 1960 in the legal field, citing her “pre-eminent attainments and the inspiration they offer to other women in your profession.”[1]

[1] See Dorothy Thomas, Birdie Amsterdam, in Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia (2009) available at https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/amsterdam-birdie; Wolfgang Saxon, Birdie Amsterdam, 95, a Pioneer for Female Judges in New York, The New York Times, July 10, 1996; D. Thomas, Women Lawyers of the United States (1957).

Images:

Portrait of Hon. Birdie Amsterdam, c. 1957. From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York

New York County Courthouse, where Justice Amsterdam presided as a Supreme Court Justice. Collection of the Historical Society of the New York Courts

The New York Times, January 11, 1955. Copyright The New York Times

September 2020

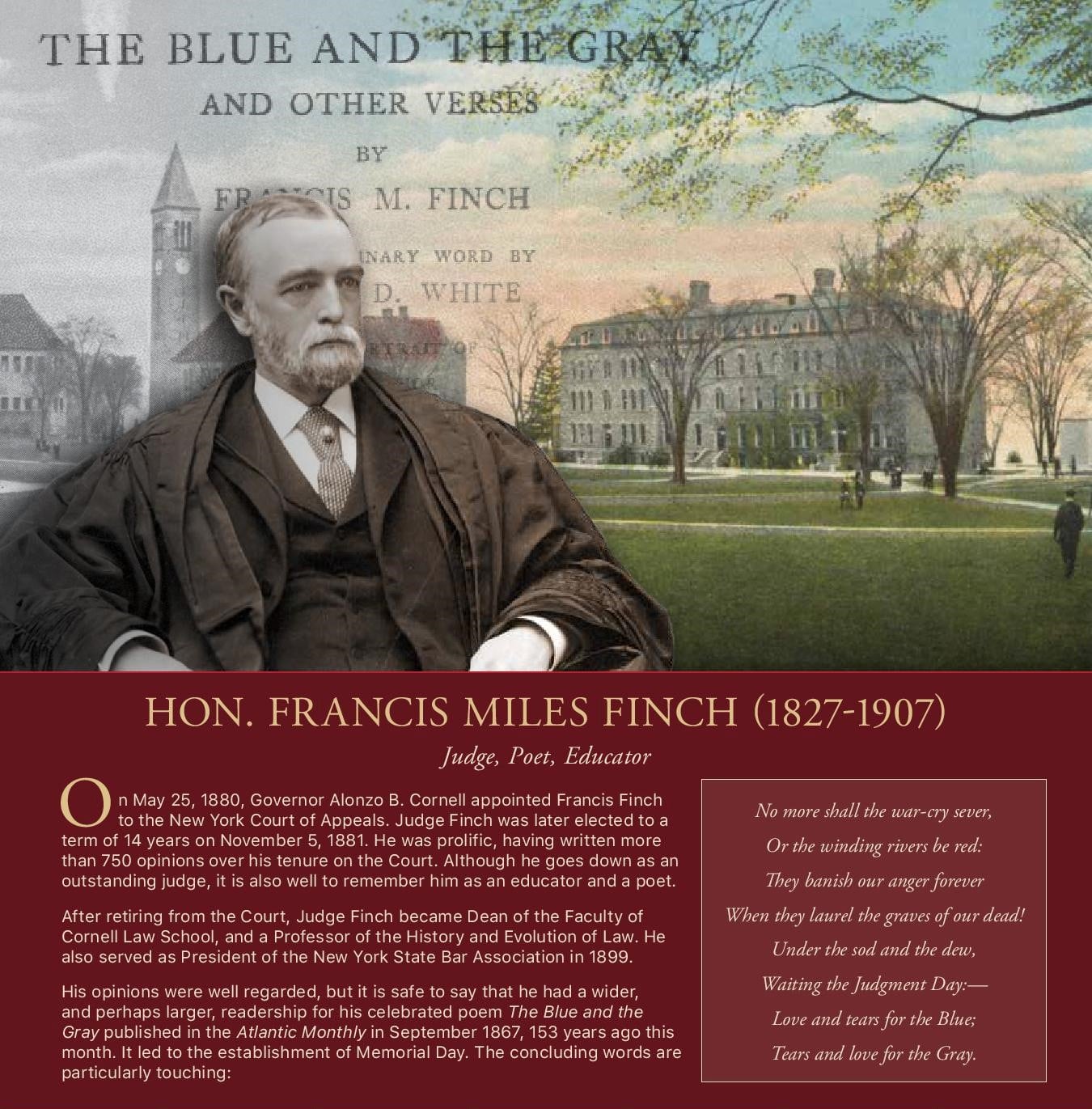

Hon. Francis Miles Finch (1827-1907)

Judge, Poet, Educator

On May 25, 1880, Governor Alonzo B. Cornell appointed Francis Finch to the New York Court of Appeals. Judge Finch was later elected to a term of 14 years on November 5, 1881. He was prolific, having written more than 750 opinions over his tenure on the Court. Although he goes down as an outstanding judge, it is also well to remember him as an educator and a poet.

After retiring from the Court, Judge Finch became Dean of the Faculty of Cornell Law School, and a Professor of the History and Evolution of Law. He also served as President of the New York State Bar Association in 1899.

His opinions were well regarded, but it is safe to say that he had a wider, and perhaps larger, readership for his celebrated poem The Blue and the Gray published in the Atlantic Monthly in September 1867, 153 years ago this month. It led to the establishment of Memorial Day. The concluding words are particularly touching:

No more shall the war-cry sever,

Or the winding rivers be red:

They banish our anger forever

When they laurel the graves of our dead!

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the Judgment Day:—

Love and tears for the Blue;

Tears and love for the Gray.

Images:

Portrait of Hon. Francis Finch. Division of Rare Book and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

Title page of The Blue and the Gray and Other Verses, written by Judge Finch. Published by Henry Holt and Company, 1909

South on the Quadrangle, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY; Morrill Hall was the original home of Cornell Law School, until it moved to Boardman Hall during Judge Finch’s tenure as Dean. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ds-02588

