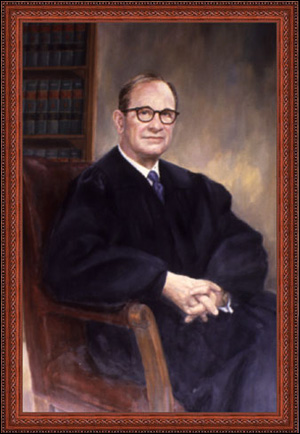

Charles Breitel, the 30th chief judge of the New York State Court of Appeals was a brilliant, complex, energetic, and quietly ambitious man whose modesty and rigorous standards never allowed him to quite appreciate what a remarkable life he led. His was a wonderful American story: offspring of immigrant parents; a scholarship student at the finest educational institutions who learned his trade while enduring the harshest years of the Great Depression; a 64-year marriage that started with an elopement; a close relationship with Thomas Dewey that nearly led him to a seat on the Supreme Court of the United States; and almost 30 years as a judge—at nisi prius, the Appellate Division1, and finally, the Court of Appeals where he initiated and helped implement significant reforms that shaped our modern system of justice. Along the way, he served as husband, parent, teacher, counselor, and friend to legions who remember him with respect, occasional trepidation, and great affection.

Judge Breitel really did “love the law”; indeed, he once wrote that he “love[d] the court system,” not a commonly expressed view.2 He cared deeply for the Court of Appeals, which he unabashedly described as the “greatest Court in the nation . . . surpass[ing] the Supreme Court by far.”3 And, this was a man who knew his neighborhood. After all, he had participated at all levels of the New York legal system, from a clerk at a small law firm to the highest judicial office in the state. He had pride and affection in his city, the “greatest megalopolis of the western hemishere,”4 and his early immersion in that commercial cauldron laid the groundwork for many of the most sophisticated, yet practical “business” decisions ever issued by any court. Perhaps most of all, he reveled in the elegant interaction of the three branches of government, a structure that he believed actually works even if, from time to time, stalwart guardians such as himself had to take unpopular, even courageous, stands, to ensure that none of the three bodies overstepped its bounds. But, to truly understand this fascinating and significant man, we have to start at the beginning.

As a Youth

Judge Breitel’s mother and father, Herman and Regina Breitel, emigrated with their three daughters, from Lwow (now in Poland) to the United States in the early days of the 20th century. Judge Breitel was born in New York on December 12, 1908. Two years later, his father died.

A forceful woman (she obtained her driver’s license in 1907), Mrs. Breitel supported her four young children by selling hats at a Lower East Side store. Judge Breitel attended the Evander Childs High School in the Bronx and then went, on a scholarship, to the University of Michigan where he earned what money he could by working as tutor, and as a cashier in a movie theater.5 In his sophomore year, he met a costudent, Jeanne Hollander, and they dated for a week. They broke up, after a disagreement over a tie she had given him, but, six weeks later, they “made up” and eloped, marrying in Howell, Michigan, on April 9, 1927. He was 18; she was 19. Judge Breitel later explained he had married his wife for her “lecture notes.”

Both Breitels started at Michigan Law School; Jeanne graduated from there while the judge spent his last two years at Columbia Law School.6 The rigors of the Depression marred their early years together in New York City; indeed, his daughter, Eleanor, recalls the judge telling her that food was so scarce that, on one occasion, he actually fainted in the street from hunger. On his graduation from law school in 1933, Judge Breitel was able to secure a job as a clerk in a small firm, which, not long thereafter, failed.

As a Young Man

At the age of 26, Judge Breitel’s life took a decided turn for the better when he came to the attention of District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey. As is well known, during the 1930s, Dewey forged a reputation in New York City as the prototype “crusading District Attorney and gang-buster.” By his side, holding a succession of jobs with increasing responsibility, was the young Breitel, moving from the Special Rackets Investigation Bureau to assistant chief of the Indictment Bureau and then chief of that bureau. Along the way, protégés gathered and coalesced into a group known as “Dewey’s Dozen,” consisting of such eminent figures as (among others) Stanley Fuld, Whitman Knapp, Murray Gurfein, Frank Hogan, and, of course, Charles Breitel. Thurston Greene, alive and well at 99, is their last survivor.

