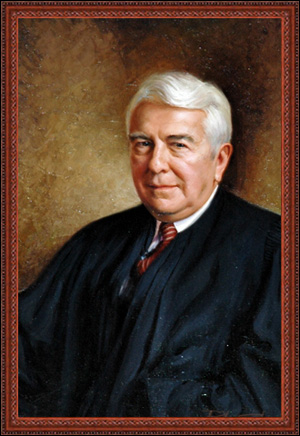

Judge Matthew J. Jasen served as an associate judge of the New York State Court of Appeals for eighteen years. A tireless advocate for the weaker members of society, Judge Jasen was a strong voice on the Court of Appeals while authoring more than 429 majority and 284 dissenting opinions. His legacy is one of well-reasoned, common sense jurisprudence that embodies both his deep-seated respect for stare decisis and his genuine concern for basic human rights. “Judge Jasen’s writings represent the unpretentious espousal of the American ideals that he . . . has come to cherish and protect . . . His is the heart and speech of a humanist who exalts our liberties and wants to see them intact.”1

Early Years

The son of Polish immigrants who fled Russian-occupied Poland at the turn of the twentieth century to seek freedom and opportunity in America, Matthew Joseph Jasen was born on December 13, 1915, in Buffalo, New York. At an early age, his parents, Joseph and Celine, instilled in him a belief in the hope and promise of the American way of life. His father, a tailor by trade, was the broker of that faith who made clear that his son Matthew was destined for great things.

Judge Jasen was educated in Buffalo, New York. He attended elementary school at Public School No. 24 and served as an altar boy at Transfiguration Church. He attended East High School from 1928 through 1932, where he ran cross-country, excelled on the tennis team and worked in the library to help pay expenses. He graduated from Canisius College in 1936, and has been recognized as one of its most distinguished alumni. He attended the (University at) Buffalo Law School from 1936 to 1939, where he also received the school’s distinguished alumnus award.2 Throughout law school, Judge Jasen worked as a postal clerk to help his family make ends meet during the Great Depression.

Judge Jasen was admitted to the New York State Bar in 1940 and entered private practice shortly thereafter, opening an office in his parents’ home.

World War II

Judge Jasen enlisted in the Army in 1943 where he was recommended by his commanders after basic training for Officer Training School and, on September 30, 1943, was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the artillery. Following his commissioning, he married the former Anastasia (“Nettie”) Gawinski on October 4, 1943.3 Shortly thereafter, he was selected to be a Military Government Officer and attended Harvard University, Civil Affairs School.

Judge Jasen served with courage and distinction as a Military Government Officer with the Seventh Army in Europe for three years, and participated in three major campaigns. One of the more memorable moments of his service – the liberation of French prisoners of war from a German internment camp – was captured by a British photographer and published in Life magazine.

Following the war, he served as President of the United States Security Review Board for the State of Baden-Württenberg, Germany. Then, in 1946, Judge Jasen was appointed by General Lucius D. Clay, Military Governor of Germany, as a judge in the newly established United States Military Government Court at Heidelberg, Germany. This post gave Judge Jasen civil and criminal jurisdiction over all persons in the American occupied zone of Germany not subject to military law. At only thirty-one years of age, he was the youngest judge serving in military government in Germany.

Judge Jasen’s experiences as a military judge exposed him to the horror of the Holocaust and the evil that a corrupt government can inflict upon its citizens by manipulating the law. That experience shaped his view of the world and galvanized his commitment to apply the rule of law fairly and impartially. As Judge Jasen related during his retirement ceremony,

Never in the history of mankind were so many innocent men, women and children singled out for persecution and destruction by one man and his followers. This spectacle of human evil unleashed upon the world was officially sanctioned by the Nazi government – and the courts of that country enforced this reign of terror . . . I was shocked to learn that the judicial branch of that government acquiesced in this spectacle of human evil.

Recognizing the moral consequences of judicial action, as well as inaction and silence, I resolved, then and there, to do my part to insure that our judiciary remained strong, and dedicated to government in accordance with the rule of law and not man. It is fidelity to the rule of law which has served, for 28 years, as the foundation of my judicial faith.4

Another highlight of Judge Jasen’s service in Germany was his chance to make the acquaintance of United States Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, who was serving as chief prosecutor during the Nuremberg trials. A fellow Western New Yorker, Justice Jackson took an interest in young Judge Jasen’s accomplishments as a military judge and invited him to visit in Nuremberg. Judge Jasen jumped at the opportunity. During their meeting, the two discussed, among other things, the political climate in Western New York and Judge Jasen’s aspiration to become a New York State Supreme Court justice. To this day, Judge Jasen fondly recalls their meeting and the effect it had on his commitment to ascend to the bench in New York.