October 2020

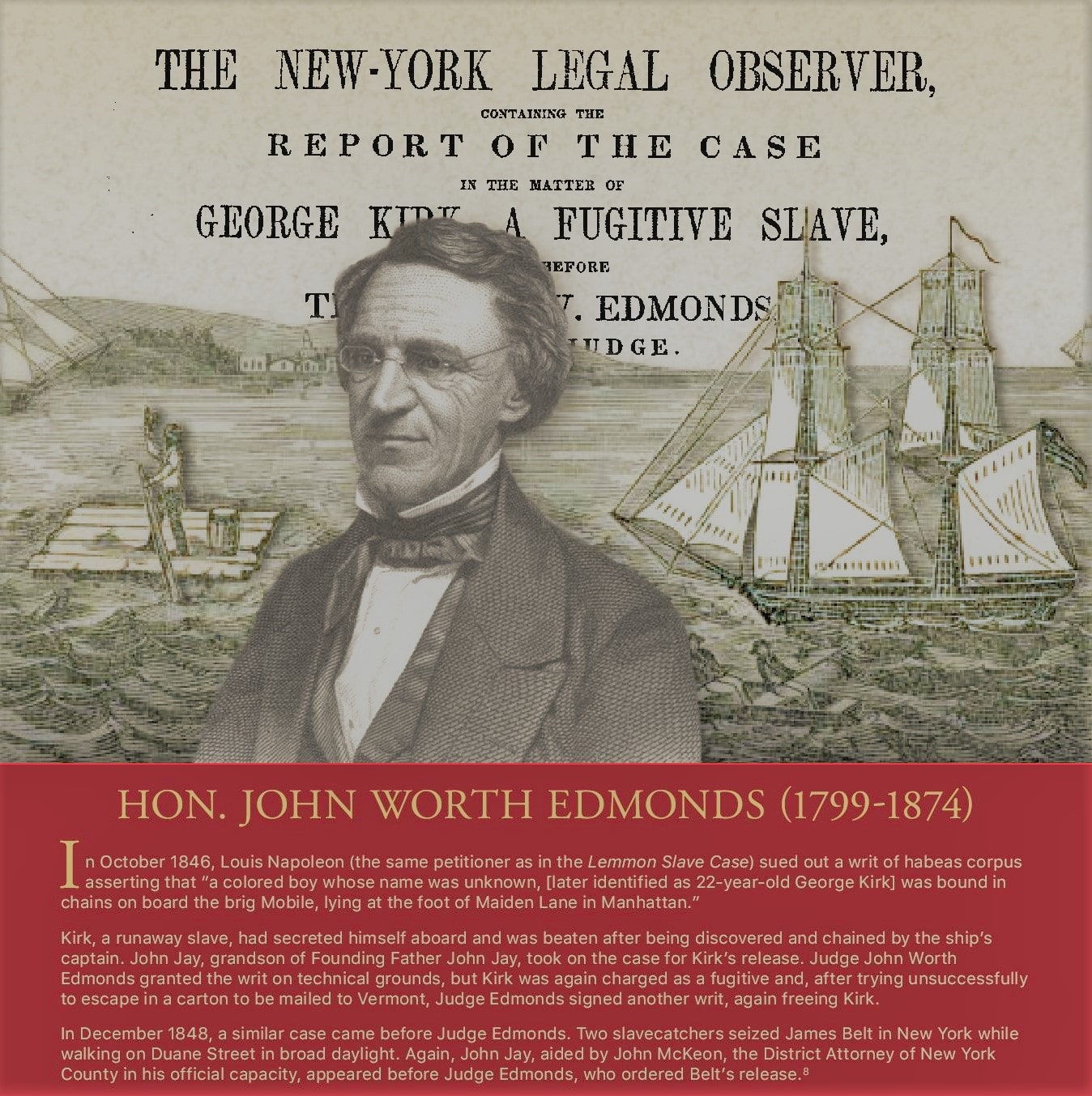

Hon. John Worth Edmonds (1799-1874)

In October 1846, Louis Napoleon (the same petitioner as in the Lemmon Slave Case) sued out a writ of habeas corpus asserting that “a colored boy whose name was unknown, [later identified as 22-year-old George Kirk] was bound in chains on board the brig Mobile, lying at the foot of Maiden Lane in Manhattan.”

Kirk, a runaway slave, had secreted himself aboard and was beaten after being discovered and chained by the ship’s captain. John Jay, grandson of Founding Father John Jay, took on the case for Kirk’s release. Judge John Worth Edmonds granted the writ on technical grounds, but Kirk was again charged as a fugitive and, after trying unsuccessfully to escape in a carton to be mailed to Vermont, Judge Edmonds signed another writ, again freeing Kirk.

In December 1848, a similar case came before Judge Edmonds. Two slavecatchers seized James Belt in New York while walking on Duane Street in broad daylight. Again, John Jay, aided by John McKeon, the District Attorney of New York County in his official capacity, appeared before Judge Edmonds, who ordered Belt’s release.[1]

[1] See Lemmon v. New York, 20 N.Y. 582 (1860); In the Matter of George Kirk, a fugitive slave, 4 N.Y. Leg. Obs. 456, 1 Parker Crim. Rep. 67, 1 Edm. Sel. Cas. 315, 9 Month. L. Rep. 355 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1846); In the Matter of Joseph Belt, an alleged fugitive from service, in the State of Maryland, 7 N.Y. Leg. Obs. 80, 1 Parker Crim. Rep. 169, 2 Edm. Sel. Cas. 93 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1848); The Slave Free, New-York Tribune, October 28, 1846, at 4; A Slave Case in the United States, The Guardian, December 26, 1846, at 5; The Slave Case, New-York Tribune, December 26, 1848, at 2; The Abduction Case, The Evening Post, December 27, 1848, at 2; Decision of the Slave Case by Judge Edmonds, The Evening Post, December 29, 1848, at 2.