As Charles Beeching, a former clerk for the judge, once observed, the 1930s were an era when “crusading law enforcement officers were public heroes, and the exclusionary rules of evidence . . . and the whole spectrum of constitutional guarantees of procedural rights were at least a generation away.”7 As the rules changed (e.g., Mapp and Miranda), Judge Breitel was faithful to their new commands; still, the legacy of those formative years as a “crime fighter” can be found in such observations by the judge, made 30 years later, as: “We may prate about acquitting nine guilty men rather than risk the conviction of one innocent but we in fact shudder at the idea of turning loose nine guilty men capable of committing crimes of violence and grave depredation.”8

During the brief period between the termination of his service as district attorney and election as governor of New York, Dewey demonstrated his regard for his young assistant’s abilities by joining him in the formation of their own law firm, Dewey & Breitel. When Dewey was elected governor, he named Judge Breitel as counsel who moved, with his family, to Albany. The Albany years gave Judge Breitel a breadth of understanding for, and appreciation of, the legislative process that played a significant role in shaping his judicial persona, including, perhaps, his reluctance to interfere unduly with mandates from popularly elected bodies.9

In any event, the trajectory of his career nearly veered to the South: It has been often assumed, quite accurately, that if Governor Dewey had been elected president in 1944 or 1948, Judge Breitel would have either become attorney general or a Supreme Court justice. But, the Democrats prevailed, and, in 1950, Governor Dewey appointed Judge Breitel to an interim term on the Supreme Court of New York, praising his appointee for possessing “the finest legal mind in the State.”10 While as a Republican he was defeated in his first bid for reelection, he was appointed to another interim term and then elected in 1951 for a 14-year term.

As a Husband and Father

Judge Breitel had a warm, full family life. He often said, cheerfully, that he had been surrounded by women all of his life (his mother, three sisters, his wife, and two daughters). His daughter, Eleanor Alter,11 has become a prominent divorce lawyer, while Vivian Breitel has pursued varied and productive careers in finance and fine arts. Not surprisingly, Judge Breitel was a demanding parent: He even edited letters sent to him by his children. But he was by no means a bookish martinet; he loved baseball games, movies, and taking pictures of his family, which he developed in his own darkroom. He seldom missed a good parade and, during World War II, kept a victory garden in Albany. An amateur carpenter, he even built a two-room doghouse for a cocker spaniel, given to the Breitels by Governor Dewey.

As for his marriage, the most startling, yet beguiling, aspect of his relationship with his wife, Jeanne, was how quickly they decided on a union that would last for 64 years. The main reason, of course, is that they were so much alike: They were both smart, sensitive, proud, blessed with a self-effacing wit, and fiercely loyal to each other. Both smoked—a lot. They even rolled their own cigarettes during the war. Perhaps in response to the rigors of the Depression, their lifestyle approached the frugal; they never took cabs, owned a television set, or went to restaurants. Instead, they played chess, read voraciously, raised their family, and supported each other in every way for a long and happy marriage.

Early Judicial Appointments

To return to the courts: In 1952 Governor Dewey appointed Judge Breitel to a seat on the Appellate Division, First Department, certainly one of the busiest appellate courts in America. This tribunal is charged with hearing appeals from almost every type of order issued by the Supreme Court, final or interlocutory, substantive or procedural. Consequently, in his 14 years of service on this bench, Judge Breitel heard appeals in cases encompassing any controversy that fell within the broad jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. The volume was so great that, even though the Appellate Division was a panel court, each judge could count on reviewing and deciding anywhere from 25 to 35 cases a month. It was during this time that Judge Breitel spearheaded the concept of a hot bench, which meant reading the briefs and records in every case considered by his panel before every argument. This process, which enlivened and often shortened the oral presentations, exponentially increased the workload of the judges, many of whom had to follow young Breitel’s lead, lest they seem less assiduous by comparison.

