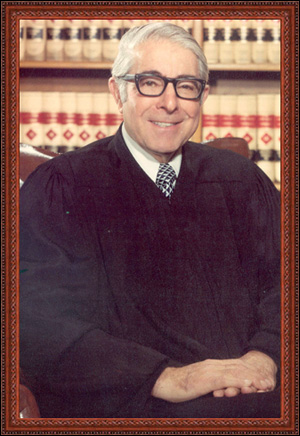

For Judge Samuel Rabin, the law was always about people.

Sam Rabin was born in New York City on October 12, 1905, and attended public high school in Brooklyn and Queens. He went on to Cornell University (class of 1926), where he was a cross-country track star, known as “Rabbit” Rabinowitch. In 1928, he took his law degree at NYU Law School. While still in college, and to help pay for his law school tuition, he sold racoon coats for his father, a furrier.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Sam Rabin had a small general practice in Jamaica, Queens, where he dealt with the everyday problems faced by ordinary citizens, and was very active in the local Bar Association. In a profile in the New York Post1, Judge Rabin called himself “a country lawyer, and a Madison Avenue lawyer part of the time.” The latter reference was to his earlier association with Armin Mittlemann, a Madison Avenue entertainment lawyer who later became his father-in-law. In one of his early assignments, which Rabin accepted reluctantly, he had to represent the boss’s daughter in a matter growing out of an automobile accident. He resented the long hours spent escorting Florence to court, but several years later the annoyance blossomed into romance, and the couple was married on February 11, 1938.

In 1942, looking for a rising star to challenge the incumbent Democratic assemblyman, the Republican party chose Sam Rabin. Though Rabin lost, he ran a spirited campaign, which earned him another shot the following election cycle. With gas rationing still on during the war, Rabin campaigned by public bus. In a profile in the Long Island Daily Press, he was quoted as saying that others had to lay up their cars because of the gas shortage, “so why shouldn’t I?”2 Judge Rabin was elected assemblyman from Queens for five terms. His winning election slogan was “A vote for Rabin is a vote for Queens.” The family fondly recalls their yearly trips to Albany, boarding the then-elegant Empire State Express early in the morning at Grand Central Station, and watching the legislators carry out their business in the club car.

A highlight of the family’s annual visit to Albany was their audience with the Governor, Thomas Dewey. In honor of the Governor, a fellow Republican, whose popularity helped carry the rest of the ticket, the Rabin family named their fox terrier Dewey. The children were instructed not to give away the dog’s real name, for fear embarrassing the Governor. In public, the dog was always referred to as “Rover,” and that pseudonym appears in the caption of an election campaign photo in the local newspaper.

Assemblyman Rabin’s legislative accomplishments included a bill that mandated liability insurance for all automobile drivers, and bills on housing and rent control,3 education, reapportionment, and the regulation of adoption of babies.4 He chaired the assembly committee on insurance. Assemblyman Rabin was popular in his community. His children recall that it was impossible to go out to dinner without countless constituents coming to the table while the food got cold, and that dozens of people would stop the Assemblyman in his tracks and greet him warmly as he walked along Jamaica Avenue, where his law office was located.

In 1950, Rabin successfully ran for a Supreme Court judgeship. He spent close to 10 years as a trial court judge sitting in Jamaica. He was a highly energetic judge, who tried to keep his docket moving. He pressed lawyers to reach settlements, and grew impatient with lawyers who slowed things down. In those days, the Justices whose chambers were in Queens were required to “ride circuit” to far away Riverhead once a year. That produced a much anticipated family outing each year.

In 1962, Justice Rabin was elevated to the Appellate Division, Second Department, which sat in Brooklyn. The Court was much smaller then, with only seven justices, and they took their lunch together every day, just before sitting for the afternoon arguments. Judge Rabin confided to his family that the judges took pride in having their decisions affirmed on appeal. If a judge’s decision was reversed, he had to contribute to a pool, and at the end of the year the proceeds of the pool were used for a gala lunch. Judge Rabin never revealed the amount he had to contribute.

In 1971, Governor Rockefeller appointed Rabin Presiding Justice of the Second Department. Justice Rabin viewed this as a pinnacle of his career. He immersed himself in the administrative side of the position. In a profile in the New York Post,5 the new P.J. stated that “this is by far the busiest appellate court in the state,” and he outlined his plans to eliminate the obstacles to moving cases along quickly. Justice Rabin continued to carry his share of hearing cases and writing opinions while he served as Presiding Justice. He referred to the briefs and papers he took home for evening reading as his “blue paperbacks.”