Images:

Portrait of Hon. John Worth Edmonds. Published in The American Portrait Gallery by Lillian C. Buttre

Title page of Supplement to the New-York Legal Observer, Containing the Report of the Case in The Matter of George Kirk, a Fugitive Slave. Library of Congress, 98104378

View of fugitive slave Thomas M. Jones, escaping on a raft from the brig ship Bell offshore from New York City, 1871. General Research Division, The New York Public Library

November 2020

Eunice Hunton Carter (1899-1970)

Eunice Carter was the real-life heroine who inspired a character on the HBO series Boardwalk Empire. She was only the second woman in the history of Smith College to receive a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in four years. She then went on to earn a law degree from Fordham School of Law and start her own practice.

After the 1935 riots in Harlem, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia appointed her to the Commission on Conditions in Harlem. That same year, Special Prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey appointed her his assistant in one of the most prominent mobster prosecutions in American history. She was the only African-American and only woman on the 10-member staff and was instrumental in the successful prosecution of Lucky Luciano where she earned the title “Lady Racketbuster.” Carter served as Assistant District Attorney of New York County for 10 years. During that time, Dewey named her to lead the Abandonment Bureau of Women’s Courts.

She later entered private practice and connected her work with the National Council of Negro Women to international issues. In 1955, Carter was elected to chair the International Conference of Non-Governmental Organizations.

Above from Hackensack ( NJ) Record, January 27, 1970She died in New York City in 1970, at the age of 70. Her grandson Stephen L. Carter, a professor at Yale Law School, wrote Invisible: The Forgotten Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster, Henry Holt and Co. (2018).[1]

[1] See The Real-Life Heroine Who Inspired a Character on ‘Boardwalk Empire,’ The New York Times, December 7, 2018; Herb Boyd, Eunice Hunton Carter, a unique attorney and crime fighter, New York Amsterdam News (2018) available at http://amsterdamnews.com/news/2018/dec/13/eunice-hunton-carter-unique-attorney-and-crime-fig/; Cinque Henderson, Daughter of the black elite who brought down a gangster, The Washington Post, December 7, 2018.

Images:

Portrait of Eunice Carter, c. 1940. Courtesy of the Mob Museum

The Women’s Court, where Carter was a prosecutor, operated in the Jefferson Market Courthouse; her experiences at the Women’s Court brought much to prosecution of Luciano. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, Survey number: HABS NY-4392