And it was a strong court, composed of jurists who may not have had household names but whose reputations shone in the experienced and discerning New York legal community: e.g., Cohn, Botein, Steuer, Eager, Dore, Peck, Rabin, and several others. Given their extremely busy workloads, these judges specialized in the speedy, often terse delivery of results, rather than in lengthy opinions, crafted in Holmesian prose.12

Quite apart from his judicial burdens, Judge Breitel was immersed in numerous legal “extracurricular activities.” During the decade of the 1960s, he served as an adjunct professor of law at Columbia, a member of the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice, the Federal Commission on International Rules of Judicial Procedure, and the American Law Institute Committee on the Model Penal Code. Certainly, his clerks helped to some extent on these assignments, but he alone performed the vast majority of the tasks, writing longhand, hour after hour, late into the night, on a series of yellow pads.

But, his major assignment was, of course, at 25th Street and Madison Avenue, where his work was dedicated mainly to resolving controversies and absorbing a prodigious amount of the substantive and procedural law of New York State. Thus, when Gov. Nelson Rockefeller called Judge Breitel late in the afternoon in November 1966 to offer him a seat on the New York State Court of Appeals, it is safe to say that the governor could not have selected a more qualified man.

The years in Albany started quietly: Stanley Fuld, Judge Breitel’s old colleague from the “Dewey Days,” was the chief judge and the new arrival tread softly, at least administratively, even though the “cold bench” procedures in Albany were not to his liking. Nevertheless, within two months of his arrival, Judge Breitel wrote the majority opinion, upholding the validity of a local ordinance banning all off-site billboards, a major goal of “aesthetic environmentalists.”13 Even as he neared an important milestone in his career, Judge Breitel agreed to author the majority opinion in a highly controversial case, Byrn v. New York City Health & Hospitals Corp.,14 which struck down a constitutional challenge to a law permitting abortion within 24 weeks from commencement of pregnancy. Judge Breitel met the core issue head on when he wrote, “unborn children have never been recognized as persons in the whole sense.”15 There were emotional dissents from Judges Burke and Scileppi, who claimed links between the law and principles espoused by Nazi Germany.16

As Chief Judge

In 1973, as the retirement of Chief Judge Fuld approached, the common expectation was that Judge Breitel would be nominated by both political parties, and elected, essentially unanimously, as the new chief. However, the Democratic Party, “anticipating a large turnout of their adherents in [the 1973] New York mayoral race, refused to abide by the 60-year-long precedent of cross-endorsing the senior associate [Court of Appeals judge]” as the new chief.17 A prominent negligence lawyer, Jacob Fuchsberg, secured the Democratic nomination by winning an extremely narrow primary over Judge Jack Weinstein of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York. Mr. Fuchsberg then went on to wage an aggressive and expensive campaign for chief judge, thereby forcing Judge Breitel into a contest that he found unseemly and demeaning. While he was proud of his record and confident that he was far more qualified for the position, Judge Breitel had no taste for self-aggrandizement, let alone the personal attacks often associated with elections.

Nevertheless, the judge was no shrinking violet and, of course, he wanted the job. Reluctantly then, he hit the hustings (to the extent a judge could), obtained the endorsement of the Republican and Liberal Parties, made speeches, debated, gave as good as he got, and eventually defeated Mr. Fuchsberg and Judge James Leff (the Conservative Party nominee who openly preferred Judge Breitel) by 300,000 votes.18

So, Charles Breitel was the chief, and while he only had four years until retirement to enjoy the job, he went to work with a will. The first order of business was to call upon the Socratic method, so familiar to law students and dear to the chief’s heart.

Thus, almost immediately after his election, the Court of Appeals became a “hot bench.” Emulating the Appellate Division system, the new chief decreed that each judge had to be fully prepared on all cases before the oral argument. As a result, spirited and informed interchanges between counsel and court sharpened the issues, often shortened the presentations, and usually stimulated meaningful discussions on the points that the court found most significant. Equally important, the judges’ familiarity with all the cases in an early stage of the appellate process helped expedite their resolution, diminishing materially the time between oral argument and decision.