A year later, the New York Times did a profile on the two Presiding Justices of the Appellate Divisions that cover the downstate area, Justice Rabin in the Second Department, and Justice Harold Stevens in the First Department. The article, by Lesley Oelsner, begins:

Like the judges in old movies, Harold A. Stevens and Samuel Rabin have silvery hair and courtly manners and occupy ornate wood-paneled chambers. Aides speak to them in hushed voices, and about them in reverent phrases. Lawyers address them politely and even obsequiously.6

In 1981, Governor Malcolm Wilson appointed Justice Rabin to the Court of Appeals, along with Justice Harold Stevens. Both appointments were for one year, until elections for a full term could be held the following year. The Governor’s appointments were widely praised as a nonpartisan choice of two excellent judges. Both Judges were the Presiding Justices of the two Appellate Divisions that cover downstate, one was a Republican, the other a Democrat, one was Jewish, the other African-American.

At the time, judges of the Court of Appeals were required to run for election for full terms. Both seats would be up for election the following year. In an effort to reach a bipartisan agreement, the Republican party offered to endorse Judge Stevens, in exchange for the Democrats’ endorsement of Judge Rabin7. But the Democrats, foreseeing a victory at the polls, decided not to endorse a Republican. An editorial in the Long Island Daily Press criticized the Democrats for not endorsing Judge Rabin, and said, prophetically, “we hope to see the day soon when the selection of judges can be removed from partisan politics.”8 The New York Times took a similar editorial position.9

Judge Rabin, who was then 69 years old, would have been eligible to serve only one additional year on the Court. He decided against running for office, preferring to spend his energies on his judicial work that year than devote time to an election campaign that would give him only one more year on the Court.10

When Judge Rabin ascended to the Court of Appeals in 1974, he was one of five Judges who joined the Court in a period of two years. In addition, the Court had a new Chief Judge, Charles Breitel. The New York Times reported that this “most drastic change in personnel in its 128-year history,”11 produced “uncommon anxiety” among court-watchers. Judge Sol Wachtler, then a relatively new Associate Justice himself said, “The court is so new it has no track record.”12 One observer, who regularly appeared before the Court, said that Judges Rabin and Stevens “will be the swing men on criminal and civil liberties issues.”13

During his year on the State’s highest Court, Samuel Rabin authored some 25 opinions, covering a wide range of issues. His writings covered such topics as the constitutionality of a statute that barred a retiree from rejoining the pension system when he was reemployed after retirement, the interpretation of a will, the powers of the State Tax commission, the right under the Warsaw Convention to recover damages for psychic trauma suffered during the highjacking of a plane by a Palestinian organization, and the power of New York City to regulate retail prices of cigarettes.14 Many of Judge Rabin’s opinions were in the field of constitutional and criminal law, and, given their balance, they probably allayed the concerns of any criminal lawyer or prosecuting attorney.

Two cases especially commanded his attention. One, J. P. Stevens & Co. v. Rytex Corp., (34 N.Y. 2d 123 [1973]), involved the failure of an arbitrator to disclose to the parties a prior affiliation. The opinion is a scholarly compendium of the existing law on arbitral disclosure. Judge Rabin concluded that the “delicate question of disqualification” must be decided by the parties themselves, even if the court didn’t think the item of disclosure was important. That required the arbitrator to disclose everything possibly relevant, and to leave it to the parties to decide whether the disclosure mandated disqualification. Judge Rabin thought that the need for a broad disclosure requirement outweighed the possibility that a disgruntled party might seize upon a failure to disclose a minor point in order to overturn an award. The current trend in arbitration follows Judge Rabin’s views. The other opinion, Holodook v. Spencer, (36 N.Y. 2d 35 [1974]), narrowed a parent’s legal duty to supervise his or her child in cases where the child or a third party sought recovery for the child’s negligence. Judge Rabin’s opinion supported “the wide range of discretion a parent ought to have in permitting his child to undertake responsibility and gain independence,” (Id. at 50.) Judge Rabin followed this philosophy in raising his own children, as the writer of this note will attest.