The New York Times, June 8, 1936. Copyright The New York Times

December 2020

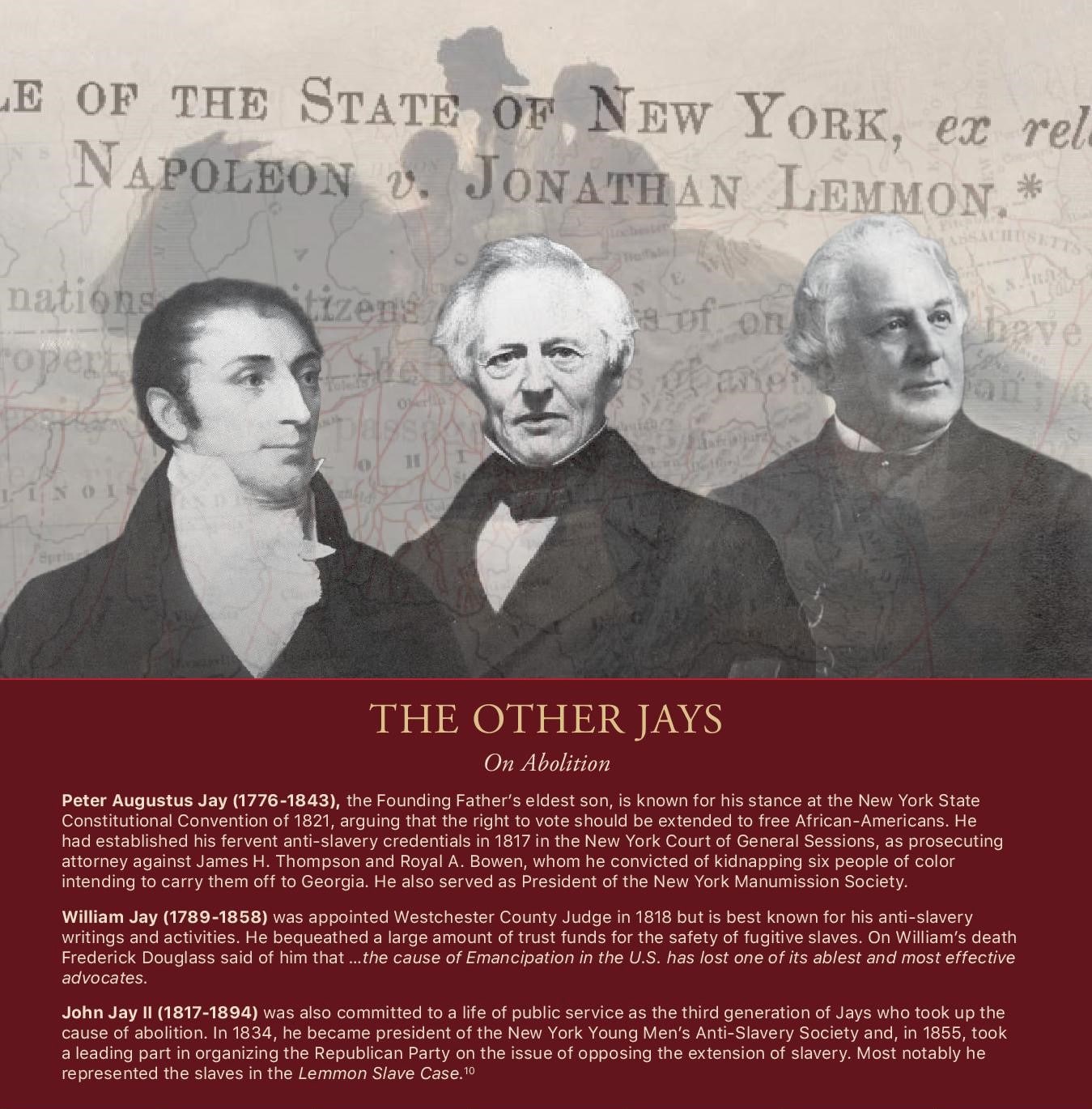

The Other Jays

On Abolition

Peter Augustus Jay (1776-1843), the Founding Father’s eldest son, is known for his stance at the New York State Constitutional Convention of 1821, arguing that the right to vote should be extended to free African Americans. He had established his fervent anti-slavery credentials in 1817 in the New York Court of General Sessions, as prosecuting attorney against James H. Thompson and Royal A. Bowen, whom he convicted of kidnapping six people of color intending to carry them off to Georgia. He also served as President of the New York Manumission Society.

William Jay (1789-1858) was appointed Westchester County Judge in 1818 but is best known for his anti-slavery writings and activities. He bequeathed a large amount of trust funds for the safety of fugitive slaves. On William’s death Frederick Douglass said of him that …the cause of Emancipation in the U.S. has lost one of its ablest and most effective advocates.

John Jay II (1817-1894) was also committed to a life of public service as the third generation of Jays who took up the cause of abolition. In 1834, he became president of the New York Young Men’s Anti-Slavery Society and, in 1855, took a leading part in organizing the Republican Party on the issue of opposing the extension of slavery. Most notably he represented the slaves in the Lemmon Slave Case.[1]

[1] See Jennifer P. McLean, The Jays of Bedford (1884); Daniel Rogers, James H. Thompson and Royal A. Bowen’s Cases, in New-York City-Hall Recorder 2, 120 (1817).

Images:

Portrait of John Jay II. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society Photo Archives, Portraits of American Abolitionists, Photo. Coll. 81

Portrait of William Jay by Anthon Henry Wenzler. Published in William Jay and the Constitutional Movement for the Abolition of Slavery by Bayard Tuckerman

Portrait of Peter Augustus Jay. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, via Minard38 CC BY-SA 4.0

The Superior Court’s decision in The People of the State of New York, ex rel. Louis Napoleon v. Jonathan Lemmon. Courtesy of the NYS Court of Appeals Library