On a broader front, the chief judge moved with equal dispatch. In 1974, he appointed Richard Bartlett as the first chief administrator of the state court system. Next, he vigorously supported constitutional amendments, passed shortly thereafter, which created the central administration of the New York courts, as well as the Commission on Judicial Conduct.

But, reaching a goal even more important to him—abolition of the election process he had been forced to endure—required the support and leadership of a most unlikely ally: Gov. Hugh Carey, a Democrat from Brooklyn. To achieve that end, a constitutional provision in force since 1846, requiring the election of Court of Appeals judges, had to be repealed and new legislation passed. Nevertheless, a quadrumvirate was formed: Governor Carey, his counsel, Judah Gribetz, Judge Bartlett, and, of course Chief Judge Breitel. Party divisions were surmounted, and the voters approved the required constitutional amendment in 1977, thanks, primarily, to a large favorable vote from New York City. Popular elections were replaced by gubernatorial nominations, selected from a list furnished by the Commission on Judicial Nomination, with the governor’s choice subject to approval by the State Senate.

One of the failings of the New York system, as opposed to the federal courts, is the arbitrary retirement age of 70. In the five years prior to 1978, Chief Judge Breitel authored a series of significant opinions on important issues that illuminate, in a perverse way, the wastefulness of losing a judge who was, in point of fact, probably in his “judicial prime.”

Significant Court of Appeals Opinions

In any event, as the chief is said to have told his wife, “his opinions were his biography.”19 If so, 1975 to 1978 was a truly busy period, as the court was confronted with a series of major controversies that required judicial resolution:

- During the depths of New York City’s fiscal crisis, the legislature enacted a three-year moratorium to stay actions brought to enforce payment of the city’s short-term obligations. The court held that the law violated the full faith and credit provision of the New York Constitution. As the chief judge wrote: “But it is a Constitution that is being interpreted and as a Constitution it would serve little of its purpose if all that it promised, like the elegantly phrased Constitutions of some totalitarian or dictatorial Nations, was an ideal to be worshipped when not needed and debased when crucial.”20

- The court, per Chief Judge Breitel, upheld the Rockefeller drug laws against an Eighth Amendment challenge.21

- In a decision that pitted the principles of private property rights and legislative deference against each other, the court (per the chief judge) ruled against the owners of the Grand Central Terminal who sought to overturn the city’s landmark preservation regulation prohibiting construction of an office building on top of the terminal.22

- Finally, the court upheld a constitutional challenge to New York’s death penalty. Writing for the dissent that contended that the legislature had acted within the constitutional bounds, Chief Judge Breitel included this revealing footnote in his opinion:

Speaking for myself alone among the dissenters I find capital punishment repulsive, unproven to be an effective deterrent (of which the [instant] case itself is illustrative), unworthy of a civilized society (except perhaps for deserters in time of war) because of the occasion of mistakes and changes in social values as to what are mitigating circumstances, and the brutalizing of all those who participate directly or indirectly in its infliction.”23

While those who have sought to capsulize Charles Breitel’s judicial philosophy often fasten on the “conservative” label, the foregoing examples demonstrate that no such pat generalization can validly be made. And, in language as relevant as today’s headlines, the Judge himself dismissed such attempts as mischievous:

It is customary these days, to a tiresome degree, and most often fruitlessly, to classify judges categorically by conclusory and all too-encompassing labels: conservative–liberal–activist–restrained, pro-this–anti-that and the like. The stretching for facile labels to achieve the nomenclature but not necessarily the substance of analysis is an obvious temptation. Often a flight from thinking, it results inevitably in oversimplification and superficiality. Most judges, indeed most people, do not classify so simply. Certainly, that should be true of persons engaged in an analytical profession in a very complicated world, and all the more of those who serve in judicial roles.24

Pursuant to the inflexible statutory command, the judge’s 44 years of active public service ended on December 20, 1978. For 13 years thereafter, he resigned himself to a far quieter, yet still productive, phase of his life, practicing law at Proskauer Rose, serving as an expert witness, writing, lecturing, and enjoying time with his family. Upon his death on December 1, 1991, eulogists extolled his manifold contributions to law and society; since then, it is fair to say that his stature among the great jurists of the 20th century places him at or near the top.