Judge Rabin’s opinions were concise and readable, and, for the most part, spoke for a unanimous court. He usually began with a story about the people involved, reflective of the Judge’s philosophy that the law is about people. Viewed today, Judge Rabin would not fall within the camp of the strict textualists of statutory interpretation. For example, in Van Teslaar v. Levine (35 N.Y. 311 at 315 [1974]), a decision interpreting the conditions of eligibility under the State’s unemployment statutes, Judge Rabin wrote “in interpreting a legislative enactment of broad social policy such as unemployment insurance, the nuances of grammar and the maxims of statutory construction must yield to overall legislative policy.”

Judge Rabin probably had no idea at the time that one of his opinions, Freund v. Washington Square Press, Inc., 34 N.Y. 379 (1974), on a narrow point of damages for breach of a contract to publish a scholarly book, would make its way into a leading casebook on contract law.15 Perhaps the explanation is that the Judge had fortuitously cited one of the casebook author’s leading works in his opinion. The opinion overturned a $10,000 damages award and instead gave the disgruntled author nominal damages of six cents. By sheer coincidence, it turned out that Judge Rabin, by then retired from the bench, attended a contracts class with his wife Florence, taught by their son at Syracuse University College of Law on the day that case was discussed. While the students agreed that the reasoning of the case was unassailable, the Judge could not give any explanation to the class for the figure of six cents.

Upon retirement from the Court of Appeals, Judge Rabin went back to the Appellate Division, where he served as an Associate Justice for another seven years. When he retired from the bench, he became Of Counsel with Herzfeld and Rubin, a Manhattan law firm.

Judge Rabin was active in charitable work all his life. He was a founder of Long Island Jewish Hospital, in Queens. In the New York Post profile16 he observed that his son was born in Mary Immaculate Hospital in Queens, and that there was a need for another hospital, and “a need for the Jewish community to contribute.” He served on the Board of Trustees of Long Island Jewish Hospital, and as Chair, and was active in its governance. He died on May 7, 1993, and is buried at Montefiore Cemetery, in Queens.

Judge Rabin was an elegant and well-mannered man, always impeccably dressed. He was an avid golfer, playing regularly until just three weeks before his death. The judge enjoyed his family life. The family has fond memories of “Poppy” playing aggressive games of touch football with his grandsons in the street in his good leather shoes, and canoeing in the Adirondacks on family vacations.

Progeny

Judge Rabin married Florence Mittlemann on February 11, 1938. She survived him, and lives in Floral Park, Queens. They had two children, Robert J., a lawyer and later a law professor at Syracuse Law School, and Jane Stern, an author. Judge Rabin was survived by two grandsons, Benjamin Rabin, who continued the family tradition by becoming a lawyer, now practicing in Syracuse, N.Y., and William, a construction project manager. The genealogy continues with three great grandchildren, Alexandria Thomas, Samuel Rabin, and Benjamin Rabin.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Endnotes

- New York Post, January 18, 1971.

- Undated article in Long Island Daily Press, on file with Robert Rabin, Samuel Rabin’s son.

- See “City Rent Affairs Stir Assemblyman”, New York Times, November 26, 1848, p. 47.

- See “Albany Gets Bill on Baby Adoption”, New York Times, February 23, 1949, p. 21.

- New York Post, January 18, 1971.

- New York Times, April 8, 1972, p. 25.

- “G.O.P. Leader Bids Democrats Endorse 2 for Appeals Court”, New York Times, June 5, 1974, p. 20.

- Undated editorial in Long Island Daily Press, on file with author of this biography.

- Editorial, “Appeals Court Race”, New York Times, June 28, 1974, p. 32.

- “Rabin Drops Out of Appeals Court Race”, New York Times, June 29, 1974, p. 19.

- New York Times, January 18, 1974, p. 29.

- Ibid.

- Id. at p. 53.

- Respectively, Donner v. NYC Employees’ Retirement System, 33 N.Y. 2d 413 (1974), In re: Nurse’s Estate, 35 N.Y. 2d 381 (1974), Parsons v. State Tax Comm., 34 N.Y. 2d 190 (1974), Rosman v. TWA, 34 N.Y. 2d 385 (1974 ), and People v. Cook, 34 N.Y. 2d 100 (1974 ).

- The Freund case is found in Kessler, Gilmore and Kronman, Contracts, Cases and Materials, Third Ed., 1113 (Little, Brown, 1986). The Kessler casebook notes and extracts “the celebrated Fuller & Purdue article cited by Judge Rabin,” Kessler, Gilmore and Kronman, P. 1116. The author of this biography recalls that he taught the case from an edition of Fuller and Eisenberg, Basic Contract Law, which appeared in the 1980s.

- NY Post, January 18, 1974, supra n. 5.