Private Practice and Ascent to the Bench

In the Fall of 1948, Judge Jasen resigned his position as United States Military Government Court Judge and returned to private practice in Buffalo, where he quickly developed a reputation as one of Buffalo’s leading trial attorneys. He remained in private practice from December 1948 until November 1957, when Governor W. Averell Harriman appointed him to the New York State Supreme Court. He was elected to a full term the following year, becoming the first Democrat in modern history elected to the Supreme Court in the Eighth Judicial District. During his ten years on the Supreme Court, Judge Jasen authored 103 published opinions. “He was a well-regarded trial justice who treated lawyers and their clients with thoughtfulness and respect.”5 A staunch advocate of the prompt resolution of cases before him, he strove to “innovate and modernize calendar procedures to expedite trials and reduce clogged calendars.”6

Court of Appeals

Judge Jasen was elected to the New York Court of Appeals in 1967. As a testament to the high regard in which he was held, the State’s four major political parties endorsed him, along with Judge Charles D. Breitel, for the two vacancies on the Court, sparing both men the rigors of a statewide campaign. Sworn in on January 1, 1968, Judge Jasen replaced the Hon. John Van Voorhis.

Judge Jasen’s eighteen year tenure on the Court was marked “by high industry and impeccable integrity.”7 Never one to shy from a challenge, Judge Jasen embraced the tremendous volume of work at the Court and became an extraordinarily productive member. As one of his clerks later recalled, “Judge Jasen brought energy, independence, and integrity to his Court of Appeals service. Year in and year out, he would be a leader, and often the leader, in number of opinions authored.”8

Judge Jasen’s opinions, whether for the majority or in dissent, are regarded as “models of clarity, scholarship and independence of thought.”9 His signature technique for achieving clear and concise expression was to identify the key issues and their resolutions in the first paragraph of each opinion. In this way, the reader was able to “grasp at a glance the significance of the case.”10 “His opinions for the court stressed the precise issue decided, identified precedent that was not affected by the decision, and warned the reader as to issues not reached by the court.”11

Given the length of his tenure on the Court, it comes as no surprise that Judge Jasen’s opinions run the gamut of New York law. His majority writings include such important issues as: whether polygraph test evidence is admissible against a defendant in a criminal case;12 whether the same attorney can effectively represent criminal co-defendants;13 whether New York recognizes a cause of action for “wrongful life” brought by the parents of an abnormal infant;14 the threshold for “serious injury” within the meaning of New York’s No-Fault Insurance Law;15 whether an adult male can adopt his homosexual partner;16 the constitutionality of New York’s requirement that certain Judges of the State retire at age 70;17 whether the parents of a healthy but unwanted child can recover damages in a medical malpractice action for an unsuccessful abortion;18 and the extent of an accountant’s liability to non-clients.19 These are only a small sampling of the myriad important decisions Judge Jasen authored and his impact on the Court and New York law.

In addition to the many esteemed opinions Judge Jasen wrote for the Court, he was not timid about respectfully dissenting from the majority when he felt it necessary. For this reason, Judge Jasen has been widely known for his dissents. Although this might suggest frequent dissent, statistics show otherwise.20 In fact, he dissented no more frequently than other members of the Court. What made Judge Jasen’s dissents notable, was the passion and clarity with which he stated his opposing position. As one of his former colleagues on the Court related,

Judge Jasen . . . was consistently articulate and forceful in his writings. Perhaps more than any other judge on the court, he was reluctant, if he differed with the majority, to let his difference pass unwritten. His views were strongly stated in terms of deeply held principle, both of legal theory and of societal values. He regularly lifted up what he perceived to be the controlling principle and obliged the other members of the court to confront and publicly address his concern.21

In this regard, Judge Jasen’s dissenting opinions, like his majority writings, have been praised for their quality, courage, and persuasive effect. They have been and remain important instruments for change and stand as reminders of Judge Jasen’s vision, intellect, and the utility of dissenting opinions generally.