While these professional encomia would have pleased the judge, they would not have come as a complete shock. What would have surprised him was the warmth and sincerity of the expressions of affection he engendered from those who knew him best. After all, this was a man who had declared at his retirement: “I know that I am not an easy man to live with. . . . I have to struggle with my character. . . . I have a temper that sometimes rages uncontrolled.”25 Nevertheless, his colleagues, among many others, registered firm dissents and spoke warmly and publicly about his depth of character and generosity of spirit. No one said it better than one of his most beloved mentors: Judge Joseph W. Bellacosa:

I would like to share with your readers, our professional colleagues, a personal characteristic not well known about Judge Breitel—his sage sensitivity. He shielded his compassionate and caring side from the world, so few were privileged to see behind his stern exterior, hardened by the Depression, by the demanding responsibilities of high public service over five decades and by the jurisprudence of realism which he espoused. . . . The Official New York Reports are a permanent testament to his greatness as a judge. My grateful heart, however, will correspondingly bear witness for all time to the memory of a sweet and good person.26

Progeny

On Apr. 9, 1927, Judge Breitel married Jeanne Hollander, with whom he had three children, Eleanor (1938- ), Vivian (1945- ), and Sharon, who died in infancy. Judge Breitel passed away in 1991, and his wife died four years later.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Beeching, Charles D. Breitel—Self-Conscious Jurisprudence, 29 Syracuse L. Rev. 1, 6 (1978).

Bellacosa, A Remembrance: Chief Judge Breitel, N.Y.L.J., Dec. 12, 1991, at 2.

Berger and Zundel, Reflections of Two Clerks, New York State Court of Appeals.

Bierman, Preserving Power in Picking Judges: Merit Selection for the New York Court of Appeals, 60 Alb. L. Rev. 339, 345 (1996).

Breitel, The Lawyer as Fiduciary, Address to the Am. Bar Assn, (May 31, 1975), in 31 Bus. Law. 3, 1975-76, at 3.

Breitel, Criminal Law and Equal Justice, Sixth Annual William H. Leary Lecture (Apr. 19, 1966), in 1966 Utah L. Rev. 1, 11 (1966).

Breitel, The Lawmakers, 22nd Annual Benjamin N. Cardozo Lecture Before the Association of the Bar of the City of New York (Mar. 23, 1965), in 65 Colum. L. Rev. 749, 777 (1965).

Breitel, A Tribute to Judge Matthew J. Jasen, 35 Buffalo Law Rev. 5 (1986).

Conversations with Eleanor Alter, Vivian Breitel, Richard Zabel, and former colleagues of Judge Breitel.

Fried, Chief Judge Breitel and Judicial Legislation, 45 Brook. L. Rev. 231 (1979).

Mayo, Charles D. Breitel—Judging in the Grand Style, 47 Fordham L. Rev. 5 (1978).

McLaughlin, Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel, 47 Fordham L. Rev. 1 (1978); Wachtler, supra.

Owen Philip, Cynthia, Paul Njelski, Where Do Judges Come From? (Institute of Judicial Administration, 1999).

Pace, Charles D. Breitel, Chief Appeals Judge in the 1970’s, N.Y. Times, Dec. 3, 1991, at B12.

Remarks of Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel, Ceremony Marking Retirement of Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel (Dec. 20, 1978), in 45 N.Y.2d vii, xi.

Remarks of Chief Judge Sol Wachtler, Memorial for Former Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel (Jan. 7, 1992), in 78 N.Y.2d vii, vii.

Remarks of Judge Matthew J. Jasen, Ceremony Marking Retirement of Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel (Dec. 20, 1978), in 45 N.Y.2d vii.

There Shall Be a Court of Appeals, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York, (1997) (booklet on file with the Court).

Published Writings

A Tribute to Judge Matthew J. Jasen, 35 Buff. L. Rev. 1 (1986).

Tribute to Shirley M. Hufstedler, 1982 Ann. Surv. Am. L. xxiii (1982).

A Tribute to Adolf Homburger, 1 Pace L. Rev. 7 (1980).

Foreword to Historic Courthouses of New York State, by Herbert Alan Johnson and Ralph K. Andrist, Columbia University Press, New York (1977).

Adrian P. Burke, 48 St. John’s L. Rev. 435 (1974).

Chief Judge Stanley H. Fuld, 25 Syracuse L. Rev. 1 (1974).

Llewellyn: Realist and Rationalist, 18 Rutgers L. Rev. 745 (1964).

Controls in Criminal Law Enforcement, Speech at the Third Dedicatory Conference on Criminal Law (Jan. 1960), in 27 U. Chi. L. Rev. 427 (1960); Breitel, supra 7; Breitel, supra 4.

The Quandary in Litigation, Earl F. Nelson Memorial Lecture (Mar. 4, 1960), in 25 Mo. L. Rev. 225 (1960).

A Commentary on the Legislative Process, 1, Syracuse L. Rev. 59 (1949-50).

Endnotes

- Judge Charles Breitel was associate justice of the Appellate Division, First Department.

- Remarks of Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel, Ceremony Marking Retirement of Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel (Dec. 20, 1978), in 45 N.Y.2d vii, xi.

- Id. at ix.

- Penn Cent. Transp. Co. v City of New York, 42 N.Y.2d 324, 331 (1976).

- The author is most grateful to Eleanor Alter and Vivian Breitel, the daughters of Judge Breitel, who were the sources for most of the vignettes from the nonpublic life of their father.

- As he later revealed, his “ambition was to become a corporate or a banking lawyer. [But] I got out of law school in 1932. That was the end of that ambition.” Charles D. Breitel, The Lawyer as Fiduciary, Address to the Am. Bar Assn. (May 31, 1975), in 31 Bus. Law. 3, 1975-76, at 3.

- Charles T. Beeching Jr., Charles D. Breitel—Self-Conscious Jurisprudence, 29 Syracuse L. Rev. 1, 6 (1978).

- Charles D. Breitel, Criminal Law and Equal Justice, Sixth Annual William H. Leary Lecture (Apr. 19, 1966), in 1966 Utah L. Rev. 1, 11 (1966).

- His most celebrated iteration of this philosophy may be found in the concluding sentence of his 1965 Benjamin N. Cardozo Lecture: “The power of the courts is great indeed, but it is not a power to be confused with evangelic illusions of legislative or political primacy. If this is true, then self-restraint by the courts in lawmaking must be their greatest contribution to the democratic society.” Charles D. Breitel, The Lawmakers, 22d Annual Benjamin N. Cardozo Lecture Before the Association of the Bar of the City of New York (Mar. 23, 1965), in 65 Colum. L. Rev. 749, 777 (1965). Judge Breitel was also a prolific writer. For other examples of his published work, see Charles D. Breitel, Adrian P. Burke, 48 St. John’s L. Rev. 435 (1974); Charles D. Breitel, Chief Judge Stanley H. Fuld, 25 Syracuse L. Rev. 1 (1974); Charles D. Breitel, A Commentary on the Legislative Process, 1. Syracuse L. Rev. 59 (1949-50); Charles D. Breitel, Controls in Criminal Law Enforcement, Speech at the Third Dedicatory Conference on Criminal Law (Jan. 1960), in 27 U. Chi. L. Rev. 427 (1960); Breitel, supra 7; Breitel, supra 4; Charles D. Breitel, Llewellyn: Realist and Rationalist, 18 Rutgers L. Rev. 745 (1964); Charles D. Breitel, The Quandary in Litigation, Earl F. Nelson Memorial Lecture (Mar. 4, 1960), in 25 Mo. L. Rev. 225 (1960); Charles D. Breitel, A Tribute to Judge Matthew J. Jasen, 35 Buff. L. Rev. 1 (1986); Charles D. Breitel, A Tribute to Adolf Homburger, 1 Pace L. Rev. 7 (1980); Charles D. Breitel, Tribute to Shirley M. Hufstedler, 1982 Ann. Surv. Am. L. xxiii (1982).