Of the dissenting opinions Judge Jasen authored, some of the most notable include: Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co.,22 in which he argued in favor of adjacent property owners’ rights to enjoin a cement factory from emitting pollutants; People v. Rogers,23 in which he dissented from the majority’s view that law enforcement officers could not question suspects represented by counsel in unrelated matters; Caprara v. Chrysler Corp.,24 in which he argued against the admission of evidence of post-accident design changes in product defect litigation; and Tebbutt v. Virostek,25 in which Judge Jasen wrote in support of a mother’s right to recover damages for pain and suffering after a doctor’s negligence caused the stillbirth of her child. Almost 20 years later, the Court of Appeals adopted Judge Jasen’s Tebbutt dissent when it overruled that decision in Broadnax v. Gonzalez.26

One of Judge Jasen’s more notable dissents was in People v. Ferber,27 in which he forcefully disagreed with the majority holding that New York’s criminal laws against child pornography were violative of the United States Constitution. Upon review, the United States Supreme Court reversed in a unanimous opinion based largely on Judge Jasen’s reasoning that the State’s interest in protecting children from sexual exploitation trumps a pornographer’s First Amendment right to produce sexually explicit materials depicting children.

He recorded another passionate dissent in People v. P.J. Video,28 involving the sufficiency of an affidavit supporting a search warrant authorizing the seizure of obscene materials. The majority held that the information submitted by police to establish probable cause was inadequate because there was a “higher standard” for evaluating a warrant to seize books and films. As the lone dissenter, Judge Jasen argued that the issue was not “whether the defendants are guilty beyond a reasonable doubt . . . but rather, simply whether the magistrate, in issuing the warrant to seize the movies, had probable cause to believe that they were obscene.”29 He emphasized the thorough description of both the graphic content and character of the films contained in the police affidavits. So convinced was Judge Jasen of the correctness of his position, he annexed as an appendix to the dissent, over the firm opposition of the majority, copies of those affidavits.

The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari and reversed in a 6-3 decision.30 Like Judge Jasen, the Court rejected the idea of a “higher standard” and applied the general probable cause standard of review to the affidavits presented in support of the warrant application. The Court held that it is “clear beyond peradventure that the warrant was supported by probable cause.”31

Quoting a substantial portion of Judge Jasen’s dissenting opinion,32 the Court said: “We believe that the analysis and conclusion expressed by [Judge Jasen] are completely consistent with our statement in Gates that ‘probable cause requires only a probability or substantial chance of criminal activity, not an actual showing of such activity.'”33 As an interesting historical irony, the Supreme Court too attached the supporting affidavits to its opinion. While it is often difficult to assess the impact of a dissenting opinion, there can be little doubt that Judge Jasen’s dissent in People v. P.J. Video carried significant influence with the Supreme Court majority.

After the Court

Upon reaching the mandatory retirement age of 70, Judge Jasen retired from the Court of Appeals on December 31, 1985, a victim of one of his last majority opinions which he authored in 1984 when he was 69 years old. That opinion, Maresca v. Cuomo,34 illustrated his unbending commitment to the rule of law over his own personal interests. Judge Jasen carried a 6-0 majority that upheld the constitutionality of the mandatory retirement age of 70 and, by doing so, insured his own departure from his beloved Court of Appeals the next year.

“Retirement,” however, is something of a misnomer in Judge Jasen’s case, as he continues today to be active in the legal community- locally, statewide, and nationally. Among his many post-retirement pursuits, Judge Jasen was appointed as a Special Master by the United States Supreme Court in the cases of South Carolina v. Baker,35 and Illinois v. Kentucky.36 He also served, on numerous occasions, as a Referee for the New York State Commission on Judicial Conduct, spearheading investigations into alleged judicial improprieties and making recommendations for disposition to the Commission.

Judge Jasen also returned to private practice with the Buffalo law firm of Moot & Sprague in 1986. When that firm dissolved in 1989, he served as Of Counsel to Jasen & Jasen, P.C., where he practiced with his sons Mark and Peter. Until his death on February 4, 2006,37 at age 90, he had been spending a full eight hours at the office, five days a week, taking only a few weeks each year to vacation in Florida.

Progeny

Judge Jasen has four children – Mark M. Jasen, Peter M. Jasen, Carol (Jasen) Sampson, and Christine (Jasen) MacLeod – and numerous grandchildren. His sons Mark and Peter are both practicing attorneys in Buffalo, and his grandson Daniel Jasen was recently admitted to practice law in New York.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Reflections of Two Law Clerks, 48 Syr. L. Rev. 1487 (1998), comments by Robert C. (Chuck) Zundel.

Remarks on Retirement of Judge Jasen, 66 N.Y.2d vii, ix (1985).

Wachtler, et al., A Tribute to Judge Matthew J. Jasen, 35 Buff. L. Rev. 1-38 (1986).

Published Writings Include:

Recalling the Holocaust, Bureau of Curriculum Development, New York State Dept of Educ., Teaching About the Holocaust and Genocide (1985).