- Eric Pace, Charles D. Breitel, Chief Appeals Judge in the 1970’s, N.Y. Times, Dec. 3, 1991, at B12.

- Eleanor did, in fact, produce two grandsons to give the judge some male company: Richard Zabel (who served as an assistant United States attorney and is now a partner at Akin, Gump Strauss, Hauer & Feld); and David Zabel, who is the executive producer of the long-running television show “E.R.”

- Of course, there were exceptions. Notably, Judge Breitel authored the majority decision in Rockwell v. Morris, 211 N.Y.S.2d 25 (App. Div. 1961). Holding that New York City’s denial of a park permit to the prominent American Nazi George Rockwell amounted to a prior restraint, Judge Breitel warned: “So, the unpopularity of views, their shocking quality, their obnoxiousness, and even their alarming impact is not enough. Otherwise, the preacher of any strange doctrine could be stopped; the anti-racist himself could be suppressed, if he undertakes to speak in ‘restricted’ areas; and one who asks that public schools be open indiscriminately to all ethnic groups could be lawfully suppressed, if only he choose to speak where persuasion is needed most.” Id. at 35-36.

- Matter of Cromwell v. Ferrier, 19 N.Y.2d 263 (1967). In so doing, Judge Breitel convinced a majority of his new colleagues to overrule one of the court’s own decisions, a case that specifically forbade such restrictions, Matter of Mid-State Adv. Corp. v. Bond, 274 N.Y. 82 (1937).

- 31 N.Y.2d 194 (1972).

- Id. at 200.

- Id. at 211 (Burke, J., dissenting).

- Luke Bierman, Preserving Power in Picking Judges: Merit Selection for the New York Court of Appeals, 60 Alb. L. Rev. 339, 345 (1996).

- Cynthia Owen Philip, Paul Njelski, Where Do Judges Come From? (Institute of Judicial Administration, 1999).

- Remarks of Chief Judge Sol Wachtler, Memorial for Former Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel (Jan. 7, 1992), in 78 N.Y.2d vii, vii. This short biography does not presume to offer a scholarly analysis of Judge Breitel’s prodigious output during his service on the bench. For an in-depth treatment of various aspects of his work, authored by erudite commentators, see Beeching, supra 6; Bernard J. Fried, Chief Judge Breitel and Judicial Legislation, 45 Brook. L. Rev. 231 (1979); Remarks of Judge Matthew J. Jasen, Ceremony Marking Retirement of Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel (Dec. 20, 1978), in 45 N.Y.2d vii; Thomas W. Mayo, Charles D. Breitel—Judging in the Grand Style, 47 Fordham L. Rev. 5 (1978); Joseph M. McLaughlin, Chief Judge Charles D. Breitel, 47 Fordham L. Rev. 1 (1978); Wachtler, supra.

- Flushing Nat’l Bank v. Mun. Assistance Corp., 40 N.Y.2d 731, 739 (1976).

- People v. Broadie, 37 N.Y.2d 100 (1975).

- Penn Cent. Transp. Co. v. City of New York, 42 N.Y.2d 324 (1977).

- People v. Davis, 43 N.Y.2d 17, 39 n.1 (1977) (Breitel, C.J., dissenting).

- Charles D. Breitel. A Tribute to Judge Matthew J. Jasen, 35 Buffalo Law Rev. 5 (1986).

- Breitel, supra n. 1, at x.

- Joseph Bellacosa, A Remembrance: Chief Judge Breitel, N.Y.L.J., Dec. 12, 1991, at 2.