Introduction, 30 Buff. L. Rev. 1 (1981).

An Elected Judge Favors Merit Selection, NYLJ, October 28, 1977, at 1, col. 4.

Obiter Dicta, Remarks to Newly Admitted Lawyers, 48 NY St BJ 231 (Apr. 1976).

Tribute to Justice Heflin, 7 Cumb L Rev 386 (Fall 1976).

The Lawyer’s Bookshelf, Review: Zusman and Carnahan, Mental Health: New York Law and Practice, NYLJ, November 14, 1975, at 2, col 2.

A Judge Looks at the Contributory Negligence Rule, 36 NY St BJ 393 (Oct. 1964).

Endnotes

- Rosenblatt, et al, A Tribute to Judge Matthew J. Jasen, 35 Buff L Rev 1, 13 (1986) (“Tribute”).

- Today, the University at Buffalo Law School annually recognizes Judge Jasen’s legacy by awarding the Judge Matthew J. Jasen Appellate Practice Award for outstanding achievement in appellate advocacy to one of its graduating students.

- Judge Jasen was married to Nettie for almost 30 years, until she passed away in 1970. He subsequently married Gertrude (“Trudy”) Travers in 1972. Unfortunately, his second wife lost her battle with cancer only eight months after they married. Thereafter, in August 1973, Judge Jasen married Grace Frauenheim, with whom he also shared 30 years of marriage, until her death in 2003.

- Remarks on Retirement of Judge Jasen, 66 NY2d vii, ix (1985) (“Remarks”). Judge Jasen also recognized the importance of education in avoiding the horrors of genocide. In fact, he was a key contributor to a New York State Department of Education text concerning the holocaust and genocide.

- Scheinkman and Sheridan, Tribute, 35 Buff. L. Rev. at 15.

- Id.

- Id. at 14.

- Id. at 16.

- Remarks, 66 NY2d at vii.

- Scheinkman and Sheridan, Tribute, 35 Buff L Rev at 16.

- Id.

- People v. Leone, 25 NY2d 511 (1969).

- People v. Gomberg, 38 NY2d 307 (1975).

- Becker v. Schwartz, 46 NY2d 401 (1978).

- Licari v. Elliot, 57 NY2d 230 (1982).

- In re Robert Paul P., 63 NY2d 233 (1984).

- Maresca v. Cuomo, 64 NY2d 242 (1984). Regarding Maresca, two of the Judge’s former law clerks relate: “This case reached the Court on December 29, 1984, and had to be decided in two days time lest there be confusion and uncertainty over the terms of offices of the retired judges and their successors. The Judge’s opinion spanned over ten printed pages and referred to nearly fifty prior cases, legal treatises, and law review articles. In short, a masterful job, under severe time constraints.” See Scheinkman and Sheridan, Tribute, 35 Buff L Rev at 23. Ironically, and as a testament to his selflessness, Judge Jasen authored the opinion when he was himself 69 years old and on the cusp of mandatory retirement.

- O’Toole v. Greenberg, 64 NY2d 427 (1985).

- Credit Alliance Corp. v. Arthur Anderson & Co., 65 NY2d 536 (1985).

- Powers, Tribute, 35 Buff L Rev at 24.

- Jones, Tribute, 35 Buff L Rev at 7.

- 26 NY2d 219 (1970).

- 48 NY2d 167 (1979). Judge Jasen’s dissent in Rogers inspired a book entitled Outrage, which portrays a fictional crime and trial centered around the Rogers decision and, more particularly, Judge Jasen’s dissent. The book was adapted into a play that opened in Washington, D.C. in December 1982. It later became a made-for-television movie shown nationally in March 1986.

- 52 NY2d 114 (1981).

- 65 NY2d 931 (1985).

- 2 NY3d 148 (2004).

- 52 NY2d 674 (1981). Judge Jasen’s dissent in Ferber was vindicated by the Supreme Court’s subsequent 9-0 reversal in New York v. Ferber, 458 US 747 (1982).

- 65 NY2d 566 (1985).

- Id. at 573.

- 475 US 868 (1986).

- Id. at 876.

- Id. at 877.

- Id. at 877-78.

- 64 NY2d 242 (1984).

- 484 US 920 (1987). Judge Jasen’s subsequent request to be discharged as Special Master was granted in May, 1988. See South Carolina v. Baker, 486 US 1003 (1988).

- 487 US 1215 (1988).

- New York Law Journal, February 7, 2006; see also, Buffalo News, February 5, 2006; editorial on February 12, 2006.